Featured

White Hats and Black Hats

A documentary filmmaker searches for humanity behind the symbols.

Cities of Light: The Rise and Fall of Islamic Spain was broadcast nationally on PBS in August 2007.

By Alex Kronemer

Let me tell you a joke. Not just any joke. This is the joke that defines my life. It should probably be carved onto my tombstone when I die. And if it is, my children will have done it out of spite, since they’ve had to sit through a fair number of the thousand times or more that I’ve told it. I include it in almost every speech I give, and, as you can see, in my writing, too.

I love this joke for many reasons, some of them selfish. Hearing it the first time helped propel me into documentary filmmaking, a career I’m very grateful to have. And maybe it will become one of your favorite jokes too, though I give you fair warning: some people don’t like it at all. It does have a certain squirm factor to it.

But that’s part of the main reason that I tell it so often. Not because I like to see people squirm, but because it hits a vein. In my opinion, the vein. To me, this joke does nothing less than address the root cause of the clash of civilizations, the conflict that not only divides us as nations and peoples, but also diminishes our souls and robs us, as individuals, of our good works.

So here it is. I first heard it from a rabbi who was trying to make a point about religious intolerance. The joke takes place in Rome, in the Middle Ages, at a time when the Catholic community and the Jewish community aren’t getting along. The pope calls in the head rabbi and says, “I think it’s best if the Jews would just leave Rome.” The rabbi considers what the pope is saying and comes up with an idea. “Let me make a deal with you,” he says. “Let’s have a theological debate. If I should win, we get to stay. If I should lose, we’ll leave without a fight.”

The pope agrees, but immediately there is a problem. Which theological language, Hebrew or Latin, should the debate be in? They argue for a while, and finally come upon a solution. They agree to have the debate nonverbally, using just hand gestures.

Of course, once the news gets out about the debate, it becomes a very big deal. So many people want to see the debate that a wooden stage is built in St. Peter’s Square.

On the morning of the debate, the pope climbs to the stage from one side and the rabbi from the other. The pope begins. First the pope puts up three fingers. Without a moment’s hesitation, the rabbi puts up one. The pope nods thoughtfully. He ponders a moment, and then raises his hand and makes a sweeping gesture over his head. Again, without a moment’s hesitation, the rabbi points firmly to the ground. Once more, the pope nods thoughtfully. He clearly is impressed. After a few moments of consideration, he turns to a table behind him on which he has placed the communion wafer and wine. He picks them up and holds them in front of the rabbi.

For the first time, the rabbi seems stumped. He ponders for a moment, then shrugs, reaches into his cloak, and pulls out an apple, at which point the pope raises his hands in defeat. “The debate’s over,” he declares. “The rabbi wins. The Jews can stay in Rome!”

Down from the stage he goes. Immediately, he’s mobbed by all the bishops and cardinals who are there. “What was this debate all about?” they ask.

“Oh, it was a fascinating debate,” he says. “First I put up three fingers to signify the Trinity. And the rabbi raised one to remind me that we all share one God in common. So I made a gesture over my head to say that God sits in his majesty in the heavens above. And the rabbi pointed to the ground to remind me that God is on earth watching and judging. So I took out the wine and the bread to signify Redemption. And he took out the apple to remind me of the sin of Adam, which we all share in common.”

Meanwhile, the same conversation was happening with the rabbi and his followers. “What a weird debate,” the rabbi said to his followers. They all nodded in agreement. “First, the pope puts up three fingers, saying that the Jews have to leave Rome in three days. So I put up one to say that not one of us is going to go. That made him mad, so he sweeps his hand over his head saying that the Jews had to leave Rome. I point to the ground, saying we’re staying right where we are. Then he signals that he wants to have a break by taking out his lunch!” The rabbi shrugged. “So, naturally, I take out mine.”

Long before 9/11 and all the events that have followed, this joke gave me a valuable insight. If we take it seriously for a second, something powerful is being said. When the pope puts up his three fingers, they clearly signify to him a beautiful, central theological idea in Christianity. Yet the rabbi has a completely different interpretation. To him they signify something sinister. And what the rabbi sees as merely food—the apple—the pope sees as the symbol for the fall of mankind from Paradise.

What the joke says is that maybe what we face is more a clash of symbols than a clash of civilizations. We misinterpret what each other’s symbols mean—especially sacred symbols. By this, I don’t just mean overtly religious symbols like crucifixes or Stars of David, but also sacred values and concepts, including “secular” ones. And if we ever needed any proof of how a mistaken understanding of symbols can cause an actual clash, all we have to do is go back last year to the Danish cartoon controversy.

What the Danish newspaper editors saw as a symbol of free speech, many Muslims saw as a symbol of hostility and disrespect to Islam. What agitators in Pakistan cited as a symbol of Western hostility to rally deadly protests, many in the West cited as a symbol of Muslim violence and barbarism. All combined, this misinterpretation of symbols further widened the gulf of distrust between the Western and Islamic worlds, provided fodder for warmongers on both sides of the divide, and dispirited those working for peace and reconciliation.

That is why the media plays such a crucial role in how the current clash will ultimately be resolved, and that is why documentaries are so important. The media, and documentary films, are in the symbol business. Symbols are the language of visual communication. In a movie, or a news piece, symbols are used as a necessary shortcut to visual storytelling.

The classic example is the good old-fashioned western. Say the movie opens with a dusty town at high noon. Two gunslingers stand opposite each other, ready to gunfight. One is wearing a white hat, the other a black hat. Without a word of dialogue or back story, we immediately know who the good guy is and who the bad guy is. We know who probably helped an old woman across the street that morning, and who kicked a dog. We know who needlessly provoked the fight, and who is protecting some cherished value. In short, we know who is virtuous and who is evil.

As a storytelling device, symbols like these play a very important role. They help move the action forward to get to the main issue that people care about in all storytelling, which is, “What happens?” But this very valuable tool for visual storytelling can have negative effects, too.

What happens when the black hat gets replaced with a Muslim headscarf, or a yarmulke, or a turban? What happens when the “black hat” is the way a person bows in prayer, or is a certain skin color or a certain kind of accent? What happens when the symbol for a welfare mother is an inner-city black woman (even though the vast majority on welfare are rural and white), or when the symbol for a drug dealer is a person with a Spanish accent, or the terrorist is an Arab? The obvious result is the reinforcement of stereotypes.

The bigger problem is that, like a Frankenstein monster, symbols—especially stereotypical ones—can come to control the story lines they are supposed to serve, so that the only information about a people, a religion, or a place is the prevailing symbol about it. Going back to the example of Pakistan: While the demonstrations against the cartoons were going on, many other newsworthy events were occurring in this diverse, complicated country, whose population is the sixth largest in the world. Yet, the prevailing symbol of Pakistan as the land of fundamentalist mullahs and bearded fanatics barely allows for any other story line to emerge from it—so much so that even Democratic candidate Barak Obama can suggest possibly bombing it. (Not to be outdone, one of the Republican presidential candidates, Tom Tancredo, has reduced the world’s one-billion-plus Muslims to a stereotype by saying that he would bomb Mecca if the United States were attacked again by al-Qaeda or a related group.) Symbols and story lines not only determine how we think about something, but also how we feel about it.

Since as far back as Aristotle’s Poetics, thinkers have tried to understand why enacted stories, such as plays, movies, or, today, the televised news, seem to have such a powerful emotional effect on people. According to research, it turns out that our brains have something called “mirror neurons.” Neurons are the fibers in our brains that fire the electronic charges that stimulate muscle movement. Mirror neurons fire when we watch someone do something, as if we ourselves were doing it. So in the joke, not only would neurons fire in the pope’s brain when he raised three fingers, they would fire in the rabbi’s brain as well, as if he were doing it, too.

A good documentary takes a nice, neat symbol and muddies it up. It does this through the language of film.

The most compelling theory for why we have mirror neurons is that because of our higher intelligence, our social environment is extremely complex. Mirror neurons allow us, literally, to read minds, to be able to grasp instantly that when the pope raises his three fingers, he is making a debating point, not about to poke the rabbi’s eyes. People suffering from autism, for example, appear to have damaged mirror neuron functioning, which helps explain why they have such impaired social functioning.

From the point of view of visual storytelling, this means that in addition to providing information, the visual storytelling format literally provides an experience. Not only does the audience see a symbol, it actually lives it vicariously.

This is why documentary films are so important and this is what got me interested in making them. The primary value of a documentary is to take a symbol and dig deeper, explore its contradictions, uncover the broader story, and debunk the knee-jerk reactions it stimulates. In short, a good documentary takes a nice, neat symbol and muddies it up. It does this through the language of film, which is to say, it does it through the powerful emotional vehicle of visual storytelling. Not only can a documentary bring a better and more comprehensive understanding to the reality behind a symbol, it can also, we hope, engender a more humane attitude about that reality as well.

Even history, the most messy of all things, is often turned into a symbol. For the last two years I’ve helped produce a documentary on Islamic Spain, called Cities of Light: The Rise and Fall of Islamic Spain. What got me interested in the topic were the sharply different interpretations that history symbolized. Before 9/11, I mainly knew the history of Islamic Spain as a symbol for coexistence among the Abrahamic faiths, a golden age when Christians, Muslims, and Jews lived together. I was therefore surprised to learn that for Osama bin Laden, this history was the reason for the attacks because it symbolized the beginning of the long downturn in Islamic civilization, a downturn that he is hoping to reverse through violence.

What was it about this history that could lead to such differing interpretations? As I began to research it, I found a story of great relevance to the challenges we currently face. It was a symbol with a very complex reality that presented both an example of pluralism and a warning about religious violence.

Islamic Spain lasted longer than the Roman Empire. It marked a period and a place where for hundreds of years a relative religious tolerance prevailed in Medieval Europe. At its peak, it lit the Dark Ages with science and philosophy, poetry, art, and architecture. Breakthroughs in medicine, the introduction of the number zero to the European world, the lost philosophy of Aristotle, even the prototype for the guitar, all came to Europe through Islamic Spain. Not until the Renaissance was so much culture produced in the West.

Its successes came from its pluralism. When the first Muslims crossed the Strait of Gibraltar into Spain, the large Jewish population there was enduring a period of oppression by the Catholic Visigoths, who had recently emerged from their own religious civil war. The Jewish minorities rallied to aid the Arab Muslims as liberators, and the divided Visigoths fell.

The conquering Arab Muslims remained a minority for many years, but they were able to govern their Catholic and Jewish citizens by a policy of inclusiveness. Even as Islam slowly grew over the centuries to be the majority religion in Spain, this spirit was largely, if not always perfectly, maintained.

Pluralistic though it was, Islamic Spain was no democracy. After years of enlightened leadership, a succession of bad leaders caused the unified Muslim kingdom to fragment among many smaller petty kingdoms and fiefdoms. Although these smaller kingdoms competed and fought, the spirit of pluralism continued. Indeed, it thrived as rival kings sought the best minds in the Muslim, Christian, and Jewish worlds for their courts. This was just as true in the Christian petty kingdoms as the Muslim ones. It was a complex society and people behaved in a complex way. Christian and Muslim armies even fought alongside each other against mutual rivals of both faiths.

But as the ongoing competition for land, resources, and power endured, some leaders on both sides began to appeal to religion to rally support for their cause. This required persuasion and storytelling with “white hats” and “black hats.” Increasingly, the complexity of relations began to give way as people began to reduce each other to symbols and slogans. What had been a relatively minor tendency toward religious extremism in the Christian and Muslim Spanish world was more and more often nourished and supported for political gain. Increasingly, wars were religious in nature, with Christians fighting Muslims because they were Muslim, and Muslims fighting Christians because they were Christian. Once let out of the bottle, the genie of religious violence proved impossible to put back in.

Into this tinderbox, a match was thrown. It started as an idealistic mission by the Christian West to liberate part of the Middle East from an oppressive leader who also threatened Western interests. But the cause eventually descended into barbarism and protracted warfare. We know it as the Crusades—the same term that many Arabs use today when referring to United States involvement in Iraq.

Then, as today, that conflict colored everything and further deepened the divide among the religions in Spain. Minorities in both Christian and Muslim kingdoms became increasingly suspect. Persecution, expulsions, and further warfare ensued. Nothing could stop it, not even the Black Plague, which only created a temporary hiatus.

Ultimately, Christian kingdoms gained the upper hand as, one by one, the Muslim kingdoms of Islamic Spain fell (this is the period that Osama bin Laden cites in his agitation propaganda). With the defeat of the last Muslim kingdom, Spain’s Muslims and Jews were forced either to leave or to convert. Many were expelled, while many others converted, at least outwardly. This eventually became one of the main preoccupations of the Inquisition, whose purpose was to verify the loyalty of those suspect converts.

The story of religious violence, especially in Europe, goes on and on from there, down through the centuries. Only in recent times has a relative inter- and intrareligious rapprochement been seen, and that may prove to be a brief interregnum if some of the angry men of the Abrahamic faiths get their way and reduce their opponents to symbols of evil.

So far, the post-9/11 world and the events it has spawned seem to be heading in the same dangerous direction as witnessed before. Like a re-emergent virus, the religious intolerance that engulfed and overwhelmed Medieval Spain threatens the increasingly beleaguered pluralism of our own time.

As I’ve said, the job of a documentary is to try to remind people of the complexity of the experience behind a symbol. Being a Harvard Divinity School graduate, I want to also add this: If documentary films are required for this job, it is because mainstream religion has increasingly not been doing its job. The same impulse of documentary filmmaking for humanizing a symbol is at the heart of the monotheistic faiths. Judaism, Christianity, and Islam are all based on a collection of narrative stories. There is an essential complexity in the monotheistic vision that should work against simpleminded symbol making.

The Hebrew scriptures are not only the Ten Commandments, but are also the stories of Adam and Noah, Abraham, David, and Moses—complicated people who don’t always live up to those principles. The Gospel is not just an explication on the idea of redemption, but is also the story of the struggles and failures of discipleship. The Qur’an is not only Islamic law, but is also an extended narrative on the difficulty of living up to that law and God’s ultimate mercy to those who try.

In short, there is a humaneness at the heart of monotheism, a spirit of tolerance that comes from the contemplation of human imperfection. More than absolute principles, the stories of the shortcomings of people trying to live up to them are the foundational ideas upon which monotheism stands. To be sure, there are “bad guys” and “good guys” in the biblical and Qur’anic stories, but not very often “white hats” and “black hats.” Even in the Christian story of the crucifixion of Jesus, a Roman soldier has a change of heart, while Peter is temporarily losing heart. But the prevailing narrative among the religions for the last several hundred years has too often been one of “white hats” and “black hats,” witnessed in countless pogroms of Jews that would follow Easter Sunday services.

The tragic reality that underlies the joke of the pope and the rabbi is that theological debates were frequently staged in Medieval Spain, pitting Jews in a no-win situation against Catholics. Lose the debate, and they lost; win the debate, and the debating Jew might be killed by a mob or exiled as a heretic.

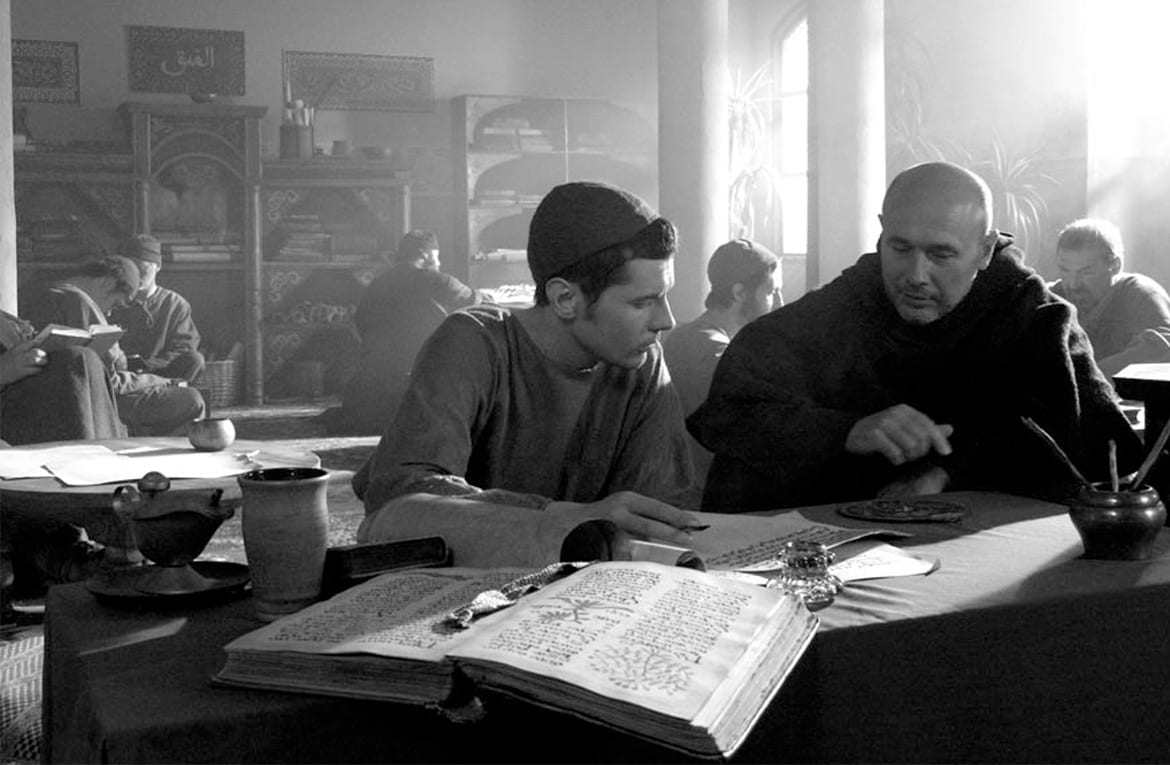

But Medieval Spain also offers another vision. In the pluralistic years, Jews, Muslims, and Christians often worked together to translate into Latin and expand on the writings of the ancient Greeks, which then existed mainly in Arabic. These works spread across Europe and helped lay the foundation for the Renaissance. In one of the scenes from the film, a Muslim, a Catholic, and a Jewish translator reach across the tome they are working on together to touch each other in a gesture of fraternity and mutual respect.

If Cities of Light succeeds, it will be in telling a history that is both a model and a warning. It can inspire interfaith cooperation among those who seek an easier relationship among the three Abrahamic faiths. It can also serve as a warning of what can and has occurred when political and religious leaders divide the world into faith camps and work to isolate the other. It reminds us of the disastrous results when symbols, and civilizations, clash.

Alex Kronemer, MTS ’85, is the co-founder of the Unity Productions Foundation, creator and producer of the 2002 PBS documentary Muhammad: Legacy of a Prophet, and executive producer of Cities of Light: The Rise and Fall of Islamic Spain and Prince Among Slaves, which tells the true story of an African prince enslaved 40 years in Mississippi. More information on his company and productions can be found at www.upf.tv.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.