In Review

The Whole Home Is Lifted

By Kimberley Patton

Meanwhile the floor, the roof, the opposed walls, the furniture, in their hot gloom: all watch upon one hollow center. The intricate tissue is motionless. The swan, the hidden needle, hold their course. On the red-gold wall sleeps a long, faded ellipsoid smear of light. The vase is dark. Upon the leisures of the earth the whole home is lifted before the approach of darkness as a boat and as a sacrament.

—James Agee, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men

Years ago, a hellish storm from the sea placed its lips over the ancient chimney of my house, and blew across the opening like the neck of a bottle. It blew until the entire shaft roared. All night, this never stopped. Three hundred years ago, my house was built from shipyard salvage timbers. One of these, a support column in the keeping-room, is the mast of a colonialera brigantine. Without a shiver, the boathouse simply roped itself in tighter against the storm. It floated up and rode the salt gale safely into the smoke of dawn. When in the morning I stepped out onto the street and saw the winds’ ravages, I knew that the house had fought against Goliath and prevailed.

Homelessness has become a permanent feature in the American spectrum of social ills. A painful index of human indignity, the lot of the refugee and exile, homelessness has not yet been conquered through social engineering, but rather has settled like a deep infection into our national body.

What does “home” mean, and what is the source of its power?

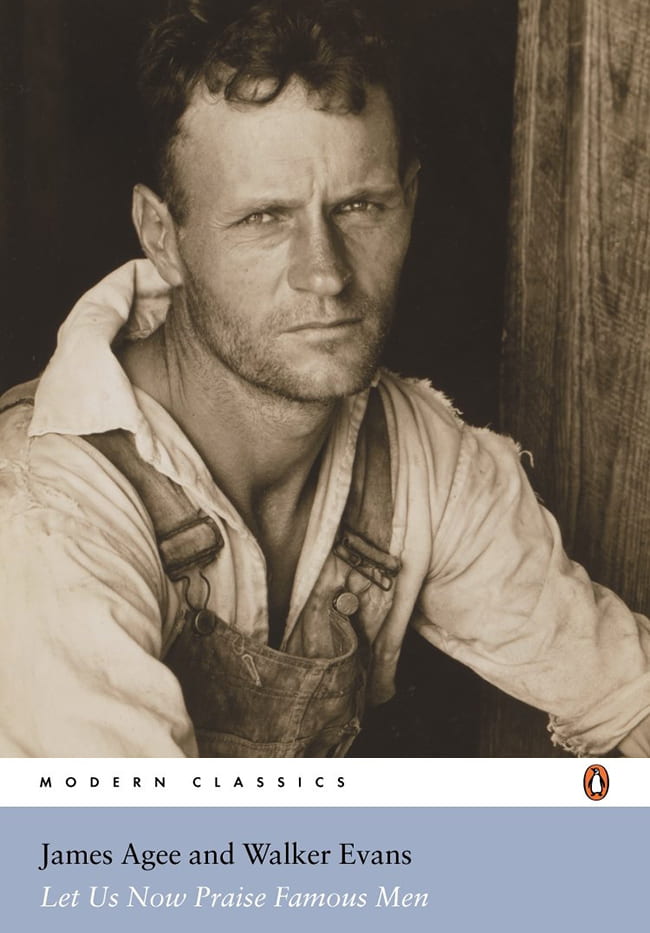

Ironically titled, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men was the self-conscious, renegade prose-poem of the American writer James Agee. Assigned (and ultimately rejected) by Fortune magazine as a report on the plight of the impoverished sharecroppers of Alabama, it was written in 1936 and illustrated by the stark photographic essay of Walker Evans, who accompanied the author in his travels. It became one of the most famous of American Depression-era works, neither novel nor journalistic essay, but something of a different genre entirely. “The nominal subject is North American cotton tenantry as examined in the daily living of three representative white tenant families,” wrote Agee in the preface; but “more essentially,” he admitted, “this is an independent inquiry into certain normal predicaments of human divinity.”

The work described the home not merely as an inadequate shack, but also as an existential rebellion against chaos and despair. Out of Agee’s journalistic sermon came his insistence that the structures we inhabit are not merely physically but also spiritually crucial to our lives as human beings. In Agee’s vision, we are frail and the world is ruthless, “immane and outrageous, wild, irresponsible, dangerous-idiot.” Built in an immediate environ that is surely an outrage, is the shack of a tenant farmer a courageous sanctuary? Or is it a pathetic defense against the night and the oppressive anarchy of circumstance? Agee answers that it is both. The houses he inhabits in Cookstown embody both the fearful immanence and the radical transcendence of human life.

The house of one family, George and Annie Mae Gudger and their children, is a lamp. It is a boat. It is a sacrament. The lamp is lifted before the approach of darkness. The boat is lifted over the dim seaflood of poverty. The sacrament is lifted to heaven in the face of gnawing, secular time. These are ancient symbols, whose origins are biblical and earlier. By using each of them to describe one particular home, the place he lived, Agee implies certain accrued symbolic meanings. These, in turn, are intertwined throughout Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. Through Agee’s poetic words and the aching, honorable lens of Walker Evans, we are shown that the house is only a “human shelter, a strangely lined nest, a creature of killed pine, stitched together with nails into about as rude a garment against the hostilities of heaven as a human family may wear.” Yet it is also a lamp, a boat, and a sacrament. At night, by starlight, Agee saw that in the silence of the cessation of almost unceasing labor, “the bone pine hung on its nails like an abandoned Christ.”

The symbolic language James Agee uses to describe the wooden-frame house of an Alabama tenant farmer family bespeaks his deep ambivalence toward traditional Christian doctrines, along with his simultaneous inability to abandon them as a deep well of signification. In the course of his documentary novel, the Anglo-Catholic Agee is himself forced to abandon Christ: even the redemptive passion of the single, renowned Crucifixion of the Lord cannot atone for the obscure crucifixions that take place daily before his eyes in Alabama. Let Us Now Praise Famous Men is thus an anguished testimony of religious faith destroyed by unexpected attendance upon the monotonous and soul-wrecking experience of others. Through this searing book, Agee brought to national attention the kind of suffering of the kind that destroyed the faith of Dostoevsky’s Ivan. I have always treasured the book’s paradoxical marriage of faith and despair, its stark willingness to dwell between contradictory opposites without trying to resolve them. And I always appreciate its literary beauty—framing a horrific struggle with theodicy—by remembering the words of The Book of Common Prayer, for this liturgical consciousness was in Agee’s background, informing his language, his theology, and his most radical confrontations with heaven.

The onset of night is the setting for the passage quoted at the beginning of this essay. Twilight is the time most appropriate for Agee’s inquiry. It throws the house, bright enclave of family law and experience, into sharp relief. Night comes, but the lamps are lit, and supper prepared. There is a miniature order amid the vast dark outside. Night represents the lawlessness of fate, “the pity, the abomination of the crimes [man] is to sustain,” the pain and confusion that afflicts each of us from birth. This is most clearly seen when the exigencies of the surrounding world are the worst, as for a family like the Gudgers. For them, night is poverty, the struggle of cotton, illness, monotony, weariness, hunger, and dirt. They have no more control over these things than the human race has over the onset of night. Night is a tyrant.

Yet the home is the tabernacle of rebellious serfs. There is also to each of us, Agee insists, a “miraculousness” and a “royalty.” We harbor an inborn yearning that is aesthetic. In the face of chronic futility Agee observes that human beings create order and beauty; we cannot do otherwise, even if these are of the crudest sort. The internally consistent patterns of crime and insanity are desperate attempts by the beleaguered to create an ordered image—however inadequate—by which to live.1 The inborn aesthetic will not be extinguished; and total psychic chaos or randomness is very rare.

The onset of night, before which the Gudgers’ bedroom waxes red-gold, becomes for Agee a metaphor for the human condition: life in this “storm of torture.” Thus the construction and habitation of a home becomes an act of defiance against this storm. The Gudgers’ house is a fundamental, unconscious assertion of the sublime, of our deep unwillingness to be crushed by anarchy. Night comes, but the cow “suspends upon creation . . . the wide amber holy lamp of her consciousness,”

. . . and dinner, and they are all drawn into the one and hottest room, the parents; the children; and beneath the table the dog and the puppy and the sliding cats, and above it, a grizzling literal darkness of flies, and spread on all quarters, the simmering dream held in this horizon yet overflowing it, and of the natural world, and eighty miles back east and north, the hard flat incurable sore of Birmingham.

Agee gives us this paradox: the house, a skeleton of cheap pine, is perishable. Yet for him it is also eternal, light-bearing, and god-bearing, theotokos, as the young Jewish peasant Mary was said to have been, a crucible out of a woven basket. The Christian doctrine of the Incarnation points to this bearing of the divine within the perishable as a great signal on God’s part that he is in us, and we are in him: the world will not ultimately be handed over to dark chaos. So the Gudgers’ home, like the Incarnation, is a supreme expression of the interlocking of the human and the divine. Agee presents himself as witness: Like the doctrine of the Second Coming, the home is a promise of hope that the God within us will keep the night at bay.

I.

And the light shines in the darkness, And the darkness has not overcome it.

—John 1:5

Perhaps the most pervasive entity in Agee’s description of the farmers’ houses in Cookstown is light. The Gudgers’ house is seen by many different lights, “in slanted light, all slantings and sharpenings of shadow: in smothered light, the aspect of bone, a relic,” in the “slow complexions of marchings of pure light” which stalk the boards, “all of this framed image a little unnaturally brilliant and vital, as all strongly lighted things appear through corridors of darkness.” The sun shines and consecrates the house by day; yet more important is the haunting image of the lamp lit in the evening, which casts a surrounding halo on the scene, drawing the family into its golden triptych. It is the lamp which creates the iconostasis during Agee’s unplanned visit to the Gudgers at the time of the rainstorm at night, when he struggles in from

the crumpled edge of the gravel pit, the two negro houses I twisted between, among their trees; they were dark; and down the darkness under the trees, whose roots and rocks were under me in the mud, and shin-deep through swollen water. . . .

And this is how we see Annie Mae and George Gudger sitting with him while he gratefully eats biscuits and leather-eggs and jam,

in the lamplight in the presence of the walls of the house and of the country night the beauty and stress of our tiredness, how we held quietness, gentleness, and care toward one another like three mild lanterns held each at the met heads of strangers in darkness: such things, and these are just a few, I have not managed to give their truth in words, which are a soft, plain-featured, and noble music. . . .

Like the house, the lamp is at once the center and the catalyst for a brief yet profound human encounter.

The comfort and reassurance offered by a home at night, brightly lit and closely indwelled by the members of a family, is remarked by George Orwell in The Road to Wigan Pier. Against the ugly setting of an industrial and mining town and the brutal life-agenda sustained by its citizens glows the quickly lost, jewel-like scene in which Orwell finds their hearts:

In a working-class home . . . you breathe a warm, decent, deeply human atmosphere which it is not so easy to find elsewhere. I have often been struck by the peculiar easy completeness, the perfect symmetry, as it were, of a working-class interior at its best. . . . Curiously enough, it is not the triumphs of modern engineering . . . but the memory of working-class interiors . . . that reminds me that our age has not been altogether a bad one to live in.2

The symmetry of the interior, which Agee calls “most naive, most massive symmetry and simpleness,” also enchants Orwell.

Yet it is the lamp, lifted up before the approach of darkness, that finally leads us to the tragedy of the Gudgers’ small house, or of any home. In the gut of the night, threatened by imaginary bats, accompanied only by “lamplight here, and lone, and late,” Agee is aware of how fragile the lamp is, as is the shelter it illumines. And he knows without relief how vast the void that engulfs the shelter: “. . . above that shell and carapace, more frail against heaven than fragilest membrane of glass, nothing, straight to the terrific stars.” As he says, “small wonder how pitiably we love our home, cling in her skirts at night, rejoice in her wide star-seducing smile, when every star strikes us sick with fright: do we really exist at all?”

What is the Gudgers’ house? It serves to shelter, to consecrate, to light up the night and make order of a small space within it; it also has the function of hopelessly separating the Gudgers from the rest of humanity—just as their possessions, the rose talcum powder, the cast-iron sewing machine, the kitchen dipper, toothless comb, and plaque of the Virgin, distinguish them from other families. Our brightly lit American homes are tight-locked boxes, segregating us from one another.

And thus, too, these families, not otherwise than with every family in the earth, how each, apart, how inconceivably lonely, sorrowful, and remote! . . . so that even as they sit at the lamp and eat their supper, the joke they are laughing at could not be so funny to anybody else . . . and the people next up the road cannot care in the same way, not for any of it: for they are absorbed upon

themselves. . . .

The lamplight drawing together James Agee with George and Annie Mae Gudger, for the period of time that the natural limits of his mission and their fatigue would allow, assumes a sadder meaning. “The lamplight pulses like wounded honey through the seams in the soft night and there is laughter: but nobody else cares.” The house as a lamp becomes a cruel, petty thing, an irony. For “[w]hile they are still drawn together within one shelter around the center of their parents, these children together compose a family.”

But this is only temporary; children grow up and become alien to their homes and to their parents, who age, choke, and die. This too is night; time has its own anarchy. Therefore,

All over the whole round earth and in the settlements, the towns, and the great iron stones of cities, people are drawn inward within their little shells of rooms, and are to be seen in their wondrous and pitiful actions through the surfaces of their lighted windows by thousands, by millions, little golden aquariums. . . .

Little golden aquariums! A far cry from altars.

II.

The flood continued forty days upon the earth; and the waters increased, and bore up the ark; and it rose high above the earth. The waters prevailed and increased greatly upon the earth; and the ark floated on the face of the waters.

—Genesis 7:17–18

The sea is a primordial symbol of chaos and danger. In the Babylonian creation epic Enuma Elish, the hero Marduk must slay the sea-monster Tiamat before law and light can rightfully rule. In Genesis, before anything was created in the new cosmos, “darkness was upon the face of the deep” (Genesis 1:2); God “separated the waters from the waters.” (Genesis 1:6). When God purges the earth of her corrupt human constructs, he does so by flood. The human race is submerged, and the cosmos reverts back to its original anarchy. God commands Noah to build an ark of balsa wood, a floating raft which for 40 days preserves the only life left on the planet. The waters increased, and “bore up” the ark, just as in our passage “the whole home is lifted before the approach of darkness.” Lifting is an act of preservation and consecration, as in the Catholic and Anglican liturgies: “Lift up your hearts.” “We lift them up unto the Lord.”

Like a boat, the Gudgers’ house is built of wood, watching upon “one hollow center.” Like wood that has been covered by salt water, it is polished:

the wood of the whole of this house shines with the noble gentleness of cherished silver, much as where . . . along the floors, in the pathings of the millions of soft wavelike movements of naked feet, it can be still more melodiously charmed upon its knots, and is as wood long-fondled in a tender sea.3

Like a boat, like Noah’s ark in the world-destroying flood, the house is a delicate harbinger of life amid death-waters. A boat has no physical or metaphysical right to survive; it is essentially a whistle at Poseidon and at Hades, a prayer tossed upon a fickle tide. This is also true of a house. A boat is the simple construction of wood and hope that the waters of anarchy will not rise and drown us. So is a home.

The metaphor of boat occurs frequently in Agee’s narrative. In “On the Porch: 1,” when night has fallen and all are asleep, “[t]here was no longer any sound of the sinking and settling, like gently foundering, fatal boats, of the bodies and brains of this human family through the late stages of fatigue unharnessed or the early phases of sleep.”

Human souls are so much like boats; boats are like houses; and a house is like a human soul. Thus the Gudgers’ house is the land-locked version of a boat upon the sea. Agee’s metaphorical language requires that we consider the size of the sea, as compared with the size of a boat; that we consider the power and depth of the sea in relation to the strength of a boat, so easily smashed. In the light-night incident when Agee wakes the Gudgers, we recall that the haggard journalist comes in out of a torrent.

After he settles down in his own room with the stench of the mildewed Bible, the scrabbling of the hungry bedbugs, and the parade of his own thoughts, he is at first impressed with the room’s ordinariness:

this was a room of a human house, of a sort stood up by the hundreds of thousands in the whole of the country; the sheltering and home of the love, hope, ruin, of the living of all of a family, and all the shelter it shall ever know, and since of itself it is so ordinary, so universal, there is no need to name it as a barn, or as a box-car.

Ordinary as one boat of a fleet anchored in a great harbor, yet as unique and valiant as a small schooner yawling and pitching around the Cape of Good Hope.

But here, I would only suggest how thin-walled, skeletal and beautiful it seemed in a particular time, as if it were a little boat in the darkness, floated upon the night, far out on the steadiness of a vacant sea, and felt the presence of the country round me and upon me.

The sea, while it threatens the lives of those in the boat, at the same time “lifts it up,” as both Agee and the author of Genesis noted, the latter writing of the ark floating upon the breast of the flood. The boat is lifted up as would be an offering. There is no sailing upon the sea without a boat, and, Agee implies, no survival in the world without a home—wooden and hollow, a fragile and symmetrical space in the water. Without symmetrical construction, a boat would founder.

Biblical archaeology was electrified 21 years ago by the discovery of a first-century wooden fishing boat in the mud of the Sea of Galilee. In the history of religions, only one is supposed to have “walked upon the water”—why? In the Christian religious imagination, he needed no pine boat, and thus, by transitivity, no home, no survival raft of family, no shelter against the chaos. It did not threaten to drown him as it would us. In the story, the waves bore him up directly.

III.

Almighty, everlasting God, let our prayer in your sight be as incense, the lifting up of our hands as the evening sacrifice. Give us grace to behold you, present in your Word and Sacraments, and to recognize you in the lives of those around us. Stir up in us the flame of that love which burned in the heart of your Son as he bore his passion, and let it burn in us to eternal life and to the ages of ages.

—The Book of Common Prayer, “An Ozer of Worship for the Evening”

Why does Agee say that the Gudgers’ house is “lifted as a sacrament”? In The Bible and the Liturgy, Jean Daniélou calls sacraments “symbols of heavenly realities” and sacramental symbols “the relationship of visible things to invisible”—”the sacraments carry on in our midst the mirabilia, the great works of God.”4 By the traditional seven sacraments of the church—baptism, confirmation, the Mass, absolution, matrimony, holy order, and extreme unction—Christians are reminded of the intersection of the human and the divine realms.

For Agee, this is what a home means. Repeatedly, he refers to the Gudgers’ house as a “tabernacle.” He prefaces the section “Shelter” with the Psalmist’s “I will go unto the altar of God.” In the front bedroom, he calls the fireplace and mantel “the altar,” and the table drawer “the tabernacle.” The house is simple; it is holy. Like the sacrificial host, it is lifted up for the world to see and like a sacrament, in its very simplicity, it implies a wealth of meaning, as Alan Watts says:

The concept of sacrament is of special importance because it is an almost perfect definition of a mythological symbol. For a sacrament is no mere sign, no mere figure for a known reality which exists in our experience, quite apart from its sign. A sacrament is not only a symbol; it is also for itself, and holy independent of its symbolism. Each of its actions and objects imply a universe of meaning. It is more than allegory. Its truth is unto itself.5

So the Gudgers’ home is

. . . a house of simple people which stands empty and silent in the vast Southern country morning sunlight . . . [which] shines quietly forth such grandeur, such sorrowful holiness of its exactitudes in existence as no human consciousness shall ever rightly perceive, far less impart to another.

Just as a sacrament is not rightly perceived by us as a known reality, something which draws on our experience and is intelligible to the intellect or passion, so the sanctuary of a house defies our conscious understanding. It must be perceived spiritually, for like a sacrament, “it is not an allegorical action, a way of representing something which the participants ‘understand’ in some other and more direct manner. The material ‘part’ of a sacrament, the ‘matter’ which it employs and the ‘form’ in which it is employed, always signifies what is otherwise unknown.”6 The scope of the power of “home,” whether in dreams or in social policy, probably remains unknown.

Agee describes the Gudgers’ house as “compounding a chord of four chambers upon a soul and center of clean air,” where all the walls “watch upon one hollow center.”

The essence of the home and of the people dwelling in it is indefinable by any one material symbol, no matter how evocative. What is this “soul and center of clean air”? It is the gyre of inner being, whistling, empty, whose nature Agee does not really know, as he cannot penetrate it. He can only describe the things which circumscribe it. Let Us Now Praise Famous Men plays for us a symphony of the peripheral. In the objects and actions that constitute the physical environment of the farmers, Agee expresses the spirit that animates and sanctifies them. Yet the spirit itself cannot be seen or spoken of, any more than the hollow center of the house can be described other than in terms of the objects which are contained within its threshold and walls.

In the Hebrew Bible, the temple of Jerusalem is often described as “the house of the Lord.”7 And in the New Testament, Luke’s Gospel tells us of a woman who lived in the temple, and made it her home (Luke 27). The archaeology of the ancient Mediterranean seems to bespeak a conflation of home and shrine long ago. For example, in the Homeric citadel of Tiryns, the eighth- or seventh-century BCE temenos (the archaic shrine, from temnein, to “cut into pieces”; a sanctuary was a place cut apart from the civic, profane area) directly evolved from the earlier “hairpin” house-model of the time, with the cult statue replacing the centrally situated door. The idea of home as tabernacle is an old one, predating the exigencies of the Great Depression.

At a bright time in sun, and in a suddenness alien to those rhythms the land has known these hundred millions of years, lumber of other land was brought rattling in yellow wagonloads and caught up between hammers upon air before unregarding heaven. . . .

A house is erected in violence upon the earth and passes quickly from it:

. . . a hollow altar, temple, or poor shrine, a human shelter, which for the space of a number of seasons shall hold this shape of earth denatured: yet in whose history this house shall have passed soft and casually as a snowflake fallen on black spring ground, which thaws in touching.

Like the lilies of the field, the house is fodder for the furnace; it will be consumed by time. But as long as it survives, indwelled by members of a family, it is a temenos; like a lamp, a boat, and a sacrament, it is set apart from the profane darkness, affirming the divine investment on our side in that struggle. “If I say, ‘Surely the darkness will cover me, and the light around me turn to night,’ darkness is not dark to you, O Lord; the night is as bright as the day; darkness and light to you are both alike” (Psalm 139:11–12).

Agee’s is a problematic faith, a Christianity lost to the misery of the people he dwelled among. He cannot affirm Christ as Redeemer, because that would dishonor their cataclysm:

. . . those three hours upon the cross are but a noble and too trivial an emblem how in each individual among most of the two billion now alive and in each successive instant of the existence of each existence not only human being but in him the tallest and most sanguine hope of godhead is in a billion choiring and drone of pain of generations upon generations unceasingly crucified.

Agee cannot tolerate the proposed efficacy of the atonement of Christ, that one who, like the Gudgers’ house, was “caught up between hammers upon air before unregarding heaven.” In the face of the despair and hardship everywhere around him, in Cookstown and the world, Agee shakes Jesus of Nazareth, demanding, “Of what value was your murder? These are all murdered a thousand times over, again and again, before they finally sink into the earth forever. Whose suffering do you really bear; whom have you redeemed?” The “Light of the World” seems nowhere visible in the dark night of need swallowing up the disenfranchised of the world, as they sleep and as they wake.

Yet Agee cannot entirely renounce his faith. Neither could the Gudgers. They could not not hope.

“The whole home is lifted before the approach of darkness as a boat and as a sacrament.” If heaven were truly unregarding, the whole home would not be lifted. Agee reveres what he sees as divine, and hopes that it is God-given. If not, the miracles of human perseverance he witnesses, while still beautiful, would ultimately be futile. Before the approach of night, because of our homes, we do not all go out to lament beneath the sky, scavenging the streets for blood or food. Instead, we light the lamp, and keep it burning; we pilot the boat and congregate. This, for Agee, is what “home” means.

Lighten our darkness, we beseech thee, O Lord; and by thy great mercy defend us from all perils and dangers of this night; for the love of thy only Son, our Savior, Jesus Christ.

—The Book of Common Prayer, “An Order of Worship for the Evening”

For 20 centuries, Christians have kept the watch, as did Agee through the Alabama night. Yet, as Dostoevsky wrote, “Lord, we have seen no sign.”

Notes:

- I am reminded of the one neatly made bed at Massachusetts Mental Hospital, where I worked as a volunteer many years ago. Surrounded by 60 unmade, tormented beds, it was next to a window where, in the morning light, I saw that the patient had lined up a menorah, a Star of David, and a candle.

- George Orwell, The Road to Wigan Pier (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1958), 117–118.

- For a certain period in colonial times, around 1750, there was a certain interchangeability between ship and home: Trees cut in the New World of over a foot and a half in diameter had to be surrendered to the royal ship-builders for use as masts. These came to be known as “King’s timber.” Many colonists simply split the large trees and laid them down as floorboards.

- Jean Daniélou, S.J., The Bible and the Liturgy (University of Notre Dame Press, 1956), 13, 5.

- Alan Watts, Myth and Ritual in Christianity (Beacon Press, 1968), 200.

- Ibid.

- As, for example, in Psalms 26:8; 27:4; 65:4.

Kimberley Patton is Professor of the Comparative and Historical Study of Religion at HDS. She is the author of the recent book The Sea Can Wash Away All Evils: Modern Marine Pollution and the Ancient Cathartic Ocean (Columbia University Press).

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.