Dialogue

The Underside of Globalization

Growing up a “street kid” in Juarez, Mexico, was like being a lab rat in a socioeconomic experiment with terrible consequences, especially for vulnerable children.

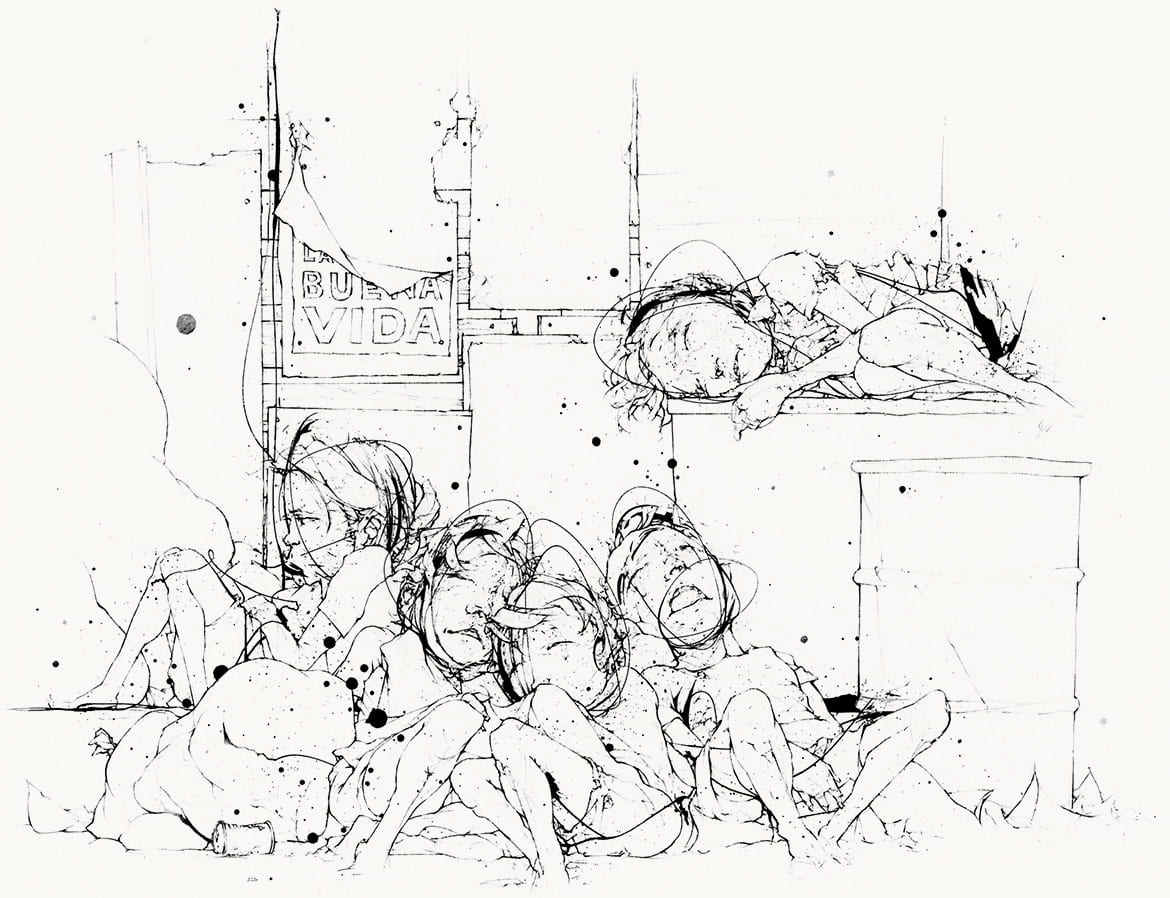

Illustration by Andrew Zbihlyj

By Pedro Morales

A safe place to sleep was essential for surviving the streets of the west side of Juarez. Knowing well the dangers of the street life for a ten-year-old, I carefully selected my places to lie down at night and equipped myself with water, canned food, and a blanket or enough newspapers to sleep on. I had three such spots. The first was a junkyard nestled at the top of a small dusty hill overlooking the rugged borderland landscape. There, I dug a hole under a compressed beetle-green Impala and slept in it when it rained or when things were hot in the neighborhood. From my hideout I felt the unmistakable, oppressive force of the muddy current of the Rio Bravo, the river which divides Juarez, Mexico, from El Paso, Texas. The river was enclosed by a cement causeway and barbed-wire fencing. It felt like a ferocious beast reminding us to stay south of the dividing line, where we were constantly watched by the U.S. Border Patrol.

A second, if more exposed, place was the rooftop of the house where my mother and siblings lived a few short blocks from the river. I would use this place only on holidays, weather permitting, so I could feel part of the family gatherings without risking beatings. The last space was under wooden fruit and vegetable display stands in the marketplace behind the Catedral de Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe, on the south side of the Calle Mariscal. Here, the cathedral, the old city hall, the marketplace, and the whorehouses stood only yards from each other, making it the crossroad between the sacred and the profane. The emerging trend toward economic globalization had already left large numbers of Juarez’s children without adult supervision and exposed to violence, often from predatory relatives. Like most kids I knew, by the time I was ten years old in the mid-1980s, most of my time was spent on the streets, particularly the Calle Mariscal: my home.

Although NAFTA was approved in the early 1990s, the emerging large-scale trade with the United States and Canada had begun to transform our sleepy and forgotten border town at least a decade before, when politicians and big businessmen agreed that the best way to help the poor was to take away all public spending for the west side of Juarez. Money for community policing, transit, utilities, schools, and street repairs was redirected toward development on the east side so as to make it ready for the promised foreign direct investment expected under the looming trade agreement between Mexico and its northern neighbors.

The lure of employment was real. The increased presence of industrial factories (maquiladoras) quickly absorbed, like a gargantuan mouth, the adults from the wretched homes on the west side: first the mothers, and then however many fathers were left. Soon uncles, aunts, grandmothers, grandfathers, and any other person who traditionally helped to look after children worked at least one if not two jobs. The absence of safe adult supervision created an enormous vacuum for hundreds—if not thousands—of us kids. My mother, a single parent in her early twenties with four children, was one of those young women lured to the maquila, where she worked double shifts putting transistors in television sets. For my siblings and me, her absence meant sexual abuse and sadistic violence from relatives and family acquaintances. So much so that, as bad as the streets could be, I felt I had a better chance of surviving there than in my own house. We never understood fully the root causes of our plight, nor could we have foreseen the future of exacerbated violence and lawlessness being forged for our communities by the misguided polices of the U.S. and Mexican governments and the transnational corporations. A large-scale socioeconomic experiment was performed on us—like lab mice—with terrible consequences, particularly for the most vulnerable: children of single mothers.

The job bonanza was great at first. However, the family support system was quickly sucked into the new industry. Many workers took double shifts, hoping to take advantage of a larger payday. This meant even less parental presence at home. The demand for workers was so great that people started to come to Juarez from nearby cities and towns. In the decade between 1980 and 1990, the population surged from 544,496 to 789,522. People arrived from Ojinaga, Agauaprierta, Parral, Casas Grandes, and Chihuahua City; by the mid-1980s, people were coming from places further south, like Durango, Zacatecas, Edo de Mexico Tlaxcala, Coahuila, and Veracruz.

As it turned out, the factory salaries were never that great for low-level workers, and the economic expansion also drew people involved in sex, drug, and weapons trafficking. The migrant-smuggling industry boomed in Juarez, with the downtown area providing the critical infrastructure and labor required for the increased demand. At the street level, one could see strangers arriving nightly at the cantinas and pulquerias (watering holes) and people asking for handouts after arriving at the bus and train terminals. Women and children lined up at church doors to request shelter and food assistance. More and more apartments served as temporary houses to hold would-be migrants to the United States. People rented out their homes and used their vehicles to help traffickers move people and products. Soon, many locals were associated at one level or another with the emerging shadowy market, either as workers or as part of the criminal infrastructure—or, like most members of the police, playing both sides of the law.

Soon gangs were everywhere, their turfs shifting shape constantly, which made it very hard for those not in the know to get past certain hot spots, particularly closer to the international border, since control of the bridges was the name of the game. Juarez was in a bloody war, with countless casualties, long before the drug wars and murders of local women became international news, and most of the victims were poor, displaced, disposable people.

When i was growing up, the key question you had to know how to answer was “¿Que Barrio?” Meaning, what neighborhood do you live in? What’s your turf? The question was important because it revealed whether you knew who ruled the area you happened to be walking through. During my childhood, the most fearsome local gang was El Puente Negro (the Black Bridge Gang), notorious for distributing narcotics and gathering intelligence for smuggling operations. They would instruct their people on how to answer ¿que barrio? If you did not know the answer, you’d best start running—preferably toward a rival territory. For us young kids who had no real gang affiliation, this was a nightmare. No affiliation meant more mobility, which was vital to me, but it also made me vulnerable to attacks from all sides, at any time and without reason or warning. I could easily spend a whole afternoon running from one rival gang territory to another. Most kids would affiliate with street gangs, seeking safety in numbers and a sense of belonging at the price of being bound to a specific number of city blocks and chained to a never-ending war.

But I wanted none of it.

From the age of ten, I often worked until late at night in the Calle Mariscal’s brothels, passing messages between the gangsters who gathered there and their network of people throughout the city. The messages were always short and encrypted. I would be instructed to say something like “Move at 8 pm, what you need will be waiting there” to a man in charge of a holding house. When I delivered the message, a coin worth five or ten pesos would hit the palm of my hand. Then, I would run back to report on the mission and another coin would usually reach my pocket.

By the time I came back to the marketplace, around 2 am, I had no chance of finding a decent place to sleep. I learned a clever way to arrange piles of flattened cardboard boxes between the exposed lower parts of the fruit stands and the trash barrels. I would also line the sidewalk under the stands with the same material to make room for some of my friends. A second problem I faced was how to avoid the kids, mostly preteens, who were addicted to smelling glue, many of whom I knew. The stench of dendrite hovered over all of us and was worsened by the combined smells of urine, rotten food, and fumes from the diesel trucks and buses. I had to fight back the feeling of disgust the daily scene provoked in me.

The very first time I was offered a sniff was right after I witnessed what this drug did to Ilario, aka El Greñas. A year or two younger than me, Ilario was new to the street scene, and I had become friends with him. When he tried his first sniff, he vomited and gasped. This was followed by a panicked look as he hit the floor with a thud. He kicked his legs amid the laughter and mocking of the fifteen or so onlookers. Ilario was turning blue when he was helped up by two of the older boys. They moved his arms up and down for a minute or so and encouraged him to breathe through his nose. They said his throat was swollen, which often happened to the inexperienced.

When they looked at me and said it was my turn, I declined. The hostility was immediate. The main instigator was a kid known as El Gato, who was four inches taller than me and at least twenty pounds heavier. Knowing I could not afford to look weak, I launched at him without warning. My attack was sudden and merciless, like a panther jumping after its prey. I punched his eyes and nose. The screams and cheers from the audience grew louder and louder as blood begun to appear on El Gato’s face. I knew I had to stop, but I couldn’t. Suddenly I had a target for all my rage and pain. Then, someone hit me on the head with a rock from behind, triggering an all-out fight among those present. The sight of my own blood snapped me back to awareness, when Chucho, the eldest among us, called for everyone to stop. The pungent smell of glue, spilling from plastic containers and aluminum cans, enveloped the scene.

Looking back, I know I did not want to teach El Gato a lesson. I wanted to destroy him, or rather, I wanted to destroy myself. I saw myself in him and I wanted to do away with what I had become: A street kid. A child no one ever wanted or cared about. A mistake. A crude reflection of a merciless society rushing stupidly into shortsighted “pro-growth” polices with no concern for children like us. Reduced to street rats, we ate rotten food, learned to hate each other, and sniffed glue to numb our hunger, our pain, and our fear. This is the side of economic growth and globalization that bankers and politicians coldly label “externalities.” That’s all we were then, and that’s all we are now, on the Calle Mariscal.

Pedro Morales is a recent graduate of the MTS program at Harvard Divinity School. He has been an activist in East Boston for eleven years, and is currently at work on a book of short stories about his childhood in Juarez, Mexico.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.