Featured

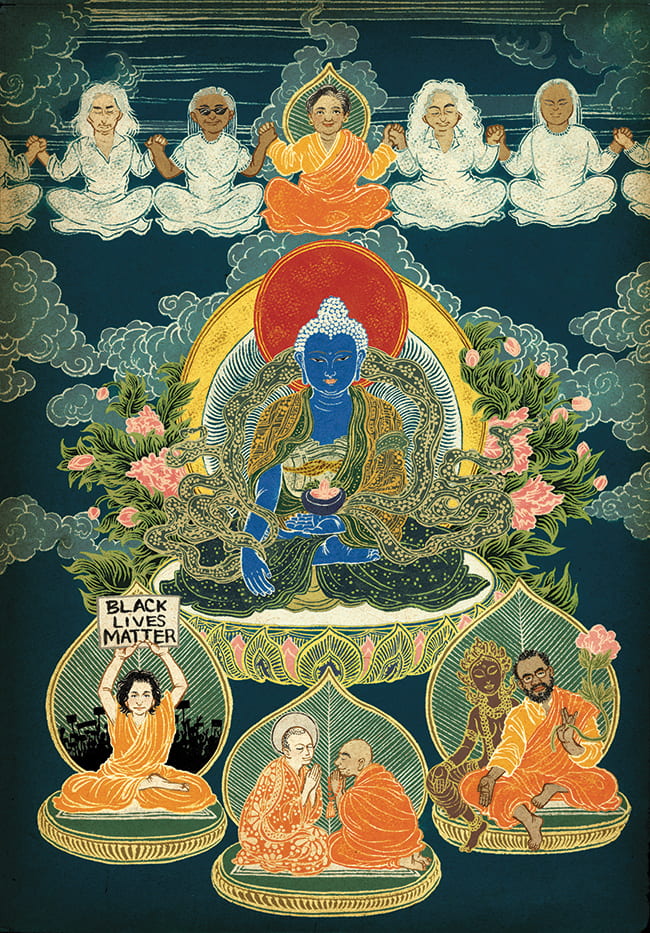

#BlackLivesMatter and Living the Bodhisattva Vow

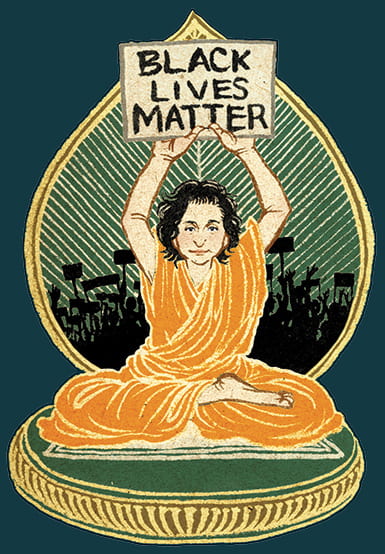

Illustration by Yuko Shimizu

By Christopher Raiche

Soon after Michael Brown’s murder in Ferguson, Missouri, my news feed lit up. While Brown’s blood still soaked the street where his body had been left in the hot sun for hours, friends, colleagues, and strangers posted incessantly on Facebook, outraged that yet another young and unarmed black man had been shot dead by a supposed protector of the peace. What was uniquely horrifying to me, however, as I read and reposted information about Ferguson, was that I was not outraged or sickened, not really. Instead, I was performing a progressive ritual of sorts. By sharing links and framing taut sentences of protest from the safety of my Cambridge apartment, I was spinning an image of myself as a Harvard Divinity School–educated “good one,” in solidarity with the oppressed everywhere. But this was an image no more substantial than the pixels that flickered to form it. When I caught myself in this arid performance, a deep nausea began to stir inside me. I became aware of the cruelty of using actual suffering as an ornament to my identity as a caring white person.

My digital avatar has a fine polish, the sheen of a sensitive Buddhist. But as the hollowness of my enactment of solidarity has become more evident to me during the past two years, that self-image has eroded. A crack has appeared in the veneer of all my performances of care, initiating a meditation on emptiness like no other. I have begun to question how this maneuver had remained so hidden from my awareness, despite years of committed Buddhist practice. How have the teachings I have received, and perhaps misunderstood, sheltered me from reality?

I have studied “emptiness” for nearly twenty years. I have studied emptiness as an exploration of the reality of interdependence. I have studied emptiness by meditating on the illusion-like, ephemeral, and insubstantial nature of all appearances. This study has been sincere, but I have begun to interrogate the ways I have used the doctrine of emptiness to blunt my perception of racial injustice. I have begun to see the ghost of an errant emptiness haunting my own heart and the Buddhist community in which I live. After Ferguson, the majority of my mostly white sangha seemed conspicuously untroubled by the increasing visibility of mass black death and racial terrorism in the United States, while also conspicuously demonstrative of a polite yet detached concern about injustice.

The doctrine of emptiness can be applied as a temporary salve to lessen the discomfort of facing systemic racism and other injustices. The sublime Buddhist teachings of liberation can be co-opted by white privilege and used as a shield against reality, rather than as a sword for cutting through self-deception. Meditation practice can uncover the painful realities of our intimately interconnected lives, unlocking genuine compassion, but meditation can also be bent to enable those privileged enough to ignore such realities with yet another means to look away. Do practice centers help us to hear the cries of each other and the world, or do they provide soundproofed havens, false refuges from the disturbing chorus of such cries?

With painful honesty, we must assess what our practice centers are doing and who they are for. In the United States today, Buddhist teachings on emptiness, compassion, and universal liberation risk becoming yet another brand of spiritual ornamentation for a privileged class. How might the Dharma in this country mature into a force for greater compassion and action, a force for radical social healing and justice, and resist being co-opted as yet another means of self-therapy for the most affluent strata of society? Insight into emptiness should make us more aware of collective suffering and empower our potential for collective awakening. To foster this potential, we need to teach the Dharma in a new way, exploring what emptiness and compassion mean in terms of our collective life within a social body, a body held together by an institutional fascia of structural racism, inequality, and suffering.

Illustration by Yuko Shimizu

In various public talks and private interviews, when I and other students have posed questions about injustice to white Buddhist teachers, both male and female, I have witnessed two consistent, now predictable responses. First, the questioner will be told that greed, aggression, and delusion (the “Three Poisons”) are resident in all of our hearts, and that we need to attend to these in our own private practice. Second, and especially when questions involve issues of identity—racial, sexual, or religious—the genderless, colorless, nonconceptual nature of our “true self” is invoked. Both of these responses sidestep the structural dimensions of greed, aggression, and delusion and their very real material and psychological effects.

These teachers are kind and well-meaning, and their responses may indicate the unique challenges of adapting the Dharma to the United States rather than any willful ignorance. But though these two standard answers hold a kernel of truth, they often shut down a questioner and shut out the complexity of living in an inescapably relational world, one saturated with structural evil. An appeal to personal practice, though an integral part of the process of liberation, may also reveal the residue of an American liberal individualism, clothed in Buddhist terms. The senior teachers, administrators, and boards of most of the dharma centers I have trained within during the past twenty years have been conspicuously white and middle class. However sensitive and engaged these leaders are, the demographic reality of these centers contributes to which lived realities are given priority and voice. From the default vantage point of a largely invisible whiteness, it is to be expected that the effects of an ongoing white supremacist history are left largely invisible and unspoken.

An appeal to“true self,” or Buddha-nature, that is blind to race and identity can all too easily redirect attention away from the very real suffering out of which a questioner may have courageously spoken. Answers that stress emptiness and personal practice also downplay our mutual responsibility to deconstruct racial fictions and to help each other heal from the deep wounds left in their wake. At best, these “Buddhist” answers may inspire a sense of personal resolve or offer a glimpse into a life free of limiting definitions; but, at worst, they reinscribe a mythology of individualism and support liberal colorblindness, two particularly crass delusions masked in “enlightenment.”

The meditation hall is part of a larger, shared world. It is cautioned in Buddhist circles not to abide in a mere acceptance of emptiness, either as a doctrine or as an experience. Yet within many Buddhist sanghas, such abiding is indulged. Meditation can become a mode of escaping into ignorance and abstraction, a sham version of the living quality of “Don’t Know Mind,” as Zen master Seung Sahn called it. Genuine Don’t Know is a state of vivid fullness, as we experience the particularity of each moment.

This living Don’t Know is responsive, whereas its dull doppelganger is merely a glorified stupor. If we grow attached to a hollow self-state posing as emptiness we arrest our progression from an open, empty mind toward its expression in compassionate action. This dullness, as it plays out in our social body, is often a function of privilege. If we are privileged enough, we can choose to throw up our hands and say “I don’t know” when faced with a world that demands our compassionate response. This evasion of responsibility can manifest as a turning away from rather than a turning selflessly toward social suffering. This faux Don’t Know contains within it an implicit “I would rather not know.” It is the opposite of waking up.

The horrifying residue of slavery’s brutal history lurks in our national consciousness and is still enshrined in our country’s policies. We may also be aware (at least subconsciously) of our nation’s ongoing imperialist projects exploiting the labor and lands of darker peoples around the globe. This painful legacy and its continuation must be honestly addressed if any insight into “interdependence” among American Buddhists can be “insight” proper. Racism goes beyond mere personal prejudice and bigotry; it is a systematic negation of the full humanity of certain people. It is a violent negation of life based on an utter delusion, yet this delusion has very painful and concrete effects on the social mobility and well-being of people of color. This process of negation truncates the lives of those who “benefit” (at least materially) from it. By denying the full humanity of nonwhites, even subliminally, and projecting our own shadows onto the “Other,” white people like me relegate ourselves to an anxious, fictional world of dishonesty, denial, and self-induced paranoia. This produces not only social isolation but internal fragmentation.

When confronted with the painful realities produced by white supremacy and the corresponding suffering that plays out within and around us, we must resist escaping to “nowhere.” When we don’t know how best to respond to a situation, it is best to listen closely, with humility. This is a Don’t Know Mind which puts us in touch with each other and our world. Part of what we become intimate with when we open to reality is the systemic abuse of our brothers and sisters. Race may be a fiction, but it is a visceral fiction, with painfully real effects. This fictive but real quality requires our collective attention as we seek to disentangle our consciousness and our bodies from it. Racializing whiteness places whites in a continuing story of racism and violence that most of us would rather exempt ourselves from. Embracing our complicity in racist categories (including that of “white”) may provoke the realization of a living emptiness, helping enlightenment to take place, whereas denying historical processes encapsulates us in a disembodied, privileged bubble. To this point, Hannah Arendt writes:

Those who reject such identifications on the part of a hostile world may feel wonderfully superior to the world, but their superiority is then truly no longer of this world; it is the superiority of a more or less well-equipped cloud-cuckoo-land.1

This speaks to a dangerous misunderstanding of “emptiness” currently playing out in predominantly white convert communities. Many sanghas run the risk of becoming “more or less well-equipped cloud-cuckoo-lands,” avoiding the realities of our history and our present with appeals to an “ultimate” truth that obscure our complicity in systemic racism and injustice. In the guise of profound teachings on emptiness and Buddha-nature, whites can preserve the invisibility of our whiteness and the unearned privileges attached to it. In Zen literature we read that airs of “ultimate” truth can be mere posturing, the “stink of Zen.” The Zen tradition, known for its sharp, humorous irreverence, often undercuts its own claim to anything special, calling its own aura of holiness “stinky.” But the stink of false consciousness is currently offered on our altars as if it were fine incense.

There is every risk here of reducing Buddhism to a bourgeois exercise in privilege maintenance, a “spirituality” that alleviates, in a palliative rather than a curative way, the uneasiness that vibrates through our dysfunctional social body. We should not perfume this body, but address its wounds. Identities that have been marginalized in a white supremacist culture need to be heard and honored. Teachings that negate identity in the name of emptiness can seem out of touch, if not hostile, to nonwhite visitors to majority white Buddhist centers. The well-meaning focus on increasing the diversity of sanghas may be missing a larger point, one that challenges the very way the Dharma is being practiced and taught in this country.

This expression of compassionate insight does not turn away from the realities of this world.

Last year at the height of the Black Lives Matter protests, upon hearing helicopters overhead, I often closed my laptop or broke from a formal group meditation at my sangha, hanging up my robe to put on a coat and join the millions marching in the streets nationwide. Walking down Massachusetts Avenue in a multi-racial mass of people was a vivid illustration of what embodiment as care might look like. Acting as a body of care, a body of solidarity, we held our hands in the air, chanting “Hands Up, Don’t Shoot,” the last words of Michael Brown. As a collective body we would “die,” blocking the major intersections of Cambridge, lying in silence for four minutes and thirty seconds, in memory of the four hours and thirty minutes Brown’s body lay in the street after his murder.

These events evidence a kind of massive, interconnected, yet not strictly identifiable “body” functioning in terms of the identity of one young black man—echoing his last words, his last gesture, his murdered body in the street. Such events are a manifestation of a kind of rupakaya, or “form body,” that transcends the binaries of one and many, identity and nonidentity. In Tibetan Buddhism, rupakayas manifest the Buddha’s formless compassion in bodily terms, terms which deluded beings can then perceive and learn from. I believe that political demonstrations are a form of rupakaya, our collective wisdom and compassion creating a visible form of insight that poetically illuminates a profound truth—in this instance, that the abuse of one man in Missouri can tear at the living fabric of us all, and that a massive, diverse group can embody and reflect the suffering of one man and the abuses of a broken system. This expression of compassionate insight does not turn away from the realities of this world and does not retreat into any nominal emptiness. It is because we are empty of an isolated, strict selfhood that we can manifest as a body of care, solidarity, and fierce compassion. This is an expression of a living emptiness, far from any abstract negation.

If the bodies of law and government do not defend all of us and if our very “defenders” act as murderers, they and the cities that house them must be “shut down,” at least symbolically. Such action reinvigorates our living, collective flesh. If these abstract bodies are to be bodies of care and not bodies of violence, we must infuse them with the collective breath of our living flesh—breathing together our empty, luminous mutuality.

Over the past year, I have slowly excavated through my previously invisible whiteness, becoming disturbingly—yet necessarily—more conscious of the many unearned privileges that accompany my particular skin bag. While awkward, humbling, and at times disorienting, this has been a kind of birthing process, from a limited, delusive enclosure into a larger body of participation and mutual recognition. My former unconscious whiteness has been increasingly revealed to me as utterly empty, yet it perpetually recreates painful social and political realities. It is not enough, however, to acknowledge the emptiness of mental images and to leave it at that. It is possible to see the emptiness of one’s whiteness without actually letting go of it. One can even subtly preserve it with a new, ironic form of pride in one’s own insightfulness into “race.” We must continually see ourselves honestly, be embarrassed—and then go further.

As I have become more aware of the realities my whiteness once made me oblivious to, I have started to sense the contours of a richer, shared world. Greater pain and greater joy have accompanied this new awareness: the joy of reunion, and the pain of no longer living at a remove from realities that include massive systemic violence and injustice. My pain now seems to occur within a more capacious heart. I feel more pained and more peaceful, and I am aware of a fundamental ache, with far less paranoia, mental static, or brittle anxiety. It is perhaps what Buddhists call bodhicitta, an awakening heart.

In the course of this process, my compassion for whites and nonwhites alike has become more genuine and deeply felt. The daily abuses to body and soul in a white supremacist culture are now more obvious to me, even as I do not assume to know what enduring these abuses are like for the non-whites who suffer them. I am more intimately aware of how unconscious whiteness is a profoundly life-limiting affliction that constricts my experience of myself and others. My own experience of increasing ache and openness has made me certain that there is a way of understanding emptiness that can and should function alongside the work of challenging racist structures. Such an understanding of emptiness is rich with ethical implications for how we, together, might realize the Dharma within the terms of identity struggle, resisting the tendency to retreat into any safe “cloud-cuckoo-land” of abstractions about “nonidentity” or “ultimate truth.” A new articulation of emptiness needs our careful, collective attention.

There may appear to be a philosophical dissonance between the need for an affirmative assertion of identity and the core Buddhist insight of fundamental identitylessness. How might such positive assertions be skillfully embraced and lived out, while also holding to the Buddhist view of emptiness or nonself? Addressing this potential confusion is necessary for Buddhists now living in a multicultural, multiethnic, and global world. Privileging notions of an ahistorical, unconditioned freedom (nirvana) can deprecate material attempts to improve concrete living conditions as too concerned with the lesser realities of an illusory existence (samsara). When provoked to address the struggles of the oppressed, I have heard white Zen teachers say “mind makes everything,” or white Tibetan Buddhist nuns say “samsara will never be perfected.” These statements contain some insight, but I have also felt them to be attempts to diffuse a painful conversation that will make white practitioners palpably uncomfortable. To reestablish the fragile equilibrium, “pure” Buddhist teaching is often expounded, but a fixation on ultimate freedom obscures the necessity for working toward securing relative freedoms.

By cutting through our socially constructed delusions and exposing the hollowness of any faux “emptiness,” we can overcome our complacency and actualize genuine insight and compassion.2 We must actualize the fullness of emptiness, an emptiness that holds identities in openness and care, rather than collapsing them within the cold vacuum of an abstract negation. In white convert Buddhist circles, the defense of marginalized identities and modes of embodiment is given little attention, as the emphasis is placed on the reality “beyond” identity and body. There is no recognition that the freedom of reality’s living flesh might be realized through these very identities. By prioritizing teachings on the illusion-like nature of bodies, white practitioners run the risk of overlooking how caring for such bodies may be the very location of and occasion for one’sownspiritual growth. Such care may in fact be the ultimate expression of one’s deepening awareness and maturation on the Path.

Entering the fray of identity politics reveals the nature of living emptiness. Here, we encounter the empty fiction of race without shying away from its real consequences in our lives. Here, a contemplation on emptiness merges with a compassionate real world awareness that is capable of action. When we care for each other’s shared suffering and encounter one another’s particularity our bodies become a location for opening to emptiness. In such encounters, we are given the opportunity to wake up and witness the elusive, living people that have been obscured by our static mental images. These could be the ideal conditions for a true revitalization of Dharma.

Since May 2015, the Cambridge chapter of Black Lives Matter has organized monthly “Race Talks,” where a racially mixed group congregates to discuss a chosen topic—for example, reflecting on whose culture and history is taught and honored in standard school curriculums, and how this validates certain identities while making others invisible. After presentations and group discussion, we separate into smaller racial affinity groups to explore more personal dimensions of the day’s topic. Following this, everyone comes back together to share the emotions and thoughts that arose during the meeting. On the night we discussed school curriculums, there was a charged, urgent air when we reassembled. I began to reflect on the white male role models I had taken for granted, and the omission of comparable figures of color, and I suddenly had an acute sense of the magnitude of that omission and the oppressive weight that absence occupied in the bodies of the people around me. After the meeting, I was deeply moved when a black friend told me that until now he hadn’t realized how much he needed a space like this. I felt viscerally aware of the depth of the wounds this kind of dialogue addressed and of the necessity of the healing work we had embarked on.

These gatherings have been tender, challenging, and necessary. They hint at what a meditation into living emptiness might look like. I believe that these meetings provide a model for the kind of liberating group contemplation of emptiness-amid-identity that should be integrated into American Buddhist practice. Through deep listening and honest conversation, we can co-create an intentional environment that nourishes the possibility of a more genuine encounter with each other. Such encounters have the power to awaken us to the vastness of our shared life.

As we allow the fullness of each other’s emptiness to touch us, our capacity for fearless openness and care may be discovered to be boundless. Embracing identity can be a form of living emptiness through communion. Instead of feeling the ache of this world as a burden to be evaded, we allow it to touch us more intimately. Touching our living emptiness grants our experience an expanse in which to unfold without overwhelming us. Within this expanse we may embrace hardships without hesitation, and being so empowered, we can endeavor toward collective liberation. Progressively more exposed, no longer seeking false refuges, even in “pure” Dharma, we can awaken to a renewed appreciation for life.

In this ever-fresh tenderness, may our vital hope to actualize a more just world be realized. Humbly I have offered these young, forming thoughts, and now this simple prayer:

May we recognize the boundless Tathagata in each others eyes.

May we together shed the myriad veils of ignorance,

And witness through each other the intimate dawn of Awakening.

Notes:

- Hannah Arendt, “On Humanity in Dark Times,” quoted in Amy Allen, The Power of Feminist Theory: Domination, Resistance, Solidarity (Westview Press, 1999), 106.

- One voice I have found particularly illuminating is that of Womanist theologian Shawn Copeland, whose potent eloquence is good medicine for treating faux “emptiness.” In Enfleshing Freedom: Body, Race, and Being, Copeland states that within a white supremacist culture, where “black presence is absence and white presence is presence,” reimagining “full personhood” and employing new images of wholeness-in-community is an ethical requirement and a tactical necessity for an oppressed group’s survival, both spiritually and materially. Copeland cautions us that while our true life “transcends race, gender, sexuality, class, and culture, [we should] neither dismiss nor absolutize.” M. Shawn Copeland, Enfleshing Freedom: Body, Race, and Being (Fortress Press, 2010), 16, 18.

Christopher Raiche is a third-year master of divinity student at Harvard Divinity School. He is the Values in Action social justice coordinator for the Humanist Community at Harvard. As president of the Harvard Buddhist Community, he organized Harvard’s first conference on Buddhism and Race in America in 2015.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.