In Review

Words in the Blood

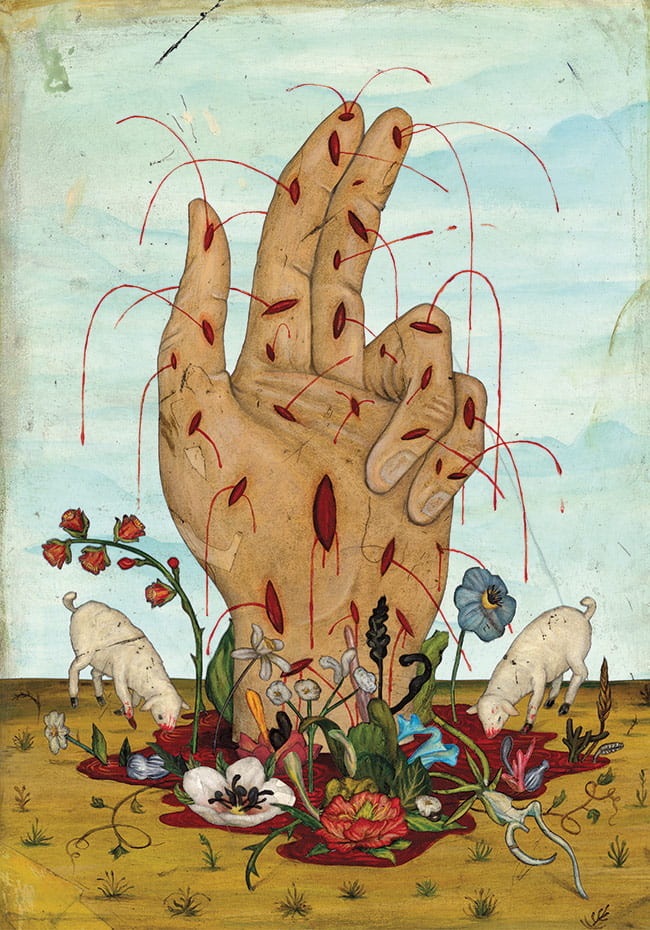

Illustration by Jason Holley

By Mark D. Jordan

Some academic books stop our rush to keep up with one field or another. They may be too unusual for skimming or too full of consequences. Blood Theology by Eugene Rogers is both. It is an inventive book on an unsettling topic: the circling of blood-motifs through Christian discourses, customs, and artworks. Rogers hopes to “make blood strange” for his likely readers so that they recognize how often Christians still appeal to it and how inconsiderately they apply it. If readers are tempted to dismiss older fascinations with blood as barbarous or pathological, Rogers can show how the old lives on in Christianities now preached. Christians cannot escape blood-language, cannot banish or erase it. Since we will continue to use it, Rogers urges, we ought to learn how to resist its dangerous impulses.

Estrangement-exposure-redirection is a familiar plot in books of academic critique. It is what authors often mean by “an intervention.” Rogers breaks open the clichéd plot to accommodate his deliberately confused and always risky topic. In Christian blood-language, he confronts dispersed, variable, and frequently automatic patterns of thinking. So, he distributes the book’s attention. Whatever the impression left by my first paragraph, Blood Theology cannot be summarized. (Please hear that as high praise.) Rogers cautions: “In this book I do not have a thesis. There are far too many for that. Rather I have broken out in theses. Centuries of theses. The theses may not even follow; rather they coagulate” (25). If theses behave strangely here, so do other ways of writing theology. Pursuing blood-languages demands invention—and cunning.

Rogers’s book does not investigate one archive but 20 or 30. It changes genres as it moves, becoming in turn ethnographic report, scriptural exegesis, social modeling, iconography, ethical critique, and speculation about prehistory. Fields or “disciplines” appear in unusual constellations. Rogers even changes his voice. On some pages, he shows his fluency in the clerkish styles of academic dispute. On others, he speaks aphoristically, in sentences stripped by almost poetic attention. Once or twice, there is colloquial directness: “Well,” he interjects after a lyrical flight, “that was grandiose.” Rogers is here embarrassed by a passage that ends: “Under the economy of God’s body, the separation and multiplication that spreads goodness is the Eucharist of Christ’s sacrifice” (72). “Grandiose,” perhaps, but also necessary. His lyrics are not slips. They are antidotes to the toxins of blood-language.

Blood Theology breaks open the standard academic plot to clear space for summoning blood-languages across times and places. Rogers brings them forward to watch their seeping and flowing, their spills and jets. (The liquid metaphors are all his.) He is concerned in every examination with the harms blood-languages can inflict. The harms are not random deviations or unexpected deformations. They arise regularly and perhaps necessarily. The “power in the blood” is—like many notions of the divine—both fascinating and dangerous. Languages powerful enough to nurture human lives can also ravage them.

The “power in the blood” is—like many notions of the divine—both fascinating and dangerous. Languages powerful enough to nurture human lives can also ravage them.

Rogers isn’t coy about labeling some applications of blood-language evil (e.g., 166). He offers advice on how to recognize them. But Blood Theology does not intend to provide a complete ethics of blood-languages. It is not a comprehensive history or an encyclopedic survey of their harms. Nor does it gather the dispersed evidence into a single story. (Sometimes it just lists texts or theses. More often, it interrupts itself with excurses.) The book has no section titled “Conclusion.” Instead, the first chapter previews the whole book, and some of its passages (printed in italics) are repeated almost verbatim later on. Rather than building coherence with a cumulative argument or single narrative, Blood Theology binds itself together materially through a net of repetitions. In this and other ways, it mimics the returns of blood-language across times, places, and cultures.

Together, these features turn Blood Theology into something like a notebook. Imagine a colleague handing you a stained lab book. They say: “The topic is too big for completion, but it is also too urgent to wait any longer. This is as far as I’ve gotten.” What we receive in Blood Theology is a compelling interim report backed by samples of evidence. That genre explains the unusual sequence of chapters. The single chapter of part 1, “overtures and refrains,” foretells but does not justify the selection of cases or sites that will follow. Part 2 enters biblical debates over familiar passages about sacrifice, blood-pollution, and Jesus’s last meal with his students. (My description leaves out much, including pictorial censorship of women’s bodies and the relations of menstruation to the very category of “taboo.”) These biblical chapters apply broad theological learning, but they wisely avoid historical synopsis. Part 3 jumps forward before jumping some ways back. Chapters 5 and 6 study blood-language in contemporary US debates about same-sex relations and “creationism.” Chapter 7 returns to early modern debates over “purity of blood” in the Spanish homeland and the (compulsively theologized) conquest of Mexico. In the last section, part 4, one chapter assesses physiological accounts of consuming the Eucharist; the other conducts a christological meditation on recent anthropologies of the agency of things. End of book—except for a substantial appendix that reviews and mostly sets aside a competing account of Christian blood.

The array of topics is overwhelming and lopsided. It must be if it wants to confront the protean powers of Christian blood.

The array of topics is overwhelming and lopsided. It must be if it wants to confront the protean powers of Christian blood. “[This] is a book of bloody fragments. No book about blood could cover everything” (25). Rogers does not try to stitch the fragments into a mock-anatomy. He holds them together by the intensity of his preoccupation. Blood Theology is a notebook but also a journal. Readers who accompany Rogers should learn to see, with him, “patterns that persist, neither apart from history, nor perennially, but across and through their permutations” (27). “Pattern” is sometimes called “shape” but also “tendency” (29, 58). The force underneath the permutations is at once a “Christian theological technology” but also “an anthropological structure” (58). That double description echoes across the book (e.g., 206–7, 214). Rogers refuses to collapse the disciplines or vocabularies that he deploys around blood. He will not declare one analysis or explanation the victor. Perhaps he remembers how blood crosses topics and sciences in its campaigns. Certainly he does not want to confirm Christian theology’s retreat into an alleged sovereignty (187). Queen of the sciences? No. Something more like an alternate and antiquated vocabulary full of risky fantasies.

Blood Theology is enormously inventive in resisting dogmatic simplification. Faced with the juxtaposition of competing disciplines or technical languages, the book’s reader may feel the need for more help with a basic question: What are we pursuing through Christian returns to blood? The question can be taken in several ways. Let me start with the most obvious.

Rogers follows the word “blood” into many Christian contexts where it does not denote blood of any ordinary kind. We are familiar with some of these shifts in daily English. We still hear expressions like “family blood,” “the blood of true Texans,” or “American blood.” These sound physical or biological, but they are of course something else. How to describe their shifts in meaning? And how to connect those shifts with the more varied and potent words about blood among Christians? The “power in the blood” of Jesus underwrites atonement or redemption for all human beings, but it also applies to baptismal cleansing, the renewals of repentance, changes in bread and wine at a eucharistic consecration, or the victories of “spiritual warfare.” Words for that blood reach further into the imagination of cosmology, world history, and fundamental ethics—not to say, denominational identity or polity. Respect for the blood of Jesus is currently invoked to reinforce the subordination of women, to condemn same-sex marriage, and to deny evolution.

What kind of language performs such varied tasks? In Christian thinking, the blood of the Crucified has long been illimitable—in quantity, in pertinence, in supposed power. Rogers recites a short creed:

The blood from the cross is the blood of Christ; the wine of the Eucharist is the blood of Christ; the means of atonement is the blood of Christ; the unity of the church is the blood of Christ; the kinship of believers is the blood of Christ; the cup of salvation is the blood of Christ; icons ooze out the blood of Christ; and the blood of Christ is the blood of God. (14, reprised on 120).

With only a little more elaboration, the blood of Christ becomes the stuff of all creatures. How can language cover so much without becoming gibberish? If it is gibberish, how does it retain so much power?

One explanation for this illimitable language sees it as a set of “social meanings” elaborated around a thing, human blood. Early on, Rogers writes, “blood may be red because iron compounds make it so, but societies draft its material qualities, its color and stickiness, for multiple purposes of their own” (10). To expand: “social blood is more powerful, more real, more substantial than physical blood, because social blood alone conveys meaning” (13). Rogers links social meaning to social structure, then attributes agency or causal power to both structures and societies (“societies draft . . .”). The phrase (or proper name?) “blood of Christ” points to “a large-scale structure that holds together cosmology, fictive kinship, gender roles, ritual practices, atonement for sin, solidarity in suffering, and recruits history and geography to illustrate its purposes” (15, reprised on 120, emphasis added). In other passages, Rogers suggests that social systems make us “so bloody-minded” by loading blood with meanings (19). “If you believe with Durkheim in social agency,” then you are willing to say that “the language of blood recruits” speakers to complete its patterns (150). On these and other pages, it sounds as if “society” empowers blood-language by adding something to it or building something around it—social meanings or social structures. One problem with the explanation is that it is not specific enough. Another is that “social,” like “blood,” starts to appear in many places to perform all sorts of labor.

For someone, like Rogers, who has learned from Wittgenstein that meaning derives from use, all linguistic meaning is social. To name something is already to draft it into group narratives and practices. On this account, no kind of language can have meaning apart from shared use. Medical or scientific terms are freighted with social meaning—not to say driven by historically variable theories. They hardly provide unmediated contact with things. But isn’t there something out there beyond language? Yes. There seem to be a lot of things out there. But as soon as we talk about them, we bring them (or their effigies) in here.

Some accounts of “social” meaning press hard on naming or classification to argue for another level of explanation. Rogers’s pursuit of blood-language sometimes recalls for me Lévi-Strauss’s analysis of myths into combinations of structural units, or mythemes. The combinations were supposed to explain how myths could undergo local variations while retaining cross-cultural similarities. That sounds something like Rogers’s “patterns” in Christian blood-language, but Lévi-Strauss doesn’t appear in Blood Theology. Neither do other studies of mythology, including those that appeal to Jungian archetypes (patterns of another sort). If I’m counting correctly, the word “myth” appears in the book only once. It is applied to the ancient cult of Mithras (63). Rogers doesn’t comment on the term, but he proceeds as if Mithraic stories were different in kind from Israelite and Christian stories. Is that because the latter are true? Or his (ours)? Or still powerful?

When Rogers specifies the social meanings attached to blood, he often turns to notions of symbol or metaphor. For example, he repeats that Christian understandings of eucharistic blood are “metaphorical” (e.g., 12, 39, 57, 60). I understand him to mean that Eucharists are not performed using ordinary human blood. But I don’t see a metaphor. For example, Roman Catholic Eucharists are celebrated with (real) wine. That church’s doctrine holds that the wine and bread are (really) changed into the blood and body of Jesus Christ—even if they never look, smell, or taste like human blood and flesh. Where’s the metaphor? On other Christian doctrines, of course, there is no substantial change, but neither is the wine treated as a metaphor for blood. In some of his discussions, Rogers tries to qualify “metaphor” by adding the adjective “paraphysical.” Certain metaphors are paraphysical or parabiological: “they extend even to the breaking point the metaphors of kinship” by expanding “rigid accounts of God and nature” (111 with 128). But hadn’t ordinary notions of “metaphor” been abandoned long before that breaking point? The unbounded reach of “blood” or “kinship” in Christian theology has been, all along, something stranger than metaphor.

Perhaps we can understand better if we reverse the framing. When is Christian speech about blood not metaphorical? Consider a deliberately naive reading of Leviticus 17, a short text that retains authority for many Christian readers. In chapter 17, God addresses Moses, who is instructed to speak a series of divine commands (verses 1–2). The commands both display and justify God’s concerns for blood. Blood is or carries nephesh (soul, spirit, life . . .). Because of it, blood can cleanse and pollute, atone and condemn (as Rogers repeats). But nephesh is owed to God (and not, say, to demons in the form of goats [verse 7]). Much of the chapter’s language refers to observable actions: sprinkling blood on the altar, slaughtering animals, washing up after eating carrion. Still, these “literal” commands are colored by divine threat and explanation. Anyone who violates the commands reported here will be expelled from the group (verses 4, 9, 10, 14). The punitive commands are explained by pointing to the nephesh that is in blood (verse 11) or simply is blood (verse 14).

So far, my naive, Christian reading of Leviticus 17. Does it make sense to distinguish literal from metaphorical meanings in that reading? Suppose I want to say that the word “blood” is literal when it refers to the fluid sprinkled on the altar but metaphorical when it designates pollution or an animating life owed to God. But the command to sprinkle blood on the altar rests on the explanation that God gave blood with nephesh to humans so that they might return it for atonement (verse 11). Where does metaphorical blood start—or, more exactly, where does it end? Whether it is nowhere or everywhere, metaphor is not a useful category for analyzing Christian discourses about blood. Neither, for similar reasons, is symbol. We need something else.

Metaphor is not a useful category for analyzing Christian discourses about blood. Neither, for similar reasons, is symbol. We need something else.

Rogers tells us that his own title for the book was “the analogy of blood” (20, emphasis added). He explains that “analogy” is how theologians name what anthropologists call “totem.” For the anthropological view, he paraphrases Durkheim: totem identifies a society with its cosmology and its god. “In Christian terms,” not further specified, analogy establishes “a multilevel hierarchy whereby God elevates human beings, gift upon gift, into participation in God’s own life” (13). Anyone familiar with theological controversies about analogy may want to interject, Which version of analogy—or whose analogy?

Sometimes, as in what follows this quotation, Rogers points to Aquinas (14). As a scarred veteran of neo-Thomist controversies over analogy, I’m not sure how much invoking Aquinas explains. (Which Aquinas? Whose Aquinas?) It is more helpful to set Aquinas aside and return to Rogers’s key phrase: “what analogy does . . . [is] establish a multilevel hierarchy whereby God elevates human beings, gift upon gift, into participation in God’s own life” (13). That sounds very much like the prologue to Bonaventure’s short meditation (or notebook), Mind’s Road to God. In a series of dazzling parallels, using relations of trace (vestigium) and image (imago), Bonaventure maps hierarchies of resemblance that can lead the human mind from sensation or knowledge about things to sharing life with the Trinity. Do you hear the resemblance to Rogers: “a multilevel hierarchy,” “gift upon gift,” “participation in God’s own life”? There is something more striking. For Bonaventure, every creaturely hierarchy is the road that leads Jesus to public death. At his meditation’s end, Bonaventure counsels: If you want to ascend all the way, you must enter smoky fire and take lessons from dark light. You must undergo death.—I turn away from the hypnotic beauties of Bonaventure’s prose-poem to repeat my point: Rogers’ description of analogy sounds more like exemplarity or typology than Thomistic analogy.

The reframing matters because exemplarity is better at blurring the boundaries between words and things, grammar and ontology. Rogers likes that blurring. He performs it in his most lyrical passages—especially when he is trying to resist the powers unleashed by blood-languages. Exemplary causality is also more attuned to permutations across time—not outside of history, but across it (just as Rogers says of his patterns). Again, exemplary causality is often said to multiply effects endlessly: so many traces or images of so many kinds. Of course, I concede that my Bonaventurian reading of Rogers has consequences that may be more obnoxious to him than to me.

Exemplarity is not a form of causality congenial to modern sciences—just as typology is not a style of interpretation favored by contemporary exegetes. Indeed, some writers suggest that exemplarity just doesn’t fit within modern frames of experience. (In the theological scripts of Pierre Klossowski, Michel Foucault claims to find a long-lost way of representing human encounters with divinity. Such representations were banished from philosophy and theology with the arrival of modernity.) Rogers does sometimes recall exemplary or typological ways of writing theology. He says, for example, that the notion of the literal works from God down (191) or that “the structure of things is understanding waiting to happen” (208). But his commitment to juxtaposing social sciences with theology minimizes the possibility that some important theological thinking won’t fit inside that grid. What if deep mechanisms for circulating Christian blood-language cannot be rendered within notions of social meaning, metaphor-and-symbol, or (prevailing models of) analogy? What if currently acceptable notions refuse to imagine a bond of creation that enables divine blood to flow through everything? I can paraphrase my questions much more specifically: Rogers cites Maximus the Confessor at crucial moments in Blood Theology. The saintly theologian offers consoling antidotes to the worst toxins in idioms of divine blood. Maximus shows how to speak blood otherwise. But what if the grammar of that old speech vanishes under prevailing models of meaning?

I believe that Rogers sets asides such scruples about representation or translation because his chief aim is not to reproduce the past. He wants rather to alter our present and future. We engage with the power of blood “to change social meanings: not only to revive or resist, but also to vary, divert, re-channel, dissipate, or exhaust them” (13). More precisely: “Having understood Christian blood discourse as an anthropologist, my task now as a theologian is to repair it” (124). The ground for hope in repair is christological: human beings, including theologians, “can participate in God’s repair of blood, because all blood belongs to God, and thus to Christ” (35).—Note again the strong sense of exemplarity.

The almost paralyzing poignancy that Rogers’s hope raises is admitting that you can write ethically urgent theology, put it before competent Christian readers, and then see it ignored or overwritten in the name of Christian solidarity.

I endorse the hopes, but I also notice that they bring forward the almost paralyzing poignancy of theological writing. This poignancy is not, say, a writer’s failure to compose what was planned or imagined. Nor is it a sense of the limits on revivifying old texts. It is not even deeply felt disappointment at writing thoughtful theology only to have it lost in ambient chatter. The almost paralyzing poignancy that Rogers’s hope raises is admitting that you can write ethically urgent theology, put it before competent Christian readers, and then see it ignored or overwritten in the name of Christian solidarity. Rogers describes exactly this poignancy in Spanish campaigns against converts carrying “Jewish” (or, I add, “Muslim”) blood: How did the “untheology” of blood purity overwhelm the “real theology” that opposed it with fundamental teachings on baptism or universal salvation? Why did the real theology fail “so fecklessly,” remaining “of little effect” (164)?

Rogers answers his own questions: “The real theology failed because of sin. It lost not in the intellect but in the heart” (164). I agree, but I hear other questions that follow immediately. Why, then, should we keep writing theology in more or less feckless ways? Why not concentrate our energies instead on acts of bodily care while waiting for God to change hearts? There is a standard answer, which goes back at least to Augustine: We keep writing (or teaching or preaching) because we never know which words might serve an outpouring of God’s grace. The standard answer is at best partial and perhaps too convenient for present arrangements. A fuller answer must lie “not in the intellect but in the heart.”

Theologians continue to write—in forms they’ve learned or invented—because they continue to believe that having the right words will hasten God’s transformation of the world. They—we, I—seek blood-language that might count as “words (rêmata) of eternal life” (John 6:68). Not logoi—speeches, arguments, teachings, rational patterns—but rêmata, spoken words, sayings, or (in grammar) verbs. Words that move, that have spirit in them—as we say. Rogers has spent years on the expert assembly of words that might sway or stay violent uses of blood-language. Having summoned its righteously unforgiving tide, he speaks—in his most lyrical passages—something like a counter-incantation. He queers the language, and then he performs it as an example or exemplar. Whether that response is enough, whether this profoundly theological book remains feckless for a short or long time, is not for him to decide. Readers have a say. So do the powers moving through them. Whatever happens next, Blood Theology is a book that makes writing Christian theology seem again to be worth all effort.

Mark D. Jordan is the Richard Reinhold Niebuhr Research Professor of Divinity at Harvard Divinity School. He is a scholar of Christian theology, European philosophy, and ethics for sexes and genders. His forthcoming book, “Queer Callings: Untimely Notes on Names and Desires,” recalls the spiritual languages lost in a rush to promulgate politically effective identities.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.