Dialogue

On Habit

The habit of playing music for church turns out to be the most important healing practice during a difficult year.

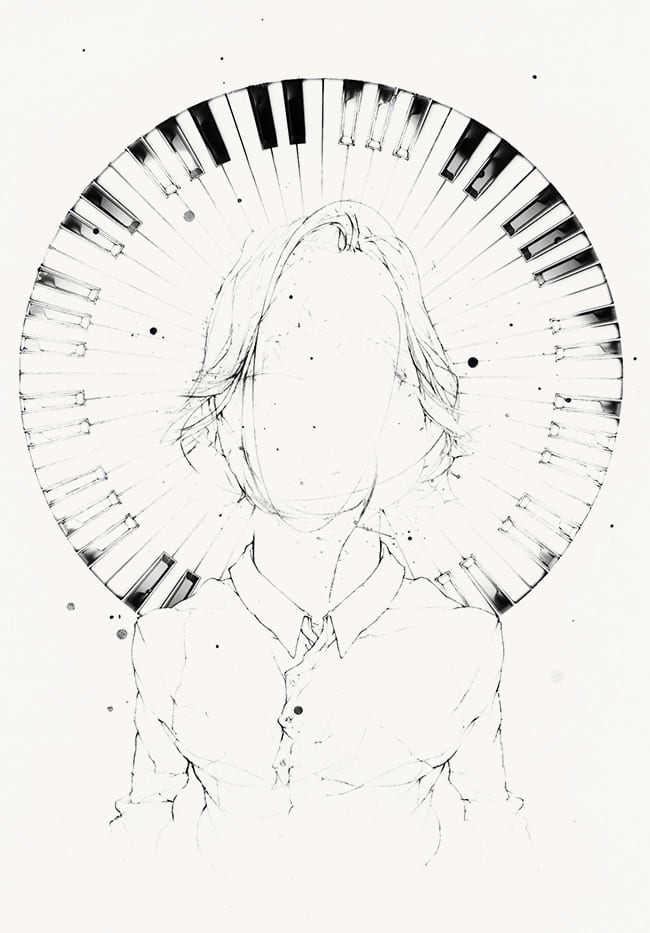

Illustration by Andrew Zbihlyj

By Michelle C. Sanchez

“Is he a saint?” Tarrou asked himself, and answered: “Yes, if saintliness is an aggregate of habits.”

—Albert Camus, The Plague

What is it that makes me who I am? What is it that gives me what I most deeply need?

The authorities who proffer answers to these questions rarely have much to say in praise of habits. By habits, I simply mean the countless things that we do with our bodies on a daily basis, often without consciously engaging big questions of “meaning” or “purpose” at all. Things like walking to the mailbox, taking out the trash, or brushing our teeth. If habits emerge as a topic in contemporary lifestyle discourse, they are often treated as things to be broken or questioned, either because they’re deemed unhealthy or because they might dull a person to her potential for creativity and innovation.

Church occupies a funny place in this modern economy. It’s not really a natural place to go if your goal is to make money or network. But it’s also not merely educational or recreational. To be sure, there are times when church involves any or all of these things. Yet, church seems to lose something—or even become an object of general disdain—when its reason for being is reduced to any one of them.

The increasingly common logic that sees things in terms of monetization and productivity renders church either grotesque or quaint. But I would wager—against this logic—that church continues to matter because it is the place of habits par excellence. In church, people read the same stories over and over again, say the same words over and over again, sing the same songs over and over again, with many of the same people, week in and week out for years, even decades.

I grew up in church, and the more I think about it—and the more time I devote to it—the more I appreciate it precisely for this relative oddity. I appreciate church for just how hard it is to live in a high-pressure professional setting and to give a clear account of why it is that I “still go.” Maybe because the incongruity—embodied in all those people who are so different from me but who nonetheless get up and go there, too—serves as a standing reminder both of how fragile all the “important” things are and of what might remain when that fragility reveals itself.

The 2014–15 academic year was a rough period for me. I started teaching at Harvard Divinity School, which on its own represents something of a “life event” for a first-generation college student fresh out of graduate school. Yet, that was only the beginning. Three weeks after the fall semester began—right when I’d started to feel something approximating “normal” in front of the classroom—my beloved father passed away. A month after that, my husband and I were unexpectedly evicted from our apartment. And a month after that, my mom was diagnosed with breast cancer. I spent the spring semester suffering from adrenal fatigue, and I didn’t begin to recover until well into the summer.

One might have expected that my church attendance would have taken a dive during this time; I might have expected as much. After all, I’m not required to go. I don’t get paid, and it does nothing to advance my career. It’s not particularly recreational, nor is it relaxing in any ordinary sense. I very well might have been tempted to skip out on church during those troubled months, except for one fact: that August, right before the fateful 2014–15 academic year began, the longtime pianist at my church moved away and left a vacancy.

The church I attend is not a wealthy one, so it is difficult to find a skilled musician who is willing to work dependably for what we can pay. I grew up playing the piano in church. It’s a routine I know well; I know all the songs inside and out, and it’s a skill that comes easily to me. It’s something I enjoy. Thanks to my day job at Harvard, I don’t need extra cash. Still, the most stressful year of my life seems like a strange time to take on a pro bono side gig as a church musician. And, honestly, if the position had opened up even one month later, I might never have agreed to start.

In many ways, though, it was precisely that additional “job” that saved my sanity during such a hard year. There were so many weeks that it would have been tempting just to sleep in or to spend those hours on Sunday with Netflix, in order to simply rest. But I couldn’t, because I had to be there. There had to be music. And, in subtle ways that I didn’t appreciate at the time, being in that space meant being surrounded by loved ones, by people who shared certain habits but whose lives and struggles were also drastically different from my own. Being in that simple sanctuary every week, under the arched ceiling, before the cross, surrounded by the hum of friendly chaos, furnished me with a broader and more robust sense of self by de-centering my own central importance. When I played that music, my body became a conduit through which the bonds between all of the people gathered there—old and young, poor and less poor, every shade of tan and brown—grew stronger as we sang together. While I wasn’t fully aware of it at the time, the experience of sharing music with others turned out to be what I needed most during a time when everything else felt uncertain and shaky.

I still play the music every Sunday, and I’ve come to reflect on the fact that music itself is all about habituation. Playing and singing draw on muscle memory and repetition, all the more so when performed in groups. The songs themselves—perhaps especially for church music—are formulaic. From “Leaning on the Everlasting Arms” to “Come Thou Fount,” the oldest and best hymns are mostly composed of the same simple harmonic structures as many children’s songs and much classic folk and blues music, using the one, four, and five chords, with the occasional major two or minor six thrown in. The predictably of the chords creates a structure for individuated prayers, veiled in common words, to touch one another as they move toward their end. At its best, church music is not particularly original or innovative. But that’s what makes it so powerful. It’s beautiful to play and to sing, not least because it animates the habit of a body writ large, one shaped by rhythm, tone, and words.

There are two times in life when one is likely to reflect on a habit, on the bodily patterns that, for good or ill, have largely been taken for granted: the hard times, like last year for me; and the end of life. As it turns out, I was not the only one whose life was disposed by suffering, music, and habit during that year.

Recently, our congregation said farewell to a member named Gail, who lived to the ripe old age of eighty-seven in spite of admitting to a nearly eighty-year-long smoking habit. To an ordinary observer, Gail was unremarkable, a small, frail fellow with sunken eyes who lived in one of the nearby housing projects. He didn’t usually say much beyond “hello” and “how are you,” but I know from experience that Gail could always be trusted to provide a cigarette lighter in a pinch when the church acolytes’ matches went missing. Many eulogies would paint a bigger picture of Gail. He was, in fact, a man of deep and remarkable talents amid curmudgeonly flaws: a prolific painter and poet, a beautiful soul who could nevertheless be stubborn and selfish and hold an impressive grudge. But one thing was about as dependable as the sun coming up: Gail occupied the same seat in the same pew, near the back on the right side, every single week, almost without fail.

During his final weeks, in hospice for cancer, this loner and lifelong bachelor enjoyed a steady stream of visitors, the majority of whom knew Gail solely from church. Some went because, at one point or another, they had formed a deeper bond with Gail and knew well the tales of his younger life at sea or had shared his devotion to watching (quite literally all of the) Red Sox games. Others went out of the simple habit of Christian duty that compels one to visit the sick and dying.

One of these visitors was a middle-aged, truck-driving Southie native named Mark. After his visit, Mark reported that Gail had insisted on one puzzling request: that Mark sing “Jesus Loves Me.” Now, Mark doesn’t sing in the choir, and he’s certainly never sung a solo in church or anywhere else. And later, as word got around, it seemed that Gail hadn’t asked anyone else to sing—though he’d had some pretty good singers visit him already. Mark told us that before acquiescing to Gail’s request, he said something to the effect of: “Are you sure? If the cancer doesn’t take you, then my singing very well might.” But he knew the song, so sing it he did.

Later, when Mark recounted this to other church folks, remarking how it really was the strangest thing, a woman named Susan pieced it all together. Well, she said, you know Gail sits in the same place every week, and Mark does too—right behind Gail.

Whatever church had meant for Gail, it must have been wrapped up with the experience of hearing Mark’s flawed, beautiful voice behind him every week, singing out the old songs, slightly above the pitch of everyone else’s voice. And that was apparently something that Gail wanted to relive, one more time, at the end of his life.

Living in the world as it is, no one has to go looking for pressures. They will find us. Demands and aspirations compete not only for our time, but also for our claims to identity; they ask us to be authentic, unique, innovative. As I navigate the opportunities, expectations, and challenges that confront me in my daily life, somehow church—with all of its flaws—stands out like Mark’s voice, making me conscious that it’s all the things in between, all the habits taken for granted, that most fundamentally shape who we are. What I needed most in my hardest year was, paradoxically, to be needed. In retrospect, I realized how much making music alongside saints like Gail and Mark sustained us all.

Michelle C. Sanchez is Assistant Professor of Theology at Harvard Divinity School. This article is adapted from a reflection she delivered at the Memorial Church’s morning prayers in October 2015.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.