In Review

The Mogao Caves as Cultural Embassies

“Wherever faith exists it will not be altered by human affairs. Those who believe deeply in the Buddha consider it possible that when he arrives the wind and waves will be calmed. Thereby he will be welcomed to the Dunhuang temples and be worshipped forever.”

—Inscription in Cave 323, Tang dynasty (618–906 CE)

Between the fourth and fourteenth centuries CE elaborately painted cave temples at Mogao, an ancient Silk Road site on the edge of the Gobi desert, thrived as a Buddhist center connecting South and East Asia. Some twenty-five kilometers southeast of the oasis town of Dunhuang in the far northwest of China, hundreds of caves were carved into a cliff face along the Daquan River and lavishly decorated with wall paintings and sculptural works. The caves’ location along one of the great trade routes of antiquity created an environment of artistic and cultural exchange between the diverse peoples who traversed this vast route, stretching from China to the Mediterranean Sea. While other historically significant places in China, such as the Great Wall, the Tomb of the First Emperor at Xi’an, and the Forbidden City, are well known to international audiences, the Mogao cave temples do not have the same renown. This is possibly due to their remote location in western China, which could also account for the caves’ extraordinary survival across two millennia.

In May 2016, the Getty Center in Los Angeles will present an ambitious exhibition on the spectacular painted cave temples.1 Through precious works of art loaned from European museums and the cave themselves, as well as photographs, videos, virtual immersion, and elaborate replica caves, the exhibition tells the story of one of the world’s greatest cultural treasures—its genesis and proliferation, its encounters with destructive threats from humans and nature, its miraculous survival over the course of more than fifteen hundred years, and most importantly, the intensive contemporary efforts to conserve and protect the caves for future generations. This exhibition highlights the modern history of the Mogao cave temples and presents their current situation, elaborating on the Getty Conservation Institute’s continuing collaboration with the Dunhuang Academy to address the preservation challenges which the site faces. To illustrate the life of a wall painting and trace its eleven-hundred-year history—from creation to deterioration to conservation—the exhibition recreates a portion of a wall from one of the caves.

The challenges for the exhibition curators were, at times, truly mind-boggling. How to authentically present the wonders of the site to viewers halfway around the world? How to portray the unusual cultural diversity of the site to viewers who may have never heard of the site’s ancient ethnic groups? Finally, and most challengingly, the curators grappled with the question of how to retain the spirituality and meaning of these works of art, contextualizing Buddhist practices for a modern American audience.

The cave temples of Mogao, carved into the cliff face along the Daquan River. The nine-story temple can be seen in the center. Photo by Sun Zhijun. © Dunhuang Academy

The nine-story temple (Cave 96) houses a colossal Tang dynasty Buddha statue some thirty-three meters high. Mogao caves, Dunhuang, China. © Dunhuang Academy.

Dunhuang was founded around 111 BCE as a military outpost to guard China’s northwestern frontier against raids from the Xiongnu, nomads from the Central Asian steppe. It lay near the far western reaches of the defensive fortifications now known as the Great Wall, which helped protect the frontier and which included stretches of the Central Asian trade routes. The word “Dunhuang” means “Blazing Beacon”; the site was named for the watchtowers placed at intervals along the frontier’s defensive wall. At the beginning of the first millennium, Buddhism spread north out of India along these trade routes, traveling east to the Silk Road oases, passing through Dunhuang on its way further into China. Based on the surviving evidence of the art at Dunhuang, it seems that all of those who came to Mogao to visit, to reside, or to govern the region practiced, tolerated, or actively supported the local worship of Buddhism.

At its apogee in the Tang dynasty, the fame of the Mogao cave temples extended from the Chinese heartland to the far western kingdoms of Central Asia. Ornate temple fronts stood along the cliff face, while walkways allowed access to the upper-tier caves. As camel caravans arrived along the Daquan River in front of the temples, silk banners fluttered, gongs chimed, , offerings were made, and monks from the local monasteries ushered travelers into the caves. During this period, other cave temples were created at various adjacent sites, including Kizil, to the west, dating two hundred years earlier than those at Mogao, and Bezeklik, to the northwest.

Many stories can be told in an exhibition about this extraordinary place, in ancient times a cultural crossroads, today a small city with looming potential for touristic expansion. The wall paintings in the 492 painted caves at Mogao depict the changes undergone by Buddhism upon entering China—how, for example, the Bodhisattva known as Avalokiteśvara was transformed into the figure of Guanyin in China—but the images also provide detailed information about everyday life. Formal depictions of Buddhist sutras and parables intended to guide and to convert allow contemporary viewers to glimpse the power the art would have possessed when beheld by pilgrims and merchants, perhaps weary after the dangers and hardships of crossing the desert wastelands on horseback and camel.

Cave 85, view of the interior, Late Tang dynasty (848–907 CE). Mogao caves, Dunhuang, China. © Dunhuang Academy.

Cave 85, detail of wall painting of a dancing figure. Late Tang dynasty (848–907 CE). Mogao caves, Dunhuang, China. Photo by Lori Wong. © J. Paul Getty Trust

Cave 85, detail of wall painting of musicians. Late Tang dynasty (848–907 CE). Mogao caves, Dunhuang, China. Photo by Lori Wong. © J. Paul Getty Trust

The curators’ task was to make this colorful past come alive and have meaning for the present. To do so, the curators chose a selection of extraordinary objects from the site: manuscripts and scrolls, paintings on silk, banners, drawings, and sculptures loaned by the British Museum, the British Library, the Musée Guimet, and the Bibliothèque nationale de France. Most of the objects have rarely, if ever, traveled, and none have ever come to the United States. All works or art were originally from the hidden Cave 17, also known as the Library Cave, where more than 40,000 objects were sealed away for more than a millennium before their rediscovery in 1900. Shortly thereafter, explorers from Britain, France, Russia, Japan, and the United States came to Dunhuang, where they obtained thousands of these objects to take to their home countries. The explorers obtained these objects during the final years of the Qing dynasty, as the old order crumbled under the combined onslaught of foreign interventions and internal pressure to modernize. These treasures enable us to comprehend more broadly the creative, intellectual, and spiritual environment of early medieval China and to understand the considerable cultural impact of the transmission of Buddhism along the Silk Road.

The artistic representation of Buddhist themes and iconography is a central element in the exhibition. The objects originally from Dunhuang were created to address and fulfill religious purposes. Carefully selected art works in the main galleries of the exhibition present characteristic iconic images. Travelers are shown making their way along the Silk Road to transmit religious knowledge. Itinerant monks bear sacred texts and relics, transporting the early physical sources of Buddhism over long distances. Striking cultural diversity is demonstrated by these manuscripts: a Buddhist pilgrim text records a tenth-century monk’s journey from northern China to northeastern India; one rare manuscript contains a Hebrew prayer; a book of omens is written in Old Turkic; and a Tibetan sutra has a Chinese commentary. The exhibition demonstrates how Buddhist texts prescribed rules governing artistic practice: many display stunning examples of freehand sketches, stenciling powders, and woodblock prints (from the Library Cave).

One of the key objects at the exhibition is a copy, dating to the year 868 CE, of the Diamond Sutra, a sacred Mahāyāna Buddhist text. This copy is among the world’s earliest extant printed texts. Commissioned by a man named Wang Jie on behalf of his parents, it is the first known complete book bearing a date. The large frontispiece, which depicts the Buddha in Jeta Grove preaching to the elder disciple, Subhūti, is followed by a “speech purifying” mantra (jing kouye zhenyan), dedications to eight vajra deities, Kumārajīva’s translation of the influential Mahāyāna text, another mantra, and finally the single-line dated colophon—making it one of the world’s oldest dated complete printed books, if not the earliest. The book’s sophisticated woodblock-printing on paper points to the mature publishing industry that existed in China at this early date.

Diamond Sutra, 868 CE, ink on paper. London, British Library, Or.8210/P.2. Copyright © The British Library Board.

Among other notable pieces in the exhibition are polychrome wooden sculptures of two of the Heavenly Kings, martial deities tasked with guarding the four quarters of the Buddhist universe.2 These warrior figures (lokapāla) frequently appear at the thresholds of Buddhist painting and sculptural programs. The mirrored poses of these two figures indicate that they were stationed opposite each other. Their feet, which appear to be raised, would originally have rested on a vanquished demon or submissive beast. Although much of the vibrant colors of paint on the figures has now been erased, their massive bodies still retain a sense of their status as divine warriors who possess agility and grace. This is reinforced by the wonderfully animated facial expressions that make the kings appear fiercely resolute and a bit scary.3

Other selected works, such as a ninth-century painting on silk of a bodhisattva with a banner leading a Tang lady into the afterlife, illuminate how artists depicted personal connections between the divine and the patrons who commissioned their work. The variety of media chosen for this exhibition—paintings, tapestries, banners, wooden sculptures, manuscripts, and printed works on paper—reflect the complex ideas, beliefs, and artistic styles of the diverse populations who traveled through and traded and lived at the site. Not just exquisite objects, these works tell the stories of this place and the central role of Buddhism in the art which was created there. And, this exhibition illustrates the dynamic way that a knowledge of art history combined with conservation science deepens our collective understanding and helps to safeguard our world’s heritage.

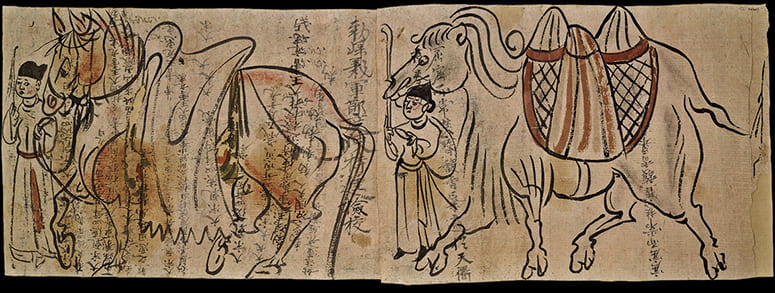

Tribute horse and camel, ca. late 800s CE, ink and pigments on paper. London, British Museum, 1919,0101,0.77. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Guiding bodhisattva, ca. 850–900 CE, ink and pigments on silk with gold leaf. London, British Museum, 1919,0101,0.47. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Creating the enormous replica caves that are the center of the exhibition was a complex process, drawing on more than two decades of collaboration between the Getty Conservation Institute and the Dunhuang Academy in China. Since its inception in the 1940s, the Dunhuang Academy has created exact hand-painted, full-scale replica caves to convey the art to the general public. Some of the most exciting moments during the Getty exhibition team’s recent visits to the academy were spent with the artists who were engaged in making the replica caves and other reproductions of the wall paintings or sculptures. In China, replication is considered an important way to master the traditional practice of Chinese painting. Creation of the replica caves is an integral aspect of the Dunhuang Academy artists’ intellectual and spiritual engagement with their work.

The process of fabricating a replica cave can take years, involving a number of steps. First, the shell of the replica cave is constructed to the exact dimensions of the original; the cave’s interior is photographed and printed at original scale; and the printed images are traced with a pencil. Working in the cave itself, the artist then studies the original paintings, modifying the tracing to correct the scale and any distortion. Capturing the use of line and the spirit of the original painting, the artist uses a brush to create a unique contour line drawing on top of the reworked tracing, transferring the drawing onto fine, colored xuan (long-fiber mulberry-bark) paper.

To replicate the texture of the Dunhuang murals, clay from the Daquan River is used to size the paper, forming a base which is then brushed onto the base layer of paint several times. The outline drawing is then mounted onto a board and retouched. Because of the many historical styles present in the Mogao cave temples, a range of brush and coloring techniques and pigments are used to complete the paintings. Once dry, paintings are individually mounted on the wooden shell of the replica cave. Replica sculptures are made on a framework of wood, with bundled thin reeds providing bulk. The features and garments are then modeled in clay and painted with the same pigments as the murals. The artists making the replicas faithfully reproduce the current condition of the cave, showing areas of loss and deterioration. In this way they provide a documentary record, providing visitors with a near-authentic experience of the scale and interiors of the caves.

Three replica caves created at the Dunhuang Academy will be set up on the Getty Center’s arrival plaza for visitors to enter and experience. The caves’ artists will travel to Los Angeles for their installation. The replica caves were selected for their diverse content, which provides a hint of the broad range of subjects and styles seen at Mogao. One of the caves, reproduced from a fifth-century CE original, contains a bodhisattva sculpture identified as Maitreya, the future Buddha, and five painted stories of the Buddha’s past lives, or jātaka tales. Another, from the sixth century, contains the earliest inscription of any cave at Mogao, which takes meditation as one of its themes. Constructed in the square vihāra, or monastery, style from India, its wall paintings incorporate Hindu and indigenous Chinese deities into a Buddhist context. A cave from the eighth century CE contains a truncated pyramidal ceiling with a peony motif, illusionistic decorative tent hangings in the corners, and several miniature Buddhas. The cave includes stories of Amitābha, a monk who became a Buddha in the process of achieving enlightenment.

The treasures exhibited at the Getty provide a broad survey of the creative, intellectual, and spiritual environment of early medieval China, as well as the considerable cultural impact of the transmission of Buddhism along the Silk Road. A common perception is that globalization and pluralism are uniquely modern. This exhibition demonstrates that the exchange of goods, objects, commodities, knowledge, and spiritual practice extends far back into history. The cultural diversity of the site can illuminate the present. Just as Dunhuang was a cultural crossroads in ancient times, today it is a small city with looming potential for touristic expansion. New waves of visitors to the caves are streaming into present-day Dunhuang, themselves eerie replicas of the travelers and traders depicted in the ancient cave murals.4

Notes:

- This is the first North American exhibition to explore the iconography, art, and environment of this UNESCO World Heritage Site. The Robert H. N. Ho Family Foundation is the presenting sponsor. The lead corporate sponsor is East West Bank. The Luce Foundation is the lead sponsor. Lead curators include Neville Agnew, senior principal project specialist, Getty Conservation Institute; Marcia Reed, chief curator, Getty Research Institute; Fan Jinshi, director emerita, Dunhuang Academy; and Mimi Gardner Gates, director emerita, Seattle Art Museum and chairman of the Dunhuang Foundation.

- These sculptures are borrowed from the Musée Guimet in Paris.

- The French scholar Paul Pelliot acquired these sculptures during his 1906–9 expedition, together with a collection of documents and paintings; according to his records, they were removed from a local temple rather than from the Library Cave.

- Exhibition publications include the catalogue Cave Temples of Dunhuang: Buddhist Art on China’s Silk Road, and a second edition of Roderick Whitfield, Susan Whitfield, and Neville Agnew, Cave Temples of Mogao at Dunhuang: Art and History on the Silk Road. The exhibition will be accompanied by an array of programs, including public lectures, an international conference on current research on the Mogao grottoes, public programs, musical performances, and films. For a full schedule of events, visit www.getty.edu/research/exhibitions_events/exhibitions/cave_temples_dunhuang.

Marcia Reed is chief curator at the Getty Research Institute. Her research focuses on seventeenth- and eighteenth-century illustrated books and prints, with special interest in the China Trade. Past Getty exhibitions include China on Paper: European and Chinese Works from the late Sixteenth to Early Nineteenth Century (2007).

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.