FEATURED

Facing Death without Religion

Secular sources like science work well for meaning making.

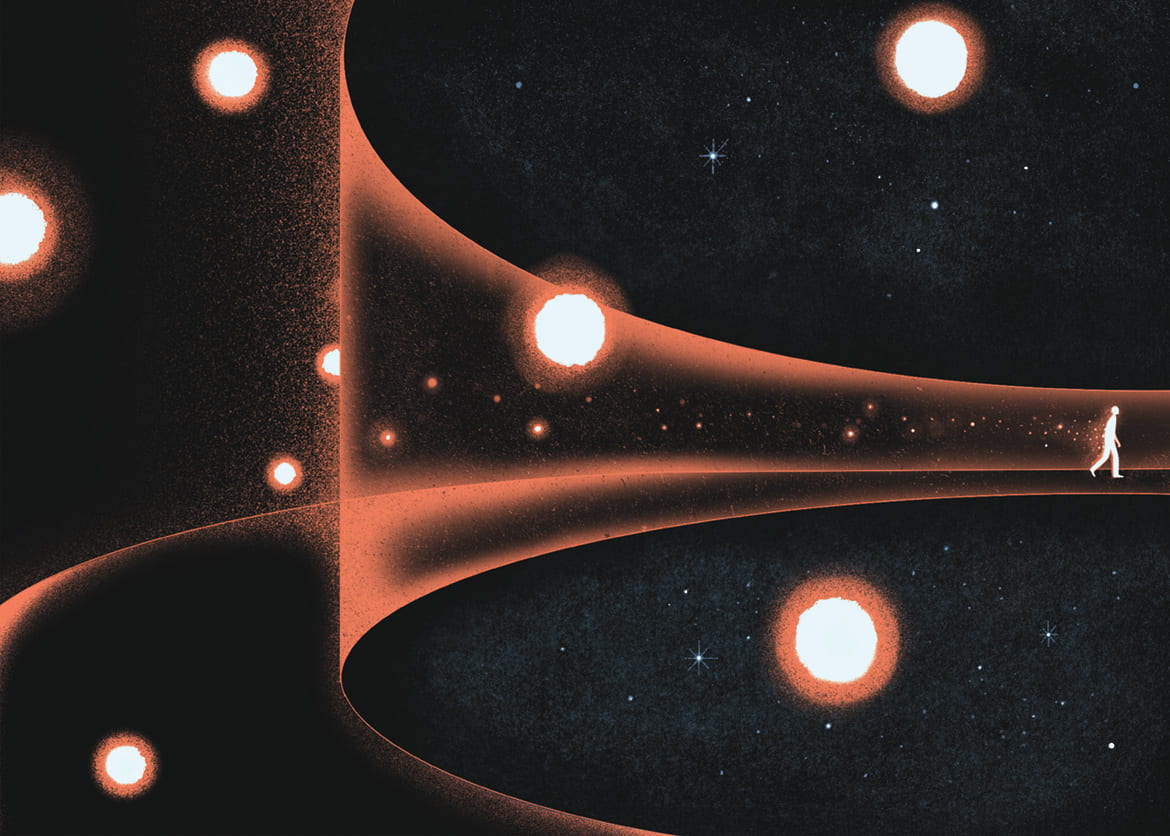

Illustration by Jun Cen c/o Heflinreps Inc.

By Christel Manning

There are no atheists in foxholes, they say. My favorite uncle was, to all who knew him, a decidedly nonreligious man, never setting foot in a church except to bury his mother and refusing the visit of a minister in his last days. Yet the Haitian woman who tended to him as he struggled with his final breaths claims he spoke to God the night he died.

Research psychologists argue that religion was born from the fear of death,1 and it seems like every year there’s a new bestselling book about scientists finding religion in the face of their own mortality.2 So when I tell people that far fewer elderly people than young people are nonreligious, they are usually not surprised. The proportion of religious Nones in the U.S. population has grown dramatically, but much of that growth is driven by the young: only 9 percent of those over 65 are unaffiliated, compared to 35 percent of those under age 30, and we see similar proportions for atheists and agnostics.3 Not only are older cohorts more religious, but some people actually get more religious as they age.4

It would be easy to attribute these patterns to religion’s unique ability to give meaning to our mortality. Many people assume that facing death without religion renders life pointless and unbearable, that only exceptionally strong and stoic individuals can face the void that is death without a religious framework. But that assumption is just that, an assumption, because we don’t have much data to back up such notions. The study of Nones has focused mostly on the young, and studies of the aged have tended to ignore atheists. Secularity is growing even among the old, and yet few have bothered to ask elderly secularists how they face death without religion.

How do atheists, agnostics, and other seculars find meaning at the end of life? How do they make sense of mortality without religion? I have spent the last two years exploring these questions, sifting through hundreds of studies and interviewing individuals in nursing homes, senior centers, and in their homes. This article reports on some of what I have learned.

When I reviewed the literature, it seemed at first that the foxhole theory was right. A substantial body of research suggests that religion helps people cope with dying.5 While some of that positive impact is tied to community (the social support offered by religion), the provision of meaning is a significant causal factor: religion can offer coherence, a feeling of confidence that our life events are ordered or purposeful, rather than random and chaotic, which in turn can confer a sense of control over one’s life.6

The end of life is frightening because it’s a new experience; we don’t know where we are going. If a person is ill, dying may entail physical pain and disability. Even in the best of circumstances, we may find ourselves unable to engage in basic physical activities we used to take for granted, or facing the loss of mental acuity. And for most older people, the final years bring the loss of partners, family members, and friends who would otherwise support them at this time. Religion can provide a framing for why we are in pain or why we had to lose somebody we love—for example, if suffering is viewed as redemptive or part of a divine plan. Religion also answers questions about what happens after death, whether through complex and varied conceptions of reincarnation in Buddhism and Hinduism, or through comforting beliefs that we will see loved ones again in heaven, as in some Christian traditions.

There are increased rates of depression and suicidal behavior among elderly people.7 Religious traditions can provide supportive social networks, and offer people in the final years of life steps to work through devastating losses and to continue living a purposeful life. Reading scripture or meditating is something an individual can do, even with physical disability. And when a loved one dies, rituals like sitting Shiva or preparing for a funeral mass offer structured, familiar activities for loved ones to do.

But saying that religion helps people find meaning in the face of death does not prove that meaning is absent without religion. Recent reviews of such studies show that they focus almost entirely on religious people, usually comparing more devout people to those who are less devout. Only rarely do they study individuals who are committed seculars, i.e., those who have replaced religion with some other source of meaning.8 The few studies that engage in more rigorous comparisons suggest that nonreligious people do just fine. Peter Wilkinson and Peter Coleman found that both atheism and religion can be a source of meaning for older people, and it is the strength of conviction, rather than being religious or nonreligious, that enables effective coping.9 Coleman and Marie Mills suggest that while uncertainty is sometimes linked to depression, questioning also links to growth.10 Bethany Heywood and Jesse Bering have shown that the nonreligious do, in fact, frame life events using purposive narratives.11 But we know very little about the content, patterns, and sources of these narratives.

What we do know is that finding meaning is an interpretative act. Human beings make meaning by telling stories about our lives.12 Language does not just capture and reflect experience but creates it. Even when people are telling stories that are similar in content, they use linguistic, rhetorical, structural devices to create different sets of meaning. There are broader social narratives that shape individual storytelling, what Ann Swidler has called the cultural toolkit.13 These social narratives can come from religion or science, from a particular family background, or from popular culture.

I like to conceptualize meaning making as a kind of mapmaking enterprise. The stories we tell are the way we connect the dots and orient ourselves. It’s like when the ancient Greeks imagined lines between the stars and gave names to the various constellations. Without a constellation map to life, events can feel random, and we can feel lost, frightened, and confused, especially when we are entering new territory. But when we have a map, we have a path to follow; we have agency and power. Religion has long been acknowledged as a powerful mapmaking tool because it creates meaning on two levels: it provides generic narratives that function as a cultural tool for constructing meaning; and these narratives inform, infuse, and frame each believer’s personal narrative. In my current research I am seeking to understand how this works for nonreligious people. Are there generic stories that secular adults use to make meaning, especially at the end of life? If so, how do they rework these stories to create meaning from their personal experience?

If meaning making is about storytelling, then I knew I needed to listen to respondents’ stories. So the study, begun in late 2017 and currently in its final phases, is based on personal interviews with elderly seculars. The two main criteria for inclusion are age (70 and over, though I include younger individuals with terminal illness) and nonreligious identification. Participants were recruited in nursing homes and senior centers, with the assistance of the AARP and various secularist organizations.

To date, a total of 97 interviews have been conducted in various locations across the United States. Although participants were not randomly selected and may or may not be representative of the nonreligious elderly population as a whole, this is a large sample for a qualitative study and reflects important demographic patterns. It is gender balanced and includes 12 black respondents (surveys show that only 4 to 7 percent of African Americans identify as nonreligious).14 It includes respondents from regions where nonreligiosity is more socially accepted (New England) and where that is less the case (so-called Bible Belt states such as Texas and Georgia). Nonreligion comes in many varieties (e.g., atheist, agnostic, humanist, freethinker), and the sample reflects that diversity. Interviews are semi-structured, beginning with questions about the past and then proceeding to more reflective questions about the present and the future, including the respondent’s impending death. These conversations are conducted in private homes and in institutional settings, depending on the preferences of the subjects, and they range in length from 45 minutes to 2.5 hours. All interviews are transcribed for coding and analysis.

The study of so-called Nones poses unique challenges that are readily apparent as I begin to review the data I collected. The first and most obvious is theoretical: we are looking at a population that is defined in terms of what they lack—religion—and yet there is no consensus on what religion is. The models of religion employed in the social sciences are largely based on Christian constructs. It has long troubled me that Pew, Gallup, and other big survey organizations use measures such as belief in God, prayer, attendance at services, and denominational membership or identification with particular traditions, and then apply these cross-culturally to places like China or Japan, despite evidence that this is a poor fit.15 Even within the United States, where Christianity is the dominant religion, about half of Nones are people who identify their religion as “nothing in particular,” a phrase that leaves considerable room for further definition.

I have proposed elsewhere16 that we distinguish American Nones into at least four categories: Unaffiliated Believers have conventional, usually Christian or Jewish worldviews, but reject organized religion; Philosophical Secularists have replaced religion with a distinct nonreligious worldview such as atheism, Humanism, Free Thought; Spiritual Seekers claim no religion because they create their own worldviews from more than one spiritual tradition; and last, those who are indifferent to any kind of religious, spiritual, or secular worldview. This model has apparently been helpful to subsequent researchers,17 and yet my current work on elderly Nones is raising new questions.

Consider Jack, an 86-year-old retired engineer I interviewed at his home in the Northeast.18 He was raised Jewish in a family that fled Nazi Germany, and he continues to attend a conservative synagogue with his wife. But he identifies as atheist, proudly informing me, “I think Judaism is the only religion that does not require belief in God.” Trained in physics and chemistry, he rejects any kind of supernaturalist framework and sees all ritual as theater—and yet he finds value in tradition and creates his own personal meaning from it. Thus, he and his wife regularly host a secular Passover at their house to pass on the family tradition, but Jack interprets the Exodus story as a metaphor for his hope that freedom will eventually triumph over oppression. Perhaps we need another category for people like Jack, such as culturally religious, or existentially secular, or both.

A second challenge in researching the nonreligious is methodological: how do you access them? Religious folk are easily located through the organizations they affiliate with. Not so with the Nones. Even among self-identified atheists, the vast majority do not affiliate with atheist organizations.19 The negative stigma still associated with atheism in the United States compounds the problem,20 especially for African Americans and the elderly for whom religious identification continues to be a strong social norm.

In the interviews I conducted with black respondents, the theme of being a “double minority” was prominent. They were old enough to have personal memories of the civil rights movement, which had close ties to the black church. Turning their back on the church can feel like betrayal, and they are unsure of their place in organized secularism. Take Andre, a 70-year-old physician from Atlanta. Raised Baptist, he left church in his 20s to join the Nation of Islam and then a decade later came to reject religion altogether. He reports that his parents and his sister “got upset when I became a Muslim, but since I came out as atheist they won’t talk to me at all.” Andre has attended the occasional event at a local humanist association but finds he’s consistently “the only black person there.”

White atheists can feel isolated as well. I interviewed Fred, a 79-year-old military veteran, at a nursing home in Massachusetts. A high school dropout, he joined the army and after his release held a series of low-paying jobs in construction and long-distance driving. He fell into drinking and was homeless for more than a year before a social worker found him a place in a Catholic nursing home. Fred told me, “I can’t talk about my beliefs here.” He feels like an outsider because he does not believe in God and thinks religion is a “giant hoax” invented to “make people feel better about death.” But he likes having a roof over his head.

I learned that recruiting respondents for this kind of study means finding ways to make them feel safe. When I posted flyers at that nursing home seeking volunteers for study of nonreligious people, I got zero responses (even though their records show more than a third of residents stated no religious preference). So I collaborated with the staff there to personally invite those individuals they thought might fit my criteria. I also spent weeks walking about and knocking on doors, introducing myself and telling people about my project (which was how I found Fred). This was a rather time-intensive recruitment effort, but it yielded many more interviews. I mentioned earlier that surveys show significantly lower rates of nonreligiousness among blacks and older people. Now I wonder about those numbers.

As I listened to individuals tell their stories, I was struck by their eagerness to tell them. I remember sitting by the bed of a 91-year-old woman who was nearly blind and had both her legs amputated due to diabetes. We had talked for about 45 minutes and had gotten to the part where I planned to inquire about her thoughts on death. She was one of my first interviews, so I hesitated, reminding her that she did not have to answer if she did not want to. She cut me off, saying: “It’s OK to talk about this, honey. I am 91 and not in good shape, so I spend a lot of time thinking about death.”

There is surely some selection bias at work here: respondents to an end-of-life study probably feel comfortable discussing their thoughts on the matter. But it is also true that meaning making is particularly salient as we approach the end of life. Not only is death humanity’s most profound crisis of meaning, but facing our own mortality also triggers an assessment of the life that is behind us: the good experiences and the regret, what our legacy is and whether there is still time to improve it. In other words, meaning making at this stage of life is both backward and forward looking, mapping past and future.

The 97 stories I collected confirm some of the conventional assumptions about nonreligious people. Most do not believe in an afterlife, at least not in the sense that a soul or spirit or some conscious aspect of the self survives the death of our brain. And most do not think the universe, or human life, has an inherent purpose. But, contrary to conventional assumptions, that does not lead to despair or anomie. Instead, I found that secular elders construct their own meaning-making narratives from secular rather than religious sources, and there are distinct patterns of secular meaning making that can be compared to religious ones.

There are certain story types that I encountered again and again, suggesting that these meaning maps are not idiosyncratic but represent a kind of ideal type of narrative nonreligious individuals use. These narratives function similarly to religious narratives by providing coherence (ordering the past) and control (action steps for the future). Like religious narratives, they articulate the meaning of human existence to something bigger than ourselves, and they suggest a moral dimension.

Science-based narratives can evoke a sense of awe and wonder, a perception that we are part of a meaningful universe that gives order to our past and offers insight for the future.

By far the most common narrative framework was rooted in the scientific understanding that we are all part of nature (more than half of the respondents used some variation of it). Previous research suggests that scientists are more likely than the general population to be nonreligious,21 so it was not unexpected that many of my respondents were trained in the sciences, as engineers, chemists, and physicians. More surprising was how science functioned as a meaning-making narrative. We often think of science as cold and hard and value neutral. Max Weber famously wrote of how the ascendancy of science over religion in the modern world has led to “disenchantment.” Yet I found that science-based narratives can evoke a sense of awe and wonder, a perception that we are part of a meaningful universe that gives order to our past and offers insight for the future.

Although there were many variations, the basic arc of this narrative is that humans are part of nature; we have a place in evolution and a role in the ecosystem, and our role continues to develop and change. What happens to us has material causes that can be explained by science. And though there is no inherent purpose in the universe, we can create meaning for ourselves. Life is reciprocal and interdependent; our actions ripple out into all aspects of nature. Death is part of life and should remind us of our kinship to other animals. Yet our intelligence also imposes a moral obligation to seek understanding (through science) and to preserve the planet for future generations.

Consider the story of Agnes. She’s 72, a retired science teacher who recently lost her husband after an agonizing battle with cancer. Agnes grew up a strict Catholic in what she calls “the Polish ghetto of New York.” Her family ran a bar, and there was violence and sexual abuse that was always kept a secret. “One of the mortal sins at that time was eating meat on Friday or not going to church. Then one of the venial sins was lying. As a six-year-old, I was saying to myself that there are people in my family that lied, and it caused horrible things to happen. If I eat meat on Friday, I haven’t done anything to anybody. If I don’t go to church, I haven’t done anything to anybody. That seems stupid.” Yet it took over a decade for doubt to turn into rejection of her faith and family.

Agnes left New York to attend graduate school in chemistry in California, then married and had two children. After discovering that her husband had cheated on her for years, she divorced him and raised the kids by herself. She was in her mid-60s when she met her second husband, Tom. They had seven happy years together. “He was an amazing man. It was an amazing relationship.” Then he was diagnosed with advanced-stage cancer. When surgery and radiation failed, they spent much of their savings on alternative treatments. When Tom died, Agnes said, “It was stunningly shocking to my system.” Agnes is still grieving, but she does not despair, nor does she feel any inclination to return to the Catholic faith. Instead, she draws meaning from her scientific training to articulate an explanation of her place in the universe that is both rational and moral.

The way Agnes tells her story reflects several characteristics common to science narratives:

Mapping the past: Science narratives tended to explain life in terms of material causes. Looking back at their lives, respondents often spoke of good or bad luck, of random events of nature, of winning (or not) a genetic or social lottery that shapes one’s ability to make good or bad choices. As Agnes put it: “Hurricanes, tornadoes, the family you are born into. All kinds of things are random and can wreak havoc with us, and we have absolutely no control over it. The only thing we control is our reaction. Every decision we make determines the consequences that happen to us. I don’t think that there’s anybody micromanaging anything.” She doesn’t blame anyone for the hardships in her life, explaining “it’s what I had to go through to become who I am now.” There is a harshness in this outlook because nature isn’t fair. But there’s also beauty in randomness that can evoke awe at the unexpected. Agnes feels that Tom’s sudden death helps her pay attention and find joy in little things she previously might have missed. “Now I hear a bird sing in the garden and I just sit there and listen.” Like several of my respondents, she spoke of the butterfly effect (how a butterfly flapping its wings in Chicago can set in motion a chain of atmospheric events that cause a tornado in Tokyo). For her, this is at once a metaphor for the power of small changes and for the limits of our control over the world.

Mapping the future: From a natural science frame, death is the end of individual existence and consciousness, and my respondents often imagined it as analogous to experiencing anesthesia before surgery. And yet life goes on. Our bodies are recycled and nourish future plant life. In Agnes’s words, we “are composed of our physicality and our energy . . . like with anything on this planet that dies, our atoms and energy are recycled back into the universe.” If we have children, our genes live on through them. Agnes loves watching her two grandsons. “I am just amazed how much energy he has, he is so much like Sean [her son].” And our legacy is the impact we have on others, through caring for friends or family or by political organizing. For Agnes, that means volunteering for local election campaigns and committing to planting “only natives” in her garden.

Perceiving themselves as part of nature, rather than created by God in his image, led respondents to a place of humility.

A moral universe? Atheists are often portrayed as arrogant because they don’t acknowledge a higher power,22 but I generally found the opposite to be true. Perceiving themselves as part of nature, rather than created by God in his image, led respondents to a place of humility. The prevailing view about science (by nonscientists) is that it is neutral to morality, but I found that most individuals who relied on this narrative tended to see it as imposing a moral obligation. To quote Agnes one last time: “We have the power to influence the direction of evolution by the choices we make. Humans may be at the top of the food chain but now we have overpopulated the world . . . and we’ve done so many things that are so destructive. I think our purpose now should be to try to make this world livable for future generations . . . at this point in history, that’s what our whole goal should be.” The science narrative gives a sense of moral urgency to what respondents felt they should do with the time they have remaining: to show love for their friends and children, to appreciate nature or art, to be engaged politically, even as they may become increasingly physically disabled.

There were other types of narrative themes besides science, but they generally appeared in combination with it, and space does not permit description of them here (you’ll have to wait for the book!).23 But the data I’ve gathered thus far suggests that the foxhole theory (fear of death pushes us toward religion) is wrong. Instead, awareness of death pushes us to find meaning, and secular sources like science can be as rich a source of meaning making as religion is.

Religion is often touted as the only way to address the fear of death, but perhaps it’s just the oldest and most popular. What I’ve found significant about these generic secular narratives is how well they work to give meaning in the face of death. Secular meaning-making maps are actually quite similar to religious ones, at least in structure and function: they build coherence and control, they place human experience in relation to something bigger than ourselves, and they lend moral significance to our lives as we face its inevitable end.

They are different from religious narratives in key ways, too, in their materialist conception of life and their social constructionist view of meaning. By materialist conception, I mean the way that people rejected supernatural notions of a spirit or soul that survives death in favor of a scientific view that consciousness is located in the brain. While parts of us may live on (in the sense of genes passed on to our children or an energy that goes back into the universe), respondents did not think they, as individuals, had continued existence once the brain was dead. By social constructionist, I mean that to deny that there is any inherent meaning in the universe leaves it up to human beings to create meaning and purpose in our lives.24

And yet, it is not just the secular who create their own meaning. The way that people mix and match from various sources should make us rethink the boundaries between “religious” and “secular.” When an atheist finds meaning in Buddhism, is that religious? What about someone raised Catholic who finds that Mass calms her, even as she rejects belief in God or the afterlife? There is a small but growing number of scholars exploring how people build their own meaning systems from a variety of cultural resources, both religious and secular.25 I hope there will soon be more.

A few months before my uncle died, I called to tell him about the study I was conducting. He had always been a private man, so I was surprised and pleased when he offered to participate. We did not get around to it. By the time I visited, the cancer had entered his brain, causing swelling that made him hallucinate, and he was clear only for short periods of time when the nurse injected him with steroids. So I remain skeptical that he was talking to God on his deathbed. His caregiver was a Pentecostal Christian who was inclined to interpret whatever he said in religious terms. I am grateful to her for being there so he did not have to die alone. But I will always wonder how he would have told his own story.

Notes:

- Sheldon Solomon, Jeff Greenberg, and Tom Pyszczynski, The Worm at the Core: On the Role of Death in Life (Random House, 2015).

- Eben Alexander, Proof of Heaven: A Neurosurgeon’s Journey into the Afterlife (Simon & Schuster, 2012).

- Pew Research Center, Religious Landscape Study, Religion & Public Life (Pew Research Center, 2014), www.pewforum.org/religious-landscape-study.

- Vern L. Bengtson et al., “Does Religiosity Increase with Age?” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 54, no. 2 (2015): 363–79.

- For an expanded discussion of this literature, see my article “Meaning Making Narratives among Non-Religious Individuals Facing the End of Life,” in New Dimensions in Spirituality, Religion, and Aging, ed. Vern L. Bengtson and Merril Silverstein (Routledge, 2019). Some material presented here was adapted from this article, and from a talk I gave in Rome (“The Culture of Unbelief, 50 Years On,” Pontifical Gregorian University, June 2019).

- B. Woźniak, “Religiousness, Well-being and Ageing: Selected Explanations of Positive Relationships,” Anthropological Review 78, no. 3 (2015): 259–68.

- In the United States, this is a major public health issue. Those who are caring for an ailing life partner (especially if they feel powerless to alleviate their partner’s pain), or who lose their partner, are at increased risk for depression.

- K. Hwang, J. H. Hammer, and R. T. Cragun, “Extending Religion-Health Research to Secular Minorities: Issues and Concerns,” Journal of Religion and Health 50 (2011): 608–22; S. Weber, K. I. Pargament, and M. E. Kunik, “Psychological Distress among Religious Nonbelievers: A Systematic Review,” Journal of Religion and Health 51, no. 1 (2012): 72–86.

- Peter J. Wilkinson and Peter G. Coleman, “Strong Beliefs and Coping in Old Age: A Case-based Comparison of Atheism and Religious Faith,” Ageing and Society 30, no. 2 (2010): 337–61.

- Peter G. Coleman and Marie A. Mills “Uncertain Faith Later in Life: Studies of the Last Religious Generation in England (UK),” in Bengtson and Silverstein, New Dimensions in Spirituality, Religion, and Aging.

- Bethany T. Heywood and Jesse M. Bering, “ ‘Meant to Be’: How Religious Beliefs and Cultural Religiosity Affect the Implicit Bias to Think Teleologically,” Religion, Brain and Behavior 4, no. 3 (2013): 183–201.

- A. Gockel, “Telling the Ultimate Tale: The Merits of Narrative Research in the Psychology of Religion,” Qualitative Research in Psychology 10 (2013): 189–203.

- Ann Swidler, “Culture in Action: Symbols and Strategies,” American Sociological Review 51, no. 2 (1986): 273–86.

- Pew Research Center, Religious Landscape Study.

- Anna Sun’s wonderful article about this very problem appeared in the Spring/Summer 2019 issue of Harvard Divinity Bulletin, “Turning Ghosts into Ancestors in Contemporary Urban China.”

- Christel Manning, Losing Our Religion: How Unaffiliated Parents Are Raising Their Children (New York University Press, 2015).

- For example: Tim Clydesdale and Kathleen Garces-Foley, The Twenty-Something Soul: Understanding the Religious and Secular Lives of American Young Adults (Oxford University Press, 2019); and Vern L. Bengtson et al., “Bringing Up Nones: Intergenerational Influences and Cohort Trends,” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 57, no. 2 (2018): 258–75.

- To protect the privacy of respondents, names and identifying details have been changed.

- Organized Secularism in the United States: New Directions in Research, ed. Ryan T. Cragun, Christel Manning, and Lori L. Fazzino (de Gruyter, 2017).

- Penny Edgell et al., “Atheists and Other Cultural Outsiders: Moral Boundaries and the Non-Religious in the United States,” Social Forces 95, no. 2 (2016): 607–38.

- E. H. Ecklund and K. S. Lee, “Atheists Negotiate Religion and Family,” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 50, no. 4 (2011): 728–43.

- Edgell et al., “Atheists and Other Cultural Outsiders.”

- The personal growth movement (including 12-step programs, mindfulness, Landmark Forum, and the like) has become an important source of meaning for many secular people. Several individuals drew on Buddhist themes as a nontheist framework for meaning. One man’s narrative was framed by Marxism, another’s was steeped in transhumanist concepts.

- These narratives may be a good fit with our society’s celebration of individualism, the belief that we should have the freedom to choose our own meaning system, a framework we might call the narrative of choice. Manning, Losing our Religion.

- Penny Edgell at the University of Minnesota and Ann Taves at the University of California, Santa Barbara, are two examples of this trend.

Christel Manning, Professor of Religious Studies at Sacred Heart University, has spent the last decade studying people who leave religion. Her book Losing Our Religion: How Unaffiliated Parents Are Raising Their Children (New York University Press, 2015), received the 2016 Distinguished Book Award from the Society for the Scientific Study of Religion. Manning’s current research, supported by a grant from the John Templeton Foundation, examines how nonreligious individuals find meaning as they approach the end of life.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.

Thank you for researching and writing this article. I found comfort in it, and in most of the comments. I grew up in Baptist and then Pentecostal churches. At a very young age I was taught to fear hell and the devil and it warped my childhood and young adulthood. Great emphasis on the blood sacrifice of Jesus and suffering. Things started to NOT make sense. My begging god to forgive was ignored, as far as my anguished-self could tell. I’m now 67 and I’m an atheist and this is what I’ve learned through logic: if a god existed and wanted anything to do with humans, it would give clear communication to all about what was needed and expected and there would be ONE religion instead of thousands. If an almighty god existed, why is the onus on humans to “find” him, since he supposedly has all the power? A test doesn’t make sense. Also I finally read the bible and the god of that book is horrible with the exception of the cherry-picked verses I was taught to focus on. Innocent blood sacrifices from animals and then Jesus? What kind of god wants that? I’ve also since stopped believing we exist after death because the brain can be damaged and/or manipulated (drugs/surgery/accident), either erasing or changing who a person is. If we existed separate from our brain, we’d remain the same.

My belief as a Christian is that God has our life on earth as a ‘test’ to allow us to come to a decision of our own volition whether to be with him or not. Obviously it follows that I don’t believe in a literal hell where people are tortured forever, but that the ‘hellfire’ just causes the person to stop existing forever. I also think that one can attain salvation without coming to believe in the Christian god, since not all people have such an opportunity, but that the decision God comes to as to where that person will go will be just based on how that person feels (I obviously also then believe that he knows every aspect of us in order to make that judgment). I’ll be honest a lot of the old testament feels really iffy to me but I think a lot of what happened back then was just the way life was. God meets us where we are, and if society was all about sacrificing animals then obviously he’d be chill with people continuing to do that. I don’t believe animals have souls or a consciousness in the way we do, so like while torturing animals is bad, I don’t think killing them to eat or sacrifice is bad in the way it would be with a human. What you said about one’s personality being altered due to drugs and surgery is very interesting btw but the way I think about that is there is a way that God created each of us, but we can change from that either just naturally through life or through these traumatic events. That doesn’t change the way God created us to be and I believe that a big part of the purpose God has in our lives here on earth once we enter into relationship with him is gradually returning us to that. I also think that once we die and go to heaven we will return to that anyway but the point of doing it on earth is simply the satisfaction it would bring the person.

(I am 16 btw sorry if my beliefs are a bit all over the place I’m working on it)

why didn’t god ” provide a way ” to not fear death + what IS the way ??

why did god make us HUMAN so were CAPABLE of fearing it

does anybody else have this thought ?? // am i the only one ??

I don’t think you’re the only one but many people, myself included, don’t have this thought because there most likely isn’t a god to expect this from. Death is just an unavoidable part of the processes involved in life coming about and continuing to reproduce. Death is not a bad thing, it’s not out to harm us, so there’s no need to fear death itself. I do fear not living my life as fully or as well as I’d like though. But all I can do about that is try my best and see what happens 🙂

Darian, I have come to believe that death is to serve, emergently or by design, as a return to sender — in which one who humbles themselves and submits to the big picture of life, and the Almighty Divine of whatever religion they hold value in, find peace in the end of life and may either emotionally or literally find paradise in those final moments as they’re bridged to something bigger in death.

Those that suffer until the very very end, simply resist some aspect of these truths due to final attachments they are not yet ready to let go. This does not mean they are doing anything wrong, it is to be expected, but it does not mean they are doing everything right — in the end, we grow confused, and at the final wordless moment of death many finally come to terms and find their paradise, but some may very well be trapped in an inner mental “hell” of their own making, of their own regrets and memories.

Thank you for this, which resonated for me on every level.

**I think of my death as recycling and, as I age or even as I wake up each day, I aspire to be compost rather than a styrofoam cup.**

I see all sorts of death doula and end of life counseling programs and trainings and I would very much like to learn more, do more, and down the line, be more hands on with providing end of life (not my phrase but…) care to others. But most programs seem grounded in spiritual belief networks. So I don’t know where to begin. I will still seek these programs, but very much like those interviewed, I just don’t feel faith in an afterlife is NECESSARY for a positive approach to dying and death or what this article describes as mapmaking— a very good word.

Any resources or discussion groups or programs — I welcome suggestions on this thread.

I’m a non-religious death doula, and also training to offer “spiritual care” in hospitals. Spiritual care or health or wellbeing does not have to include any kind of supernatural beliefs, it is about how we makes sense of our lives, the meaning we find, the stories we tell, all of which in my case are grounded in a scientific understanding of the world and my experience. No spirits or gods required. (But I can support people how do use those narratives too.)

I may only be 12, but I have always had the occuring fear of death every night before i fall asleep. When i tell people about this, they say, “Why? are you dying?” i reply with ‘no’ and having this stupid fear was overcoming me. My stomach would flip, my heart would race, my body would become warm but i would get goosebumps. I would end up running to my mums room for comfort. It came to the point where my Christian friend would try to comfort me by telling me about her religion. She must’ve thought it was helping me. But it was making me more confused and scared. My best friend just happened to be Muslim too. So now I would have this fear and no one was helping. Until my mum went on a trip. it was yoga, meditation, and all that kinda zen stuff. when she came back she told me all about it. And she told me that she got to peek into the spirit world and saw she was an Indian Princess in her past life or something. (sorry if you have a religion, you dont have to belive me.) I was violently shaking with this overwhelming feeling of excitment and a little happyness.

Continued:

This lasted me a while. This feeling was great. Until my brain started messing me up. I had just seen a TikTok about how sleep is a temporary death. This scared the crap outta me. (And i never grew up with a religion.) The idea of losing my little voice inside my head telling me what to do every day scared me. I needed that. (oh gosh I’m actually shaking as i write this right now. Not of fear though.) So i searched up, ‘What happens after death if i have no religion?’ this website came up and i clicked it. I read the entire thing and some of the comments. I feel a lot better. I don’t feel I’m gonna have to worry about this anymore. I’m really happy I found this website. It may not have given me a straight up answer, but i feel more stable.

In the United States, 97% of scientists who are members of the National Academy of Sciences are atheists. While only 3% of the prison population are atheists.

I don’t need a religion to help me face death nor justify or give meaning to my life. I feel there is a probability of nothing after life and I 90% can deal with that. Only, two significant occurrences have left a mark on me, that are disruptive. I would like to have a conversation with you or someone like you -not just to help with my remaining 10%, but hopefully to offer you some additional insight. I am 74 years old and have lived an adventurous life with quite a bit of life experiences. Would very much appreciate your reply.

Donna McCracken

I am surprised that most of the nonbelievers don’t emphasize the role of friends and family when searching for meaning.

How Camus faced death is really astonishing. Although I’ve gotten really anxious during this covid time especially being a Chinese death is something that has gripped me and I’ve been surrounded by fear.

DR.Manning,thanks,beautifully explained & expressed .death is a place to be at peace.For me religion means broad minded.Feeling the presence of God in every human being.We all are connected by God & children of same Almighty.For me God exists,surrender to His will & focusing internally to search our actions. Ethical values & clear conscious must be there.All religions are good,so far not too extreme.For me treat others with dignity is the best religion.

You may try reading up on Advaita (Non-dual) philosophy.

Has your book been published on this study and if so, what is the title?

I´m not sure why would you mention “𝐫𝐞𝐦𝐚𝐢𝐧 𝐬𝐤𝐞𝐩𝐭𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐥 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐡𝐞 𝐰𝐚𝐬 𝐭𝐚𝐥𝐤𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐭𝐨 𝐆𝐨𝐝”. If you were an atheist you wouldn´t be skeptical but 100% sure that he was hallucinating.

He was skeptical about whether or not his atheist uncle was talking to god in his final moments even though he never believed in god

Trevor: came across your article, as I was looking for information about “lack of hope around death for those without a Christian belief ( 1 Thessalonians 4:13). It would seem today’s “unbeliever” has better ways of framing a story to give them some sense of life and death as compared to the ancients.

The hope Paul describes seems to be lost in the lives of many who have rejected religion (not surprising) because of the many ways churches have distorted the hope and love that Jesus exemplified and taught.

I appreciated the insights that others shared in their comments.

Hope your

Hi- I googled this exact phrase as I am currently struggling with this concept. I cannot fathom no longer existing yet I know I will one day. I’m only 30 and would statistically have plenty of time to worry but I also cannot stand the thought of never seeing my parents again. I want to become the person who uses this to make life more precious and make every moment count. Trying to figure out how to do that. Where are you in the journey?

Beautifully written, the passing away of my grandfather brought me here. As a atheist I can only attribute death to absence of consciousness which sounds very ambiguous and vague, but I found that only way to overcome the grief was to just believe that there’s a better place (which also doesn’t make sense because if there’s a better place then what are we doing here) and stop thinking about it. This really helped alot at the time. But now I’m pondering upon a more digestible explanation. Also I feel like, religion is more of a dictatorship, you just follow without questioning and pointing flaws.

I am a humanist and belong to a Unitarian Universalist Church. I have no concern about any meaning the universe may have. My concern is with ethical behavior among humans. That’s all we have any control over. I am ninety years old and have recently suffered a stroke. Like many others I don’t fear death but simply hope that the process of getting there is not too unpleasant.

I am sorry about your stroke. I don’t know what effects it has had on your physical abilities, but you can clearly articulate your thoughts. That may or may not be a gift for you. I only halfway believe you when you say you don’t fear death. I am a lifelong nonbeliever, and behaved very recklessly most of my life. I am now 61, and last year my 24-year-old first responder son shot himself in the head while living out of his car. He wanted desperately to be a part of something universal and loving, but when he died (not passed, a term I despise), the fire department sent out its troops to stand there and salute, but none of them came to talk to me. Not one of them — and they knew him. That is not ethical. That is not kind. He died alone and lonely and desperate, and he was 24 years old and looking to figure out what it means to be a man. He died almost a year ago (March 19, 2020) and I am facing that marker. When I told the funeral director that he was an atheist (as am I), the look I got could freeze a match.

I hope that you have loved ones around you. I am an epidemiologist, and I have come to believe that the strongest factor in a satisfying life (and death) is social support. My grandfather saw it coming, and died peacefully in his loving wife’s arms. That is a good way to go.

I am 37 guy with one child in New Zealand. You expressed your fear/hope that the process of death is not too unpleasant. We are all the same with that feeling of powerlessness in facing an unknown. All the same I like to hope or think that the big bang was set in motion by some intelligence from another universe and space time. Its not much consolation as ‘it’ might not have the even the knowledge of us but i hope it does. Here is my best effort at grandiose comfort at death: You/I existed in a space and time. That means you/I exist eternally since time is viewable at all times from another perspective. Your life time is the part of you that gets to interact with others. and your pre birth and death time is your dormant inactive part of space time. But you still had an impact on the whole huge story of humanity- possibly before you were born even due to how time and space and gravity interact. Death is only the end of the ethically intense interaction phase. The agency we had at being able to say and do what we like and when we like, was not the point of us – the point of us was to be what we were, and think how we thought.

Thank you for this. I am 22 years old and have been an agnostic atheist for a few years, and have recently been having a bad bout of death anxiety and have decided to confront it head-on. Although I am still quite young, recent events in my life and around the world have made me realize the sobering fact that death can come at any moment in many forms. That being said, this article has given me some comfort, and I have come to realize just how lucky many of us are to be alive, and how we should not squander our only moments in life. I still struggle at points, but it’s comforting to know we’re not alone when it comes to death, and we should strive to make an impact to improve the world around us and ourselves, in whatever way we can.

By definition god is omniscient, omnipresent, and omnipotent. Such a thing could not be missed, and if there is no way to observe a creature with these faculties, there is no philosophic position as “agnostic”. You can’t be on the fence about the existence of such a creature if you accept the given definition. Give up agnosticism and accept the only remaining choice: atheism.

I am an atheist, and I just wanted to identify myself as such. Maybe we ought to have an atheist ‘registry’ somewhere, so that your research can be done more easily! (I know; nobody wants to repeat research that they have already completed.)

My problem is that, at the end of our lives, there is no easy tradition which friends and family can follow. I don’t know where to look for inspirational verse or prose, to replace what is read or spoken in Christian funerals.

Hi Archimedes,

While no inspirational verse or prose or secular ritual you can use comes to mind, I am wondering if you could write something to be spoken at a memorial service. While I can not speak for others, I think that if I were to hear something that an atheist friend or family member wrote about what brought them joy in life, how important family and friends were, etc then I would feel a sense of comfort in grieving their death.

I am a scientist and an atheist. I am surprised that most of the nonbelievers don’t emphasize the role of friends and family when searching for meaning.

the scientific narrative took a lot of inspirations from stoic philosophers.

I am an agnostic searching for a structured eternal life in science. That conciousness exists outside of the body and our personal consciousness exists in a sort of Star Trek “Borg” appeals to me, I’m just searching for the science to rationalize such a philosophy.

You may try reading up on Advaita (Non-dual) philosophy.

Thanks, Dr. Manning. I found your article through a Google search. I might be guilty of being one of those “arrogant” people who feel just a wee bit superior sometimes to those who rely on religious crutches to get them through tough times like this coronavirus situation. Except I’m not feeling arrogant at all these days: I envy them their blind faith, even as it is impossible for me to subscribe to it. Thus I find myself wondering how I’m going to handle the end of my life, should it come unexpectedly, in a dignified, peaceful way, as well as how to live the rest of my life without fearing death. Your research and conclusions are very helpful.

I ve just finished reading the outsider. how Camus face death is really astonishing. Although I’ve got really anxious during this nov covid time especially being a chinese when death is something gripped me and surroundings by fear.