Featured

Not All Rosy: Religion and Refugee Resettlement in the U.S.

Resettling refugees has always evinced both tension and generosity.

South Vietnamese refugees arrive on a U.S. Navy vessel during Operation Frequent Wind, 1975. Wikimedia Commons, CC-PD

By Melissa Borja

In the past three years, one of the largest refugee crises in human history has unfolded, and along with it has come an outburst of anti-refugee hostility. In the United States, where political leaders have associated refugees with terrorism, opposition to refugees is widespread and at times vicious, as shown in the October 2017 events in Shelbyville, Tennessee. There, the anti-refugee and anti-Muslim activism in Shelbyville provoked its own backlash and drew a strong rebuke from Americans who take pride in the idea that the United States is a refuge for the persecuted and a haven for people of all religions. History offers an important corrective to that rosy exceptionalist narrative, though. The truth is that refugee resettlement has always been contentious in the United States, and the anti-refugee hostility on display in Shelbyville is hardly a new development. Even at times when public and private responses to refugees have been the most generous, American refugee care has always been complicated and controversial, especially on matters of religious and racial difference.

A look to the past—specifically, to Southeast Asian refugee resettlement four decades ago—offers useful insights into current debates about refugee resettlement and religious life today. Amid the fallout of the Vietnam War, the United States undertook an expansive, decades-long effort to resettle over one million refugees from Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos. These refugees marked a turning point in the history of American refugee care. Along with the Ugandan Asian refugees who arrived two years before them, Southeast Asian refugees were nonwhite, non-European, and predominantly non-Christian, and they introduced a new religious pluralism to the American system of refugee care. Historically, the private voluntary agencies that perform most of the on-the-ground labor of refugee care have been Christian organizations that, until the 1970s, resettled people of their own faith tradition. Southeast Asian refugees forced these agencies to recalibrate their policies and practices and adapt to a new multireligious clientele. The challenges that faced Americans then resonate with the challenges that face us today, and we can learn valuable lessons from that past resettlement effort.

Lesson #1: Anti-refugee sentiment is long-standing and common.

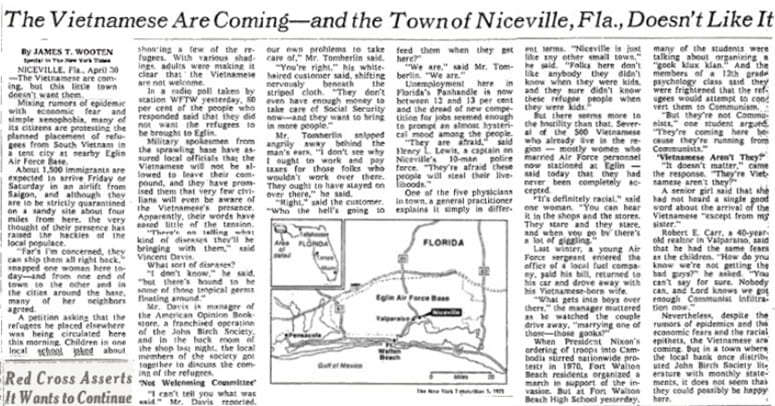

In 1975, The New York Times covered refugee resettlement efforts in a small Florida town where 1,500 Vietnamese refugees had been placed. The town was named Niceville, but the welcome that residents gave to Southeast Asian newcomers was not especially nice. According to one local radio poll, 80 percent of the town’s residents said that they did not want any more Southeast Asian refugees resettled in their town. Residents cited a number of reasons for their opposition. They expressed concern that refugees would bring diseases and “Communist infiltration.” There were also economic anxieties. “We got enough of our own problems to take care of,” declared one resident, at which point another resident agreed and added: “They don’t even have enough money to take care of Social Security now—and they want to bring in more people.” The article made clear that Niceville residents were not only concerned about the arrival of Vietnamese refugees but were downright hostile to them, exemplified in efforts of local high school students to organize a “gook klux klan.”1

The targets of this antagonism were Vietnamese refugees, not Somali Muslim refugees, but the common themes are clear. The residents of Niceville expressed similar concerns to those of the residents of Shelbyville—in particular, economic competition, national security, and cultural and religious difference—and also revealed an unabashed racism. Moreover, this hostility is consistent with other responses to refugee resettlement projects in American history. Public opinion polls indicate that Americans have almost always been opposed to refugees, and they might even be more supportive now than during past waves. For example, in May 1975, one national public opinion poll from Gallup found that only 36 percent of Americans said that the United States should resettle Vietnamese refugees; 54 percent said it should not.2 Public opinion about Jewish refugees is similar: in January 1939, only 30 percent said that the United States should resettle Jewish refugees; 61 percent said it should not. Public opinion about Syrian refugees is roughly the same: in October 2016, only 41 percent of registered American voters said that the United States should accept Syrian refugees, while 54 percent said it should not. In all cases, a majority of Americans said we should not accept refugees; only about one-third said we should.3

Anti-refugee sentiment appeared to diminish when people in host communities had a clearer understanding of the circumstances that brought refugees to the United States. For example, when Americans knew that Hmong refugees were in the United States because of their partnership with the U.S. military in the fight against communism, or when Americans had a better understanding of the experiences of trauma that refugees had experienced, they were more welcoming.

However, this hostility also became more powerful when directed against religious and ethno-racial minorities, who are seen as particularly threatening and non-American. The hostility against Muslim Somali refugees is in many ways particular to the era of the War on Terror, but it also has much in common with how race and religion intersected in the treatment of Jewish and Southeast Asian refugees during the twentieth century.

1975 New York Times article

Lesson #2: If religion was a source of tension, it was also a source of generosity. Refugee resettlement has long been a public-private, church-state endeavor, and religious institutions have been central to the administrative apparatus of American refugee care.

Scholars of American political development have observed that the United States frequently delegates work to private institutions. Refugee resettlement is an example of this style of “public-private governance.” However, refugee resettlement is unique in that those private institutions are predominantly religious institutions.

Religious institutions have been central to refugee resettlement since before the Second World War. Religious voluntary agencies, church-affiliated charities, and congregations have worked with the government to support refugee relief and resettlement at all levels—internationally, nationally, at the state level, and locally. They have not only aided refugees in the immediate period after resettlement, but they have also been critical to facilitating refugees’ long-term integration, years after their initial arrival.

The government’s reliance on religious institutions has myriad advantages. For one, this system offers social and cultural benefits. Congregations that sponsor refugees and run outreach ministries can offer a network of caring support for refugees. As is clear in the events at Shelbyville, religious groups can also serve as a bridge between refugee and non-refugee communities and help to broker more peaceful relations when tensions arise.

The involvement of religious organizations also allows the government to expand capacity, provide resettlement and relief to a greater number of refugees, and reduce the public cost of refugee resettlement. In 1975, Bethlehem Lutheran Church in Minneapolis found that it cost $5,601 to resettle one Vietnamese refugee family, a cost that eclipsed the $500 per capita grant offered by the federal government.4 This imbalance continues into the present. Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Service (LIRS) conducted a study in 2008 that found that the State Department funded only 39 percent of the actual cost of resettling a refugee, while private giving covered the remaining 61 percent.5 This study revived the long-standing concern that the government consistently underfunds the refugee program and shifts most of the cost unfairly to private (especially religious) groups. Whether or not the current system is fair, the point is still clear: American refugee care runs on the labor and resources of religious groups.

Lesson #3: Delegating work to religious institutions comes at a cost.

Importantly, voluntary agencies like LIRS and congregations like Bethlehem Lutheran are not simply another type of private institution on which the government relies. They are first and foremost religious institutions, with overlapping but nevertheless distinct goals from government. And while these religious institutions have offered undeniable assets—for example, well-established networks of eager volunteers—they have also introduced some important complications.

One issue is that religious organizations are operating in a changing context. Historically, religious voluntary agencies resettled members of their own religious or national community: Catholics resettled fellow Catholics, for example, and Lutherans resettled fellow Lutherans. However, beginning in the 1970s, the predominantly Christian voluntary agencies that had contracts with the federal government to do refugee resettlement began to serve new religious groups—at first, a small group of Ugandan Asian refugees, who were Muslim and Hindu, and then later, a huge wave of refugees from Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos, who were Catholic, Buddhist, animist, and ancestor worshipping. Christian voluntary agencies and churches have adapted to these new circumstances in different ways, to varying degrees. However, they have not always been effective or consistent in their efforts to resettle refugees in accordance with their own stated commitment to accommodate religious difference.

Indeed, questions of religious freedom and religious pluralism in the American system of church-state refugee care remain crucial and, unfortunately, relatively understudied. In general, much of the conversation about government collaboration with faith-based organizations tends to focus on the religious freedom of service providers and the question of whether or not the rights of Christians are imperiled. What has received less attention is the religious freedom of service recipients and, in particular, service recipients who are religious minorities. What do these arrangements look like from the vantage point of non-Christian refugees? Do they see their freedom compromised?

A look at past efforts to resettle Southeast Asian refugees offers insight into these important questions. In general, Christian agencies and churches that resettled Southeast Asian refugees sincerely strived to serve refugees in a way that respected religious difference. There were some genuine efforts to accommodate religious difference. All of the voluntary agencies, for example, created elaborate guides offering recommendations for church sponsors about how to understand and respect the religions of the refugees. Catholic and Lutheran voluntary agencies even made efforts to help Buddhist refugees find monks and temples, out of the belief that supporting refugees in practicing their religious traditions was essential to the long-term success of the resettlement process.

However, accountability was difficult to ensure, given the complex structure of refugee care. Resettlement involved a variety of public and private institutions, connected in a long chain of delegation. In this system, there was a big gap between the professionalized voluntary agency employees who practiced refugee care in a largely secular way and local church volunteers who viewed refugee care as a religious ministry that did not have anything to do with government. It was often these local church volunteers who had the most interaction with refugees. At the same time, these volunteers were not always the most experienced, skilled, or knowledgeable about how to practice pluralism in a meaningful way. Refugee resettlement was sometimes a church volunteer’s first chance to have a close relationship with a non-Christian person.

In these circumstances, church volunteers sometimes made unfortunate missteps. When church groups resettled Ugandan Asian refugees, for example, a strictly vegetarian Brahmin man was given work in a poultry processing plant, which produced psychological and emotional strain. Church volunteers brought Muslim refugees to the mosque—but did so on Sundays, rather than Fridays. While church volunteers by all accounts had good intentions, they struggled to accommodate refugees’ religious differences, in part because they lacked reliable information about the groups that they were aiding. For example, one of the most widely circulated resettlement manuals that voluntary agencies gave to church sponsors drew heavily from a dissertation written by a 1950s Christian missionary, who portrayed indigenous Hmong religion as primitive demon-worship.

Finally, on occasion, church volunteers considered refugee care to be an opportunity to evangelize. Because many of them were already engaged in international affairs and humanitarian work, missionaries were often the people who were most interested in getting involved in refugee care. But along with enthusiasm and global experience, they also brought clearly missionary purposes. In the context of these missionary goals and also the dependent relationship of refugee sponsorship, refugees sometimes reported frustrating experiences of religious pressure. Hmong refugees shared stories of how church sponsors would show up at their door on Sunday and bring them to church, sometimes against their will.

Lesson #4: Delegating work to religious groups raises big issues that are rooted in a very basic question: What is religion?

First, there is the matter of what is religious in public-private refugee work. In trying to ensure that refugees do not experience religious coercion, voluntary agencies tried to manage the religiousness of refugee work and make a distinction between the nonreligious work of resettlement and the religious work of the church. Much depended on one’s interpretation, though. For example, some resettlement manuals encouraged sponsors to bring refugees to Sunday services, in order to allow refugees to develop a network of friends and to experience the hospitality of the church community. Voluntary agencies and church sponsors, therefore, did not consider bringing refugees to church to be an inappropriate religious activity because doing so had a nonreligious objective. However, many refugees did see being brought to worship services on Sunday as a religious act, and sometimes a coercive one. More fundamentally, the distinction between religious and nonreligious work was an artificial one that did not always make sense to church volunteers, many of whom approached refugee care as a ministry animated by deep religious conviction.

Second, there is the question of what gets to count as religion in the lives of refugees. Some aspects of religious life are not immediately legible as “religion,” especially when groups adhere to traditions that are not familiar and recognizable to Christian service providers. Somali refugees who are Muslims have a religion that church sponsors immediately recognize as a legitimate, rightful religion, but others, like the Yazidi people or the Hmong people do not. What about those refugees? How can people respect refugees’ religions if they do not see refugees’ beliefs and practices as “religion” in the first place? There are important consequences of forcing refugees to engage with Americans through a common universal category that is called “religion”—a category that is rooted in the Christian West and that refugees might not necessarily use to describe themselves, at least until they arrive in the United States.

In 1976, Congress passed a law that prohibited the U.S. Census from asking Americans to identify their religion. However, that same year, the United States was directly asking Southeast Asian refugees to identify their religion when they applied for resettlement. This question was a tricky one for Hmong refugees to answer. The government form had check boxes, and they could select only one of several options: Catholic, Protestant, Jewish, Muslim, Buddhist, animist, or ancestor worshippers. The truth is that Hmong people could select multiple categories. They could not even fill out the form properly because the assumptions embedded in the form completely lacked literacy of the religious lives of Hmong people. For a short period of time, the government did away with the check-box question and allowed a free response, and Hmong people simply answered the religious identification question with two words: “Hmong religion.”

When the United States resettles refugees, people in both government and religious institutions need to ask themselves: Are we forcing refugees into boxes that do not make sense? Are we understanding refugees on their terms, or ours? And to what degree do our flawed assumptions and our misapprehensions of other people undermine our shared objectives of integration, inclusion, and freedom?

Notes:

- James T. Wooten, “The Vietnamese Are Corning and the Town of Niceville, Fla., Doesn’t Like It,” The New York Times, May 1, 1975.

- Douglas E. Kneeland, “Wide Hostility Found to Vietnamese Influx,” New York Times, May 2, 1975. A June 1975 Harris poll found slightly more generous numbers—37 percent supported resettlement of Vietnamese refugees, while only 49 percent opposed. Another poll, August 1977, found the split at 31 percent-57 percent.

- Clare Boothe Luce, “Refugees and Guilt,” The New York Times, May 11, 1975; Ishaan Tharoor, “What Americans Thought of Jewish Refugees on the Eve of World War II,” The Washington Post, November 17, 2015; Jens Manuel Krogstad and Jynnah Radford, “Key Facts about Refugees to the U.S.,” Fact Tank, Pew Research Center, January 30, 2017.

- 94th Congress, 1st and 2nd Session on Legislative and Oversight Hearings Regarding Indochina Refugees, “Refugees from Indochina, Hearings Before the Subcommittee on Immigration, Citizenship, and International Law of the Committee on the Judiciary, House of Representatives,” 325–28. The fact that the actual cost of sponsoring refugees was much larger than the per capita grant was well-documented.

- LIRS, The Real Cost of Welcome: A Financial Analysis of Local Refugee Reception (Lutheran Immigrant and Refugee Service, 2011).

Melissa Borja is an assistant professor in the Department of American Culture at the University of Michigan. She is currently writing a book about the impact of U.S. refugee policies on Hmong religious life.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.