Featured

The Fog of Religious Conflict

Eleven reflections from a conflict zone

Photo by David N. Hempton

By David N. Hempton

Religious ideas have the fate of melodies, which, once afloat in the world, are taken up by all sorts of instruments, some of them woefully coarse, feeble, or out of tune, until people are in danger of crying out that the melody itself is detestable.

—George Eliot, “Janet’s Repentance,” Scenes of Clerical LifeBoth sides [theists and secularists] need a good dose of humility, that is, realism. If the encounter between faith and humanism is carried through in this spirit, we find that both sides are fragilized; and the issue is rather reshaped in a new form: not who has the final decisive argument in its armory—must Christianity crush human flourishing? must unbelief degrade human life? Rather, it appears as a matter of who can respond most profoundly and convincingly to what are ultimately commonly felt dilemmas.

—Charles Taylor, A Secular Age[1]

I don’t know how much attention you pay to the coverage of religion offered by some of our leading newspapers and magazines, or in some of the blockbusting academic books that seek a much wider audience than would be reflected in, say, my own royalty accounts. In a quite probably misguided bout of new decanal enthusiasm, I have been reading more of this stuff than I have been accustomed to. In this admittedly limited sample of last summer’s reading, I have found that most of the material can be grouped under three categories.

The first is reporting on the seemingly endless supply of bad-news stories about religious and ethnic conflicts throughout the world. We have had reports on conflicts between Sunni and Shi’ite Muslims in East Java, between radical and more moderate Muslims in the central Russian republic of Tatarstan, between Islamists and their opponents in Mali, between Christians and Muslims in central Nigeria, between Protestant and Catholic rioters in North Belfast—quite apart from the religious dimensions of the more widely reported conflicts in Syria and Gaza. Did you know that, according to a New York Times feature on the World Health Organization, the disease that robs the most adults of the most years of productive life is not AIDS or heart disease or cancer, but depression, and that depression is particularly rife in the world’s ubiquitous conflict zones?

A second category of recent reporting on religion focuses on religious good-news stories, which are mostly a bit quirky, but sometimes also quite endearing. For example, did you know that, again according to The New York Times, there is “a wave of spirituality that is surging through the world of classical music”? Music festivals from the depths of secular Europe to major American cities are this year putting on celebrations of sacred or spiritual music. According to this report, quite hard-nosed festival directors from Salzburg to New York are convinced that people are looking for something beyond mere rationalism, or the bottom line, or more cyberspace toys. They want something with heart, meaning, emotion, and connection. Above all, they want something live and capable of touching our deepest yearnings and emotions. Even the sports pages have gone spiritual. Before the Olympics, The New York Times ran a lengthy feature on Ryan Hall, the American marathon runner, whose training for the Olympics was apparently influenced by his charismatic evangelical Christian faith. From sabbatarian training rhythms to rubbing his legs with anointed oil, and from the trinitarian spacing of his most arduous workouts to searching out obscure biblical verses that give him an endurance edge, Hall is a deadly serious Christian. So serious that when asked on a standard drug-testing form to name his coach, Hall wrote: God. When the doping official told him that he had to name a real person, Hall replied that God is a real person. Alas, this story did not have a happy ending; after eleven miles, Hall dropped out of the Olympic marathon with hamstring problems.

A third category of reporting focuses on the apparently endless feuds between conservatives and liberals in many of the world’s great religious traditions. I have read op-ed pieces eviscerating the Catholic hierarchy over its treatment of nuns and cases of sexual abuse; there are endless articles on the alleged stupidity of the Christian right in its approach to science, economics, and culture, and on its penchant for supporting ultraconservative political candidates. Conversely, there are columns by religious conservatives on the inexorable declining popularity of all forms of liberal Christianity, which in their view has become virtually indistinguishable from purely secular liberalism. The main message from the media seems to be that conservative forms of religiosity are vibrant and popular, but narrow and unacceptable, while liberal forms of religion are positive and progressive, but somehow elitist and unpopular. Hardly a great choice!

Photo by David N. Hempton

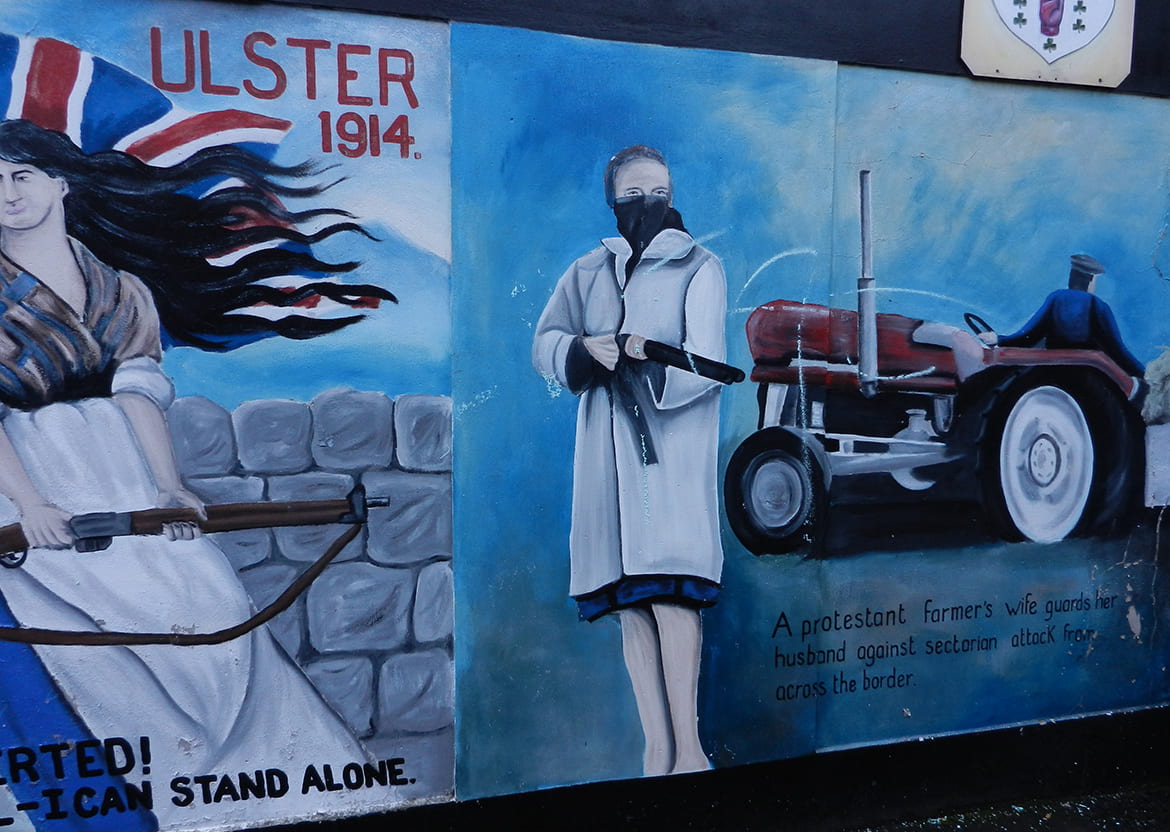

It is the first of these three categories—religious and ethnic conflicts—that I want to address, but on the way I hope also to say something about the other two. As is the way with professors with a specialism in the evangelical tradition, part of what I have to say is really a word of testimony. I was born into a Protestant working-class family in East Belfast in the 1950s and was the first in my family line to trot off to the local university, Queen’s University Belfast, in 1970. I went up to university to study English literature (Seamus Heaney was then a young lecturer in the English department), but soon converted to history. Over the course of my four-year degree, more than a thousand people were killed in what came to be known as “the Troubles,” among the worst four years of violence during the entire thirty-year conflict, which ran from the late 1960s to the late 1990s. My almost surreal memories of those years are of city-center bombs, tit-for-tat revenge killings, young men with masks and automatic weapons in their ubiquitous paramilitary organizations, highly emotional university meetings (as in the one on the Monday after Bloody Sunday), armed soldiers and armored cars patrolling the streets, and a seemingly endless succession of funerals through wet and grey urban landscapes or deep-green, melancholic country lanes. The funerals were the worst. The endless cycle of raw grief seemed to symbolize the sheer pointlessness of it all. Seamus Heaney’s poem, The Cure at Troy, poignantly captures the reality that human grief is equally painful on one side or the other: “A hunger-striker’s father / Stands in the graveyard dumb. / The police widow in veils / Faints at the funeral home.”[2]

During my student years, I naïvely thought we were witnessing the last of the world’s religious/ethnic conflicts, a kind of final paroxysm of the European wars of religion—the last frontier of the Protestant Reformation—on an offshore island off an offshore island. But of course I was wrong. Far from being the death throes of a dying phenomenon, the conflict in Northern Ireland was part of a wider international trend that also brought destructive violence to the old Yugoslavia, the Middle East, and, as we have seen from recent news reports, to many, many other parts of the world.

Living through the Troubles in Ireland as a young adult was not the happiest experience of my life, and there were many times that I wished I was somewhere else. It was, however, a remarkably formative experience. It was an environment that demanded attention, serious thought, and critical self-reflection. To help communicate some of the fruits of that reflection, I want to borrow from Errol Morris’s famous documentary film in which U.S. secretary of defense during the Vietnam era, Robert McNamara, gave his famous eleven reflections, “The Fog of War.” Some of these reflections have become classics of foreign policy realism: “Empathize with your enemy”; “Rationality will not save us”; “Belief and seeing are often both wrong”; “Never say never”; and “You can’t change human nature.”

Here are my own eleven reflections on religious and ethnic conflict, after which I will add some direct comments on their relevance to us at Harvard and more generally. I offer these in the knowledge that every conflict is distinctive and unique in important ways, but there are also repetitive tropes.

1. Religious and ethnic conflicts are more complicated than you think, and are often more complicated than so-called experts also think. Problems do not become intractable if easy solutions are available. Religious conflicts often arise from a large number of interconnecting causalities: ownership of land and territory; ancient settlement patterns; competing religious and/or ethnic identities; differential access to economic or social power; existence of long-standing grievances reinforced by emotive symbols, rituals, celebrations, and memories; residential and cultural separations; selective access to different information streams; competing nationalisms and political aspirations; differential senses of divine empowerment; highly selective readings of history; and so on. Beware of monocausal explanations or universalizing theoretical or ideological constructions. Beware also of the condescension of outsiders, who only half know what it is like to live in conflict zones.

In Northern Ireland old colonial settlement patterns that separated Protestants and Catholics generated different religious and cultural systems and, ultimately, competing nationalisms by the end of the nineteenth century. Crudely speaking, one side saw themselves as Protestant and British, the other as Catholic and Irish. One side had most of the political and economic power; the other was discriminated against and felt alienated. One community was a minority in Northern Ireland; the other was a minority on the island of Ireland. The insecurities caused by double minorities and double majorities, depending on the geographic selection of each side, helped create the vortex of conflict in Northern Ireland.

2. Religious and ethnic stereotyping are powerful agents in sustaining ethnic and religious conflicts. Demonizing the other is the first important step in rendering them deserving of attack or elimination. Most stereotyping of the other has some basis in observable facts and behaviors, otherwise the stereotypes would not exist in the first place, but they are always horribly distorted to suit the prejudices of one side or the other. This is perhaps the most dangerous human trait in our world and needs to be confronted with relentless vigor. In Northern Ireland, Protestants thought Roman Catholics were enslaved to their church, prone to having large families, feckless when it came to work, and deeply subversive of the state. Roman Catholics saw Protestants as stiff-necked colonists, eager for dominance, discriminatory in their exercise of power, and humorless in their cultural expressions. Both sets of stereotypes had just enough truth in them to make them work, but not enough for either side to understand the complex dynamics that sustained them.

3. Violence radicalizes people. Violence is often triggered by the crossing of symbolic or real boundaries and generates a momentum of its own. One side generally has more access to state instruments of power, the other resorts to “terrorism.” Deaths and funerals stoke the emotional intensity and set up demands for revenge. Once conflicts start, no one knows when and how they will develop. Things may seem bad in conflict zones, but you always know they can get a whole lot worse. Think of Srebrenica, Tripoli, Aleppo, Jos, Timbuktu, Belfast, Beirut. Part of the trauma of living in conflict zones is never being quite sure how bad it can get. As a person living in Belfast, I came to believe that violence is a terrible solution to human conflicts, but the historian in me came to see that, sometimes in human affairs, postponing conflict, as in appeasement before World War II, only increases the cost of human misery in the long run.

4. Religious and ethnic conflicts put enormous pressure on the law and legal processes. Religious traditions often have different histories of legal interpretation and enforcement. Under pressure of violence, states often start shifting the balance between state security and individual rights (special courts, internment without trial, use of informants). Much of this ends badly and makes the situation worse. Internment without trial had disastrous consequences in Northern Ireland and has sullied the reputation of the United States on the international stage. Moreover, different traditions have different views of how law should work. In Northern Ireland, for example, most Protestants supported the need for internment without trial and trials without juries; most Catholics opposed them. What we know from legal historians is that the world’s religious traditions have contributed massively to the evolution of legal frameworks, and that those legal frameworks, despite appearances to the contrary, are not as normative as we think, but rather, are constructions of particular times and places. In conflict zones, as in the resolution of U.S. elections, law is always contested territory.

5. Many people inside conflict zones see the conflict as a zero-sum game; few outside see it that way. To outsiders, the most perplexing feature of conflict zones is the apparent propensity of participants in conflicts to see their situation as a zero-sum game worth dying for, rather than a problem that needs resolving in the spirit of “half a loaf is better than no bread.” Naturally, the zero-sum mentality stokes violence. The stakes could not be higher. I saw a news report from Syria recently where one of the rebel combatants stated quite bluntly that he would fight to the death, because there was nothing else worth living for. People who see no options for themselves are, literally, people without options.

6. It is easy to be wise after the event. Before conflict breaks out things may seem entirely “normal”; after it breaks out, people see more clearly the structural problems that created the conflict in the first place. There is nothing inevitable about conflict, and there is nothing guaranteed about peace and stability. There is often a fragile veneer of civility in societies, which can be stripped with distressing speed and consequences. This can happen in any community, anywhere.

7. Living in conflict zones requires individuals to make moral choices on a regular basis. How one works to maintain humane values in the midst of inhumane acts is a constant struggle to define one’s humanity. Part of that involves serious evaluation and criticism of one’s own community and traditions, perhaps even of one’s own family’s traditions. This can be emotionally painful and intellectually challenging. The constant struggle for understanding and empathy for those “on the other side” is both profoundly difficult and deeply rewarding. Finding solid ground upon which to make judgments about what is happening around you is extremely difficult, not least because each side has access to different media and information streams. But peacemaking begins there.

Photo by David N. Hempton

8. Social and economic misery stokes conflict and makes peacemaking much more difficult. The reverse is also the case, especially sufficient economic opportunities for young people (particularly young men). Peacemaking needs to be backed by considerable economic resources. There are few things more dangerous in any society than the existence of large numbers of unemployed, young males angry about their own lives and eager for revenge against the alleged cause of their disaffection. Hence, a serious appreciation of the economic dimensions of conflicts and their resolution is vital. Money and development cannot solve ethnic and religious conflicts, but they sure help.

9. Leadership matters. Religious leaders at all levels have the capacity to make things better, or worse. Mid-level clerics or self-appointed demagogues who lead communities can have devastatingly bad influence on conflict zones. The appeal to sacred texts, historic traditions, and “authenticity” can set up the kind of ideological fervor that leads inexorably to violence. Fortunately, the reverse is also the case. Wise and morally courageous religious leaders can have surprisingly strong influence. Important elements of the Northern Ireland peace process were put in place by the priests of Clonard Monastery in West Belfast and by some Protestant ministers whose commitment to bridge-building sometimes alienated them from their own congregations.

10. Peacemaking is a process, not a result. Settlements can be refined over years, even decades, but beware of ongoing dynamics that are making the problems even worse. In Northern Ireland important contributions to peacemaking were made by women’s groups, by those who maintained professional standards in law, education, and medicine, by religious groups who brokered reconciliation, by creative artists who built cultural bridges, and by groups of concerned citizens who came together for shared purposes (for example, disability and housing groups). Everyone can have a stake and a role. Everyone counts, either positively or negatively.

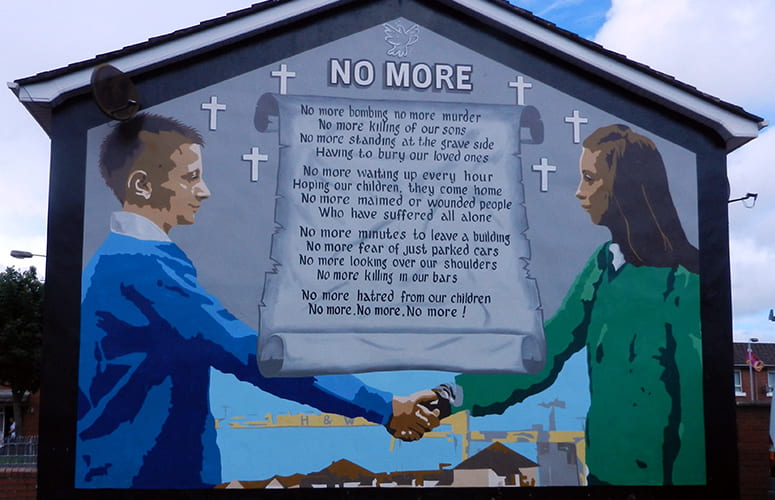

11. History makes you pessimistic; but very occasionally, the human desire for peace and justice surprises you. Heaney writes in The Cure at Troy, “History says, Don’t hope / On this side of the grave. / But then, once in a lifetime / The longed-for tidal wave / Of justice can rise up, / And hope and history rhyme.” One of the most perplexing issues I struggled with in Ireland is that a combination of a pessimistic temperament and a deep historical training in the roots of the Irish conflict made me congenitally skeptical, even cynical, about any possible way out of the conflict that did not represent the ultimate victory of one side over the other. In dark moments, I also thought it was a zero-sum game. Things are still far from perfectly settled in Northern Ireland. Residential segregation is unacceptably high; the educational system is still divided; structural discriminations still exist; the peace wall in Belfast is still standing; periodic bouts of rioting still take place; some paramilitary organizations still mount bombings and shootings; and the economy lags in tandem with most of the rest of Europe. But if you had told me in the 1970s that one day a power-sharing administration would emerge in Northern Ireland, with the Protestant fundamentalist preacher, Ian Paisley, as first minister, and the one-time member of the Provisional IRA, Martin McGuinness, as deputy first minister, I would have questioned your sanity. Things are better, but far from perfect.

This past summer I toured many of the working-class districts of Protestant and Catholic Belfast. The old divisive murals, flags, and emblems are still there, provocatively declaring ownership of territory, but there are also some new murals paying homage to concepts of social justice, the dignity of labor, community pride, and human rights. These concepts have not triumphed, but at least they are visibly there.

Photo by David N. Hempton

What use are these eleven reflections from another time and another place to Harvard Divinity School and Harvard University?

1. Be informed. Be religiously literate, not just in a forensic way of knowing more information about religious traditions, but globally engaged and morally committed. A graduate of Harvard College needs to understand: that Muslims are killing Muslims in Syria and how religion divides them; why evangelicals support Roman Catholics on right-to-life issues, but also that they see what is at stake very differently; why white evangelicals in the United States vote disproportionately Republican, while black evangelicals vote disproportionately Democrat; why women in many cultures seem more religious than men and what that may mean for social and economic aid. We at HDS, in partnership with our colleagues in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences and other schools, can help make our college graduates more religiously literate. But we’ll have to work for it, commit to it, and make it a priority of our school. It also requires courage, not just more knowledge.

2. “Only Connect.” Some of us have joint or courtesy appointments in other departments at Harvard, but all of us work across disciplines: that is the nature of religious and theological studies. And we all have colleagues, known and unknown, and partners, current or potential, in other schools and departments who can learn from us and from whom we can learn in turn. Some of us have already found partners and joint ventures with colleagues in public health, medicine, law, government, education, history, literature, political science, and so on. Can we do more to make connections with people with expertise in other areas to lay bare the full complexity of religious traditions and their social and political contexts? Harvard, with its wide range of undergraduate disciplines and graduate schools and its unparalleled library resources, is perfectly set up for this. We need to learn how to access these resources and contribute our expertise to them.

3. Don’t be condescending to those in difficult situations. We are not as good or as smart as we think we are, even at Harvard. People do not find themselves in conflict zones because they are much more wicked and stupid than we are. That, too, is a stereotype.

4. Religion is not the source of all good or all bad things in culture. Despite what some of our most influential intellectuals think, do not assume that the world would necessarily be a better place without religion altogether. I saw remarkable acts of goodness, decency, and heroism motivated by religious faith in Northern Ireland. The press rarely reports this, and academics hardly know what to do with it. It is often the day-to-day kindnesses and considerations that can help to defuse violence or open up the possibility for more creative dialogue between contending parties. We should not depend on modernity and secularization to solve religious conflicts. The tide of history is not turning in that direction after all. Religion often sanctifies and legitimizes conflict, but it is almost never the sole cause.

5. Finally, be actively engaged peacemakers at every level and in all aspects of your lives, here and in the future. Refuse to stereotype. Think creatively about how religion works in the world, and use all your talents. We are educating teachers and leaders who move on to colleges and service organizations around the country, and increasingly around the world—graduates who, in turn, educate more undergraduates and graduates, future leaders and citizens, and religious practitioners and believers. To go back to George Eliot and Charles Taylor, the world remains to be convinced that religious melodies can be played with harmonious-sounding instruments, or that we can, in Taylor’s words, respond “profoundly and convincingly to what are ultimately commonly felt dilemmas.”

I conclude with the words of Seamus Heaney, whose family tradition in Northern Ireland, as it happens, was on the other side of mine:

So hope for a great sea-change

On the far side of revenge.

Believe that a further shore

Is reachable from here.

Believe in miracles

And cures and healing wells.

David N. Hempton is Dean, Alonzo L. McDonald Family Professor of Evangelical Theological Studies, and John Lord O’Brian Professor of Divinity at Harvard Divinity School. He presented this address at the HDS Convocation on August 30, 2012, shortly after his appointment as Dean.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.