In Review

Three Films Depict Sinhalese Buddhism

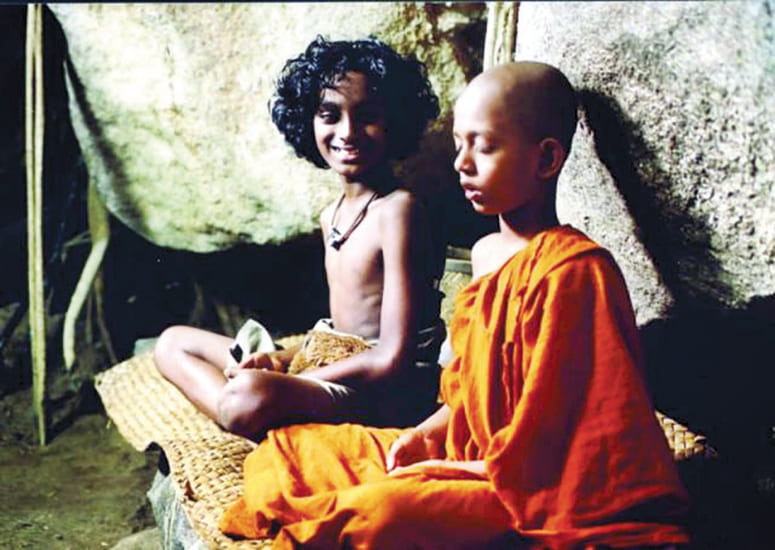

Sankārā depicts the inner struggle of a young monk. Cine Films

By Chipamong Chowdhury

Since 2000, a group of enthusiastic independent filmmakers have created cinematic works of art that have transformed Buddhism in Sri Lanka, where it is largely practiced by the Sinhalese majority. Buddhism is a significant part of the dialogue in such important Sinhalese films as Sūriya Araṇa (2004), Sankārā (2006), and Uppalavannā (2007), among others. These films not only provide us with a visual experience of Buddhism, monastic aestheticism, and contemporary Sinhala Buddhist religious culture, but they also explore fascinating issues and raise urgent questions. In these three Sinhala Buddhist movies, Theravada religion and culture are vividly narrated, interpreted, and reimagined through moving tales that often feature monks or nuns as protagonists. In particular, themes of desire, love, and femininity are exemplified. Through strong storylines, performances, and imagery, these movies portray Buddhist religious characters, beliefs, images, rites, prayers, and material objects. While vividly representing the lives of Theravada Buddhist monks and nuns—including their spiritual crises and social narratives—these films also compel discussions about the limitations of liberalization, especially vis-à-vis the appropriation and commercialization of Buddhism. In cinema and popular culture, what role should Buddhism play? What kinds of stories can be authentically Buddhist and what kinds shouldn’t be?

Prior to the release of Sūriya Araṇa, Sankārā, and Uppalavannā, monastic asceticism was a rare theme in Sinhala Buddhist cinema, but it is a common thread in these three films. These movies are essentially associated with monastic discourses—practices, images, ideals, symbols, and cultures—and with the lives of Buddhist monks and nuns. But what roles do these films play in regenerating, appropriating, and reviving Buddhism in contemporary Sri Lanka? What religious messages do these movies send to Sinhala society in Sri Lanka, and to the Sri Lankan diaspora in the West?

The concept of “Theravada cinema” is a capacious one, covering a wide range of films dealing with the lives of monks and nuns in monasteries, and with the lay Buddhist population—films that reflect Theravada values, cultures, belief systems, and history. Theravada Buddhism is the predominant religion in Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, and Cambodia.1 There are also significant groups practicing Theravada Buddhism in Bangladesh and Nepal. Despite cultural, geographic, national, and linguistic differences, what unites all of these diverse Theravada cultures is the Theravada identity and Theravada values, which are centered around the Pali canon, the oldest corpus of Buddhist texts.

In contemporary studies of Theravada Buddhism in South and Southeast Asia, the term “Theravada” has been defined and redefined, and qualified by using other terms, such as Theravadin meditation, Theravadin philosophy, Theravadin psychology, Theravadin art, Theravadin iconography, and so forth.2 (I suspect that, very soon, we will see the separate categorization of Western Theravada or American Theravada.) In the context of Buddhism’s relationship to film, I believe there should be another distinctive category, called “Theravada cinema.” But what is it? What makes Theravada cinema distinctive? What separates Theravada Buddhist films from other Buddhist films?

The way Buddhism is treated in film tends to reflect the particularities of any given national Buddhist culture. Vajrayana Buddhism pervades Tibet and Bhutanese cinema,3 while Mahayana Buddhism is dominant in Korea and Japan.4 Similarly, Theravada Buddhism is central to Sri Lankan Buddhist cinema. Thus, the three popular Sinhala films discussed here—Sūriya Araṇa, Sankārā, and Uppalavannā—reflect Theravada Buddhist values and belief systems. Although they represent different genres and tell different stories, the beauty in all three of these films is generated from within a Theravada framework. All three deal explicitly with Theravada Buddhism, and the world they reveal is one enshrined in Theravada Buddhist philosophy, thought, and beliefs, made evident through the characters, images, and objects, all of which are steeped in the Theravada practice of South and Southeast Asia.

The 2004 film Sūriya Araṇa (Fire Fighters) revolves around four main characters and their love or hate for each other: an elderly Buddhist monk, a novice monk, a hunter, and the hunter’s son. In the movie, the practice of mettā (loving kindness) proves an excellent antidote to anger and the best way to resolve conflicts (if applied properly). Both audiences and critics praised Somaratne Dissanayake, the film’s writer and director, for the way his beautiful cinematography illuminated the film’s Buddhist themes. For Dissanayake, Theravada dhamma is not just a moral philosophy but is a way of dealing with contemporary living. In the film, he draws on this understanding of Buddhism, using several passages from the Pali canon to underscore the action.

The plot centers around the hunter Sediris, who subsists by hunting in a remote forest with his ten-year-old son, Tikira. The hunter prevents other villagers from entering the forest by scaring them off with false rumors of ghosts.5 One day, an elderly monk appears in the forest with a young novice monk. Sediris regards their arrival as a threat to his livelihood, since the monk teaches that animals should not be harmed. The hunter engages in various tactics to expel the monks from the village, but every effort fails. Despite the monks’ continuous love and sympathy for Sediris, the poor hunter continues to provoke the monks, until he causes a violent clash that pits hunter against monks. Meanwhile, a secret friendship develops between the novice and Tikira, challenging their boundaries and expectations. Instructed and motivated by the little monk, Tikira gradually learns how to love animals and stops killing them. The bond between the two boys becomes so indivisible that Tikira ends up becoming a novice monk himself. (Becoming a monk is a typical narrative resolution in popular Theravada cinema in Sri Lanka, Thailand, and elsewhere in Southeast Asia.)6

The social and emotional bond between the young novice monk and Tikira becomes one of spiritual communion. Sūriya Araṇa

The message conveyed in Sūriya Araṇa can be divided into two parts: a story of violence, and a touching story about the love, care, gentleness, and compassion that the young novice monk and Tikira develop for one another. They play, eat, sleep, meditate, fight, and sing together at the temple, by the riverside, and in trees. They become kalyāṇa-mitta (spiritual, virtuous, or noble friends). Their social and emotional bond becomes one of spiritual communion. Love, care, compassion, and empathy are the essence of Theravada teaching and practice, and Dissanayake realistically and movingly translates these ideas in Sūriya Araṇa.

Generally, the monastic code (Vinaya) prohibits Buddhist monks from watching movies or any form of entertainment; forget about going to the theater to see a film! But when Sūriya Araṇa was released in 2004, I was in Sri Lanka, and I saw hundreds of young Buddhist monks flock to the cinema hall to see the film, a very rare occurrence. Still, a controversy developed around the film. Some of Sri Lanka’s senior monks were outraged, questioning its appropriation of Buddhism. They were so furious that they even demanded the film be banned. Among their objections were that the older monk is seen wearing a powerful (and non-Buddhist) talisman, and the little monk is sometimes depicted playfully, doing handstands or wrestling with Tikira. For these monks, such details were inappropriate in a film about Buddhist monks. They viewed the portrayal of such behaviors as a major threat to the dignity of the sangha (the community of monks), and hence to Buddhism. Despite this harsh criticism from senior Buddhists, the film went on to achieve critical acclaim and was loved by audiences the world over. It still holds the record as the most popular film in the history of Sri Lankan cinema.

The film Sankārā (Introspection), released in 2006, developed similar themes about the tensions between monastic and lay life, and it was also a major critical success, winning the Special Jury Prize at the Cairo International Film Festival and the Best Debut Director Award at the International Film Festival of Kerala, India. Sankārā is a typical Theravada Buddhist film, in that it is based exclusively on an ancient Buddhist parable but is set in Sri Lanka’s contemporary Buddhist monastic culture. The film tells a complex story of a Buddhist monk’s encounter with sensuality and desire. It is one of many Sinhala films that are based on the Buddhist Jātaka tales, a massive body of literature of Buddhist folklore that is included in the Pali canon. These legends narrate the previous birth stories of Gautama Buddha, who appears in both human and animal form—for example, as a king, a minister, a deity, an elephant, and a monkey. These stories often have a simple but profound moral (some of Aesop’s fables are thought to be based on them), and they remain deeply rooted in the imagination of contemporary Theravada practitioners.

Sankārā narrates a breathtaking story of the inner struggle and spiritual conflict of a young Buddhist monk named Ananda who has come to a temple to restore its rundown paintings. The ancient murals he is restoring depict the Telapatta Jātaka, a legend in which the Buddha tells his disciples that a spiritual seeker should not be swayed by passion and sensual desires, and especially by beautiful women. But the monk is drawn into yearning for sensuality when he finds, and tries to return, a hairpin to a beautiful young woman. The film dwells on the universal problem of desire embedded in our minds and emotions. Buddhist psychology describes desire as the fundamental cause of human happiness and pain. Desire creates happiness and joy, but, at the same time, it produces an enormous amount of suffering in the form of anxieties, worries, and emotional turbulence.

The young monk gradually becomes more and more attracted to the woman and to the prospect of sensuality. Sankārā, Cine Films

The story focuses on the painful effects of desire and attachment. The young monk gradually becomes more and more attracted to the woman and to the prospect of sensuality. But then the paintings are destroyed. While restoring them for the second time, the monk realizes that he is caught up in the same web of desires depicted in the paintings.

Before Sankārā was released, director Prasanna Jayakody approached more than four hundred prominent Buddhist monks to review the film. Since a monk was featured as the main protagonist in the film, Jayakody wanted to be careful about religious sensitivity; he did not want to offend the sangha and jeopardize the film, as had happened with Sūriya Araṇa. Thanks to this collaboration, the monastic communities raised no objections. The monks saw the film neither as harming Buddhism nor threatening to the dignity of the sangha.

One might assume from the posters, trailers, and reviews that Uppalavannā: A Contemporary Therīgāthā is the simple story of a Buddhist nun, but this would miss the film’s profound engagement with deep religious questions. In addition to the complex religious and cultural ideas the film conveys, its story features political violence, love, romance, revenge, tragedy, and family drama—all of which go beyond the traditional definition of a “Buddhist film.” The film is set during the late 1980s, during a time in which Sri Lanka suffered from political unrest and violence because of the attacks and counterattacks between the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP), the radical communist party, and the government of Sri Lanka.

In contrast to previous films in which young monks leave the monkhood when they encounter beautiful women—a path that only brings more suffering—in Uppalavannā, the eponymous Buddhist protagonist enters a community of nuns in pursuit of spiritual happiness. She becomes a Buddhist nun following a series of tragic events, in which her attempt to find love results in suffering and death. When her hope for love is destroyed, the Buddha-dhamma becomes the only source of contentment for her.

Uppalavannā cares for a murderer after he is critically injured. Uppalavannā, Sumathi Films

The film raises some thought-provoking questions about the role Buddhism should play during political upheaval. How should a Buddhist react in the midst of societal conflict and violence? In the movie, Uppalavannā cares for an insurgent, a murderer, after he is critically injured in a fight with his former JVP comrade and seeks refuge near her nunnery. Despite the fact that the Vinaya does not allow her to touch a man, she chooses to help the murderer. For her, saving another life is far more important than upholding the Vinaya. When the stricken man tells her she has saved his life, she replies, “Not me; it’s Buddha and his teachings—love, kindness, and compassion saved you. . . . Don’t hate the society, instead extend your kindness.” As in Sūriya Araṇa, the Buddhist ideas of compassion and love are the film’s central focus. These ideas are realistically translated into film through Uppalavannā’s actual performance of an act of compassion.

The other central theme in Uppalavannā concerns femininity and the role of female monks in contemporary Sri Lanka. Generally, the depiction of women in Sinhala (Buddhist or non-Buddhist) cinema is unfavorable. Aside from a few notable exceptions, most Sinhala movies present women as morally dubious victims, temptresses, or sexual objects. In Uppalavannā, however, the Buddhist nuns are depicted as intelligent and independent. They are caretakers, teachers, and preachers, well respected by the lay community. Though this film received mixed reviews, in my view, the film is strong in its Buddhist interpretation of the story, and in its visual narration of the daily lives of Buddhist nuns. This is unprecedented in Theravada cinema.

Director Sunil Ariyaratne was well aware of the revival of bhikkhunī (female monastic sanghas) in Sri Lanka when he was making the film. As an educator and teacher at the University of Sri Jayewardenepura, Ariyaratne wanted to bring awareness to and educate Sinhala Buddhists about nuns through an intentional cinematic depiction of women in Sinhala Buddhist film. He was very effective in this attempt: the influence of Uppalavannā has been enormous. For instance, inspired by Uppalavannā’s moving story, another award-winning director, Thusitha de Silva, made a series of teledramas based on the stories and lives of Buddhist nuns in 2010.

These three films were produced not only for entertainment, but also to make a meaningful, artistic statement about Buddhism in contemporary Sri Lankan Buddhist society. Though themes of gender, desire, and sexuality have pervaded classical Theravada Buddhist literature, until the films Sankārā and Uppalavannā appeared, they have never been visually depicted in Theravada cinema. While Sankārā addresses issues of sensuality, desire, and erotic sensitivity, Uppalavannā provides a useful perspective on gender prejudices in Theravada Buddhist society. On the other hand, Sūriya Araṇa dispels the popular falsehood that meditation and asceticism are the key elements for enlightenment; rather, it suggests that love, compassion, and kindness are more important spiritual qualities. In contrast to the idealized view of a Theravada Buddhist monk or nun as free from emotions, attachments, and desires, these movies display the human nuances of monastic spiritual life.

In viewing Sankārā and Sūriya Araṇa, I am reminded of my own monastic experiences training as a monk in Myanmar and Sri Lanka; the films bring to mind my encounters with desire and sensuality and the powerful emotions that attended these experiences: feelings of joy, anger, sadness, frustration, and satisfaction. Above all, these three films are artistic triumphs that show how the value of Theravada practice can be vividly depicted through excellent writing and cinematography. These films demonstrate that Buddhism and popular cinema are not at odds, but rather, combine to create a powerful form of artistic expression. In addition to providing pleasure and entertainment, these films can strengthen the faith of their viewers.

Notes:

- Richard Gombrich, Theravada Buddhism: A Social History from Ancient Benares to Modern Colombo (Routledge, 2006); Donald Swearer, The Buddhist World of Southeast Asia (State University of New York, 2010).

- Peter Skilling, “Theravāda in History,” Pacific World: Journal of the Institute of Buddhist Studies, 3rd series, 11 (Fall 2009): 62.

- Shohini Chaudhuri and Sue Clayton, “Clouds of Unknowing: Buddhism and Bhutanese Cinema,” in Storytelling in World Cinemas, vol. 2, Contexts, ed. Lina Khatib (Columbia University Press, 2013), 157–72.

- Sharon A. Suh, Silver Screen Buddha: Buddhism in Asian and Western Film (Bloomsbury Academic, 2015); Francisca Cho “The Art of Presence: Buddhism and Korean Films,” in Representing Religion in World Cinema: Filmmaking, Mythmaking, Culture Making, ed. S. Brent Plate (Palgrave Macmillan, 2003), 107–19.

- See also Jeffrey Samuels, Attracting the Heart: Social Relations and the Aesthetics of Emotion in Sri Lankan Monastic Culture (University of Hawai‘i Press, 2010), 21–42.

- For example, Buddha’s Lost Children (2006) and Mindfulness and Murder (2011).See Ronald Green, chapter 6, “Theravāda Buddhism, Socially Engaged Buddhism,” in his Buddhism Goes to the Movies: Introduction to Buddhist Thought and Practice (Routledge, 2014), 70–81.

Chipamong Chowdhury is a Theravada monk, freelance researcher, interpreter, and teacher. He holds two master’s degrees in Sanskrit and Buddhist/South Asian studies from Naropa University and University of Toronto. Originally from Bangladesh, he travels extensively in Asia, North America, and Europe teaching on Asian Buddhist humanities, active love and compassion, and meditation.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.