Featured

Giving the Ghost a Voice

Contradictory feelings about race can be honored in Buddhism.

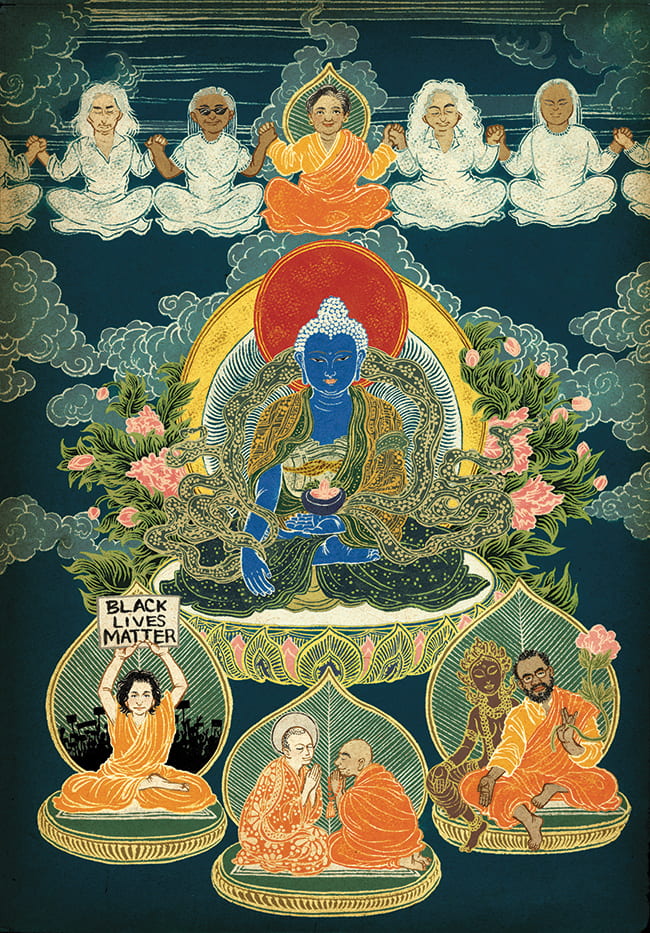

Illustration by Yuko Shimizu

By Bryan Mendiola

I didn’t realize how much I had been skirting issues of race in my life until my Buddhist path, quite unexpectedly, led me right back to them. When I completed my graduate training as a psychologist about eight years ago, I was convinced that I would not embrace the work of multiculturalism and diversity again (at least outside my professional life)—unless it was in a space of both understanding difference and skillfully working with the powerful emotions that arise in that understanding. For as powerful and awakening as my early multicultural training had been, I was often left in more confusion, anger, and resentment, not knowing how to actually work with personal issues of race in my everyday life.

But in my Buddhist study and practice in subsequent years, I found the understanding and the skillful means I was seeking, and my relationship with race has been evolving ever since. For the last several years, I have been involved in the diversity and inclusion work of my sangha, first as the chair of the Diversity Committee at Shambhala Boston, developing and facilitating a regularly meeting meditation group to explore issues of identity and culture, called “Who Are We?” More recently, I began working with the Diversity Working Group of Shambhala International to address multicultural competence training as well as curriculum and program development.

In essence, the diversity work I’ve done the last few years has been a combination of 1) the spiritual practice of investigating the mind and heart, and 2) a continual and mutual sharing of stories of personal, cultural identity—stories that make the invisible visible; give voice to that which feels silenced in us; and allow space for others to explore and express who they are, however vulnerable or insecure that may feel. In the “Who Are We?” meditation group that I facilitated, participants would meet twice a month to practice meditation and engage in dialogue about personal experiences of culture and identity, and how the Dharma impacts those experiences.

As a foundation for our group discussions, we provided the following guidelines: sharing more from personal experience than conceptual mind; listening from a place of openness and curiosity; being engaged and present at a physical and psychological level; respecting other people’s identities and perspectives; and sharing responsibility for safety and nonjudgment in the group. In the Shambhala community, this is what is known as “social meditation.” Meetings have focused on topics of racism, gender identity, sexuality, dating and relationships, age and aging, mental health, and class and money. Discussion questions have included the following: What is your relationship to whiteness? How did your family of origin discuss mental health issues? Where do you meet your comfort edge when it comes to gender expression? What is an experience you’ve had of feeling excluded because of your identity/culture? What are your views on growing older? How does class and work reflect your values, expectations, and aspirations?

One experience that stands out for me came while leading a group experience during a fall 2014 leadership retreat for a culturally diverse group of young adults in their twenties and thirties. After a period of sitting practice and establishing the group guidelines, I initiated the discussion with the following: “What are the first three words that come to mind when you hear the word ‘women’? What meaning do you make of these three words specifically?” After several participants shared their stories, one young woman opened up about how the words she thought of reflected positive qualities of womanhood, denoting strength, intelligence, and beauty. But then she expressed, with great vulnerability, how in all areas of her life she secretly denies that she herself has any of these qualities. No one in her life was fully aware of how she belittled herself, and she was clearly pained by this lack of awareness. This was something she had not thought about in this way or shared publicly in this manner. Her story seemed to stop the room cold, leaving many people at a loss for words.

This left me with an increased understanding that we all suffer around our identities. As much as we may seek to know the painful experiences that others may have, hoping for intimacy and connection, there is a part of us that also doesn’t want to see or acknowledge this suffering—even with those we care most about. Perhaps really seeing the truth of people’s experiences means that we have to face the passion, the aggression, the ignorance that exists, not only in the world, but also within ourselves. My commitment as a Buddhist practitioner is to the awakening to truth, the truth of reality, the truth of suffering. We share our stories to share our truth, to share our pain and vulnerabilities, to share our healing and growth—so that we can see more clearly the greater, collective truth of reality. Perhaps sharing some of my own story regarding race can contribute to that collective truth.

Illustration by Yuko Shimizu

There is one important caveat: I don’t know how to talk about race. The term Asian American was never spoken in my home growing up, and this quietly implied that it should not be talked about, that this was not how we should think of ourselves. In contrast, there was never any doubt that we were Filipino. This was celebrated and honored through food, family, religion, and community. It was the cultural waters we swam in. But race was on the periphery, like a ghost that no one wanted to name or acknowledge. Even as I write this, I feel my anxiety well up over being misunderstood or being misperceived as representing more than myself alone in my views. I even struggle with whether or not my story is really about race or deserves a place in a dialogue about race. But, before I had any words for race in early adolescence, my experience was about sadness, loneliness, and depression. And however uncomfortably, I do know how to talk about those things.

Perhaps for most families, mental health conversations are off limits. But in my Asian family, I sensed there was a preference, a pressure, to remain ignorant and silent about “problems.” Any kind of outward unhappiness was quickly followed by inward guilt and shame, often because of the continual reminders of how successful, blessed, and fortunate we were as a family, living and working the way we were. Anything perceived as complaining was frowned upon. So, as depression took hold in my early adolescence, it manifested outwardly as quietness, shyness, and politeness—the very hallmarks, conveniently, of a good Asian boy. What I didn’t realize at that time, of course, was how that kind of invisibility would become a common thread in both my own story and the stories I came to know of the racialized experience of being Asian American.

My depression was rooted in never finding a place to call home. There was a perpetual sense of not belonging anywhere, never quite fitting in, even in my own supposed social groups. I often felt too Asian to feel completely a part of the white suburbs that surrounded us, and too white or too American to be fully integrated into Asian communities or other communities of color—even into my own family at times. I longed to be able to look into the world of television and magazines to see and hear someone who looked like me, talked and thought like me, and could give me an example of what I could become. In my young mind, the only way I could make sense of a world that didn’t have “me” in it was that “me” didn’t matter.

And so I quietly began to tear myself apart—feeling tortured by who I was and what I looked like. This is a nuanced and slippery, but hallmark, feature of my own experience of being Asian American. My painful experiences around race feel less about overt acts of racism and discrimination, less about systemic injustices, and more about a perpetual experience of feeling unseen and silenced. One of the great challenges in finding a voice in the dialogue of race is that, as an Asian American, it is remarkably difficult to name the “problem,” because it is one more of absence than presence. It feels less a problem of having an identity undermined or marginalized, and more a problem of not having an identity—visible, coherent, or identifiable—in the first place.

In my experience, there are many factors that contribute to this sense of invisibility. While never directly stated, the perceived message from my Asian and Asian American communities is that I’m not supposed to have a distinct voice in sharing who I am and what my life is about. There is a natural inclination toward a collective mindset and to gauge properly whether or not my experience appropriately represents the collective—a compulsive checking in with the group for approval and permission. And the implicit message from the group is: “Don’t speak for the rest of us—especially if you’re going to talk about our problems.” I was often left feeling alone and voiceless as an Asian American, without clear role models in the media or popular culture, and I was given few historical figures of social change to identify with. Even widely known Asians in history who represented social causes have been marked by a seemingly stereotypical passivity, meekness, or unemotionality, qualities that I did not wish to embody in my own life. Moreover, there was no singular, tangible source of injustice that spoke to my experience as an Asian American. As a first-generation Asian American, I grew up with significant economic and academic privilege. Issues of money and education were never at the forefront of my struggles, which often left me wondering if my own suffering was even justified or valid.

And yet, I felt it—as real and as true as anything in my life. At the heart of my struggles as an Asian American has been a tremendous internal conflict, if not an external one. This conflict within is built around a profound and unrealistic pressure to succeed at a societal game I might not even feel a part of, but that may be the chief means by which I judge my own worth. At the end of the day, when the game is not being played, maybe I’m the one who doesn’t have a home to go back to. I can adapt and blend in just enough to get by, but never enough to actually belong. So maybe I end up belonging only to the game itself—only to an illusion—even if it’s not one I value, agree with, or buy into. Perhaps because I can play it, I never stop to ask myself if I should play it. And what seems to be the fallout is an invisible experience of suppressed frustration, passive-aggressive competition, hidden identity crises, and underlying emotional turmoil: a powerful storm brewing just under the surface of a peaceful, calm façade.

Put simply, what depression and race largely meant to me during those formative years of my life was an experience of self-hatred. Hatred of the shape of my lips and nose, the discoloration of my skin, the lack of proper physique, or the hair that would never quite look like a white person’s. Hatred of the way I talked or never talked. Hatred of my self-consciousness and lack of confidence, as well as of my pretending to be confident. Hatred for always feeling alone, regardless of how many friends I had or how much family or community surrounded me. Hatred for even the ways that I was loved by others, because I knew in my heart that their love was misplaced. Hatred of my constant comparisons to others, even within my social circles, because I, too, succumb to the pressure to succeed and perform and perfect myself. Hatred toward this life of mine in which there was no other person in the world mirroring back some clear semblance of myself and my experience. Hatred, at times, of myself for wanting to give up on life altogether.

Though I was not fully aware of it at the time, it was all this hatred that led me to psychology as my profession and to Buddhism as my spiritual practice. In both, there was a discipline and a path to realize my own mind and heart, to learn how to create a space in my life where I could come to terms with who I was and how I felt. Buddhism in particular provided me with a view of life that simply made sense and validated my experience of confusion, suffering, and emptiness. It allowed me also to find refuge in a life of quiet reflection and stillness that felt so natural to who I was, yet which, for so long, I had judged as deficient or unworthy. It even gave me something to be proud of in my Asian identity, as I could look upon images of a calm, wise, and beautiful Asian man who could live simply, think radically, and affect countless people. I, too, could be Buddha. Perhaps in my more naïve moments, I thought to myself that I, too, could shave my head, smile nicely, sit still, and feel worthy. As misguided as that might have been, it meant something important to me, something I had been missing for much of my life. I was learning that I could actually make a home with myself.

Moreover, Buddhism by its nondualistic, dialectical nature, gave me permission to honor all my contradictory feelings about race—both hating myself and loving myself; both identifying with race and deconstructing race; both grounding and empowering myself in identity and continually questioning it and allowing it to fall apart. Still, as I began to expand my spiritual path and embrace community, I would spend years exploring different sanghas and battling old demons of feeling different, out of place, and not understood. Time and again, I would find myself in predominantly white sanghas with predominantly white teachers, often the only person of color at a gathering or a retreat. I was very much accustomed to assimilating to white culture and acting my typical quiet, accommodating, and polite self. But with each passing year I had a longing for things to be different. At the time, I had yet to hear a teacher’s voice that resonated with my own heart, particularly when it came to issues of culture and identity.

I did not have to become another silent, faceless, uniform addition to a Buddhist community. I could be myself.

What I found in the Shambhala Buddhist community was not altogether different—but it was different enough. In the local community of Boston, where I was living at the time, many other young people filled the meditation hall each week, of various colors, genders, sexual orientations, and economic backgrounds, and gatherings were rooted in the practice of being authentic, genuine, and openhearted. While the community at large was still predominantly homogenous and white, there was a felt sense of open-mindedness and curiosity toward exploring difficult, messy topics. I was immediately drawn to Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche for his unconventional style and his openness about deeply emotional experiences of loneliness, anger, and sadness and how transformative they can be. Here was a teacher who I felt was speaking directly to my experience as a human being, at a raw and heartfelt level. His teachings, and the teachings of his son, Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche, challenged me to be fully myself by not rejecting any aspect of myself. I did not have to become another silent, faceless, uniform addition to a Buddhist community. I could be myself, find my own voice, and share my own truth, with all the messiness that comes with that.

My first several years as a vipassana and Zen practitioner provided the early stability of sitting practice and the foundational teachings of Buddhadharma. I gradually learned what it meant to be with myself and my emotional life more directly. But what I also gained through my study and practice in Shambhala was how to work with my view of myself on a practical and basic level. At the core of Shambhala teachings is what is called basic goodness, a term coined by Trungpa Rinpoche. My understanding is that it points to an innate and fundamental sense of openness, purity, wholeness, and workability underlying ourselves and all of existence—what can also be thought of as Buddha-nature, egolessness, absolute bodhicitta (awakening mind), tathātā (“thusness,” or things as they actually are), and jñāna (knowledge, as in the Greek gnosis). Every teaching and practice is meant to promote awareness and trust in this primordial nature, and by doing so, we learn to not be afraid of ourselves, our experience, or the suffering of the world.

The times that I have realized glimpses of my own innate goodness have been deeply emotional and healing experiences. I’ve seen the myriad of ways that I hide from myself and from others, out of fear, embarrassment, and shame. And I’ve learned that confidently proclaiming who we are, in our full humanity, is truly an act of spiritual warriorship. At its basis, our experience is dignified, worthy, and workable. What this has meant for me is that not only are the realities of race fundamentally workable, but also that seeing and moving beyond my racialized existence is fundamentally workable. I’ve learned that the spiritual path is all-inclusive—and that I already have everything I need to continue moving forward.

As I continue to engage in dialogues in my professional, community, and home life about issues of race, culture, and identity, I see how some of my life’s deepest meaning is found in working with that which has been the source of some of my deepest pain; in ultimately facing the question in my own life of what it means to actually be seen and heard. Who am I if I am no longer invisible and silent? What story will I share of myself? What will people see and hear in it? I’ve learned that no matter what our particular cultures and identities may be, they can be both a source of power and privilege and a source of suffering and stuckness. They can keep us small and silent, and they can wake us up and empower us like nothing else, if we allow them. I believe the stories we tell of our cultures and identities, whatever they may be, can help ourselves and others to have a grasp and appreciation for the greater truth of reality. Perhaps it is the therapist in me—or maybe the Asian American Buddhist in me—but in my experience, this is how social change comes about: by unearthing and awakening that which has remained hidden within us and among us, and mourning, healing, and growing together. It is a process of embracing ourselves by giving voice to our stories—and having that voice heard and honored.

Bryan Mendiola is a Filipino/Asian American psychologist and a student of Shambhala Buddhism. He lives with his wife and son in Western Massachusetts.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.

A profound reflection on the intersection of Buddhism and the exploration of race. The author’s personal journey, navigating complexities and emotions, highlights the transformative power of mindfulness and inclusion work within the Buddhist community. It’s inspiring to witness the evolution of one’s relationship with race through the lens of spiritual practice and community engagement.