Featured

‘Woman Hold My Hand’

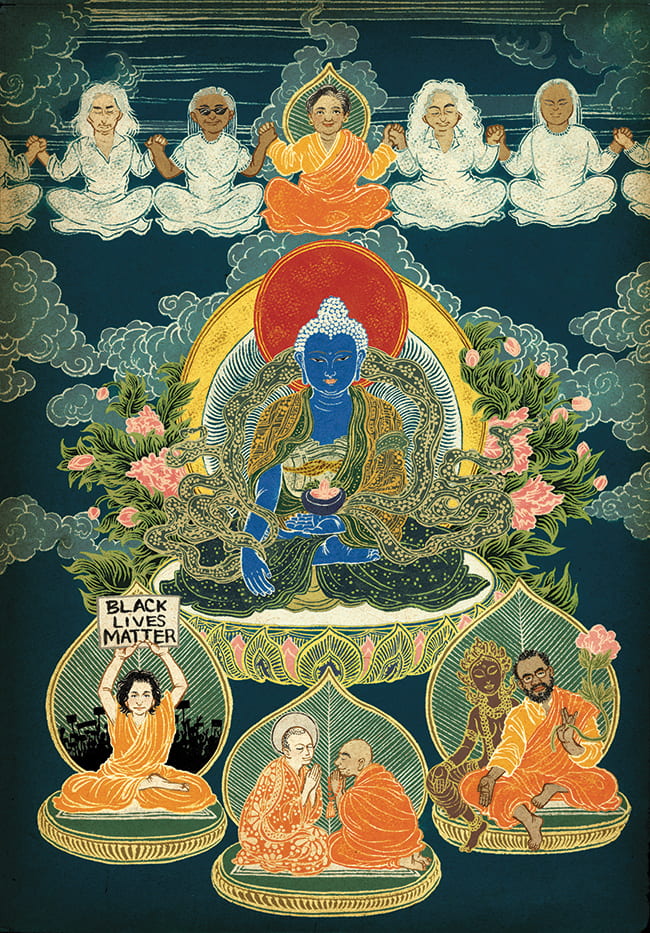

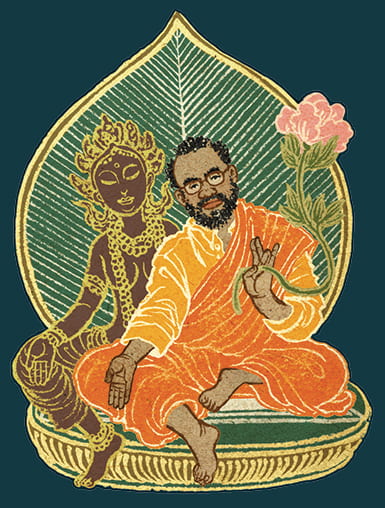

Visualizing Tara: swift one, mother, liberator, womanist.

Illustration by Yuko Shimizu

By Rod Owens

Who binds my wounds when I’m bruised and battered

By strangers and those daily walking in my life

Who lets me know that I’m more than my hurtings

Woman hold my hand

—“Mae Frances,” Bernice Johnson Reagon1

I had never heard of Sweet Honey in the Rock until I began doing some research on the history of black American roots music more than a decade ago as a writer and editor for a small arts and activism magazine. I wanted to chart the development of black roots music and place it within the tradition of black liberation struggle. Sweet Honey (as they are called in shorthand) and its founder, Bernice Johnson Reagon, came up often as a group that embodied the tradition of black roots music as an expression of social liberation. I was intrigued. I discovered that the group was celebrating its twenty-fifth anniversary during that time with the release of a new album. I decided to review the album for the magazine and was also able to interview Reagon.

That particular album, The Women Gather, spoke about holding the space to mourn and remember the various acts of violence that daily traumatized and retraumatized not just black folks, but all people. It was about the struggle to make meaning out of what seemed senseless and meaningless. It was about love, struggle, and survival. It became my favorite album and Sweet Honey my favorite musical group. The group, as Reagon would explain to me, was made up of powerful black women activists and vocalists who together formed one of the most renowned all-female a cappella groups in the world. Reagon had been active in the civil rights movement as a college student, and speaking with her was like receiving a direct and moving transmission from someone who lived and embodied the movement. There was a strong and confident compassion in her words, and this same energy was at the heart of Sweet Honey’s art. Though they sang from the joy and struggles of their lives as black women, their music was still rooted in the experiences of Afro-diasporic people and any people engaged in the work of liberation. They sang my life. This ensemble echoed a deep sense of compassion and nurturing. When I listen to Sweet Honey, I feel cared for. They hold me and my woundedness in warmth and kindness.

Illustration by Yuko Shimizu

Soon after, I began practicing Tibetan Tantric Buddhism and was introduced not only to an extensive practice of meditation, but also to the rich mythology of Tantric deities. I was drawn in particular to Tara, the female Buddha and embodiment of compassion or the wish for others to be free from suffering. She is known as the “Mother Liberator” since compassion is at the heart of spiritual liberation or enlightenment within Tibetan Buddhism. One of my teachers instructed me to see her as friend, mother, sister, and homegirl! My engagement with her system of ritual practice and meditation deepened my sense of attunement to and concern for not just my own pain, but that of others around me.

As my intimacy with Tara and the music of Sweet Honey deepened, I began to hear the essence of Tara in Sweet Honey’s music—“Where do I go when there’s nowhere to turn to / Woman, hold my hand.” Listening to Sweet Honey and engaging in the practice of visualizing Tara and chanting mantras to her gives me a profound sense of the divine feminine. I have found both practices deeply healing in my development as a Buddhist, activist, and black queer man. As I began to study womanism, the term Alice Walker coined in 1983 to address the intersection of racism and sexism neglected by white feminists, I realized womanism had a profound affinity with Tara’s practice of liberatory compassion. Walker defines a womanist as a woman who “[a]ppreciates and prefers women’s culture, women’s emotional flexibility (values tears as natural counterbalance of laughter), and women’s strength.”2 Walker celebrates the warmth, love, and compassion of the female body in its many capacities—just as Tara the female Buddha does. Womanism restores love and compassion as key practices within a liberatory ideology, just as love and compassion are central to the very essence of Tara. As I have continued to deepen my personal Buddhist practice and my activism on behalf of racial healing, the songs of Sweet Honey in the Rock and Tara’s mantras have formed a centering and empowering soundscape to my work. The fierce love of Tara and of womanists like Walker wake me up every morning. They refuse to let me apologize for my being here. They bless me with the capacity to be silent, alone, and grieving when I most need to be.

♦♦♦

By supplicating with palms joined in heart-felt faith,

She quickly and easily bestows all desired benefits.

With reverence permeating my body, speech and mind,

I perpetually offer homage to the foremost and noble Tārā.

—The Praise of the Twenty-One Homages to Tārā and Its Benefits3

I was first introduced to Tara through the chanting of her mantra in my first sangha (Buddhist congregation). My sangha met weekly in a hall with a high ceiling and tall windows in Harvard Square. When we chanted the mantra, warm sensuous music filled every crevice of the space. Our version of her mantra—Om Tare Tuttare Ture Soha—was a soaring melodic chant that for me still evokes an experience of being protected, cared for, and guarded. That same year I attended a retreat in Santa Rosa, California where I was encouraged to visualize myself as a Tara during a guided meditation. Just before the retreat, I had gone through a romantic break-up and I was the only person of color in the retreat. I was feeling lonely and marginalized. As I sat in the large room with dozens of other retreatants, visualizing myself as Tara, I felt like there was someone who cared. Identifying as the deity helped me to let go of the painful experiences and enabled me to open my heart to self-compassion. During the subsequent decade, I have continued these practices. Identifying with Tara has allowed me to develop a sense of the divine feminine within my experience of masculinity. Working with Tara’s energy gives me the feeling of being a little boy running to my mother when I felt scared; it is the feeling of how she would embrace me. That’s how chanting Tara’s mantra and identifying with her image makes me feel. But exactly who—and what—is Tara?

Tara is the female Buddha of compassion and is mostly associated with Tibetan Tantric Buddhism. Called Drolma in Tibetan, her name means Female Liberator or Mother Liberator. In her most recognized form she is Green Tara, a radiant woman of color who sits on an immaculate lotus draped in the finest silks and adorned in exquisite ornaments. The most popular exploration of her origins was rendered by Taranatha, the great seventeenth-century Tibetan lama and scholar who composed The Origin of the Tara Tantra. The work is largely anecdotal, with Taranatha seeming to string together various legends of Tara’s origin and the spread of her particular practice. The narrative has the feeling of mythology and is an example of how the Tibetan conception of history is a mystical construction where time is not linear and where meaning is derived from the divine and supernatural; the mystical is privileged over historical fact.4The Origin of the Tara Tantra tells the mythical story of the origin of the first and only female Buddha in Tibetan Buddhism. Yet it is no mere story: the narrative has impacted both Tibetan and non-Tibetan Buddhist conceptions about compassion and how to practice it.

The Origin of the Tara Tantra reveals that in a long-ago time, a Buddha named Sound of the Drum emerged.5 At the same time, there lived a princess named Wisdom Moon. She was faithful and deeply devoted to the Buddha and his retinue, so devoted that she spent ten million one hundred thousand years making offerings to them. Needless to say, the retinue was quite pleased. The princess was able to accumulate enough wisdom and merit to achieve the initial stages of bodhicitta, the awakened heart. The monks were thrilled, and they encouraged her to continue her practice:

It is a result of these, your roots of virtuous actions, that you have come into being in this female form. If you pray that your deeds accord with the teachings, then indeed on that account you will change your form to that of a man.

But the princess was not so pleased with this answer. She responded by criticizing their short-sightedness, vowing to achieve enlightenment as a woman:

In this life there is no such distinction as “male” and female,” neither of “self-identity,” a “person” nor any perception (of such) and therefore attachment to ideas of “male” and “female” is quite worthless. Weak-minded worldings are always deluded by this. . . .

There are many who wish to gain enlightenment in a man’s form, and there are but few who wish to work for the welfare of sentient beings in a female form. Therefore may I, in a female body, work for the welfare of beings right until Samsara has been emptied.

Tara continued to practice for another ten million one hundred thousand years. Her meditative attainments were so great that they helped to liberate one trillion people a day. She became known as the “Saviouress,” and the Buddha Sound of the Drum renamed her Tara. In the presence of the Tathagata Amoghasiddhi (one of the five Wisdom Buddhas), she made a vow to protect and guard all sentient beings. Each day, while in samadhi, a state of meditative higher consciousness, she helped one trillion beings become enlightened and she vanquished one trillion demons each night. She would eventually be known as “the Swift one, Heroine, the Liberator, and the Affectionate Mother.” It is because of Tara’s fierce dedication to the liberation of all beings that she became so associated with compassion.

Tara is an example of a being who purified the ordinary states of her mind, ascending to the level of the divine and attaining the state of a deity. Tantra emerges out of the belief that beings are already enlightened but do not realize it yet. To be enlightened is to know the true nature of one’s own mind. In Tibetan Buddhism, tantra is a means through which a practitioner can quickly achieve realization of the nature of mind in a single life through ritualistic practice that includes meditation, chanting, visualization, and deity devotion, as well as physical and energy-based yoga practices. As the influential Tibetan teacher and scholar Lama Thubten Yeshe has written: “the tantric yogi or yogini—as these supremely skillful practitioners are called in Sanskrit—learns to think, speak, and act now as if he or she were already a fully enlightened Buddha. Because this powerful approach brings the future result of full awakening into the present moment of spiritual practice, tantra is sometimes called the resultant vehicle to enlightenment.”6 Lama Yeshe’s insight evokes the contemporary proverb of “faking it till you make it.” In this tradition, the practitioner endeavors to take on the views and actions of enlightenment before actual enlightenment is achieved.

Tibetan teacher and meditation master Bokar Rinpoche explores the nature of the deity in his work on Tara, titled Tara the Feminine Divine. He highlights the importance of two levels of reality in Tibetan conceptions: the relative and the ultimate. Relative reality is what we perceive through our senses and interact with in our day-to-day lives. This reality also includes the thoughts and emotions that we experience and interpret to be real. Ultimate reality, on the other hand, refers to the true nature of reality: an emptiness and space that reveals the manifestations of the relative to be illusionary in nature. In the relative, we are sensing things and interacting with things, but at the same time what we are interacting with is only a mental fabrication that occurs because we do not understand the true nature of our minds or ultimate reality. Once the nature of mind is understood, one perceives all reality as an expression of one’s own mind. Deities are not just located on an ultimate level but pervade both levels of reality, just as mind does. “In effect,” Bokar Rinpoche writes, “their nature is such that practicing with deities leads to the realization of the ultimate deity, that is, the mode of being of the mind.”7 Until the nature of mind is understood, there will continue to be the misunderstanding that there is an inherent duality of subject/object, or of I/other.

Tara’s realization helped her to understand the essence of phenomenal reality and allowed her to see that there was ultimately no gender. As a woman, she rejected the belief that enlightenment could only be attained in the male form. She recognized the systematic oppression of the female body in spiritual communities and refused to reproduce the patriarchal devaluing of her own body. She was defiant in the face of this oppression. Even when examining her traditional iconography as Green Tara, she defies the traditional way by which other Buddhas are represented. In contrast to the standard image of a Buddha sitting in full lotus posture, Tara sits with her right leg extended outward. This posture is an act of subversion and resistance, because what Green Tara represents is active and direct compassion. She rejects a comfortable seat, instead readying herself to respond to the needs of anyone that calls on her.

♦♦♦

The deeper we go into our suffering the more fervent the wish for the well-being of others. We act. We act because our inaction is felt as a participation in that suffering.

—Rev. angel Kyodo williams Sensei8

Tara developed a love and appreciation of the female form even in a location that did not value her body. In this way, Tara recalls some of the central insights and ideals of womanism. Womanism reintroduces the colored female body as a body of love, compassion, and kindness. This reintroduction constitutes a strategy for healing these bodies from the trauma of oppression. Womanism critiques any pursuit or idea that does not promote radical self-love to address the traumas of racism, capitalism, homophobia, ableism, and patriarchy within the experiences, bodies, minds, and spirits of women of color.

Tara’s mythology privileges the female body. Her narrative is not about a woman who is a victim of patriarchy but about one who transcends it. Tara’s resilience against othering is also an expression of the mode of female empowerment expressed by black feminist writer and activist Audre Lorde when she spoke of the erotic. In Sister Outsider, Lorde writes:

When I speak of the erotic, then, I speak of it as an assertion of the lifeforce of women; of that creative energy empowered, the knowledge and use of which we are now reclaiming in our language, our history, our dancing, our loving, our work, our lives.9

Tara’s rebuttal to the male-dominated community of monks—invalidating their claim that enlightenment was reserved for the male body—was erotic.

Tara is said to bless and encourage practitioners when they focus their formal meditations on her by helping them understand the empty nature of fear. One of the primary elements of this practice is imagining oneself as Tara. Visualizing Tara in this way encourages a direct identification with the essence of Tara and compassion. When we enter practice with the understanding that Tara’s nature is emptiness, then when we see ourselves as Tara—or any deity—we are also seeing our bodies and minds, including our thoughts and emotions, as a manifestation of emptiness. Within more popular practice, Tara is said to be ready at any time to enter into the messiness of our suffering as a personal agent of our liberation. She becomes Maya Angelou’s “Phenomenal Woman,” endowed with the audacity and sacred agency to make our suffering and liberation her personal agenda. Some wonder about the secret behind the confidence of the female subject of Angelou’s poem: “Pretty women wonder where my secret lies. / I’m not cute or built to suit a fashion model’s size”—the female speaker of the poem confides playfully—“But when I start to tell them, / They think I’m telling lies.”10 Tara’s secret is that she knows how we lose ourselves in suffering, and she comes to find us like a mother who has lost her precious one.

Within more popular practice, Tara is said to be ready at any time to enter into the messiness of our suffering as a personal agent of our liberation.

Tara is a deity and therefore she manifests on both the relative and ultimate levels. The relative is the realm where phenomena are sensed and can be interacted with, even though the relative may be an illusion, just an expression of our own minds. Yet it is within the relative that Tara emerges as a female deity of color who embodies awakened agency. She is no longer bounded by the relative. Rather, Tara manipulates the relative to benefit other beings who are hurt and lost in believing in the realness of the relative.

A womanist reading of Tara lends itself to a revised understanding of engaged Buddhism. Engaged Buddhism has emerged over the past few decades as a framework for understanding how Buddhists can integrate practicing the Dharma with social justice issues. Often, engaged Buddhism is understood to mean that practitioners use the Dharma as a tool to gain deeper insight into injustice and to craft strategies to act dharmically in the world as agents of change. But in my experience, it is the Dharma itself that begins to work within our own minds. As agents and subjects of the Dharma, we engage with the others around us in a way that is more kind, patient, loving, and wise, but also more direct.

A compassionate practice of the Dharma that is informed and inflected by womanism also helps to highlight the ways in which engaged Buddhism in the United States has privileged a white perspective. If womanism is indeed concerned with the experience of the colored female body, then engaged Buddhism as practiced through womanism compels us to listen to and empower those who are othered in liberation struggles. It helps us to understand the ways that those othered bodies suffer in contemporary society. Speaking of the sensitivity of the colored female body, williams contends:

So black female bodies know suffering—that is the nature of their existence in this society—. . . therefore, they know liberation when they see it and they are not capable of not seeking that liberation on behalf of others. Because that’s what liberation is, that’s what liberation actually gives rise to. You can’t possibly come to know the depths of suffering and then have any wish other than to not only be free of your own suffering, but to have others be free of their suffering.11

Thus williams reveals the intimate connection between suffering and liberation as experienced by the colored female body, a body she believes has been the most traumatized by oppression and the body womanism emerged to heal. To privilege the voices of these bodies is to gain insight into the nature of inequality and to offer a lens through which we can understand how violence is replicated even within social justice struggles.

When viewed through this lens of womanist-informed compassion, #BlackLivesMatter reveals itself to have been created by those whose otherness has resulted in an accumulated trauma that calls to be acknowledged and healed through compassion. The movement interrogates both the gross and the subtle ways that systematic oppression damages the self-esteem of the colored other.12 The way that womanist ideas cultivate love and compassion, not just for others, but for those most traumatized, can provide the foundation for the liberation of not just the colored female body, but of any colored body that is systematically othered.

♦♦♦

Until the killing of black men, black mothers’ sons

Is as important as the killing of white men, white mothers’ sons

We who believe in freedom cannot rest.

—“Ella’s Song,” Bernice Johnson Reagon13

Several years ago, I heard a teacher explain how important it was for her to relate to Tara in her practice as a good friend; this was an instruction to develop intimacy with the deity. The teaching had a profound and lasting impact on how I would eventually relate to Tara. Years later, I would find myself succumbing to the weight of accumulated racially based trauma. I was deeply unsettled and pained by the deaths of Michael Brown and Eric Garner. I felt as if I was in mourning with and for the world. Every dead black body I saw on TV or social media was like seeing my own. I was the one having a hard time breathing, like Garner, who died in a police chokehold; I was having a hard time being in the world as a brown-bodied man. I was acutely aware of my own personal trauma and of the lifetimes of psychological and emotional violence endured and held not only by myself, but by many generations before me and passed on to me without my consent. Sometimes my experience of my skin color was akin to a desperate need to rip off a burning outfit. It broke my heart to think about telling little black boys they will have to survive being black and male in a time and place that chooses not to hold them warmly or kindly.

During this time, I was moved to engage more deeply with the ritual practice of Tara. This meant developing a practice of vulnerability, trust, and devotion toward an unconditional source of compassion. It meant seeing myself as Tara and engaging with her through chanting and meditating on her. It felt like there was no one else in the world besides Tara who cared about my feeling of brokenness. Perhaps the greatest kindness of Tara is how she reminds me that in order to be free, I must embrace my own suffering and allow it to teach me about the nature of how things really are. In my experience, the practice of Tara is an invitation to experience the divine feminine and to contact a sense of sacred masculinity that transcends racism and patriarchy. I meditate on Tara near my current sangha’s bronze statue, where she sits with her foot extended, ready to rise and to help. Merging my awareness with her image, I become her. By tapping into sacred feminine energy, I feel like my own sacred masculinity is balanced by its counterpart. I ask Tara to hold my hand, and she helps me to remember that I am more than my hurtings. She helps me remember to offer kindness and warmth to the one that sometimes needs it the most: myself. After my meditation on her, I feel as if I too am ready to step out into the world, like Tara, to benefit others.

Though womanist identity was not created for me, I believe that womanism offers great insights into the suffering and potential liberation of the male body. Womanism has influenced how I choose to celebrate my own body and experiences. It reminds me of the importance of loving and compassion within my personal struggle to be liberated from my own racial, sexual, and gender trauma. Meditating on Tara helps me celebrate not only the feminine body but the masculine body as well. My meditation on Tara helps me practice an ethic of healing for the woundedness of the male body, an ethic that is grounded within masculine experiences while also interrogating the violence of power and dominance.

In 1964, civil rights movement leader Ella Baker declared, “Until the killing of black men, black mothers’ sons, becomes as important to the rest of the country as the killing of a white mother’s sons, we who believe in freedom cannot rest.” This became the backbone of “Ella’s Song” by Sweet Honey in the Rock, in which “We who believe in freedom cannot rest” is repeated against a clapped backbeat. These words echo the essence of the bodhi-sattva aspiration, which is the wish of an individual to achieve enlightenment to benefit all beings. When Tara worked toward the ultimate goal of enlightenment, she believed in freedom and did not rest. She knew that in order to benefit all beings, she had to transcend belief in the relative to contact the ultimate truth of things—and then return to the relative with fullest compassion. Through her enlightenment, she transcended the relative confines of body and identity.

Tara continues to offer us an example of what it means to be free and to free others. As we pursue the work of liberation, the ideas of womanist thinkers can help us understand how certain ways of conceiving and living out our identities can be harmful, actually replicating traumas for ourselves and others. As a womanist figure, Tara shows us how, regardless of gender, loving the body and self can liberate us from the suffering of the body and self. Enacting this love does not mean reproducing harm for others. Womanism and Tara show us that love, deep insight, and compassion for our relative identities can help us to gain deeper insight into what we are ultimately. Perhaps this is the experience of Sweet Honey in the Rock that I have been struggling to articulate for years. When they sing, “Woman hold my hand,” they speak my deepest longing to be held by the Mother, to be rescued from the violence of my own self-depreciation.

Notes:

- From Sweet Honey in the Rock’s 1985 album, The Other Side. Bernice Johnson Reagon’s lyrics are copyrighted by Songtalk Publishing Company, Washington, DC.

- Alice Walker, In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens: Womanist Prose (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1983), xi–xii.

- Jo Nang Tārānātha, The Origin of the Tārā Tantra, ed. and trans. David Templeman (Library of Tibetan Works and Archives, 1981), 11-12.

- As Tibetologist Peter Schweiger has contended, Tibetan history is more similar to mythology, which functioned as “an establishing element that contributed meaning and from which normative claims were derived”; Peter Schweiger, “On the Appropriation of the Past in Tibetan Culture: An Essay in Cultural Studies,” in The Tibetan History Reader, ed. Gray Tuttle and Kurtis R. Schaeffer (Columbia University Press, 2013), 78.

- Tārānātha, Origin of the Tārā Tantra, 11–13.

- Thubten Yeshe, Introduction to Tantra (Wisdom Publications, 1987), 15.

- Bokar Rinpoche, Tara the Feminine Divine (ClearPoint Press, 1999), 11. Essentially, the deity functions as a means through which we can develop an experience of mind. Meditating on the deity leads directly to the experience of the mind. Bokar Rinpoche explains, “From the point of view of the path leading to awakening, those deities appear as external to our mind, as an expression of the buddhas to help us in our progress, because of dualistic thinking” (12).

- “Social Justice and Buddhism: An Interview with angel Kyodo williams,” Omega Institute for Holistic Studies, July 29, 2015, www.eomega.org/article/social-justice-buddhism.

- Audre Lorde, Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches (The Crossing Press, 1984) 55.

- Maya Angelou, Phenomenal Woman: Four Poems Celebrating Women (Random House, 1978), 3.

- Rev. angel Kyodo williams, “Women and Social Change,” Felicia Sy, October 2014.

- While we can develop sensitivity to our pain through self-compassion, we extend that knowingness of our discomfort to developing a knowingness of others’ discomfort. We begin to understand that there is a community that is shared by all beings, with pain as a part of our experience. Suffering arises from our lack of understanding the true nature of our minds and phenomenal reality.

- From Sweet Honey in the Rock’s 1988 album, Breaths. Bernice Johnson Reagon’s lyrics are copyrighted by Songtalk Publishing Company, Washington, DC.

Rod Owens is a core teacher at Natural Dharma Fellowship in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and a second-year master of divinity student at Harvard Divinity School, where he studies the intersection of Buddhism and social change. He, Rev. angel Kyodo williams, and Jasmine Syedullah are co-authors of Radical Dharma (due out in June 2016 from North Atlantic Books), which explores race and oppression within American Buddhist communities.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.