In Review

Building Trust through Truth-telling

An interview with Wendy Sanford and Mary Norman

Bulletin: What do you remember about your first meeting with each other?

Wendy Sanford: It started when Mary was about to turn 16 and I was 12. My family went on a summer vacation on the island of Nantucket and rented a house. My mother was going to have what she called “help.” She spoke with Mary’s aunt, who did domestic work for my godmother. She recommended Mary, who had just graduated from high school in Virginia. My mother picked her up at the ferry boat. They came into the kitchen together, and that was when we met. Revisiting that moment from a later perspective, there was so little I knew about Mary’s life and how huge a thing it was for her to have traveled that far alone. For those first several years, Mary’s job was to know everything about me. My job was not to learn about her, but to go have my great life while she took care of everything and did all the hard work for the family.

Mary Norman: It was a job for me. Coming there and meeting you for the first time, you were such an inquisitive person. I think I may have been the first Black person that you had ever encountered. So there I was, and Wendy was just hanging in the doorway asking, “What are you doing? What’ve you got in your suitcase? Why’d you bring this? What do you do with your hair?” I would just tell her a few things. So that’s how it started out in the very beginning. She just wanted to know things.

Sanford: I didn’t stop to think, did Mary want to answer? Did she want me hanging in her doorway when she first got there, asking a million questions? Looking back at the rules of domestic service, you couldn’t say no, Mary. It wasn’t part of your accepted role to say no.

Norman: Exactly.

Bulletin: Mary, what was your experience of that early dynamic?

Norman: The whole thing was scary. To get there, you traveled by train. At that time, it was assigned white only and colored only. My mother had packed my lunch. I was sitting there, clutching my suitcase and just hoping that I would get there. I can remember being scared. My aunt met me at the station in New Jersey and then Wendy’s mother had made arrangements for me to be taken to the boat in Massachusetts by a police officer named Norm, a white police officer. I sat in the back. He asked me if I needed to use the bathroom at the gas station. Then he said nothing else until we got to Woods Hole, when he said, “We’re here! You’ve got to get on the boat.” And I was thinking, “Oh my God, I can’t swim!” There were a lot of teenagers on the boat. I think that I was the only Black person on that thing. Of course, they would look at me and giggle and it was very, very uncomfortable. Honestly, I felt like I wanted to cry. But I didn’t. So that’s how it was. We docked, and Wendy’s mother was there, and she was waving. She was very nice, so then I began to relax some.

Sanford: One of the things that we’ve talked about, looking back on it, is that my mother, who was very friendly with some of the police officers in town, probably thought this was a brilliant idea for how Mary would get from Princeton, New Jersey, all the way to Massachusetts. She had no concept that in the South, white police officers were enforcing the rules of Jim Crow, often violently. Whether or not that had been Mary’s experience, that was the general experience. The officer, Norm, ended up becoming one of her close friends in later decades. But what a choice for the person to drive Mary.

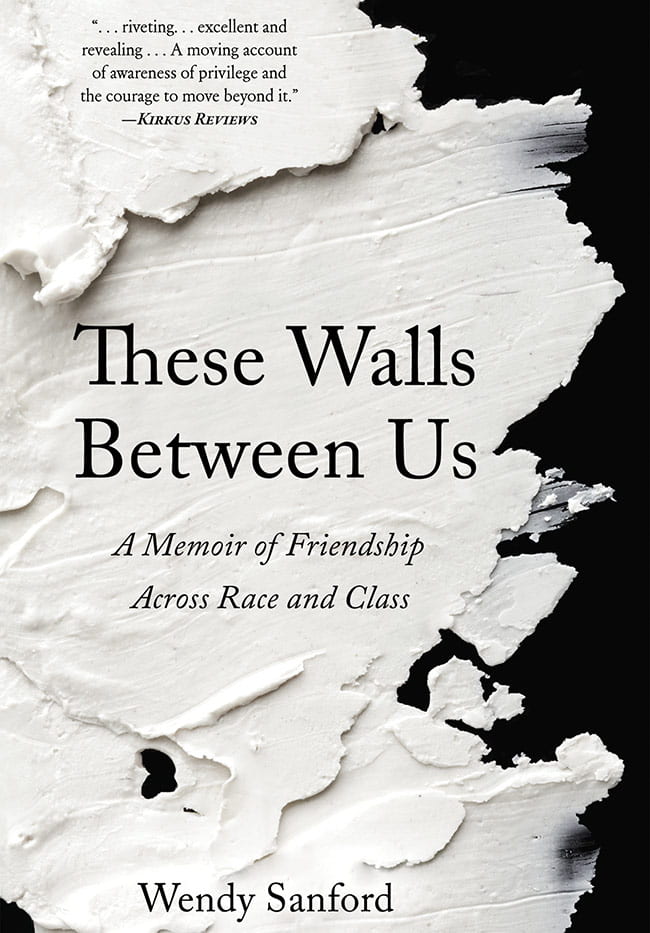

Wendy Sanford and Mary Norman. Photo by Polly Attwood

Bulletin: Wendy writes that the memoir arises out of an earlier plan to co-author a book. How did you decide to adapt that story into a memoir written from Wendy’s perspective?

Sanford: Fast forward to our 30s. Mary was still moonlighting part time for my parents and for other white families in the Princeton area. She was also working full time building a career in corrections as the first Black woman in Mercer County, New Jersey, to go to officer training school. She was really paving the way for women in that area. I had become a feminist and was working as a co-author of Our Bodies, Ourselves.1 Mary and I had both been married and divorced, and we were both single parents. Mary was using her vacation time from the correction center to do domestic work for my parents on their summer vacation. When I visited, she and I started walking the beach together at night. We just got talking on a whole different level. I probably still asked a whole lot of curious questions. That probably will never end, and we’re in our 70s and 80s now. When Mary and I came back to the beach cottage the first night, my mother was upset that we had left her alone. I understood in that moment that Mary could get in a different kind of trouble than I would. From then on, we were fairly quiet about our growing friendship. Mary, you said we had to whisper a lot.

Norman: Wendy would tap on my door, and we’d be whispering, and she’d ask, “Want to go for a walk?” I would say, “Sure, but maybe we should wait a little bit until they go to bed.” Just in case her mother wanted something, I would be there for her. We wouldn’t go out walking until after they went to bed, unless your parents went out for dinner.

Sanford: That went on for, I don’t know, 20 or more summers. We both told each other that our walks together were what we looked forward to. We tried to time it so we’d be at the beach cottage at the same time. On one walk, Mary said we should write a book together. She said no one would believe our friendship. I would say we created the book together. At first, with my white supremacy education and having majored in English in college and gotten straight As, and having worked on Our Bodies, Ourselves, I felt like I could write “our” book. Over the next few decades, I learned that if I tried to do that, it would be what Toni Morrison and others have called the white gaze. It would be me applying my gaze and calling it our book. Although I am listed as author because I did the writing, we really co-created it through many conversations.

Norman: That’s true. There were a lot of phone conversations and texts. You took notes, you remembered dates. And I did not have the time. I was working all the time, because I had to. You had the time.

Sanford: I didn’t even realize the risk of writing this memoir from my perspective until I began to listen to Toni Morrison on what white writers do with Black characters. I needed to honestly say the memoir was from my point of view, but there also had to be so much of Mary in the book for it to be useful and trustworthy. White people have written about people of color who worked for their families in ways where the white person is the hero, or where it’s, as Morrison says, a “choked” characterization. The story comes through the white person’s nostalgia or guilt. That’s why it took 30 years to write this book. It kept having to change in order to avoid these pitfalls.

Norman: You used to sort of talk around your question in the beginning. I told you, “Wendy you have to just ask me and not be afraid.” One day she was in my doorway and she wanted to ask me something and the word “Black” came halfway out of her mouth and then she got red in the face. I said, “Wendy, the word is Black! It’s alright to say that.” That’s when I told her, “You have to be able to ask me anything. You can’t walk on eggshells. That way, we can be truthful with each other.”

Bulletin: Were there moments when it was clear that there was something Wendy was missing or something that you needed to add to make it a richer or more accurate story?

Norman: Wendy’s wedding day. I traveled there especially, because her mother said she couldn’t cope unless I was there. Wendy thought I was there [in the church and at the reception]. The wedding was in 1964. Although her parents’ attitude toward me had changed some, it had not changed so much at that particular time that they would have had me come to the wedding. I helped Wendy prepare, but during the wedding I went back to the house. I walked back at the reception time and stood outside. I saw them come out when the rice was thrown and they drove away with the cans on their car.

Sanford: I could almost have told you where Mary sat in the church and what she was wearing. I could picture her at the reception. I could see her at a table at the back of the room. I could picture her dress. Falsely remembering Mary at my wedding kept me from having to face the fact that I hadn’t invited her to come.

Bulletin: Mary, what did it feel like when you realized that Wendy thought you were at the wedding?

Norman: We were sitting on the sofa in New Jersey when she said that! I don’t even know how it came up, but she said, “And you were at my wedding.” And I looked at her and said, “What? No I wasn’t! What’s wrong with you?” I think that is exactly what I said. Wendy asked, “I didn’t invite you?” I said, “No, you didn’t invite me. Do you really think your parents would have wanted me there?” At that time, I’m sure they wouldn’t have. Even the workers at the reception were white. It didn’t upset me that Wendy didn’t remember. It just surprised me that she thought I was there.

Sanford: I was just in a bubble. I was in a dream. When that conversation happened, it sent me to do so much reflection and to realize how white people really do remember things how we want to remember them. I didn’t remember the racism of the time. I started reading and reading and reading. My devotional reading became all about educating myself about why I wouldn’t have remembered it accurately. What did that mean about whether Mary was really my friend at the time? [To Mary:] My mom used to call you her friend. But then you would eat in separate rooms when you were the only two people in the house.

Bulletin: Wendy, in the 1970s, you began to pursue Quaker community and worship and then a ministry degree from Harvard Divinity School. You studied theology and ethics, including with the Womanist theologian the Reverend Dr. Katie Geneva Cannon. How did these experiences impact you and your relationship with Mary?

Sanford: Rev. Dr. Katie Cannon came to HDS as part of the Women’s Studies in Religion Program that brought so many amazing people to campus back then. She was the first Black woman to be ordained by the Presbyterian Church. She ran a wonderful class. I had graduated by then, but my spouse, Polly, was at Harvard Divinity School in the Teaching as Ministry program. I audited Dr. Cannon’s class. She taught ethics through the novels of African American women, teaching about making a way out of no way and standing up for justice and love in impossible situations. Who knows whether studying those books helped me see Mary differently, or if loving Mary made me look at those books more avidly. Then, when I went to see Mary in the summertime, I would bring her the most recent books that Dr. Cannon had introduced me to, and we talked about them.

Norman: I remember The Bluest Eye2 and Audre Lorde.

Sanford: And we read Coming of Age in Mississippi3 together.

Norman: Wendy would want to know if my life was in any way similar to what the books were about. Well, yes. Some of them, absolutely. When I grew up in Virginia, it was white only and colored only. I lived through all of that.

Bulletin: Was Wendy the first white person you talked with about these memories?

Norman: Oh, yes, yes, absolutely. At first I would think to myself, “Why does she want to know this stuff? She is so nosy!” In the beginning, I would just tell her little things. But she was so persistent and her attitude toward me was loving. I started opening up and really talking to her.

Sanford: And then you suggested we write a book.

Norman: We hope that maybe people will read it and will share it with their friends and maybe even see a person of a different race in a different light.

Sanford: I remember you said to me, this book will show people what the supposedly “good old days” were really like. I just hoped that by being cringeworthily transparent about my microaggressions and misunderstandings, other white people might read it and notice things in this book that they hadn’t been aware of. I tried to be really honest about what I’ve learned. There are biases that “good white liberals” don’t understand that they have. I also wanted the book to be trustworthy to readers of color. Not that I had anything to teach them at all, but I wanted it to be trustworthy.

Bulletin: Are you still able to keep in touch regularly? What does your relationship look like now?4

Sanford: Mary and I text or speak every week or so. We are blessed to be able to stay in touch. During the first year of the pandemic, we were in contact daily as a way of helping each other through the uncertainty and fear. During the insurrection on January 6, 2021, we called each other in horror. This June, my spouse, Polly, and I were able to drive to Virginia to spend three nights with Mary for the first time since the pandemic. Long hugs, long talks, a lot of joy. Meanwhile, Mary and I have been speaking with groups—book groups, social justice groups, church groups—via Zoom. At each talk, we seem to learn something new about the other person. Our relationship is evolving in ways we hadn’t even expected.

Notes:

- Boston Women’s Health Book Collective, Our Bodies, Ourselves (Simon & Schuster, 2011). Wendy Sanford is a founding member of the Boston Women’s Health Book Collective. In 1971, they published Our Bodies, Ourselves, a revolutionary text about women’s health, sexuality, and relationships. It was revised and updated eight times between 1971 and 2011. This work continues with Our Bodies Ourselves Today (ourbodiesourselves.com), a collaboration of the Center for Women’s Health and Human Rights at Suffolk University and the nonprofit organization Our Bodies Ourselves.

- Toni Morrison, The Bluest Eye (Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1970).

- Anne Moody, Coming of Age in Mississippi: The Classic Autobiography of Growing Up Poor and Black in the Rural South (Doubleday, 1968).

- Recovering from COVID at the time of this question, Mary asked Wendy to respond.

Eva Seligman, MDiv ’22, was a high school teacher before she came to HDS to study the entanglement of Buddhism and colonialism. She now lives in Chicago, where she works at the Holocaust Educational Foundation of Northwestern University and as an Executive Function Coach.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.