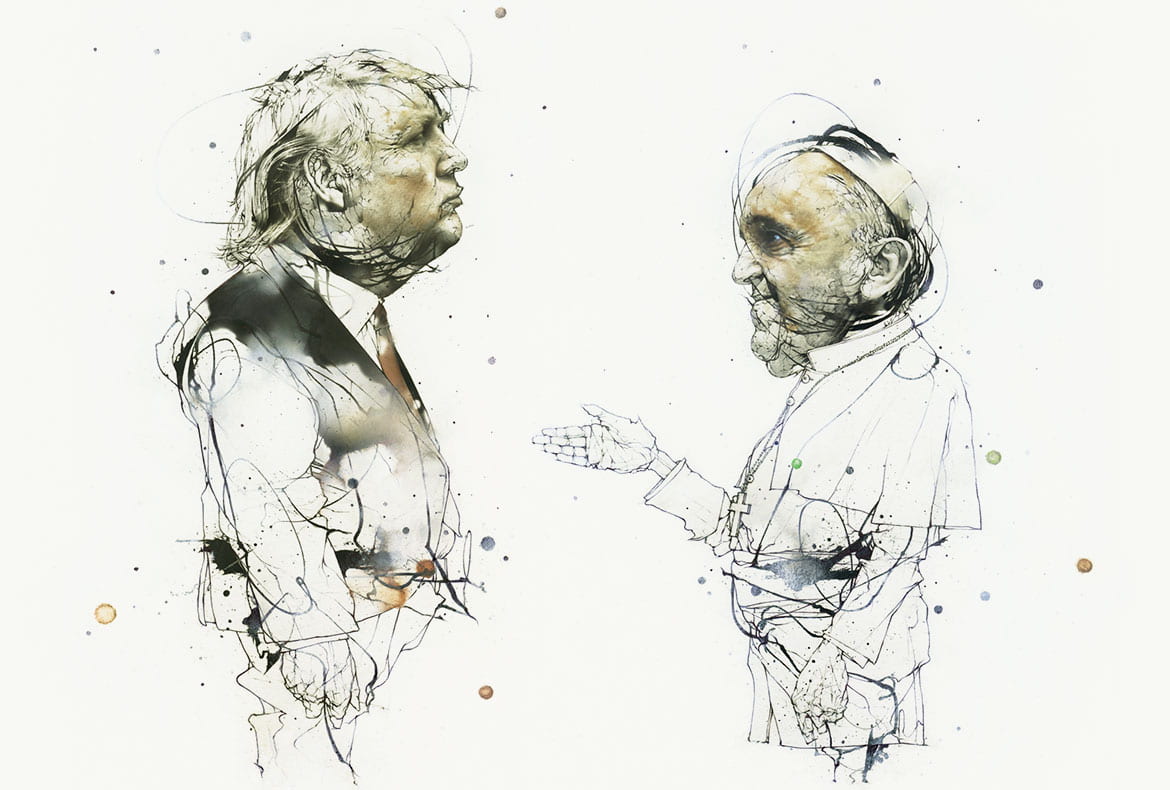

Dialogue

Trump & the Pope: ‘I’ vs. ‘We’ Visions

Illustration by Andrew Zbihlyj

By E. J. Dionne and Catherine Brekus

As part of the Dean’s Leadership Forum at Harvard Divinity School held on April 8, 2016, Washington Post columnist E. J. Dionne gave prepared comments on the current election campaign and then engaged in a conversation with HDS professor Catherine Brekus. What follows is an edited excerpt from that dialogue.

E. J. Dionne: Even before the public fight between Donald Trump and Pope Francis, I was fascinated by the role Pope Francis is playing in this election campaign. Just this morning, two things were announced. One is that Bernie Sanders is going to the Vatican to speak at the Pontifical Academy of Social Sciences next week. Try to imagine a Democratic presidential candidate over the last twenty or thirty years being invited to the Vatican in the middle of a campaign, and it’s a Jewish socialist Democratic presidential candidate at that! This is an extraordinary thing. Also today, the pope released a groundbreaking document called “The Joy of Love.” And while the pope did not change the Church’s formal teachings on gay marriage and other issues, I think it clearly is a move toward what can only be called a more liberal—some might even say modernist—view of sexuality. This remarkable document lays heavy emphasis on personal conscience and is welcoming of everyone into the Church. It is one of many signals that Pope Francis has sent about his desire to minimize the Church’s role in the culture wars, and to reemphasize Roman Catholic teachings on poverty, economic injustice, immigration, and the plight of refugees. Sanders himself noted that Pope Francis is to his left on many economic questions.

It’s important to recognize that Pope Francis isn’t inventing something altogether new but is restoring an emphasis that has always been there in Catholic social teaching.1 For me, one of the interesting questions is: What will Pope Francis’s impact be as this campaign goes forward? It’s striking that the two candidates who like to quote Pope Francis the most are the two Democratic candidates. You don’t find Republican candidates in this campaign quoting Pope Francis much. This would not have been the case a few years ago.

Moreover, Pope Francis’s early appointments are very much from the progressive tradition in the Church. The new bishop of San Diego is Robert McElroy, who got a PhD in political science from Stanford, and the pope’s first major appointment in the United States was to name the inclusive, collaborative Bishop Blase J. Cupich as the ninth archbishop of Chicago. How much will the Catholic hierarchy, which is still quite conservative, be changed by appointments like these?

So on Pope Francis’s side, you have a reemphasis of Catholicism’s—but also the broader Christianity’s—commitment to social justice. You have an internationalization of the Christian vision, with his emphasis on refugees, on immigrants, and on global poverty. This is a radical change from what we have been accustomed to over the last several years, and it could shake up this campaign in interesting ways.

On the Republican side, Trump has also shaken up the religious conversation. Since the late 1970s to early 1980s, we’ve had one notion of white evangelical Christian conservative politics in our head. I always say white because it’s important to remember that the vast majority of African Americans are definitionally evangelical Christians, but they are not notoriously conservative in their views on social or economic justice issues. One of the fascinating things the polling reveals is that African Americans are quite close to white evangelical conservatives on many theological questions. And yet the preaching in their churches is quite different. You hear a lot more Exodus in the African American church. You hear a lot more Micah and Amos and Isaiah. You can still hear Martin Luther King’s invocations of Amos, “Let justice roll down like water and righteousness like the mighty stream.” In most white evangelical churches, you do not have that same prophetic emphasis.

What Trump has done among white evangelicals is to create a real split. Some evangelicals have been extremely critical of him, including Russell Moore.2 In a piece Moore wrote for the National Review, he asked if conservatives can really believe that, if elected, Trump would care about protecting the family’s place in society, when his own life is unapologetically what conservatives used to recognize as decadent. He also asked, how can we really be comfortable with a guy who’s made a lot of money off of gambling? He added that Trump’s willingness to ban Muslims, even temporarily, from entering the country simply because of their religious affiliation would make Jefferson spin in his grave. Yet despite these denunciations from many key conservative evangelical leaders, Trump has done very well among evangelical voters in many primaries, picking up a serious share of the evangelical vote, particularly in parts of the deep south.3

I think it’s important to try to understand what might be happening here. Robert P. Jones of the Public Religion Research Institute suggested that many evangelicals are now nostalgia voters, animated less by a checklist of culture war issues or an appeal to shared religious identity, and moved instead by anger and anxiety that grows from a sense that the dominant culture is moving away from their worldview. One way to cast the issue, though it oversimplifies it a bit, is that some evangelicals are still voting on what they perceive as religious and moral issues and others are voting in a much more tribal way, defending their group.4

Indeed, the backlash around race and immigration that motivates a significant part of the Trump vote reminds me of an important historical fact, which is that many white evangelical Christians, particularly in the South, began moving to the right and to the Republican Party in response to civil rights in the 1960s. This split between the tribal versus the religious evangelicals is instructive about something happening in our politics.

One other point: My view is that the way in which Hillary Clinton is most likely to solve her authenticity problem is if she becomes far more out front and embracing of her Methodist faith and its social demands. I believe that the old social Methodist in her is a deeply authentic Hillary Clinton, but it is something that her campaign hasn’t conveyed very much. When she quotes John Wesley out on the campaign trail, she seems to light up, and I think voters notice that.

So we have an election where the evangelical movement is split, where the Democratic front-runner may find salvation through public engagement with religion, and where a Jewish socialist is heading off to the Vatican to make a case about climate change and social justice that is quite congenial to Pope Francis’s worldview. In American politics right now, religion is working in mysterious ways!

Catherine Brekus: This truly is a fascinating moment in terms of the influence of religion in politics. I’d like to hear you talk more about the two opposite tendencies you identify, with Pope Francis and Trump pulling the electorate in such different directions. Trump seems to me to be a sort of caricature of American individualism. He’s the cowboy who’s self-reliant. He comes in and gets things done. He’s the autonomous individual. The Catholic Church, as you know, has had a long history of suspicion of that kind of individualism and has been focused much more on the common good. So it seems to me that right now we have two models of human flourishing, one in which Trump says the way to make the world better is to get rid of any restrictions on individual freedom, and another coming from the pope and other social justice advocates suggesting that we need some limitations on human freedom and individualism for human flourishing.

Dionne: I will resist the temptation to defend cowboys from being compared to Donald Trump, but that is a wonderful question. I agree heartily that Americans are, and have been from the beginning of the Republic, deeply divided between our devotion to individualism and our deep affection for community. I wrote a book, Our Divided Political Heart, about exactly this. But it isn’t just that we have a communitarian camp and an individualistic camp. I think this division goes right down the middle of so many of us who are American. You even see it in the Declaration of Independence. The beginning is about life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness—about individual rights—but at the end, the founders pledged their lives, their fortune, and their sacred honor, realizing that these goals can only be achieved through common action. I always love to ask people: What is the first word of the US Constitution? I like to hear what the answer sounds like. So let’s do it: What is the first word?

Audience: We!

Dionne: Exactly. We don’t say it enough in our country right now, but it’s an extraordinary fact about our Constitution. “We the People” is often used as a slogan on behalf of whatever kind of politics you have, particularly by the Tea Party, but it’s a “we” document, right at the beginning. And those are collective goals in the preamble.

This split runs deep in us. Paul Begala, the Democratic strategist and political contributor for CNN, once wonderfully described two streams of rhetoric that always worked in Texas politics. Stream one is: We came down here on our own. It was a wild land. It was a mess. In some cases, they might say we fought off the Indians. In some cases they might not say that. But the gist is that we built this by ourselves and we are self-reliant, and other people should be, too. That speech works. But then he points out the other speech or stream that works: We came down here in wagon trains. We stuck together. We protected each other. We showed up in a community. The first thing we did was to build a church, and the second thing we did was build a school. And we made it together because we stuck together and stood up for each other. Those are two very different American frames.

What’s peculiar about Trump is that, in many ways, he has brought to our shores a kind of right-wing European nationalist politics. There’s a “we” in Trump, but it’s a much more restricted “we.” It’s the “we” of economic nationalism. Trump made that famous comment in one of his speeches—“I love the poorly educated”—and I think we need to remember that those with less formal education in our society have been crushed economically. Two kinds of people are always pitted against each other in politics who we should work to bring together—older, white working-class people, particularly men; and African Americans in the inner city. William J. Wilson wrote a book, When Work Disappears, about the cost of deindustrialization in the inner city, which has devastated both of these groups. Nonetheless, Trump’s explanations are nationalistic, they’re exclusionary, and that rhetoric—rightly so—offends those of us who, in a broad sense, are liberal. I think of myself as a communitarian liberal in my politics, or a social Democrat, and I don’t appreciate this kind of exclusionary rhetoric.

Brekus: There is a “we” in Trump, but it’s a racially inflected “we,” and I think it’s also a class inflected “we,” whereas I think Pope Francis is trying to create an image of human flourishing in which we have a preferential option for the poor. It’s hard to imagine Trump accepting any of that language.

Dionne: Yes. I was trying to think what Pope Francis’s slogan would be in this campaign if he were running for president. And one of the slogans that came to mind was “stronger together.” This is at the heart of Pope Francis’s view. On the one hand, he can be very critical of rich people and rich countries for a lack of generosity, which is probably why he’d do very badly in an American election. He wouldn’t get much Super PAC money! But in his speeches in the United States, there is the message that all of us are better off if all of us are better off, and that we are all implicated in each other. That is a very different kind of argument.

Brekus: When I was reading the pope’s Laudato Si document, I used my computer to count how many times he used the words “common good.” And it was more than thirty times. This was also true in the pope’s address to Congress, so Trump’s “Make America Great Again” wouldn’t square with this vision of the common good for everybody.

Dionne: By the way, Trump critics have put out competing baseball hats that say “America is already great.” I find it odd that progressives can sound more patriotic these days than conservatives! There is such pessimism about the United States, that we’re going to hell in a handbasket in terms of our values, that becoming a much more diverse country is a negative because some people are not accustomed to it. So I’ve been saying that what conservatives need to discover is what Sarah Palin called the hopey-changey thing. I do think that conservatism, at its most successful, has had a strong element of hope in it. And I think that conservatives need to be more comfortable with what America’s becoming. Some are, but a lot aren’t.

Brekus: When you try to figure out Trump’s religious background, it is somewhat murky, but what he points to himself is that he went to Norman Vincent Peale’s church as a child. He was married for the first time in Peale’s church. Of course, Peale wrote The Power of Positive Thinking, published in 1952. And in some ways you can hear Peale’s influence in Trump, where you have to think positive and never, ever accept defeat. But at the same time, Trump does sound deeply pessimistic sometimes about America and what the future might look like. Going back to Peale, this raises the question about why Christian voters are willing to support him.

My sense is that some of this has been overblown. Some of the polling has suggested that people who go to church once a week actually are pretty negative about Trump, including evangelicals.5 A lot of people self-identify as evangelicals, but it’s not clear to me always what that means. If you get down to the level of practice, church-going Christians seem somewhat suspicious of him. But the narrative in the larger culture—and this is partially because of Jerry Falwell, Jr., who very publicly endorsed Trump—has been that evangelicals are among his main supporters. What are your thoughts about this?

Dionne: What you say is important and true: as best as we can tell so far, the more church-going and religiously engaged evangelicals are less pro-Trump. It’s one reason why Ted Cruz did so well in Iowa. One of my favorite journeys so far in the campaign was to this wonderful little town called Keosauqua, Iowa, on the Missouri border. About one hundred to one hundred fifty people were gathered in a storefront to hear Cruz, and at the end of his speech, he looked at the crowd and said, “Awaken the body of Christ!” This was in a political speech. He got a real response from this crowd, which was heavily evangelical, and those kinds of evangelicals supported Cruz over Trump.

I also think there’s a clear class split among evangelicals, as there is through the whole Republican electorate—college-educated evangelicals are less pro-Trump than non-college educated ones. And there has been some evidence that people who go to prosperity or health-and-wealth churches—however you want to characterize them—may be somewhat more inclined to vote for Trump than other evangelicals are. I don’t think we have enough data to support this, but it has an intuitive sense to it.

But I also believe that we have, in a way, overemphasized the role of moral issues in the white evangelical vote during a period of fifty years. Again, a lot of these voters started voting Republican with Barry Goldwater in 1964, because of his opposition to civil rights bills (on State’s rights and property rights grounds). That allied Goldwater with white southerners who opposed civil rights, and those factors continue to play out. Whenever we talk about race, we have to be very careful. It would be wrong to say that this is all about race, but it’s equally wrong to say that it has nothing to do with race. You can’t wash that history away, and I think Trump is exposing some of it. It’s been said that many conservative politicians have used a dog whistle on these issues, and Trump uses a bullhorn. There may be something positive about putting all of this stuff out on the table so we can talk about it, as long as he doesn’t become the enabler of a kind of public racism that is very destructive.

Recently, on my book tour for Why the Right Went Wrong, I was in Louisville, Kentucky. An Indian American woman stood up and told a story about her son, ten or so years old, who was asked by a kid in his class, “Are you Muslim?” Her son said, “No, I’m Hindu.” And then he got invited to a birthday party. The woman said, “I wonder, would he have been invited to that birthday if he had answered, ‘I’m a Muslim’?” And then she talked about whether we are enabling a kind of discourse all the way down that encourages people in this direction. It’s something to think about. The negative would be if Trump’s rhetoric and the way he is exposing political motivations makes people feel it’s okay to exclude a ten-year-old kid.

Notes:

- In the 1980s, the Catholic bishops issued two pastoral letters: one on economic justice that was very critical of the workings of the capitalist system, along lines that Pope Francis would recognize; and another on nuclear war that called for war always to be a last resort, setting up very strict criteria for warfare.

- Moore is the president of the Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission of the Southern Baptist Convention.

- To give some numbers from two states: Evangelicals made up 77% of Alabama’s Republican primary electorate, and Trump carried the evangelicals 43 to 23% over Ted Cruz. Among non-evangelicals, he beat Cruz by 41 to 18%. In Wisconsin, where he lost again, there was no big difference between evangelicals and non-evangelicals: 34% of evangelicals, 36% of non-evangelicals.

- Another interesting analysis is Elizabeth Bruenig, “How Ted Cruz Lost the Evangelical Vote,” The New Republic, February 24, 2016.

- See Geoffrey Layman, “Where is Trump’s Evangelical Base? Not in Church,” The Washington Post, March 29, 2016.

E. J. Dionne is a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, a syndicated columnist for The Washington Post, and a university professor at Georgetown University. He is the author of six books. The most recent is Why the Right Went Wrong: Conservatism—From Goldwater to Trump and Beyond (Simon & Schuster, 2016).

Catherine Brekus is Charles Warren Professor of the History of Religion in America at Harvard Divinity School and in the Department of American Studies at Harvard University. She is the author of many articles and books, including Sarah Osborn’s World: The Rise of Evangelical Christianity in Early America (Yale University Press, 2013).

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.