Featured

Wisdom of Webs

An Interview with Sarah J. Karikó

Orbweaver web. S. J. Karikó

Sarah J. Karikó, PhD, is research director of Gossamer Labs, LLC, and associate of the Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology at Harvard University. She is an arachnologist, educator, and artist who uses her experience researching spiders to understand the complex relationships within the web of life and to create better ways of caring for our interdependence among species and systems. Natalia Schwien sat down with Karikó to discuss how spiders have impacted her thinking.

Harvard Divinity Bulletin: Why would you have us pay attention to spiders?

Sarah J. Karikó: Spiders seemed like a narrow field until I realized they touch nearly everything, from medical to military advances and from fashion to food. They are key contributors to ecological balance and remind me how inextricably interconnected we are. Spiders are architects, designers, and high-stakes negotiators. I turn to them to help me better understand our world. Spiders have adapted to changing climate conditions long before our young species—evolving over 400 million years into over 50,000 described species—adapting to nearly every habitat across Earth. They do seemingly impossible things. Orbweaving spiders create silken structures that allow earthbound oxygen-breathing animals to make a living suspended in air. Spiderlings can be found ballooning over Mount Kilimanjaro, over skyscrapers in Chicago. Some spiders have found a way to live underwater in diving bells of their own creation, making silken staircases between worlds. And spiders have been part of human stories for ages, from the story of Muhammad, the cave, and the spider in the Qu’ran, to stories of Anansi from West Africa, to the Lakota stories of Iktomi the trickster spider, to E. B. White’s Charlotte’s Web. So, what can we learn from spiders?

Bulletin: Can you tell me a little about the journey that led you to this fascination with spiders?

Karikó: I grew up reading National Geographic and was especially drawn to the stories about rainforests and mountains, as well as the mysteries of the underwater world that Jacques Cousteau was opening up. These stories were seeds for my imagination. I lived in a city, so my childhood was filled with “expeditions” into our unfinished basement and our back garden. I spent a lot of time washing rocks with my neighbor Mrs. Newell, an elderly lady geologist who was the first woman I remember who had her own tools—she had a rock hammer in her kitchen that was instrumental in bringing all those rocks and their stories into her collection and my life. (An early lesson on the importance of tools for exploration and discovery.) I’d race next door after elementary school, walk through her husband’s home laboratory (he was a retired engineering professor) filled with scientific instruments like oscilloscopes, through their living room past a painting of the Peaceable Kingdom, into their kitchen where I carefully carried each rock to the sink to wash and dry and put carefully back with its collecting label. Each rock was a story of place and time. They were marvelous to hold in my little hands—puddingstones, mica mirrors, sandstone roses.

Later, I found a rock that appeared to change color in my hands—jade, cobalt blue, violet. It was unlike any Mrs. Newell had in her display cases. I wore my parents down asking them to bring me to a museum where I could find out what it was. I was brimming with excitement as they brought me to a museum here at Harvard, and I got to look at the rock and mineral displays. But I couldn’t match it. Eventually, my parents found an adult who would look at my rock and speak to me. I don’t remember who it was, but I do remember they told me that my rock was coal. It couldn’t be, I thought—coal was something Santa brought children who had misbehaved, and coal covered my grandparents’ place with soot. I asked the adult to please look again. Maybe if they held it differently, they could experience that magic too. This rock was so amazing that I secretly thought it could be something very rare or—even more exciting—something new.

Among other things, I now describe new species to science and, together with a team, I have explored the structural origins of color in a tiny, vibrantly colored spider from Madagascar. My curiosity about the natural world was boundless then and continues today. It could have gone many ways—pollinators, polar bears, plankton. One of the animals I encountered regularly back then in the basement and garden was spiders.

Bulletin: Can you tell us a little more about your work?

Karikó: I conduct research on spiders that I’ve studied in the field, some of which are now held in the Invertebrate Zoology Collections at the Museum of Comparative Zoology. I am currently studying female mound building spiders, focusing on their reproductive behavior and care for future generations. They are the only known spiders in the world to construct a mound over their young. They find a nook in a rock, then work with what they find around them to create intricate, artful mounds over their egg sac—the mounds reflect little microcosms of their surrounding worlds.

Phoroncidia vatoharanana Kariko, 2014 (Araneae: Theridiidae). Lateral view of a female. This species was described from animals found near the bush camp and on expeditions in remoter regions of Madagascar. S. J. Karikó

I also serve on the Spider and Scorpion Specialist Group of the International Union for Conservation of Nature and was part of a team that did the largest assessment of spiders’ conservation status to date. I interweave my biodiversity research into many programs that I’ve designed for places ranging from a pediatric oncology and hematology ward, to national and state parks, to the Juilliard School, to the Irish Museum of Modern Art, to the National Academy of Sciences Engineering and Medicine. I’ve been invited to collaborate with a wide scope of people, including a White House pastry chef, a choreographer, and a state park manager. So, I am contributing not only to our scientific understanding of biodiversity but also exploring what insights different fields can learn from spiders to help meet this crucial moment in time.

Bulletin: A term that you use a lot is “interdependence.” How did this word become so central to your writing and work?

Karikó: When I was a young researcher, I conducted fieldwork in Madagascar during a time of great political unrest. I witnessed the interplay of politics, supply chains, environmental impact, public health, and personal wellbeing. These deep visceral lessons of interdependence that I experienced subsequently shaped the lens through which I’ve approached my work. I conducted research from a remote bush camp in the rainforest where I lived with a Malagasy team during the week and by myself on weekends. Our camp comprised two sleeping tents and a large tarp with no walls. It was deluxe in that we had two three-rock cook fires, a bamboo bench, and a worktable where I set up my microscope. There was no real separation between us and the many others who moved through—like lemurs, chameleons, and the occasional Fossa fossana and aye-aye. Nelicourvi weaver birds wove their nests in the branches just above my microscope, giant land snails mated on the path to my tent. Despite our best efforts, mongooses opened our once-a-month supply of powdered milk. Between rains I’d see their little pawprints and all the places they traveled—white powdered storylines radiating across red mud of the forest.

Working near the bush camp in Madagascar, in the early 1990s, with Telo Albert, now Ampanjaka (King) of Ambatolahy. Courtesy S. J. Karikó

Bulletin: You lived in this interconnectedness while there.

Karikó: Yes, in too many ways to describe. It was a gradual accumulation, a layering over time of many experiences. Some were at an individual body scale, like discovering I made a good host animal to invisible parasites that are difficult to evict once they take up residence. I was in a region with terrestrial leeches and was literally sharing my blood with dozens (sometimes hundreds) of them daily.

Then there were experiences at the systems level. Connections among societal infrastructure (whether supply chains or road infrastructure) were easily disrupted. There were few if any paved roads at that time, and roads that existed turned into vehicle-swallowing mud during the rains, disrupting the availability of food, fuel, and supplies. Letters to someone outside the country could take a month or more, if they arrived at all. Just to communicate with people at the research station, I’d need to hike out or have someone carry my note through the rainforest, find the person, give them my message, wait for a response, and then carry it back to me—perhaps that day if it wasn’t too late or stormy, or the next day . . . or the next. There was much more space and time between communication.

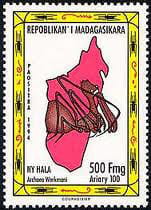

Malagasy spider postage stamp

At the time, I didn’t really know how to respond to all I was experiencing: bridges being destroyed, traveling through a tunnel of flames—the forests burning on both sides—people affected by malaria and advanced leprosy. This multitude of experiences drove me to do two things: One was to design a spider stamp (based off the duck conservation stamps back home), hoping it could help in some way. I worked with the Malagasy postal service and created a stamp that highlighted this amazing little spider with quite a discovery story. These archaeid spiders were thought to be extinct but were later found living in Madagascar and were described by Rev. O. P. Cambridge. Their eight eyes are way up high, as if on a lookout turret. They have long lance-like chelicerae or jaws and cranial spines. They sweep their long front legs out into the night. Watching them in the beam of my headlamp, amid silken mists up on the ridge, amid tree ferns and vines, was like seeing nocturnal ballet.

The second thing I did at the time was negotiate the first Venom Accord between the Malagasy government and a private pharmaceutical company. I was trying to find a way to ensure that if medicines were made, resources would go back to the people and habitats where the spiders were found in Madagascar. This approach differed from what was happening at the time with some cancer drugs, for example. It’s akin to paradigms now referred to as “one health” or “planetary health.” I then came home and formalized my training at Harvard Law School’s Program on Negotiation.

Bulletin: Supporting environment and people—to some, this seems antithetical. What insights from studying spiders can help us address these urgent needs?

Karikó: Spiders help me think about how we can better care for our interdependence. While it can be messy for us humans to unravel and address complex intertwined problems, orbweaving spiders use interconnectedness to their advantage. They spin elegant, wheel-shaped webs you might see shimmering with diamond-dew in the morning light. When they are in the middle of their webs, they’re at the center of a myriad of interconnections and can synthesize information through silken lines extending out into the surrounding world. Impact anywhere in the web ripples out to affect even seemingly distant parts. Orbweavers typically stay connected by positioning their bodies in the central hub or “listening” to the vibrations through a line connected to the center from a retreat. They are positioned to synthesize multiple lines of information from their environment, to inform decisive action. When something large, like a dragonfly, hits an orbweb, threatening the integrity of the structure, the spider can cut lines to free it.

Studying this interconnectedness has really shaped my way of thinking about the interactions between species and systems and how we might care for ecological and societal systems together. An orbweaver reminds me that impact anywhere affects even seemingly distant parts. Both intended and unintended consequences of our actions can affect far reaches of our world. When researchers were searching for sources of squalene during the race for a coronavirus vaccine, I did not hear enough simultaneous discussion of how the source would also be cared for, whether taken from sharks’ livers in the deep sea or soapbox bark in Chile. Paying attention to how we do things and care for impacted communities matters.

Einstein is often attributed with saying problems cannot be solved by the same consciousness used to create them. To meet the scale and scope of today’s challenges, we need a shift in consciousness and a new framework to create solutions in balance with Earth’s life-support systems. We need to consider our relationship with each other and with other species as integral to finding new solutions. And we especially need to include the smaller majority of animals, like invertebrates who are contributing behind the scenes to our daily lives, whether we recognize them or not. They comprise over 95 percent of animals on Earth and contribute to pollination, soil architecture, and ecological balance. What would we do without them? Through a lens of our interdependence, we can address the tiny and vast together.

Bulletin: What are some of the obstacles to embracing a framework of interdependence that concern you the most?

Karikó: Despite our connections through the World Wide Web, we are losing our connection with the living Earth who sustains us. It can be difficult to understand how things are connected, especially in the United States, since teaching, research, funding, and leadership have long been siloed and structured around human-imposed divisions, and this is then compounded by a widespread knowledge gap of other species. A global study published in 2021 by UNESCO reported that only 19 percent of the global education curricula referenced biodiversity. Despite rolling out funds for the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, the Inflation Reduction Act, and the CHIPS & Science Act, the role of biodiversity has not been commonly acknowledged as vital to national security, public health, or the economy. It’s even difficult to find biodiversity mentioned in announcements for these funds. We are often missing the full picture. And so, although roughly 190 countries signed the COP15 agreement to halt the loss of biodiversity, the United States was one of two countries that did not.

But our daily lives are interconnected with other species, whether we recognize it or not. We’re on a planet where oxygen is produced by other species like plankton. These tiny, microscopic organisms make up less than 1 percent of all species who photosynthesize carbon dioxide, but they produce at least 50 percent of Earth’s atmospheric oxygen. We need them to produce what we breathe. They’re also critical for carbon cycling in oceans, important for regulating climate and providing the foundation of foodwebs—feeding herring, tuna, and eventually some of us. Yet we rarely create policies or systems that reflect our inextricable connection with these other species. Ocean “dead zones” are on the rise. Oceans are losing their breath. We need leaders who pay attention to declines in the oxygen budget while also making sure plankton are included in long-term planning while caring for human needs. Communities from coast to coast are already impacted by low-dissolved oxygen levels in seawater, contributing in part to what the secretary of commerce has declared to be fishery disasters—such as the disappearance of Alaskan snow crabs and die-off of Long Island’s Peconic Bay scallops. What happens if the oceans are no longer able to produce enough oxygen? Rachel Carson warned of a “Silent Spring.” What will we do to prevent a breathless one?

Bulletin: How do we work together towards systemic changes?

Karikó: We need to address the gap in biodiversity education. To shift from siloed solutions to integrated ones focused on interdependence. Critical to this is traditional ecological knowlegde and the communities who hold it. Indigenous peoples are safeguarding 80 percent of biodiversity despite being 6 percent of the global population.

With COP15’s recent landmark agreement to preserve biodiversity and less than eight years to meet the United Nations’ 2030 sustainability goals, the United States has a once-in-a-generation opportunity to transform how we live together on Earth when it could not be more critical. The United States needs a Department of Interdependence whose main mission is to better care for the often-invisible connections that link us together. There is precedent for creating federal executive departments during times of crisis—most recently the Department of Homeland Security after 9/11, and earlier, the Department of Energy and Environment during the ’70s fuel crisis. Are we at another critical point yet? To be clear, I’m not suggesting centralized control with one entity pulling all the strings, but rather a way to elevate human response by bringing multiple ways of knowing together and synthesizing them into actions that simultaneously prioritize ecological and societal systems together.

We need a nimble FEMA-like response team that can help meet and exceed the UN 2030 sustainability goals. We need to address the real, complex web of connections among watersheds, vaccines, transportation, the deep sea, the air we share. To assess and address cumulative, often disproportionate, impacts on communities. To examine the intricate interplay of issues of justice, biodiversity, food security, public health, and environmental impact, and find different ways to move forward together. With the combined rollout of an estimated 2 trillion dollars over 10 years, the United States is uniquely positioned to transform infrastructure and systems. This is a tremendous opportunity to envision solutions addressing multiple issues in the built and natural environments together, while healing past harms.

Bulletin: Given divisions in our country, how can we collectively make the most of this opportunity?

Karikó: To be sure, it is difficult to unite in this political climate. But despite divisions tearing the social fabric, a 2020 Carr Center poll reported nearly all Americans (95 percent of Republican, 94 percent of Democrats) believe “access to clean air and water to be an ‘essential’ right.” Let’s build upon this common ground. American infrastructure is a complex web itself—public and private entities working together on energy grids, communication networks, transportation byways that crisscross the land, waters, and sky. A framework of our interdependence can help shape and coordinate efforts across these many lines to develop healthier ways of connecting people, information, and goods, while also caring for biodiversity.

Bulletin: We need to rethink our ways of engaging the challenges that face us.

Karikó: Yes, we need bold new models and infrastructures to move forward, and we need courage and creativity to envision, test, and implement them. We need to be nimble in identifying and addressing unintended consequences. Toward that end I’m developing a Wisdom of Webs leadership program to empower and nurture a cohort of leaders wanting to innovate solutions that better care for ecological and societal systems together. I am doing this with a team that includes an orthopedic surgeon, a commander in the U.S. Navy Medical Corps., and a Lakota educator and artist. Our onsite, experiential programs support conditions for cross-pollination, creativity, courage, compassion, and change.

In addition to interweaving learning about biodiversity with tools supporting creativity, we use negotiation trainings to help leaders work together toward outcomes aligned with the interdependent nature of our world. These trainings are based on case studies from biodiversity field work and examples from the natural world, such as high-stakes negotiators like some spiders. Participants can then apply these skills in their own research and collaborations, such as an HIV/cancer researcher at Dana Farber who was able to negotiate critical access to a Tecnai F20 cryo-electron microscope for his research at a time when there were only two in New England. To support this work we are developing relationships with individuals, institutions, and transformational philanthropists who can help us amplify the beneficial ripple out throughout the web of life.

But we can start where we are, with what we have around us. And we can use traditional spaces, like museums and national parks, in new ways to connect people across siloes.

Bulletin: I think of your involvement in creating “Requiem for a Rhino,” at the Harvard Museum of Natural History on May 7, 2018, as an example. Could you tell us more?

Karikó: Yes, I used a museum gallery to create “Requiem for a Rhino,” which grew out of the news in March 2018 that Sudan, the last male northern white rhino, had died. This happened in my lifetime, while I was doing my research among friends and colleagues, all of whom are concerned about biodiversity. In the 1960s, there were 2,300 left in the world, in 1970s there were 650, by the 1980s there were about 350, and by the 1990s there were only 30. And now there are only the two female northern white rhinos left. On our collective watch we have lost one of the world’s largest megaherbivores. I felt that it was really important to disrupt business as usual, to pause and reflect on our collective impact on other creatures, and to think about how to do things differently. So, I organized a team of colleagues at Harvard, and we created a requiem for Sudan at the Harvard Museum of Natural History. It was not a public event for the museum, but for university researchers, students, and staff.

Participant at “Requiem for a Rhino” pictured with Gesner’s 1553 Historia Animalium and silhouettes of flowers from Sudan’s habitat. S. J. Karikó

We played a recording of the Memorial Church choir singing “Walk Softly on the Earth,” as people gathered in the museum’s Great Mammal Hall, a dramatic two-story gallery of mammals and birds. We were standing among bison, okapi, chimpanzees, gorillas, and a giraffe, and underneath several hanging whale skeletons, as well as Steller’s sea cow, an animal that went extinct less than 30 years after it was first described. Then we listened to an interspecies duet, with a viola responding to recordings starting with the calls of birds who were in Sudan’s habitat and finishing with the last male Hawaian ‘ō‘ō bird, calling for a mate who would never come. People were invited to walk through the gallery and not only to notice the beauty of these other mammals but to read the extinction labels and consider the role that humans have played. Librarians had brought Gesner’s 1553 edition of Historia Animalium, with Albrecht Dürer’s 1515 woodcut print of a rhinoceros—the very first print of a rhinoceros that we have. We had worked with the herbarium to get silhouettes of the flowers that were in Sudan’s natural habitat. Attendees were invited to write, draw, and express their connections with the stories of these species and the human impact upon them. They then hung their drawings and reflections on the vitrines throughout the Great Mammal Hall. It was a multidimensional dialogue of palette and color, of rememberings, grief, celebration, and responses, from people who don’t usually come together.

With the requiem we wanted to create something different from an exhibit space, and it felt different for me, because it invited that combination of reflection, creation, and connection. I think this sort of interaction is critical if we are going to change systems, because it challenges us to open ourselves to curiosity and change, so that we can shift these deeply siloed systems to integrated ones and transform how we move together across Earth.

Bulletin: As we open ourselves to transformation, what are some of your reasons for optimism?

Karikó: The power of beauty and wonder, and our capacity for creativity and collaboration. Currently, I draw upon experiences like the requiem to use unexpected spaces as places of connection and collaboration. What I’ve experienced with both students and colleagues is that when that lens of our interconnectedness starts coming into focus, it opens up possibilities for seeing other connections and for innovating new solutions and approaches. And that, I think, is where my hope lies. Inspiration for creative adaption and resilience is all around us—from the dancing maps of bees, the cooperation of trees, immune strategies of marine sponges, and the strength and flexibility of spider silk. We may find that we already have what we need to address past harms and create a flourishing future.

Natalia Schwien, MTS, is an herbalist, sustainability consultant, and PhD candidate in the Study of Religion at Harvard University. She is the associate director of the Program for the Evolution of Spirituality at Harvard Divinity School.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.