Perspective

Blessed Are the Caregivers

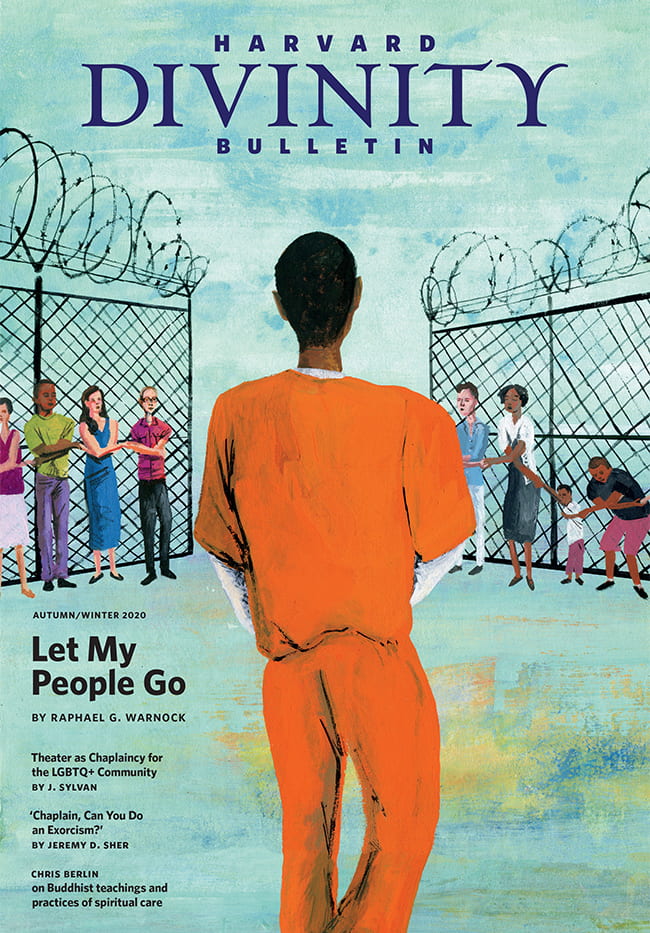

Cover illustration by R. Gregory Christie. Cover design by Point Five Design.

By Wendy McDowell

care (v.)

Old English carian, cearian “be anxious or solicitous; grieve; feel concern or interest,” from Proto-Germanic *karo- “lament,” hence “grief, care” (source also of Old Saxon karon “to lament, to care, to sorrow, complain,” Old High German charon “complain, lament,” Gothic karon “be anxious”), said to be from PIE root *gar- “cry out, call, scream.”

—Online Etymology Dictionary

A few months after I finished a five-month stint as a student teacher in 2007, a senior boy I’d taught was killed in a car accident. Paul was funny and sweet and gangly. He was known in his high school for being a graceful basketball player, but I knew, having been an assistant teacher in his creative writing class, that he was also a talented writer and he was hoping to study English or journalism in college. The driver of the car, Paul’s friend, had been drinking the night of the accident and was speeding on a hilly road when he crashed into a house. The friend survived.

I felt compelled to attend the calling hours and funeral, but I was struggling with how I could best be of support to others. Should I be a “pillar of strength” so my former students could lean on me? And what words of comfort could I possibly offer to Paul’s friends, and to his grieving family? The death of a child renders the usual platitudes hollow and useless.

While pondering all of this, I happened to run into Sarah Coakley at work.1 I knew that Sarah had served as a chaplain in hospital and prison settings and as a parish priest. I trusted she might be able to help me. I explained the situation, and she provided me wise counsel. I remember this piece of advice most clearly: “Don’t be afraid to let your students see you grieve,” she said. “They need to know you are with them in their sorrow.” Her perspective changed the way I thought about “caring” in this moment of crisis for a family and a school.2

What does it mean to care in the midst of a tragedy? What does caring look like when the tragedy is widespread and ongoing? As I write this, Americans are engaged in a contentious election many are calling a battle for the soul of our country, and we are facing twin pandemics of COVID-19 and racism. The virus has upended all of our lives—but not equally. It is disproportionately killing the most vulnerable in our society,3 and women of color throughout the world are bearing the biggest brunt from its devastating economic consequences. Many mental health professionals are predicting, and already starting to see, a “tsunami of grief” from the death toll, job losses, family disruptions, and social isolation.

In this same period, the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and other black citizens have sparked another reckoning with 244 years of crushing white supremacy in this country. As Raphael G. Warnock details clearly, this ideology “has created the massive infrastructure of the American carceral state,” an apparatus of oppression that results in regular, deadly encounters between African Americans and the police, and that has made the United States “the mass incarceration capital of the world.” Warnock points out that this has forced activists to organize again and again throughout US history to declare “what ought to be obvious [and] automatic”—the worth and dignity of each human being.

How do we care for one another in a nation that has a “sickness in the body politic” (Warnock’s words, again), and when that nation—literally and metaphorically—is on fire?

The etymological root of the word “care” points us to a full range of responses. Based in grief, lament, and sorrow, its actions include “to cry out, call, scream,” and “to complain.” The authors in this issue are chaplains, faith leaders, and professors. In these roles, they lament inequities, cry out for change, and “feel concern and interest” for their students, parishioners, and patients, helping those they serve to expand their horizons and accompanying them through the grieving process.

In lament, Warnock calls on faith communities to focus “on the collective work of dismantling mass incarceration by catalyzing the resources of people of faith and moral courage…at the local, state, and national levels.”4 Elam D. Jones asks us all to make “serious, sustained commitments to contribute to the protection and provision of social allowances and care that might minimize [the] physical, psychological, and economic sacrifices” of essential workers. Hospital chaplain Erica Rose Long translates this into public policy, saying, “When I think about the exhaustion, the distress, the anger, and the grief that clinical staffs are facing right now, the one thing that’s really going to make that change is health-care reform.”

Mara Willard’s reading of The Testaments cries out for self-reflective, forward-looking feminisms. “Atwood is raising questions of female complicity with patriarchal power,” Willard writes, and “questions about second-wave feminism’s intersection with class and race, under conditions of late neoliberalism, are the ones that need asking.”

Other authors demonstrate how to “treat the people’s needs as holy.”5 Jeremy Sher shares his intricate work doing spiritual assessments with psychiatric patients suffering from auditory hallucinations (“hearing voices”). Chris Berlin describes how “discerning wisdom plus competency is the foundation for skillful responding” as a Buddhist chaplain. Emily Click encourages us all to recognize the “false binaries” we may hold and to be open to new modalities of solidarity as we bear witness to universal suffering.

Mark Jordan, J. Sylvan, and Cody Hooks offer different prisms on how and where queer communities provide spiritual formation, care, and comfort. They point to the importance of “community practices of historical discernment,” as Jordan puts it, and to the need for collaborative artworks that uplift and sustain us.

It also seems like the right time for Giovanni B. Bazzana’s new book on spirit possession and exorcism among early Christ groups, which aims to take seriously the lived experience of many Christians—including Catholics, Pentecostals, and other groups, and to be “intelligible to individuals who are not a part of historical-critical academic discourse.”6 By challenging the limitations of past scholarship that has mostly avoided the miraculous and supernatural, he models how to be inclusive of traditions and experiences that have too often been marginalized.

When Jesus declared “Blessed are those who mourn,” I don’t think he meant that mourning is a desirable state but he wanted to reassure his listeners that mourning is a divinely protected state—it is a sacred, liminal time during which God is in our corner offering comfort and peace. Other blessed conditions in Matthew 5 include when we “hunger and thirst for righteousness,” are “merciful,” “pure of heart,” or “poor in spirit,” and act as a “peacemaker.”7

The Beatitudes is a capacious list, but if you can’t find yourself anywhere in it, you are not among the blessed, which ought to be a signal to change your way of living in the world (lo and behold, the list doesn’t include “Blessed are the power-grabbers,” or “Blessed are those who sow division”!).

Whatever traditions and texts you hold dear, I hope this issue inspires you to cultivate an ever-deepening compassion for those who are suffering and to let your grief inform your care and “complaint” for others. As Jones suggests, we are all called to be heroes right now.

Notes:

- Casually running into renowned scholars, theologians, and faith leaders is one of the perks of working at Harvard Divinity School.

- I understood this didn’t mean making a display of grief that would get in the way of supporting those in Paul’s inner circle. Showing heartfelt sorrow is a communal act that affirms our love for the person who has passed away, and enables us to connect to others from a place of vulnerability—a different model of strength than one that encourages “putting a lid” on our grief.

- The rates of both infection and death are higher in black, brown, and indigenous communities, and the virus is especially dangerous for elderly patients in nursing homes. Somewhere I read this quote that has stuck with me: “Inequality is to COVID transmission what the mosquito is to malaria transmission.”

- In his role as senior pastor of the historic Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, Warnock models what care looks like in all of its registers. His church has hosted expungement events to clear the arrest records of people who had been arrested but never convicted, which have been “emancipation moments for people looking for a second chance.”

- Obery M. Hendriks, Jr. coined this expression in his book The Politics of Jesus: Rediscovering the True Revolutionary Nature of Jesus’ Teachings and How They Have Been Corrupted (Doubleday, 2006).

- Bazzana describes how he “defamiliarizes” ancient texts about Jesus and Paul by comparing them “with contemporary ethnographic descriptions and accounts of possession and exorcism.”

- The “poor in spirit” has been used by some interpreters to turn our attention away from material suffering, but for me, it encompasses physical, psychological, spiritual, and social maladies. Like the Buddha, Jesus seemed to be well aware of what we now call the “mind-body connection”!

Wendy McDowell is editor in chief of the Bulletin.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.