In Review

The Democratic Dilemma

Religion and politics, then and now.

By Todd Shy

Writing in the 1920s, as the first wave of fundamentalism swelled in America, Walter Lippmann was sympathetic to the contemporary believer’s dilemma. His book A Preface to Morals, remarkably engaging 80 years on, described how the “acids of modernity” had eroded not the capacity for religious experience itself but the ideas that gave them shape. “If faith is to flour-ish,” he wrote, “there must be a conception of how the universe is governed to sup-port it.” Post-Darwin, post-Einstein, post-Hubble (post-Romanov) religion itself was not, of course, rendered impossible, and yet traditional views of an authoritative God were not easily harmonized with a world of adaptation, relativity, and radical egalitarianism. Lippmann saw a kind of stalemate: “It is impossible to reconstruct an enduring orthodoxy, and impossible to live well without the satisfactions which an orthodoxy would provide.”

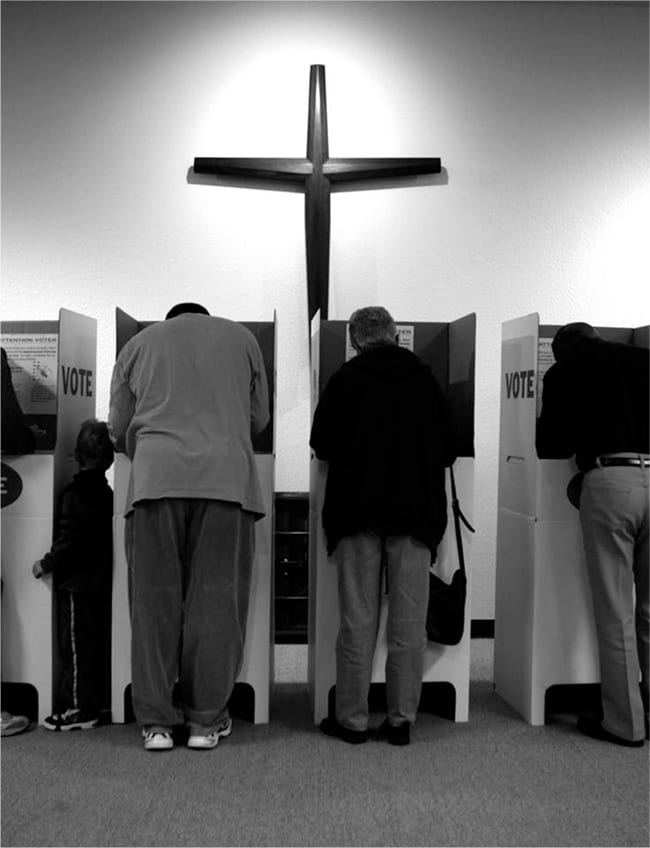

Conservative Christians today hedge the dilemma Lippmann described by claiming that the democratic order either remains somehow a godly order (America as a Christian nation), or is at least securely under God’s ultimate rule. For religious conservatives, America might be a democracy, but the universe remains a monarchy, and the supposed rupture of modern knowledge is just one more upstart rebel-lion destined to be absorbed into higher meaning or defeated outright. Regardless, there is an unchanging order, and we are located in that order.

Could it be that religious belief is either inherently conservative in style or else resistant to politics?

But now prominent liberals, burned at the polls in 2004, bouncing back to their toes in 2006, are insisting that while conservatives have the wrong policies, the impulse to draw biblical morality into modern debates is right. Strong voices on the left are telling us that to govern ourselves we need reminders of how the cosmos is governed. Both Democratic frontrunners for the next presidential election, Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton, have, for example, spoken about the need to infuse policy discussions with religious values and explicitly religious rhetoric. This strategy concedes that fundamentalists have been wrong in substance but right in style, that the way forward for progressives is to articulate a better religious-based morality rather than to insist that the relationship between religion and politics steer a different course. I don’t know that this can’t be done well. Still, it has the whiff of a quest for a kind of constitutional monarchy on the grand scale, whose advocates seem nostalgic, like conservatives, for the vanished kind of world Lippmann described, a world in which “the government of human affairs is a subordinate part of a divine government presided over by God the King.” Is it that religious belief, in the end—not the tenets but the experience itself, the piety, the instinct—is either inherently conservative in style, or else resistant to politics, period?

Powerful attempts have been made to show that liberalism has a values-shaped hole that only spirituality can fill. Jim Wallis’s best-selling God’s Politics: Why the Right Gets It Wrong and the Left Doesn’t Get It may be the bible of the religious liberal adjustment. Written in the wake of the 2004 election, Wallis called on progressive Christians to resist allowing “the right to decide what is a religious issue.” For decades Wallis has worked to help poor communities and to engage larger political debates through his magazine, Sojourners. Both Obama and Clinton have spoken at a Sojourners conference. Wallis is an evangelical, drawing his faith and his theology from the Bible, but he is an evangelical with an unapologetic social conscience, and he has tirelessly rebuked fellow evangelicals for years for their narrow reading of scripture. In God’s Politics, he presses Democrats to see the benefits of taking religion seriously:

. . . there is little question now that the Democratic Party should move much more deliberately to embrace religious communities and concerns, to use moral and religious language to argue for social reform, and to learn from the lessons of progressive movements in American his-tory as they advance their agenda for the future. In large part, the desire to affirm progressive religion is coming from spiritually devout Democratic elected officials, who feel they have been religiously disrespected not only by Republicans but even by those from within their own political ranks.

In this regard, Wallis suggests, conservatives are right: Democrats don’t know how to talk about faith, and so they ignore something of tremendous importance to voters. But Wallis thinks conservatives have distorted the gospel by obsessing over a narrow range of largely sexual issues and ignoring the larger calls of justice, compassion, and peace. With powerful, simple eloquence, Wallis rebukes a nation so affluent and seemingly pious, in which one out of every six children is poor and 45 million citizens lack health insurance. More than any other evangelical, Wallis has worked to have progressive causes be treated as pressing moral issues, and in this way, as he acknowledges, he is, at heart, “a nineteenth-century evangelical.”

A Preface to Morals

Throughout God’s Politics Wallis points to the antislavery movement and to Martin Luther King, Jr., as examples of religion providing moral guidance on issues of national concern. Something akin to the prophetic power of King’s pronouncements about inequality are what Wallis clearly wants for problems of poverty, global peace, environmental devastation, and overall economic injustice. These are moral issues because they reflect the kind of society we want to be; they embody our unspoken values. And since moral discussions have traditionally drawn on religion, Wallis argues, our moral discussions should continue to do so today.

But while Wallis is unequivocal as a moralist, his attempt to frame policy as a spiritual and theological issue is, despite his urgency, less convincing. “The spiritual component” in politics, he writes, is “absolutely crucial.” And in his view traditional religious commitment is utterly compatible with participation in democracy: “To influence a democratic society, you must win the public debate about why the policies you advocate are better for the common good. That’s the democratic discipline religion has to be under when it brings its faith to the public square.” Senator Obama is even more specific: “Democracy demands that the religiously motivated translate their concerns into universal, rather than religion-specific, values. It requires that their proposals be subject to argument, and amenable to reason.”

This careful balance is a sensible expression of how religion can flourish within a democracy, but it is a narrow path, and Wallis doesn’t always stay on it. What can we make of his later statement, for example, that the “task of securing peace and security requires qualities that are specifically religious,” namely, “the energy of hope”? In what sense is hope specifically religious? Wallis’s hope may be fueled by religion, but surely hope is not inconceivable apart from the aid of the Hebrew prophets. And if hope is the energy we need politically, isn’t it a strange leap to say that we need religious hope because in the past progressive movements have drawn on religion? And if the progressive past is our tutor, wouldn’t we have to note that at precisely the time in our nation’s history when religion had its greatest moral influence, the country’s gravest moral-political disaster erupted regardless, namely, the Civil War?

God’s Politics wants to encourage robust religious influence in the political sphere, but in the end the argument is theologically evasive. If something “specifically religious” is called for, then something theologically clear is required. Conservatives, after all, are unequivocal not just about their policies but about the narrative that makes them believe, and their political commitments are extensions of that faith. But liberals tend to rely on principles rather than narratives, and the conviction seems less personal and more provisional. Where evangelicals, say, love Jesus, liberals celebrate faith journeys. Religious liberals discuss a dynamic of love that makes life wonderfully rich; conservatives go on talking about the object of their love (and allegiance). And while it is interesting to hear Romeo describing his sense of inflation and intoxication, we also want to hear about Juliet. What is it that he loves about her? Why her and no one else? What is it that he glimpses that seems to change him so utterly? Because in the end we don’t want endless exegesis of Romeo’s love, we want our own Juliet. We want our own throats to burn. We want to stand below her balcony and thrill when her hand lifts the shade. Since conservatives talk about God this way, we feel we understand what their God is like. He gets into their spines; he changes how they value the world. The God of God’s Politics, for all Wallis’s obvious piety, is a silhouette theologically. This may be incidental to whether we agree or disagree with Wallis’s political priorities, but it is a significant evasion in a book that wants liberal religion to resonate in the same arena as the religious right. Wallis’s God is the champion of justice and the defender of the poor, but there is nothing about him as compelling as the elusiveness, say, of Luther’s God, or the inscrutability of Job’s. His God is not a God who hides; his Jesus is never bewildering. Wallis offers us the clarion morality of the prophets, but not the shifting range of Old Testament experience. The bound child is pulled away from harm, but no knife has been raised by the godly over the ropes. Biblical writers grope to understand a difficult Creator; Wallis seems content with what he knows. In the end, religion, like our other deep experiences, is disturbing, unsettling, even as it irresistibly holds our devotion. Liberals like Wallis need to engage us on the level of our private shuddering in order to energize our public commitments. After all, the success of religious conservatives is not the raw manipulation of an issue like abortion, but rather the education of congregations to see God as a being who would revolt at the abortion of a fetus. The portrait of God is all. The rest is just elaboration, which is why Augustine’s famous quip, love God and do whatever you want, makes utter sense to the religious conservative, who wouldn’t dream of intentionally abusing it, precisely as Augustine knew.

The critical commitment, then, involves what Lippmann calls “a psychological machinery for enforcing the moral law.” Conservatives nurture this instinctively. Liberals rightfully—thankfully—are more ambivalent. But you can’t simply swap out conservative passion for liberal passion without addressing this theological under-pinning. Again, to use Lippmann’s phrase, the “supporting conceptions” must be there, not just a table of other virtues.

God’s Politics

Wallis acknowledges that personal piety is the basis for moral commitment and admits that conservatives cultivate this more effectively: “liberal religion has lost the experience of a personal God, and that is the primary reason why liberal Christianity is not growing.” But he sets the questions aside as if that were the obvious and easy part. It is not. If what liberal politics needs is an injection of spirituality, Wallis needs to show how that is cultivated, as well as what, politically, it leads to. Instead, he calls liberals to action. In place of a courtship, we are asked to elope. Wallis knows what we need to stand for—the vision is already there, he tells us, in the biblical prophets—we just need to get going. But a moral vision must do more. It needs to earn our attention and tap our “unconscious assumptions,” especially in the wake of Lippmann’s “acids of modernity.” It must instruct our actual instincts and shape what we really love. This requires more than quoting Zechariah.

The great strength of the liberal ideal has been its capacity to encompass modern ambiguities by, to borrow Isaiah Berlin’s phrase, shifting foot to foot, by tolerating movement among our hopes, by honoring multiple goals that are valued even when they are hard to hold together. Acknowledging distance between God and humanity is not a denial of values or a cowardice about faith. Hesitation to say, “This is the truth, we have received it from Amos,” is not a failure of nerve; it is hard-won wis-dom. This shifting from foot to foot has been the virtue of liberalism, and the left should be wary of abandoning it for conservative-style conviction. Wallis and others are writing to chide the failure of liberal conviction, but the connection between political courage and theological boldness is a conservative confusion. To be bold politically is not to understand more about God’s will but, in the absence of policy direction from above, to discover that our best hope is to be just toward each other, to affirm, in Obama’s words, that “we have a stake in one another.” The grip of contingency is the liberal’s gravity. It is the fundamentalist’s style to soar free. Wallis, a tire-less advocate for the poor on the ground, still prefers theological flight.

Rabbi Michael Lerner, editor of Tikkun magazine and author of The Left Hand of God: Taking Back Our Country From the Religious Right, wants to broaden Wallis’s argument. Lerner enjoyed brief prominence in the early Clinton years when both the president and the first lady quoted his language of a “politics of meaning.” Now, in the face of what he sees as a “genuine spiritual crisis in America,” Lerner has turned his attention to building a grassroots net-work of progressives, which, he hopes, reenergized by “love” and “awe,” will even develop new rituals and liturgies for a freshly spiritualized nation. A psychologist by training, Lerner has a vision that is more therapeutic than Wallis’s, and, where Wallis calls himself “at heart a nineteenth-century evangelical,” Lerner is nostalgic for the activist 1960s and 1970s, when, for a “brief historical moment, millions of people allowed themselves to imagine what the world could be if love prevailed and a more authentic existence could be forged.”

The reason it did not last, Lerner asserts, is that the left lacked “spiritual aware-ness,” which created a vacuum of meaning the religious right rushed to fill. Three decades on, Lerner concedes that the religious right has been successful because it has addressed genuine human needs, and to an extent he is eager to imitate their “willingness to state their objectives clearly and honestly, a refreshing change from the diet of mush that often emerges from the Democratic Party.” Throughout the book, Lerner chides the left for “lacking any positive vision,” for its “lack of clarity” and “clearly articulated worldview.”

The Left Hand of God

The worldview Lerner presents to correct this mistake involves two forces inside human beings and in the universe, forces he refers to as Hands of God. People, Lerner writes, “seem to have two voices in their heads, the voice of fear and the voice of hope. The Right Hand and the Left Hand of God.” At times these seem like unfortunate metaphors for love and anger; at other times they are strange stand-ins for divine personality: if there is one God with two dispositions—two hands—we are in the odd position of needing to cultivate the deity’s better side. Regardless, the exhortation to get “more energy into the Left Hand of God” as a key to winning elections is not exactly “I Have a Dream.”

Lerner’s utopia is more broadly spiritual than specifically religious. He thinks progressives need religion because it provides “powerful countervoices to the logic of global capital” and because a “transformative vision of society emerges from a spiritual foundation.” In addition, since 95 percent of Americans believe in God, and 60 per-cent pray once a week, progressives need to address what is, to Lerner, an obvious “hunger for a spiritual connection.” Lerner thinks the religious right understands this hunger for meaning all too well, but that the right nourishes fear instead of hope, irrationality instead of health. This same diagnosis, that people are somehow immobilized without an articulated meaning for their life, is rhetoric that conservative thinkers also use. Religion is staged, then, as an arena for determining meaning.

But it’s not obvious that what conservative religion actually satisfies—or what any religion satisfies—is a longing for meaning. What if, instead, conservative religion thrives on an instinct for order: order for our contrary longings, order for overstimulated imaginations, order in a system whose highest ideal—freedom—by its very open-endedness lays stress on its recipients, order and relief from the psychological responsibility of managing the relentlessness of modern experience, order to protect our children from challenges too great for them, and for us on their behalf? Whatever fuels conservative-style belief, in the most resonant passage in The Left Hand of God, Lerner calls liberals out for dismissing such piety out of hand. It “gives the impression,” he writes, “that one of the most important elements in the lives of ordinary Americans is actually deserving of ridicule.” And, Lerner adds, it doesn’t go unnoticed: “You don’t have to be a genius to know when you are being treated with contempt.”

He’s right; and yet, the very individualistic piety that Lerner criticizes for turning believers away from the common good is, in the end, the secret of conservative religious success. Religion may not be merely private experience, but piety is, and piety is the key to conservative moral commitment. Progressives like Wallis and Lerner want to counter the political impact of the religious right with different policies, but it is not clear what a transformed progressive piety looks like. It is clear, however, what a liberal worldview looks like. Appreciation for the way convictions are shaped by flux is the heart of liberal belief, and it makes liberals hesitant, though not fearful. If liberals look wishy-washy, as they are often accused of being, it is because circumstances constantly shift. When a sailor takes plodding, careful steps on a ship’s deck, no one accuses him of impotence or cowardice. This is how you walk when the sea is swaying beneath you. Liberals need to describe the conditions at sea rather than wishing we were all on land, where conservatives more easily hoist their standards. Liberals, in other words, needn’t imitate conservatives in imagining greater clarity than experience allows, and they needn’t agree that just because there is a shoreline the boat must be docked. There are other shores to get to as well; there are other oceans to cross.

Providing more persuasive descriptions of the conditions we experience is the precondition for winning the debate about solutions. Something like this is what Lippmann does so eloquently in A Preface to Morals. He is considerate of the fundamentalists of his day, but he is more perplexed than they are, and as we read, we’re not sure how the issues will resolve in Lippmann’s own mind. Balancing on that moving deck, he knows the dilemmas of his time are not easy. He knows a great deal is at stake. And he knows that when modern societies extend freedom to individuals, this brings burdens too: “It is all very well to talk about being the captain of your soul,” Lippmann writes. “It is hard, and only a few heroes, saints, and geniuses have been the captains of their souls for any extended period of their lives.” Here Lippmann acknowledges not that the “other side” is asking too much, but that the very ideal he ultimately defends is problematic for most, if not all, people. This is a powerful acknowledgement, because in this way the tension of Lippmann’s vision seems genuine and internalized, and so when he finally articulates his stoical ideal, it may or may not resonate, but it seems honestly achieved.1 In contrast, Lerner and Wallis stand on the far side, calling us to join them. We know what they think from page one. Lippmann, meanwhile, walks at our side. His method—his style—embodies the liberal approach. The argument it-self dramatizes conflict and shifts its way toward its resolution. Liberals have to re-main committed this way stylistically, as well as substantively. Lerner and Wallis know because they know, and in this sense mirror fundamentalists’ style. It is sincere but straightforward. When Lerner calls for “a world in which love and generosity are the foundation of our public life together,” we agree but are not moved. On the other hand, having explored the challenges of birth control and women’s rights in the 1920s, when Lippmann tries to articulate the power that love retains for two people, we know he is trying to do something new and difficult; he is trying to describe the persistence of love in the absence of categories that once framed it. The effort is difficult but urgent, and so the prose itself shudders a little as he describes what modern love can mean without metaphysical reference: two people “desire their worlds in each other, and therefore their love is as interesting as their worlds and their worlds are as interesting as their love.” It is not only that Lippmann is more lyrical than Lerner here, but that the insight is unpredicted and hard won. He is not pressing us to just hold onto the good old ideals; he is pressing himself to describe our ideals in new and interesting ways.

It is obvious that religious commitment continues to play an important and often decisive role in American life, but these calls for believers to take their religion into the public square always miss the vital component, and they miss it necessarily. The vital aspect of religious experience gets left behind because it can never quite translate into policy or rhetoric. This isn’t to say that genuine religion is always mystical, but that all profound experience is elusive—it feels greater than we are, which is why it holds us, and why we find it so incorrigibly interesting and necessary. Like a planet to a sun, we are in its orbit, and you can’t drag the sun where you will. And so those of us who are sympathetic toward even religious experiences that we don’t share know something of what it means to be held by something else, or to be possessed by something that seems expanded around us. This possession could be as common and thrilling as the experience of love. It could also be an insight that, following a raw period of life, brings relief. Sometimes it feels like an idea—it is intellectual. Sometimes it is sentimental—we cry at a song, or a movie, or watching a child run toward a parent. Most often it is relational—we feel reconciled to someone after a period of pain, or we suddenly love someone new. These experiences don’t give shape to our life, they are its atmosphere. We feel that when we’re breathing that air we are where we need to be: we are home. Our other problems and demands remain, but we are in the best place to tackle them. These elusive experiences feel like the conditions for everything else we are. They are, to borrow Chekhov’s word, our secrets. Here, in his description at the end of a well-known story of a man on his way to see his lover, note how beautifully the inward, arguably selfish focus expands out as pro-found empathy, as if cultivating inwardness in the first place is the surest foundation of meaningful bonds:

He spoke and thought that here he was going to a rendezvous, and not a single soul knew of it or probably would ever know. He had two lives: an apparent one, seen and known by all who needed it, filled with conventional truth and conventional deceit, which perfectly resembled the lives of his acquaintances and friends, and an-other that went on in secret. And by some strange coincidence, perhaps an accidental one, everything that he found important, interesting, necessary, in which he was sincere and did not deceive himself, which constituted the core of his life, occurred in secret from others, while everything that made up his lie, his shell, in which he hid in order to conceal the truth—for instance, his work at the bank, his arguments at the club, his “inferior race,” his attending official celebrations with his wife—all this was in full view. And he judged others by himself, did not believe what he saw, and always supposed that every man led his own very real and very interesting life under the cover of secrecy, as under the cover of night. Every personal experience was upheld by a secret, and it was partly for that reason that every cultivated man took such anxious care that his personal secret should be respected.2

Religion affects our public life, but when it strikes truest, it is these secret realms that stir and rumble and soar, which is why religious experience is so resilient, surviving its zealots, and why politics will always include religion in its debates but cannot borrow its authority or mimic its power.

Notes:

- “Yet it is a fact,” Lippmann writes, “and a most arresting one, that in all the great religions, and in all the great moral philosophies from Aristotle to Bernard Shaw, it is taught that one of the conditions of happiness is to renounce some of the satisfactions which men normally crave.”

- Anton Chekhov, “The Lady with the Little Dog,” translated by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky.

Todd Shy reviews books regularly for the News & Observer in Raleigh, North Carolina. His work has also appeared or is forthcoming in Salmagundi, The Southern Review, The Christian Century, and Image: A Journal of the Arts and Religion.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.