In Review

The Gospel of Guantánamo

Mohamedou Ould Slahi’s Guantánamo Diary recounts the worst of American torture while offering a compelling vision of faith and reconciliation.

By Marisa Egerstrom

In Guantánamo Diary, Mohamedou Ould Slahi describes the months of brutal interrogation, sleep deprivation, beatings, starvation, and sexual assault he endured at the U.S. government’s notorious detention center in Cuba. But the climactic descriptions of what it took for him to “break” are almost easy to miss, because they’re not the obscene, spectacular horrors of the boat ride in which he was beaten and made to drink saltwater, nor are they the viciousness of the threats screamed at him. Rather, they come in quiet moments in the too-silent dark. The Special Interrogation Plan for Slahi that had been approved by Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld included keeping him in 24-hour darkness in a cell that was covered with a tarp so that he couldn’t even make eye contact with guards when he was fed.1

” . . . I had no clue about time, whether it was day or night, let alone the time of day. . . . When I woke up from my semi-coma, I tried to make out the difference between day and night. In fact it was a relatively easy job: I used to look down the toilet, and when the drain was very bright to lightish dark, that was the daytime in my life. I succeeded in illegally stealing some prayers, but ————————— busted me.” (265)

Pause here. Consider what it means to look down a toilet drain in order to experience a hint of the ordering rhythm of daylight, and thus a reference point for the ordering rhythm of prayer. This is not only an ingenious survival tactic, but the central image of the book.

In the midst of darkness, fear, and foulness, Slahi finds the suggestion of light—and responds to it. Slahi’s attempt to separate night from day and to pray accordingly invites us to a kind of sorrow that enables us to see what the intense governmental censorship of words and images from Guantánamo tries to obscure: the astonishing divinity of human dignity. Describing a period when he experienced auditory hallucinations and decided to agree to confess to anything the interrogators wanted him to confess, Slahi writes:

I couldn’t find a way on my own. At that moment I didn’t know if it was day or night, but I assumed it was night because the toilet drain was rather dark. I gathered my strength, guessed the Kibla, kneeled, and started to pray to God. “Please guide me. I know not what to do. I am surrounded by merciless wolves, who fear not thee.” When I was praying I burst into tears, though I suppressed my voice lest the guards hear me. You know there are always serious prayers and lazy prayers. My experience has taught me that God always responds to your serious prayers. (273)

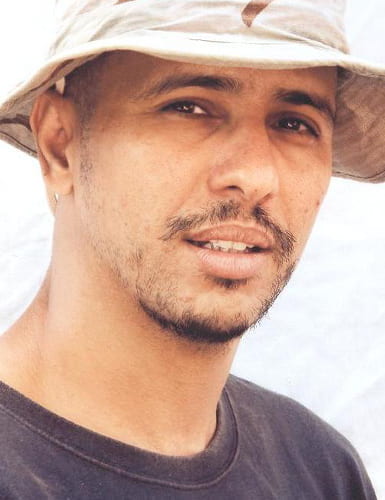

The ICRC took this photo at the Guantanamo Bay detention camp in Cuba. They gave it to Salahi’s brother, who passed it on to Salahi’s lawyer. International Committee of the Red Cross. CC BY-SA 3.0.

Slahi’s spirit illuminates his narrative. He is a hafiz: before his confinement he had committed the entire Qur’an to memory and sometimes led prayers at local mosques. The Diary was written in English, his fourth language, largely attained in detention, for an American audience, which he at times directly addresses. Slahi may have picked up the Elizabethan formality he uses to re-create his prayer in English when he read the King James Bible while imprisoned. This act of translation emphasizes his intention to convey a recognizable religious orientation to the Americans he knows may find his religion foreign and heretical. In the midst of mind-shattering desperation, the reverence Slahi reveals in this vulnerable prayer shows us what faith makes possible.

The Diary traces Slahi’s arrest in his native Mauritania, rendition to a prison in Jordan, then to Bagram Air Base in Afghanistan, then to Guantánamo, where he was subjected to a program, approved by Rumsfeld, of quasi-scientific brutality known as “enhanced interrogation.” Slahi had first become known to American authorities during the investigation of the Millennium Plot on Los Angeles International Airport in 2000, because he had gone to the same Toronto mosque as the suspect. When 9/11 happened, he was already, in a sense, on speed dial. When he turned himself in for questioning in his hometown of Nouakchott, Mauritania, he was secretly transferred to Jordan, Afghanistan, and then Guantánamo.

Of the 780 detainees ultimately held at Guantánamo, Slahi was one of a handful subjected to a “Special Interrogation Plan.” Having won a scholarship to a German university to study engineering, and possessing a gift for language and wit, the thirty-two-year-old Slahi stood out: there were so many men obviously incapable of serving an international terrorist conspiracy that the military’s overseer of the interrogation program complained that the camp was full of “Mickey Mouse” detainees.2 For the most part, the “high value” captives were being tortured by the CIA in “black sites” scattered across the world. Slahi became collateral damage in a multi-government-agency contest to see who could squeeze blood from a stone.

Slahi’s ability to compassionately illustrate the human cost of indefinite detention and the demonization of Islam on the rank-and-file of the “War on Terror” is nothing less than miraculous. His capacity for compassionate curiosity darts through the record of atrocity like a golden thread.

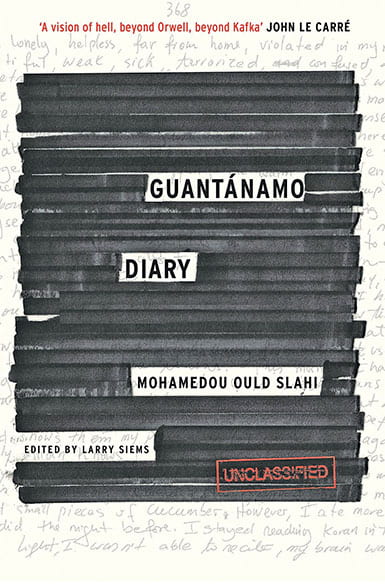

The Diary was originally written in 2005 but was not published for a decade. It now appears with the heavy redactions inserted by several government agencies: sometimes entire pages are blacked out. Apart from a collection of a few poems,3 the Diary is the first volume of detainee writing to have escaped “the wire,” as the perimeter of the detention facility is known. Though the story has escaped, its writer has not. Slahi is still detained in Guantánamo, thirteen years after his initial arrest, despite having never been charged. The initial suspicions about him proved insubstantial and the U.S. government has been unable to find sufficient evidence to charge him with any crime. He was cleared for release in 2010; appeals of that decision have held him in permanent limbo.

Slahi’s ability to compassionately illustrate the human cost of indefinite detention and the demonization of Islam on the rank-and-file of the “War on Terror” is nothing less than miraculous. His capacity for compassionate curiosity darts through the record of atrocity like a golden thread. “I would like to believe the majority of Americans want to see Justice done, and they are not interested in financing the detention of innocent people,” Slahi writes:

I know there is a small extremist minority that believes that everybody in this Cuban prison is evil, and that we are treated better than we deserve. But this opinion has no basis but ignorance. I am amazed that somebody can build such an incriminating opinion about people he or she doesn’t even know. (372)

Despite the best efforts of the full force of Washington’s legal, political, bureaucratic, and national security mechanisms, out of the prison has escaped a testament to the possibility of something recognizably human dwelling and surviving, even shining, in the prison human rights attorneys have called a “legal black hole” since 2002.4

One of the odd things about Guantánamo is how few images are publicly available. After thirteen years, there have only been a few press tours “behind the wire.” For the most part, articles about it rotate through the same handful of photographs of detainees: men dressed in orange jumpsuits and shackled in kneeling positions that suggest fear, subservience, and—I think this is key—possibly prayer. What distinguishes a “detainee” from a “prisoner” is, of course, due process: charges, a trial, and a conviction. But it is the detainees’ Islam that most marks them as “terrorists” in the public imagination. An image of hooded detainees, freshly confined in Guantánamo cages, shows men with shackled hands bent at an awkward angle, as if suspended between kneeling and prostration, as if they had been apprehended in the midst of Islamic daily prayers.

The images seem to suggest the inevitable success of a swaggering American dominance over both Islam and terror. That shaky bravado defined the early years of the War on Terror. Talk to anyone who was a high-ranking military, Pentagon, or White House official in the aftermath of 9/11, and you will be told about the intense fear that another attack was imminent, and about the pressure to ensure that attack didn’t happen. The most honest among them will talk, too, about the desire for vengeance that characterized the emotional climate of the decision makers in those first months and years. That climate of vengeance shaped behavior down to the lowest ranks. “The message from top officials was clear,” said Senator Carl Levin, who chaired the Senate’s subsequent investigation into detainee abuses; “it was acceptable to use degrading and abusive techniques against detainees.”5 Which is exactly what happened.

Most of the facts about Slahi’s detention and interrogation have been publicly available since 2009, when the Senate Armed Services Committee report on the treatment of detainees was released. That 263-page document includes three pages just listing the acronyms used throughout. The report is thin on description, and its prose matches the militarized clinical tone of the military documents it quotes:

——————– The GTMO plan stated that, while in the interrogation room at Camp Echo, Slahi would sit in a basic chair and “be shackled to the floor and left in the room for up to four hours while sound is playing continually.” His time in the room was intended to “disorient him and establish fear of the unknown” and emphasize to Slahi that ” ‘the rules have changed’ and nobody knows he is there.” The practice of shackling him to the floor and subjecting him to loud music was to be repeated over several days, interrupted by actual interrogations. Slahi was to be permitted four hours of sleep every sixteen hours.6

Slahi describes what the report doesn’t: the feeling and atmosphere that accompanied these actions, such as the extremely painful practice known as “short shackling”:

“Stand up! Guards! If you don’t stand up, it’ll be ugly!” ———– said. And before the torture squad entered the room I stood up, with my back bent because —————————————— didn’t allow me to stand up straight. I had to suffer every-inch-of-my-body pain the rest of the day. . . .

“If you want to go to the bathroom, ask politely to use the restroom, say ‘Please, may I?’ Otherwise, do it in your pants,” ———– said.

Before lunch ——————————dedicated the time to speaking ill about my family, and describing my wife with the worst adjective you can imagine. For the sake of my family, I dismiss their degrading quotations. . . .

That afternoon was dedicated to sexual molestation.– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – . . . .(224–225)

Slahi’s Diary makes torture, and the tortured language of state euphemism, into something comprehensible. When Slahi tells his story, intentionally obscurantist phrases like “extraordinary rendition” and “enhanced interrogation techniques” are given a reality that bears flesh. Early in his journey, Slahi describes being hooded, shackled, and tied to other detainees with a rope that cut into his arm. “Although I was physically hurt, I was solaced when I felt the warmth of another human being in front of me suffering the same. The solace increased when —————— was thrown over my back” (25). Whether it was chance, gift, or piety, Slahi was able to draw peace and consolation from a communal sense of compassion. Even as he is in the midst of great pain, what he finds noteworthy is his closeness to others. Through his forthright, yet understated, style, Slahi has written a speakable account of unspeakable torture. Even the scenes of the most violent beatings are rendered on the page with a matter-of-fact detachment that signals the immensity of the trauma left undescribed.

The long process from writing to declassification and, finally, to publication sheds some light on the administrative limbo that defines life in Guantánamo. After the 2005 Detainee Treatment Act passed and the worst of the vengeance-as-policy was over, Slahi was allowed paper and pen—and access to lawyers. During 2005, Slahi began to give his lawyers pieces of the manuscript that would become Guantánamo Diary. For the next seven years, his lawyers fought to have the manuscript declassified. Meanwhile, Slahi remained detained and segregated from the general population, but now allowed to garden, watch videos, occasionally Skype with his family, and wait for his habeas corpus petition to be heard. That took four years. In March 2010, a federal judge granted the petition and ordered him released. The Obama administration then filed an appeal to halt it. Despite recent pressure, there is still no hearing scheduled. In 2012, Slahi’s lawyers were finally successful in liberating his manuscript, though what they received was heavily blacked out with redactions. They passed the manuscript on to editor Larry Siems, author of The Torture Report, an edited volume drawn from the trove of documents won by the ACLU.7 The resulting book preserves the heavy black redactions left by multiple rounds of censorship. Beneath the blacked-out lines and paragraphs, Siems’s footnotes piece together something like a record of attestations drawn from Senate reports and transcripts of administrative hearings that provide context and sometimes the likely content of what has been censored.8

Guantanamo Diary

Because all names are redacted, it can be difficult to know which interrogator or guard is saying what. All female pronouns are blacked out (perhaps to elide the presence of female interrogators who had been ordered to sexually molest Slahi), while “he and his appear unredacted,” Siems explains in an early footnote (8n). In another, Siems corroborates Slahi’s estimate of arriving at Guantánamo in a group of thirty-four blind-goggled detainees with the height and weight records of thirty-five detainees processed into the camp on August 5, 2002 (25n). If there is anything fictional in Slahi’s account, it has nothing to do with his interrogations or torture. Those are all well documented in the government sources that Siems cross-references in the notes.

Finally published in January 2015, the Diary chronicles one detainee’s “endless world tour” (256) of America’s rendition and detention program, and offers a deeply humane narrative of what happens when a nation operates a secret torture program while calling itself a democracy. Publication came on the heels of the 2014 release of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence’s study—or at least the executive summary—of the CIA’s torture program and its evasion of congressional oversight. As journalists raced to find new and scandalous tidbits previously undisclosed, one Kentucky representative, John Yarmuth, bitterly exclaimed via press release, “We are better than this—America doesn’t condone torture or hide from the truth.”9

Except when it does. Except when we do.

Slahi’s narrative proceeds in a voice that is well described by one reviewer as “curiously undamaged.”10 Perhaps the power of that voice, rather than what lies behind the black bars, is what the censors most feared. “Human beings naturally hate to torture other human beings,” Slahi declares, “and Americans are no different” (370). The pages themselves become battle maps in a war to keep this inimitable voice from leaping off the page and into the world of bodies and breath; the black lines mark the advances and retreats of an empire across the terrain of a human soul.

There is something at work in the Diary that is much grander, and also quieter, than the score settling of a mere exposé. Although what Slahi describes is unquestionably brutal, the voyeuristic pleasures of fascinated guilt are largely unavailable to the reader; Slahi’s voice and vision are too robust to permit him to be reduced to his suffering. Perhaps the largely unrepresented world inside Guantánamo works in his favor: whereas the unrecognizable detainees of the orange jumpsuit photos literally cannot see because they are hooded, Slahi both sees and speaks. Everyone who appears is morally complex, caught in the crosscurrents of violence and dehumanization. Slahi’s Diary is a portrait, not of his own suffering, nor of individual villains or banal bureaucrats, but of the inherent human dignity that evades the prisons of an enormous war whose frontlines are drawn in religious terms.

“The law of war is harsh. If there’s anything good at all in a war, it’s that it brings the best and the worst out of people: some people try to use the lawlessness to hurt others, and some try to reduce the suffering to the minimum,” Slahi writes (46–47). From this stance of openhearted reflection, he offers his readers cultural signposts, trying to accommodate what he has observed about American knowledge, or the stunning lack thereof, of foreign cultures. “Tea is a crucial part of the diet of people from warmer regions,” Slahi explains. “It sounds contradictory but it is true” (41). At other times he reflects: “It’s very funny how false the picture is that western people have about Arabs: savage, violent, insensitive, and cold-hearted. I can tell you with confidence,” he assures the reader, “that Arabs are peaceful, sensitive, civilized, and big lovers, among other qualities” (359).

Slahi has thought deeply about the Christianity he encounters in his conversations with American prison guards and interrogators: “I had studied the Bible in the Jordanian prison; I asked for a copy, and they offered me one. It was very helpful in understanding Western societies, even though many of them deny being influenced by religious scriptures” (13). He has studied and debated the Christian Bible while physically shackled, beaten, held in complete darkness, and subjected to violent, sometimes sexually abusive, interrogation.

Some of the most humane and intriguing passages of the Diary are the recollected dialogues that give remarkably nuanced portraits of American Christians trying to reconcile what they had been told about Muslims with the men they spent so much time guarding. At various points Slahi mentions guards trying to convert him; he takes the opportunity for largely illicit conversation to learn more of the language and culture of the Americans holding him. The scene in which Slahi tries to get a female Christian guard who likes to talk religion with him to explain the Trinity to him is gentle, clever, and subtly hilarious:

“—————–, I really don’t understand the Trinity doctrine. The more I look into it, the more I get confused.”

“We have the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, three things that represent the Being God.”

“Hold on! Break it down for me. God is the father of Christ, isn’t he?”

“Yes!”

“Biological Father?” I asked.

“No.”

“Then why do you call him Father? I mean if you’re saying that God is our father in the sense that he takes care of us, I have no problem with that,” I commented.

“Yes, that’s correct,” —— said.

“So there is no point in calling Jesus ‘the Son of God.’ “

“But he said so in the Bible,” ————– said.

“But ————–, I don’t believe in the 100 percent accuracy of the Bible.”

“Anyway, Jesus is God,” —— said.

“Oh, is Jesus God, or Son of God?”

“Both!”

“You don’t make any sense, ————–, do you?” (357–358)

Slahi counters crushing cruelty with gentle theological ribbing. His gentleness opened what appears to be a genuine relationship of exchange: “Whenever we had time, we discussed religion and took out the Bible and the Koran to show each other what the Books say” (356).

At other times, the book provides a chilling revelation of how thoroughly Islam itself has been conflated with criminality among the military personnel Slahi most frequently interacts with. At one point, the interrogator exploits this: ” ‘In the eyes of Americans, you’re doomed. Just looking at you in an orange suit, chains, and being Muslim and Arabic is enough to convict you, —————————– said” (220).

During another interrogation, a particularly vicious interrogator repeatedly kicked and taunted him: ” ‘Uh . . . Uh . . . ALLAH . . . ALLAH . . . I told you not to fuck with us, didn’t I?’ said Mr. X, mimicking me” (255). Elsewhere, prayer and terrorism are fused in the fury of an interrogator: ” ‘Stop praying, Motherfucker, you’re killing people,’ ——— said, and punched me hard on my mouth” (252). Slahi comprehends the larger dynamics perfectly well: “[T]he war against the Islamic religion was more than obvious,” he says. Any detectable sign of prayer was forbidden: guards were instructed to stop him, with violence if necessary, any time they caught him praying:

“He’s praying!” —————————–. “Come on!” They put on their masks. “Stop praying.” I don’t recall whether I finished my prayer sitting, or if I finished at all. As a punishment ————————- forbade me to use the bathroom for some time. (265)

“I’m going to hell because I forbade you to pray,” one guard tells Slahi (334). The confession is typical of the exchanges Slahi has with guards. When Slahi asks him why he physically prevented him from praying, the guard explains that if he didn’t obey the order, “they would have given me some shitty job” (333). One has to wonder—and shudder—at what constitutes a “shitty” job if violently preventing someone from praying is a step up from that.

Through his descriptions of guards, interrogators, and the things they did to him, Slahi shows us who we really are. He does not condemn us; our own shocking sense of recognition does.

Slahi even renders visible what has largely been missing from the debates about torture and Guantánamo: the harm done to those asked to carry out sinister violence. “We make [the guards and interrogators] carry the moral weight for the rest of us,” editor Larry Siems told a lunch meeting at the Harvard Kennedy School in April 2015. At a time when the military is increasingly segregated from civilians in American society, Slahi’s ability to illustrate the human cost of a torture program on the low-ranking personnel who carry out orders from Washington is a powerful gift.11 Through his descriptions of guards, interrogators, and the things they did to him, Slahi shows us who we really are. He does not condemn us; our own shocking sense of recognition does.

Not until President Obama admitted last summer that “we tortured some folks” had there been an official acknowledgment of torture. Slahi’s narrative shocks us not because it’s new, but because we, like Yarmuth, need to believe that we are indeed “better than that.” But Slahi knows exactly who we are, and what Americans do, because he has experienced us: “We’re gonna feed you up your ass,” one guard threatens (231). And yet: in Slahi’s Diary we find something beautiful, humane, and alive, exactly in the place it shouldn’t be. While reading the Diary, I began to wonder if Slahi has written a kind of gospel for our era of indefinite detention and secret prisons. Slahi’s narrative is plain and unflinching in revealing what American cruelty does to its victims. And yet, Slahi is improbably, inconceivably still alive, morally vibrant, observant, even curious.

I am conscious of my potential critics here, who will be rightfully suspicious of the cheap typologizing of any tortured person as a Christ figure, or who would find fault with a hegemonic, Christocentric erasure of religious difference. But I take my cues from the form and content of Slahi’s narrative. I recognize the essential literary structure of the Christian gospel in the Diary‘s two-step stumble: the shocking reflection of who we really are, and the simultaneous and yet. Slahi’s “serious prayers,” offered by the dim light of a toilet drain, inspire my own. I recognize a kind of faith I dearly desire as a Christian in the depth and litheness of Slahi’s Islam. It’s the faith I want to teach. So I teach this book. It strikes me as good news.

Whether something is literally or canonically a gospel is a less urgent question to me than the question of its effect on readers. One striking cultural phenomenon marking the response to Guantánamo Diary is the seemingly reflexive urge to read it aloud, preferably with groups of people. Shortly after the book’s January 2015 release, PEN America hosted a reading in a snowbound downtown Manhattan theater in which a cast of New York actors, activists, artists, and writers read out passages. At Northwestern University, political science professor Ian Hurd organized an all-day reading of the book. The event lasted nine hours.12 In a joint project of The Guardian and UK publisher Canongate Books, the book’s website (Guantanamo diary.com) features over a dozen audio tracks of actors’ readings of the book, among them Benedict Cumberbatch, Jude Law, and even Nadya Tolokonnikova of punk band Pussy Riot, who was herself imprisoned in Russia for a year.

When I have hosted reflection groups on the book, including one at Harvard Divinity School, I have been surprised by the somewhat uncomfortable silence that precedes a volunteer’s reading of a passage. It is as if the torture has a contagious quality that threatens to steal our own voices as well. To bring Slahi’s words into one’s own body and breath requires a surprising, unusual courage; the voices that emerge are often tinged with a solemnity unmistakable to me as liturgical.

Solemnity is appropriate. I remind people that psychologists of torture have long known that it takes so very little to mangle a human being into doing anything to make pain and madness stop. The combination of isolation and sensory deprivation is, by itself, enough to make some people begin hallucinating within hours. Slahi began hearing the voices of his family. His hallucinations even worried the interrogators.13 When book group participants come into the room knowing that the topic is torture, some seem stiff, as if they’re bracing themselves. Then they discover that Slahi is empathetic, articulate, and often funny. Collectively breathing Slahi’s own voice into the room seems to restore his American readers’ sense of civic dignity and human obligation. Rather than spending a few minutes on guilty gestures of sympathy, the act of voicing Slahi’s words invites us to remember we are capable of creating a nation that is in fact “better than this.”

Slahi is able to offer the story of his suffering in a way that reveals to the world who Americans really are, and yet he invites us to imagine being otherwise. His vision for the world that could be, appended as an “author’s note” at the end of the book, is full of calm grace and improbable, yet compelling, hope.

The good news of Guantánamo is, of course, Mohamedou Slahi himself: that he has so far survived; that he has been able to withstand the grinding absurdity of his arbitrary detention with his curiosity, mind, and faith largely intact. His gift to us in the Diary is, ultimately, an opportunity for national repentance. Free him and the others held without charge; close the secret prisons. His editor believes Slahi’s Diary ought to be enough to convince us to do so. “I believe there will be a homecoming,” Siems writes in his introduction (xlix).

Slahi is able to offer the story of his suffering in a way that reveals to the world who Americans really are, and yet he invites us to imagine being otherwise. His vision for the world that could be, appended as an “author’s note” at the end of the book, is full of calm grace and improbable, yet compelling, hope:

In a recent conversation with one of his lawyers, Mohamedou said that he holds no grudge against any of the people he mentions in this book, that he appeals to them to read it and correct it if they think it contains any errors, and that he dreams to one day sit with all of them around a cup of tea, after having learned so much from one another. (373)

Slahi’s testament ends the way good news often does: with a vision of a reconciled world and an invitation to act. As I long for that cup of tea, and all that it would mean, I catch myself praying.

Notes:

- Senate Armed Services Committee Inquiry into the Treatment of Detainees in U.S. Custody (SASC), November 20, 2008, 140.

- Joseph Margulies, Guantánamo and the Abuse of Presidential Power (Simon & Schuster, 2006), 65.

- Marc Falkoff and Flagg Miller, Poems from Guantánamo: The Detainees Speak (University of Iowa Press, 2007).

- See, for instance, George P. Fletcher, “Black Hole in Guantánamo Bay,” Journal of International Criminal Justice 2, no. 1 (2004): 121–132. The phrase originated with attorney Joseph Margulies. Henry Weinstein, “Prisoners May Face ‘Legal Black Hole,’ ” Los Angeles Times, December 1, 2002.

- Council on Foreign Relations website, cfr.org/human-rights/senate-armed-services-committee-inquiry-into-treatment-detainees-us-custody/p18024.

- SASC, 137.

- Larry Siems, The Torture Report: What the Documents Say about America’s Post-9/11 Torture Program (OR Books, 2011).

- The November 2008 Senate Armed Services Committee report is widely available online and can be accessed here: www.armed-services.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Detainee-Report-Final_April-22-2009.pdf. Increasingly, newspapers are in the business of hosting digital archives for the declassified documents they have to fight to obtain. The Washington Post has a copy of Slahi’s Administrative Review Board hearings, available at media.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/world/documents/transcript_slahi.pdf.

- John Yarmuth, “Statement on Senate Intelligence Committee Report on CIA Interrogation Methods,” which can be found at yarmuth.house.gov.

- Ian Cobain, “Guantánamo Diarist Mohamedou Ould Slahi: Chronicler of Fear, Not Despair,” The Guardian, January 16, 2015.

- A 2012 Pew study showed that the military is drawing from fewer families and geographic regions and that those enlisted are living on fewer bases, resulting in a sort of cultural segregation. David Zucchino and David S. Cloud, “U.S. Military and Civilians Are Increasingly Divided,” Los Angeles Times, May 25, 2015.

- Hurd’s website offers a “how to host a public event on Guantanamo Diary” section, faculty.wcas.northwestern.edu/~ihu355/Ian_Hurd/Guantanamo.html.

- See footnote on p. 272 citing SASC, 140–41.

Marisa Egerstrom is a third-year master of divinity student at Harvard Divinity School and a candidate for priesthood in the Episcopal Church. She is concurrently finishing her dissertation in American sudies on the development of the American torture program.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.