Featured

Understanding White Evangelical Views on Immigration

For this cultural group, militant masculinity trumps the Bible.

By Kristin Kobes Du Mez

What factors shape how white evangelicals approach the question of immigration? On the one hand, the Bible, and Christian tradition, have a lot to say about loving the stranger and caring for the foreigner. There is a universality within the Christian faith that ostensibly cuts across tribe and nation. Indeed, a strong Christian case can be made for extending a “radical hospitality,” for permeable borders, and for a compassionate approach to immigration.

And yet, white evangelicals—those who claim to hold the Bible in highest regard—are more opposed to immigration reform, and have more negative views about immigrants, than any other religious demographic.1 This, despite the advocacy efforts of many evangelical organizations and prominent leaders.

In fact, the Bible appears to hold little sway when it comes to immigration: a 2015 LifeWay Research poll found that 90 percent of all evangelicals say that “the Scripture has no impact on their views toward immigration reform.”2 Evangelicals, then, are not basing their views on scripture. Instead, they are acting out of a powerful, cohesive worldview—an ideology that is at the heart of their religious and political identity, an ideology influenced by conservative media sources but that is also deeply rooted in their own faith tradition.

Evangelicals I know don’t actually talk all that much about immigration. But they talk a lot about other things, and I want to suggest that these other things position them in critical ways when it comes to views on immigrants, borders, and the American nation.

My own research on masculinity focuses on just one facet of the evangelical worldview—but a foundational one. In many ways, gender provides the glue that holds together their larger ideological framework. For years I’ve been tracing evangelicals’ embrace of increasingly militaristic constructions of masculinity, which go hand in hand with visions of the nation as vulnerable and in need of defense.

To understand contemporary evangelical masculinity, we must look to the past. The 1950s, it turns out, was a critical decade that set the stage for a new understanding of Christian manhood. It was in the early years of the Cold War that gender became closely linked to the security of the American nation. Communists threatened the nation, and the family. They were anti-God, anti-American, and antifamily. Reinforcing proper gender roles—that of male breadwinner/protector and female homemaker/protected—was deemed essential for the security of the American nation.

Evangelicals embraced and promoted Cold War politics. Men like Billy James Hargis and Billy Graham helped awaken Americans to the dangers of communism. They presented a world of stark contrasts, of good versus evil. And America was clearly on the side of the good.

But evangelicals weren’t alone in embracing this Cold War ideology. This was a time of “Cold War consensus,” when liberals and conservatives, Democrats and Republicans, largely agreed when it came to the communist threat. This was the height of American civil religion. God was “on our side.”

In the 1960s, however, this consensus started to unravel—thanks to the civil rights movement, the rise of feminism, and the Vietnam War. Many Americans began to embrace a more critical view of the nation and the military, and they began to abandon “traditional” gender roles. Evangelicals, however, clung tightly to these values. They promoted traditional gender roles, Christian nationalism, and the military. This constellation of issues became central to their religious and political identity and key to their political mobilization in the 1970s.

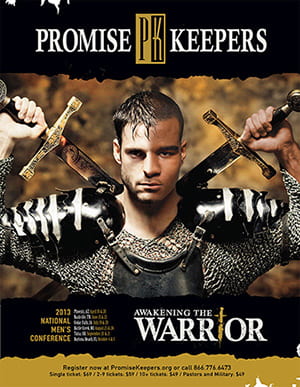

2013 Promise Keepers “Awakening the Warrior” national men’s conference poster.

At the heart of all of this is a militaristic idea of Christian manhood. Figures like James Dobson, Jerry Falwell, Phyllis Schlafly, and Edwin Louis Cole all identified a crisis of masculinity in the 1970s, against the backdrop of the Vietnam War. By 1980, Dobson was blaming feminists for tampering with the “time-honored roles of protector and protected” and for denigrating masculine leadership as “macho.” He saw this as a crisis of gender, but also as a threat to national security. For the sake of the nation, a “call to arms” was needed, a reassertion of the “Judeo-Christian concept of masculinity” in the face of feminists’ “concerted attack on ‘maleness.’ ”3

By the 1980s, evangelical masculinity had become thoroughly imbued with militarism. In the 1990s, with the end of the Cold War and the rise of Promise Keepers, the evangelical organization for men, this militant masculinity softened into the “Tender Warrior” motif. But by the end of the decade, a renewed “crisis of masculinity was identified,” and the time had come to drop the tender and embrace the warrior.

By 2001, books like Dobson’s Bringing Up Boys decried how “a small but noisy band of feminists” has left men “feminized, emasculated, and wimpified.” Douglas Wilson’s Future Men urged that boys be raised to be warriors, to embrace dominion. Most significantly, John Eldredge’s wildly popular Wild at Heart: Discovering the Secret of a Man’s Soul insisted that masculinity was thoroughly militaristic. A “crisis in masculinity” pervaded both church and society because a “warrior culture” no longer existed. Man was made to image God, a warrior God; aggression was “part of the masculine design.”

Only months after Wild at Heart debuted, terrorists struck the United States. Almost overnight, Eldredge’s call for “manly” heroes developed a deep and widespread cultural resonance. Evangelicals, many of whom had never strayed from Cold War gender constructions, stood at the ready to address these new conditions. For them, it was an almost effortless switch from a communist to an Islamic threat: “[W]hen those two planes hit the Twin Towers on September 11, what we suddenly needed were masculine men. Feminized men don’t walk into burning buildings. But masculine men do. That’s why God created men to be masculine.”4

Dobson, too, connected the dots, characterizing “Islamic fundamentalism” as one of the most serious threats to American families: “the security of our homeland and the welfare of our children are, after all, ‘family values.’ ”5 Books on evangelical masculinity sold in the millions. Read as devotionals, studied in small groups, and preached from pulpits, they were consumed as God’s word.

How, precisely, does this militarized evangelical masculinity affect immigration?

It’s important to keep in mind that religion, though often unacknowledged, . . . is deeply embedded in how Americans imagine the border.6 From the Cold War to the present, evangelicals have perceived the American nation as vulnerable. Strong, aggressive, militant men must defend “her.” The border is this line of defense. Many evangelicals see the border as a site of danger rather than as a place of exchange or a site of hospitality.

Presently, the key threat evangelicals perceive is the threat of terrorism, and, in the minds of evangelicals and despite much evidence to the contrary, immigrants and refugees are linked to terrorism. Immigration activists working in faith communities have noted an increase in this tendency following the election of Trump. Those working in refugee resettlement have found that, when speaking with evangelicals, they must give much more attention to the finer points of how refugees are screened and vetted before being allowed into the United States.

It is also important to note that, for white evangelicals, this aggressive, militant masculinity is a racialized masculinity. Black men, Middle Eastern men, Hispanic men are not called to a wild, militant masculinity. Their aggression is dangerous, a threat to the stability of home and nation.

Since the 1960s, we also see a dogged commitment to “law and order” among white evangelicals. What started as a backlash against hippies, civil rights activists, and Vietnam-era antiwar protestors, has led to an idealization of law enforcement and the military; border control agents fall into this category as well.

In light of ongoing and ever-present threats, many evangelicals have concluded that we need strong men, and a strongman. For this reason, President Trump’s “character flaws” aren’t the stumbling block we might expect them to be. In the words of Rev. Robert Jeffress: “I want the meanest, toughest, son-of-a-you-know-what I can find in that role, and I think that’s where many evangelicals are.”7

Evangelicals like to claim that the Bible is central to their identities and to their social and political commitments, and many scholars continue to define evangelicals in terms of their doctrinal commitments. But this misses the bigger picture. Evangelicalism is a historical and cultural movement.

For activists who want to change evangelical views on immigration, quoting scripture will not have much impact unless they find ways to disrupt this larger constellation of commitments.

How, then, might religious literacy help us speak across this divide?

In limited ways, it can help to speak the language of evangelicals. Tapping into evangelical support for “family values,” for example, one might emphasize the importance of keeping families together. This approach, however, is limited in light of the recent conservative demonization of “chain migration,” which has effectively framed family reunification as a threat rather than a good.

Sharing individual stories can also help reveal the human dimensions of failed immigration policies. However, evangelicals have always exhibited a strong streak of individualism and often see individual cases as just that, without looking to the larger systems that dictate the terms of those stories. In this way, white evangelical Iowa farmers may care about their undocumented laborers in a personal way, yet still place a large “Re-elect Steve King” sign in their front yard. Or they may consider someone they know personally as one of “the good ones,” someone “not like the other ones.” In this way, there can be a sizable disconnect between personal sentiments and views on immigration policy.

In a similar fashion, speaking the language of “innocent” victims, of people who have ended up in circumstances through no fault of their own, can also connect with evangelicals. But this, too, can be a short-sighted approach. For instance, emphasizing the “innocence” of Dreamers may have the inadvertent effect of throwing their parents under the proverbial bus, a tradeoff many Dreamers themselves are unwilling to make. More importantly, the language of “innocence” ends up propping up simplistic and perhaps unjust notions of “law and order,” while obscuring the larger structural issues that must be confronted if we are to address questions of justice on a national and a global scale. When it comes to distinguishing the “deserving” from those “undeserving” of assistance, the line is frequently drawn in a narrow, legalistic way; for those who “broke the law,” mercy is inappropriate.8

Rather than attempting to devise tactics to appeal to evangelicals in the current climate, the bigger, more important question that must be addressed is how religious literacy might help us reshape contingent cultural norms to more effectively pursue peace and justice.9 How, in other words, can we speak in ways that address evangelicals’ underlying ideological commitments?

In this regard, it’s hard to be optimistic. It is incredibly difficult to disrupt a cohesive worldview of this sort, particularly one that is inherently suspicious of opposing views and is fueled by a victimization narrative, one backed by a multi-billion-dollar spiritual-industrial complex, and one that has direct and exclusive avenues of communication to hundreds of millions of eager consumers.

In addition to crucial on-the-ground, issue-based advocacy, it would be prudent to invest in faith-based public scholarship and popular literature that works to disrupt reigning ideologies within religious communities. The resources of the religious left (and center) have always been dwarfed by the money pouring into the Religious Right. It will take a concerted effort to offer competing narratives that might open communities of faith up to rethinking immigration in light of the biblical call to welcome the stranger and to love one’s neighbor as oneself.

Notes:

- Betsy Cooper et al., “How Americans View Immigrants, and What They Want from Immigration Reform: Findings from the 2015 American Values Atlas,” Public Religion Research Institute.

- Evangelical Views on Immigration, Sponsored by the Evangelical Immigration Table and World Relief, February 2015 (PDF).

- See James Dobson, Straight Talk to Men and Their Wives (Word Books, 1980).

- Steve Farrar, King Me: What Every Son Wants and Needs from His Father (Moody Publishers, 2005), 120.

- James Dobson, “Family in Crisis,” accessed July 12, 2007.

- “Case Study / Arizona-Mexico Border,” Symposium on Religious Literacy and Government (Religious Literacy and the Professions Initiative, 2017), 1.

- “ ‘Evangelical Elite’ Just Doesn’t Get It, Claims Pastor and Trump Supporter,” Baptist News Global, March 16, 2016.

- I am grateful to Kate Kooyman and Kris Van Engen of the Christian Reformed Church’s Office of Social Justice for sharing their insights on outreach to faith communities.

- This is one of several thought-provoking questions raised in the RLP’s “Case Study / Arizona-Mexico Border.”

Kristin Kobes Du Mez is Professor of History at Calvin College. The author of A New Gospel for Women (Oxford, 2015), she is currently writing a book on evangelical masculinity, militarism, and the rise of Donald Trump.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.

I think that your conclusions come from presuppositions about White Evangelicals that seem to be supported by polling data and reinforced by scholars with a predisposition toward feminism and post-modern views on government, family, and the church. It might appear that Dobson and Wilson are leading the charge for masculinity, but more likely they are responding to the three waves of feminism and its influence on society and the church. No where is this more apparent than your connection between Wild at Heart and 9/11. The one did not really influence the other. Rather, as the data determines (and you tacitly admit in the following paragraph), the book simply resonated with people who already thought the same way.

It’s a bit disconcerting that such feminism is alive and well at Calvin College. I’m not surprised, since the school is only borderline evangelical anyway having given up on the core doctrines of the faith long ago. It’s still sad.