Featured

Let My People Go

The Scandal of Mass Incarceration in the Land of the Free

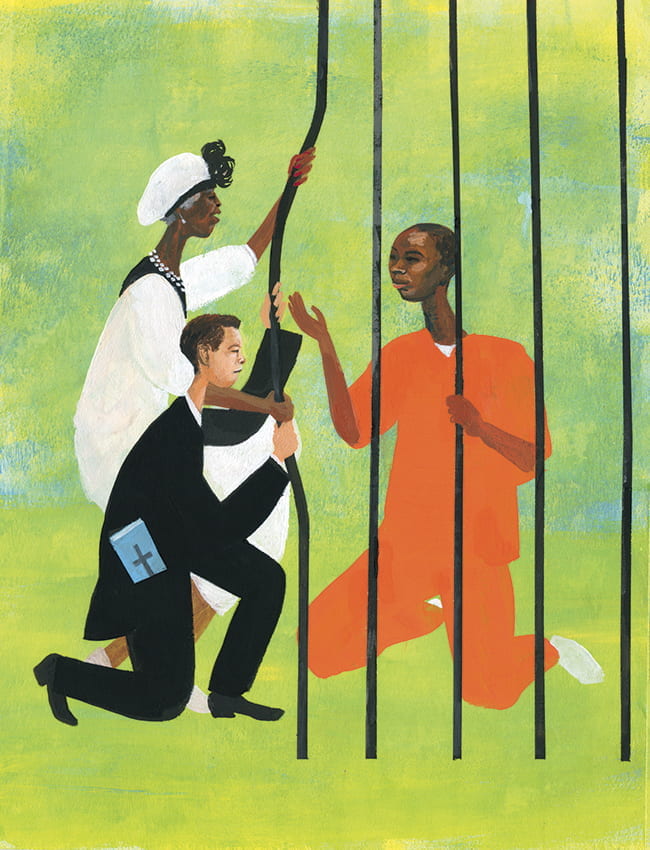

Illustration by R. Gregory Christie

By Raphael G. Warnock

Then the Lord said to Moses, “Go to Pharaoh and say to him, “Thus says the Lord: Let my people go, so that they may worship me.”

—Exodus 8:1

In the spring of 1968, Martin Luther King, Jr. took his last stand for freedom. In a very real sense, he was summoned to Memphis by the sacrifice of two sanitation workers, Echol Cole and Robert Walker, who were crushed to death in the back of a trash truck where they sought shelter from a storm. They were there because black sanitation workers were prohibited from riding in the truck with white workers. Viewed as disposable refuse, they could only ride on the back of the truck or in the compactor area. So, the black bodies of Echol Cole and Robert Walker were literally crushed by the vicious machinery of Jim Crow segregation. We should observe that this was four years after the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and three years after the Voting Rights Law of 1965, the key legislative victories of the movement.

Yet, tragically, it was these crushed black bodies, the latest blow in a long pattern of neglect and abuse, that finally gave fuel to the fledgling Memphis Movement, triggering the radical spirit and action of the local black churches, and producing those historic and iconic signs “I Am A Man.” It is a sign of the oppressed that they must organize movements and carry out campaigns to affirm about themselves what ought to be obvious and to secure for themselves what ought to be automatic. Said these sanitation workers whose hard yet noble labor secured human dignity for all, “I Am A Man.” Negotiating the interstices of racial and gender oppression in the nineteenth century, Sojourner Truth asked, “Ain’t I a woman?” Similarly, activists resisting police brutality and the deadly encounters between law enforcement officers and unarmed citizens as consequences of mass incarceration declare, “Black Lives Matter.”

Those who retort, “No, All Lives Matter” manifestly miss the point. It is oppression itself that makes necessary movements to affirm what ought to be obvious and, likewise, it is privilege itself that renders one blind to what ought to be obvious. One of the biggest obstacles to genuine human community is a glib, unreflective, and uncritical universalism. Justice demands the recognition that all lives are not imperiled in the same ways.

Where are the places that poor bodies and black bodies are being crushed by the machinery of the state or the society at large, demanding the attention of the church and the larger faith community?

That is why a weary but committed Martin Luther King, Jr. made his way to Memphis. He was there to stand with those who needed a movement, carrying signs bearing an inscription that was at once simple, sublime, and scandalous. “I Am A Man.” A little over two months later, he would be slain by an assassin’s bullet on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel. His last book, published a year earlier, was titled, Where Do We Go From Here?: Chaos or Community. I ask: Where indeed? More than a half-century after the poor people’s campaign, where are the places that poor bodies and black bodies are being crushed by the machinery of the state or the society at large, demanding the attention of the church and the larger faith community? While recognizing the structural complexity of racism and its inextricable link to and participation with other constituent parts of hegemonic power, including sexism, classism, and militarism, I would argue that today mass incarceration is Jim Crow’s most obvious descendant and, like its ancestor, its dismantling would represent both massive social and infrastructural transformation and immeasurable transvaluative power in a society still steeped in the ideology of white supremacy. The ideology of white supremacy has created the massive infrastructure of the American carceral state. This massive and increasingly privatized infrastructure has in turn constructed its own distinct ideology.

And, it is this ideology—the distorted, fear-based logic of the carceral state and its construal of blackness as dangerousness and guilt—that imperils black bodies during routine traffic stops (Sandra Bland, Philando Castille); while running in the rain through one’s own gated community (17-year-old Trayvon Martin); while playing in a public park (12-year-old Tamir Rice); and while eating ice cream or playing with family members in the sanctuary of one’s own home (Botham Jean, Atatiana Jefferson). Yet the deadly encounters between police and black citizens so often in the headlines are as predictable as they are tragic. After all, they are but one manifestation of the massive infrastructure and insatiable appetite of a racialized carceral state. I submit that, at root, this is a spiritual problem, symptomatic of a sickness in the body politic. Dr. King understood this. That is why when he, Joseph Lowery, and others formed the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), the organizational arm of his prophetic witness in 1957, their motto was not merely “To End Segregation in America” or “To Secure Voting Rights” but “To Redeem the Soul of America.” That was their motto, focus, and theme. Yet again, it is the soul of America that is in trouble.

The United States of America—the land of the free—is, by far, the mass incarceration capital of the world. Think about that. The land of the free, the shining city on the hill, shackles more people than any other land in the world. Nobody even comes close in the rates of incarceration or even in the sheer numbers of people incarcerated. It is a scandal and a scar on the soul of America. That we are a nation that comprises 5 percent of the world’s population and warehouses nearly 25 percent of the world’s prison population is a scandal and a scar on the soul of America. That we lock up people awaiting trial and keep them there for weeks and months and years (remember Kalief Browder), not because they pose a threat to society but because they cannot afford to pay a bail bond, is a scandal and a scar on the soul of America. That we criminalize poverty and penalize people for being poor is a scandal and a scar on the soul of America. That we have a greater percentage of our black population in jails and prisons than did South Africa at the height of Apartheid is a scandal and a scar on the soul of America. That in all of our large American cities, as many as half of the young black men are caught up somewhere in the matrix and social control of the criminal justice system and that black men have been banished from our families, devastating generations of our families, is a scandal and a scar on the soul of America. These men and, increasingly, women then come out, carrying the mark and stigma of “convicted felon” or “ex-felon” and are therefore confronted with all of the legalized barriers against which Martin Luther King, Jr. and those who battled the old Jim Crow fought, including discrimination in housing, employment, voting, some professional licenses, public benefits, and student loans. It is a scandal and a scar on the soul of America.

Most of the black men in America’s jails and prisons today are charged with nonviolent drug-related offenses. They are casualties in America’s war on drugs. At least, it was a war when the drug was crack and the bodies were black and brown in places like Detroit, Baltimore, the Southside of Chicago, South Central LA, certain communities in Atlanta. We had a WAR on drugs. But now that we are talking about opioids and meth and the public faces of this human tragedy are white and suburban, suddenly we have a public health emergency, an opioid crisis.1 Two very different responses to the same problem!

Public health emergencies are addressed through doctors, public health officials, social workers, therapists, and clinics. Wars are prosecuted against enemy combatants who are either killed or become prisoners of war. In places as large as New York, entire communities may well experience daily the trauma of being subjected to “stop and frisk,” the tools of a de facto occupation in a democratic republic that makes claims to certain constitutional guarantees like presumed innocence, due process, and the like. In places as small as Ferguson, citizen protests are met by military tanks and weapons of war on civilian streets. The truth is that there are a whole lot of people across racial, religious, class, cultural, and generational lines who are self-medicating in the midst of an American crisis—the deep, aching, spiritual void of a culture awash in the broken promises of an individualistic, consumerist impulse of acquisition that even reduces relationships to transactions and short-circuits the difficult but fulfilling work of real intimacy and the joy of genuine community. The data clearly show that black people and white people use and sell drugs at remarkably similar rates. Yet, black people are 12 percent of the general population and over 50 percent of the prison population.

That is why my sister Michelle Alexander has persuasively argued that the mass incarceration of tens of thousands of black men for nonviolent drug-related offenses and the lifelong consequences that result are constituent parts of “The New Jim Crow.”2 Legally barred from the doors of entry to citizenship, symbolized in the right to vote, and denied access to ladders of opportunity and social upward mobility, she observes that those who have served their time in America’s prisons or who plead guilty in exchange for little or no actual prison time are not part of a class but a permanent caste system. I agree. In theological terms, they are condemned to what I call eternal social damnation. Even in the face of heroic efforts to carve for themselves a path of redemption, ours is an exceedingly punitive system that routinely produces political pariahs and economic lepers, condemned, in a very real sense, to check a box on applications for employment and other applications reminiscent of the ancient biblical stigma, “unclean.”3

There is no clearer example of America’s unfinished business with the project of racial justice than the twenty-first-century caste system engendered by its prison industrial complex. Moreover, I submit that there is no more significant scandal belying the moral credibility and witness of the American churches than their conspicuous silence as this human catastrophe has unfolded now for more than three decades. To be sure, scores of American churches have prison ministries and some even have reclamation ministries for formerly incarcerated individuals.4 But there is a vast difference between offering pastoral care and spiritual guidance to the incarcerated and formerly incarcerated, and challenging, in an organized way, the public policies, laws, and policing practices that lead to the disproportionate incarceration of people of color in the first place. This is one of most pressing moral issues of our time. We need a national, multifaith, multiracial movement to end the scourge of mass incarceration, the insatiable beast whose massive tentacles place black children in chokeholds and brown babies in cages on both sides of the border.

But how do you build an effective social movement, particularly among churchpersons, when the primary subjects of its advocacy are those stigmatized by the pejorative label “illegals,” in the case of our Latinx sisters and brothers subjected to draconian tactics of immigration enforcement, whether they are citizens or not. How do you win public sympathy and support for “convicted felons”? It is one thing to stand up for Rosa Parks, whom Martin Luther King, Jr. called “one of the most respected people in the Negro community.”5 It is quite another to fight for the basic human dignity of persons whose entire humanity has been supplanted by a legal and moral stigma. In many instances, they may well bear real culpability for their condition.

Indeed, this is part of the conundrum posed by racial bias in the criminal justice system. In a world where ordinary black people must still navigate every day the racial politics of respectability, bearing the burden of being, in the words of that old folk saying, “a credit to the race,” those who find themselves caught up in the criminal justice system have not kept their side of the deal. If many outside of the African American community view these young black men who track through the courtrooms of every major American city every single day with fear and contempt, many within their own families and churches harbor feelings of disappointment, anger, and ambivalence. They are the ultimate outsiders, stigmatized for life as both “black” and “criminal,” two words that have long been interchangeable in the Western moral imagination.

Four hundred years after the arrival of more than 20 enslaved Africans in Jamestown, Virginia, the black body remains the central text in the narrative of a complicated story called America. For all who would understand who we Americans are and how we have arrived, the black body is essential reading. There is no American wealth without reference to black people. Yet, the black body is viewed essentially as a problem, sitting at the center of what Gunnar Myrdal characterized in 1944 as “An American Dilemma.” Four hundred years later, formerly enslaved black bodies and branded black bodies and lynched black bodies and raped black bodies and segregated black bodies are now stopped, frisked, groped, searched, handcuffed, incarcerated, paroled, probated, released, but never emancipated black bodies.

Like many, I have witnessed the human cost of this story and stigma, and I have felt its pain personally, experiencing it in my own family. I am the youngest of seven boys. My brother Keith, who is just above me, is serving time right now in a federal prison. He was sentenced to life, his natural life, in 1997, as a first-time offender in a drug-related offense in which no one was killed and no one was physically hurt. In fact, because the entire crime scenario was created, concocted, and controlled by the federal authorities, no one got high. In this operation, no actual drugs ever hit the streets and none were removed from the streets. My brother was sentenced to life. He is a veteran of the first Gulf War and has appointed himself as a model prisoner since his incarceration 22 years ago. It is the stigma of color and criminality that makes his story not as uncommon as one might think.

But no group is more stigmatized than those persons on death row. After years of steady decline and presumptive death by many criminologists, the death penalty reemerged, as part of a conservative backlash, in the years immediately following the civil rights movement. In a real sense, it is the final failsafe of white supremacy, for the data clearly show that its use ensures that, in the final analysis, the lives of white people are to be regarded as more valuable than the lives of black people. That is why the race of the victim, more than anything else, determines the likelihood that the punishment will be death by execution.6 And if the victim is white and the presumed perpetrator is African American, the symbolic power of condemning that cardinal trespass is every bit as important as ensuring that the actual African American who committed the offense is executed. That this is still true decades after the era of lynching became exceedingly clear to me a few years ago during my public advocacy for death row inmate Troy Davis.

By the time I met Troy Davis and became involved with his case, both as pastor to him and his family and as a public advocate for the sparing of his life, he had been on death row for nearly 20 years, convicted in 1991 for the 1989 slaying of Savannah, Georgia, police officer Mark Allan McPhail. It was 2008, and we held the first of several rallies for him at Atlanta’s historic Ebenezer Baptist Church, where I serve as senior pastor.7

Davis’s case had already gained national and international attention and brought together unlikely allies in the struggle to save his life. It embodied so clearly all that is wrong with America’s deployment of the death penalty that even death penalty proponents like William Sessions, former head of the FBI, and Bob Barr, a conservative Georgia congressman, stood in agreement with liberals like President Jimmy Carter and Congressman John Lewis against the execution of Troy Davis. The trial provided no physical evidence in support of Davis’s conviction. No murder weapon, DNA evidence, or surveillance tapes were ever produced, and, in a trial based largely on witness testimony, seven of the nine witnesses supporting the prosecution’s case recanted or materially changed their testimony.

There was so much doubt surrounding this case that on three separate occasions, Davis’s execution was stayed within minutes of his death. One fall afternoon, I sat, in a pastoral visit, at his cell, as he reflected on his life, its meaning, and his hope that somehow his story might be a bridge to a better future and a larger good. We talked. We prayed. We sat silently. We said goodbye.

Two days later, I stood in a prison yard with his family and hundreds of others one fall night, September 21, 2011, as Troy Davis was stretched out and strapped to a gurney, bearing an eerie resemblance to a crucifix, and executed in my name, as a citizen of the State of Georgia, by lethal injection.

In the years that I have continued to fight for Davis and others like him, for the soul of a nation scarred by the scandal of mass incarceration and for the lives of young black men like Trayvon Martin, who was tragically endangered and murdered by the stigma of blackness as criminality, I have often reminded myself that I preach each week in memory of a death row inmate convicted on trumped-up charges at the behest of religious authorities and executed by the state without the benefit of due process. The cross, the Roman Empire’s method of execution reserved for subversives, is a symbol of stigma and shame. Yet, the early followers of Jesus embraced the scandal of the cross, calling it the power of God. To tell that story is to tell the story of stigmatized human beings. To embrace the cross is to bear witness to the truth and power of God subverting human assumptions about truth and power, pointing beyond the tragic limits of a given moment toward the promise of the resurrection. It is to see what an imprisoned exile of a persecuted community saw as he captured in scripture the vision and hope of “a new heaven and a new earth.”

That is why Ebenezer Baptist Church, spiritual home of Martin Luther King, Jr., has been trying to find a way to faithfully and effectively bear witness to God’s justice. This past summer, we organized a national, multiracial, multifaith conference focused on the collective work of dismantling mass incarceration by catalyzing the resources of people of faith and moral courage in a movement that operates at the local, state, and national levels. Our co-conveners were Auburn Theological Seminary in New York and The Temple, the oldest Jewish congregation in Atlanta. We are now at work for the long haul and we have four objectives:

1) To train and equip pastors, rabbis, imams, and other faith leaders and their teams with practical tools for addressing their ministries to mass incarceration as a social justice issue in their local setting;

2) To identify and coalesce around a strategic legislative agenda at the local, state and national levels;

3) To organize an interfaith network of partners focused on abolishing mass incarceration; and

4) To lay the groundwork for the development of a new media strategy for reframing the public understanding of the prison industrial complex and its implications for public safety, quality of life, etc.

This national effort, taken on in partnership with others, actually builds upon years of advocacy and activism. Seeking to leverage our legacy for good work in the present rather than rest on the historic laurels of a glorious past, we have been busy addressing our ministry, particularly over the last several years, to a criminal justice system that crushes the poor in the incinerator of a biased system whose outcomes are too often more criminal than just. From time to time, we have gotten engaged as public advocates in certain cases; we have raised offerings and have partnered with celebrities like Rapper TI and actor Mark Ruffalo to bail poor people awaiting trial out of jail and; we raised our voices as part of a coalition of conscience that successfully convinced the mayor and the city council to end cash bail in the City of Atlanta. Moreover, current Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms has committed to closing the city jail and turning it into a youth center that invests in our future.

But much of our work has been focused on expungements (record restrictions). In 2016, we came together with other Fulton County officials to organize and host our very first expungement clinic, a one-stop shop in the church’s banquet hall that cleared the arrest records of hundreds of citizens who had been arrested but never convicted. Like millions of Americans who have arrest records, they were either barred from or limited in their employment options, rejected in their applications for housing, apartments, and other features of a prosperous and dignified life. These expungement events have been emancipation moments for people looking for a second chance.

None of us wants to be forever judged by our worst moment, and each of us has some record that cries out for grace and redemption.

I remember the very first one and the joy I felt, as I walked into our sanctuary that Saturday morning and realized that almost everyone gathered that day had a record. But then I thought to myself that in a real sense, that’s true every Sunday. None of us wants to be forever judged by our worst moment, and each of us has some record that cries out for grace and redemption. Some time after the first event, I was sitting in the chair at the barbershop. My barber was finishing my haircut and I was rushing to get out of the chair to my next appointment when another patron walked up to me. He said, “Rev, that was a great event y’all had.” I said, “What event?” He said, “The expungement event.” I politely said, “Thank you,” as I was trying to get to my next appointment. He said, “Rev! Wait. You don’t understand. You cleared my record. A bad check charge from 20 years ago.” I froze. He appeared to be in his late 50s, well dressed, and he looked so “respectable.” He continued, “As a result, I’ve got a better job, my income has gone up and my life is better.” I congratulated him, shook his hand, and was headed for the door when he said, “Rev, wait. A young couple in my family had a baby that they did not have the means to raise. The baby was headed to foster care. But because I came to the church and somebody cleared my record, I was able to adopt my great niece.” The trajectory of two generations changed in one day.

I am glad. But I am also sad, because he had never actually been convicted of anything! He had an arrest record. He was free. Yet, for 20 years, he had been bound by the massive tentacles of our prison industrial complex. While helping people like him, it is that fundamental problem that we seek to address in a nation where nearly 30 percent of adults have a record. And now, with a faith kit and a wonderful documentary film put together by our partners at Public Square Media, we are teaching other congregations to do the same. People of faith and moral courage should lead the charge and embrace the challenge of saying to a failed system, “Let my people go.”

That is what God told Moses to tell Pharaoh. “Let my people go that they may worship me.” Liberate them from human bondage so that they might blossom and live lives of human flourishing, lives that give glory to God rather than to human systems. Moses had a speech impediment, yet God picked him. Moses had a record. Yet, God picked him in spite of his record. Or, maybe God picked him because he had a record. In my tradition, God has a record of using people with a record:

Moses had a record. He slew an Egyptian. He killed a man. God had more in store for him.

Joseph had a record. Long before a Central Park case and a ruthless prosecutor, there was Potiphar’s wife. Joseph was thrown in prison, but he held on to his dreams.

The Three Hebrew Boys had a record. And they were sentenced to death for an act of civil disobedience.

Daniel was charged, convicted, and thrown into the lion’s den.

John was imprisoned on an island called Patmos, the Rikers Island of that day. There, he saw a new heaven and a new earth.

Jesus had a record—not surprising, given his start. Born in a barrio called Bethlehem. Smuggled as an undocumented immigrant into Egypt. Raised in a ghetto called Nazareth. But he came, saying, “The Spirit of the Lord is upon me . . .”

They brought him up on trumped on charges. Convicted him without the benefit of due process.

Marched him up Golgotha’s hill. Executed him on a Roman cross. Buried him in a borrowed tomb.

But he was so powerful that he turned the scandal of the cross into an enduring symbol of victory over evil and injustice, and his movement was so contagious that he got off the cross and got in our hearts.

He is my redeemer and liberator, and in his name and in the name of all that is good and just and righteous and true, we must stand together, fight together, walk together, organize together, vote together, pray together, stay together, and say together, “Let my people go!”8

Notes:

- Yet the changing face of this this public health crisis hasn’t meant that African Americans are receiving equal treatment or care. An NPR report in 2019 was titled, “Addiction Drug Going Mostly to Whites, Even as Black Death Rate Rises.”

- This is the title of Alexander’s landmark book published 10 years ago: The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness (The New Press, 2010). A new tenth anniversary edition came out in 2020. Listen to or read an interview with Alexander on The New Yorker Radio Hour.

- See David P. Wright’s discussion of “Unclean and Clean” in the Old Testament and Hans Hubner’s discussion of the same topic in the New Testament in The Anchor Bible Dictionary, vol. 6,ed. David Noel Freedman (Doubleday, 1992), 729–45. Among the many examples of Jesus’s radical confrontation with the religion and politics of uncleanness are Mark 2:15–17 and Luke 15:1–2.

- See Reclamation of Black Prisoners: A Challenge to the African American Church, A Book for Individual and Congregational Study, ed. Glorya Askew and Gayraud Wilmore (ITC Press, 1992).

- Martin Luther King, Jr., Stride toward Freedom: The Montgomery Story (Harper & Row, 1958), 44.

- See chap. 18 in Dale S. Recinella, The Biblical Truth about America’s Death Penalty (Northeastern University Press, 2004).

- Jen Marlowe and Martina Davis-Correia with Troy Anthony Davis, I Am Troy Davis (Haymarket Books, 2013).

- This lecture was delivered on October 16, 2019, as part of the William Belden Noble Lecture series at Harvard University’s Memorial Church. Warnock’s subsequent lectures in the series were scheduled for the spring of 2020 but were canceled because of COVID-19.

Raphael G. Warnock has been the senior pastor of the historic Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta since 2005. He is a Morehouse College graduate, received his master of divinity and doctor of philosophy degrees from Union Theological Seminary, and is the author of The Divided Mind of the Black Church: Theology, Piety, and Public Witness (NYU Press, 2013). He won the 2020 Senate special election in Georgia and will begin serving shortly after the results are certified.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.

I pray this goes for all races that are held in the corrupt prison system in Georgia.

Especially moving and effective, I think, after Rev. Warnock gets to the personal stories. I’ll see what I can do to share the speech. Thanks.

Those with ears ought to listen and those with empathy ought to come forward and those in pastoral platforms should follow suite and boldly speak and teach the truth. That is the only way of shaming the evil white supremacy life in America. Western Christianity seems to forget the critical demand and proclamation when God gave Moses the profound message to Pharaoh. “Let my people go” so that they can worship me as free people not in chains.

Soooo well written….thank you, Pastor Warnick!….dee mcquesten

I serve on a statewide public defender board. How can indigent defenders better drive transformation.? Are there talking points to better educate policymakers and the public? Any tools for change are appreciated.

Peace

Jim Brennan