Featured

The Dialogue of Socialism

Common interest in a better world led the way for religious pluralism.

Courtesy Andover-Harvard Theological Library

By Dan McKanan

For most churchgoing Protestants in nineteenth-century America, the name “Owen” evoked a fascinated horror. The Owens—father Robert, son Robert Dale, and their close associate Frances or “Fanny” Wright—were notorious “infidels,” preaching that the Bible was a fable, the clergy hypocritical scoundrels, and human character a product of environmental factors rather than spiritual grace. Like their freethinking predecessor Thomas Paine, they were foreigners: Robert Senior visited the United States briefly in 1825, leaving Robert Dale Owen and Fanny Wright behind to promote his ideas in the New World. Above all, they were social radicals. Wright was notorious for her feminist sentiments and for the interracial commune she established at Nashoba, Tennessee. Robert Owen espoused a pure communism in which all property would be shared equally and a common system of childrearing would prepare everyone for a culture of equality. His purpose in coming to the United States was to establish such a society at New Harmony, Indiana; when that community formally dissolved after a tempestuous two years, Wright and Robert Dale Owen turned their energies to a radical newspaper called the Free Enquirer and to the Working Men’s Party, which they joined in 1828 to support striking journeymen and demand universal male suffrage, free public education, and a 10-hour day.1

Yet when Robert Owen arrived in the United States, he was welcomed by a society of Bible-quoting Protestants. The New York Society for Promoting Communities was the brainchild of Quaker physician Cornelius C. Blatchly, who recruited a board that included five ministers. Among them were a Congregationalist who had recently embraced the esoteric teachings of Emanuel Swedenborg and two leaders from a rebellious Methodist Society that repudiated the authority of bishops, celebrated working-class culture, and had facilitated the emergence of the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church as a distinct denomination.2 Together, these visionaries called “every religious congregation” to reconstitute itself on the basis of the “community of goods” first practiced by the apostles. Successful communism, they argued, would necessarily be religious, because “all goodness comes only from God” and only the influence of the gospel could overcome the “inefficiency of human and external laws to reform and regulate the conduct of the social family.”3

Surprisingly, Blatchly’s Society published this millennial manifesto alongside excerpts from Owen’s writings in which he defended socialism on an opposite basis. For Owen, “the character of man is always formed for him . . . by his predecessors,” and he insisted that the economic system of joint ownership was a sure means of preventing “in the rising generation . . . the miseries which we and our forefathers have experienced.”4 The juxtaposition of these two arguments helped inaugurate more than a century of interaction that brought radical Protestants into continuous practical cooperation—and more intermittent interfaith dialogue—with disciples of Owen, Charles Fourier, and Karl Marx, as well as with a diverse mix of spiritualists, Theosophists, Reform Jews, New Thought practitioners, Ethical Culturists, and humanists who shared their vision of a post-capitalist society.5

Socialism (a term coined by Owen’s disciples, defined here to include both “utopian” experiments and more “political” organizations) is not commonly seen as a site for interfaith dialogue, for at least two reasons. First, its history does not easily mesh with the usual chronology of dialogue. Many interpreters present dialogue as an eminently twentieth-century phenomenon, possible only after American culture had moved through the stages of toleration and inclusion to a mature “pluralism.” And that has certainly been true for the majority of Americans and their churches. After the high profile encounters of the 1893 Parliament of World Religions, mainstream American Protestants reached out to the religious “other” in a series of concentric circles, committing to the Protestant ecumenism of the Federal Council of Churches in the 1910s, to the tripartite system of “Protestant-Catholic-Jew” in the 1960s, and seriously encountering Hindus, Muslims, and Buddhists only after the immigration reform of 1965 brought large numbers of Asians into professional-class neighborhoods.6 It has only been in the last decade or so that most dialogue organizations have widened the table to include people of “no faith” as well.7 Yet the socialist dialogues of the nineteenth century typically excluded orthodox Calvinists and Catholics while embracing Reform Jews, Theosophical disciples of the Buddha, and a host of movements generally perceived as “unbelieving.”

Fanny Guthrie Wright, 1795-1852. Courtesy Andover-Harvard Theological Library

This is the second reason that socialism has usually been left out of the dialogue story: it is not generally understood to be “religious” at all. There is merit in that perception. The Owenites were “secularist” in their zeal for church-state separation and “antireligious” in their tendency to spend more time criticizing Christianity than they did in spelling out their religious alternative. The same was true for doctrinaire Marxists, though less so for spiritualists, Theosophists, Ethical Culturists, New Thought adherents, and humanists, all of whom tried to place primary emphasis on what they did believe. All of these groups departed from conventional understandings of “religion” by disavowing a supernatural basis for their beliefs about ultimate reality, though they often held beliefs that seemed supernatural or irrational to outsiders. Typically, they were composed primarily of people who had once been Protestant, or at least had come from culturally Protestant families. The dialogue between members of these groups and radical Protestants thus crossed boundaries of faith but not culture, and participants on both sides shared prejudices against Roman Catholicism in particular and established or ritualistic religions in general. Many participants even changed sides, lapsing from their Protestant commitments over the course of the dialogue! It was easy to see the conversation as one between believers and apostates rather than between two distinct religious worldviews.

This perception of religious absence rather than presence obscures the fact that many ex-Christian socialists had both explicit beliefs about ultimate reality and much of the apparatus we usually associate with religion—creedal statements of belief or disbelief, “social hymns,” designated leaders (many of them originally credentialed as Protestant ministers), rituals of initiation and excommunication, even the practice of meeting on Sunday mornings for singing and a sermon. Robert Owen devoted a major section of his Book of the New Moral World to “The Principles and Practice of the Rational Religion,” and frequently claimed that observance of this religion would usher in the millennium.8 His followers gathered in such freethinking congregations as Boston’s Society of Free Enquirers and New York’s Universal Community Society of Rational Religionists. Their services featured readings from Owen’s writings, songs from his Social Hymns, and talks on topics ranging from the platform of the Working Men’s Party to the doctrine of the soul.9

Congregational institutions of this sort provided an indispensable base of support for the labor unions, political parties, and utopian colonies that are the better-remembered institutions of every wave of socialism. Without the former, the latter might not have come into existence. But practitioners of post-Christian spirituality were not alone in socialist unions, parties, and colonies. They worked alongside a roughly equal number of Protestants and (especially in the twentieth century) Jews who found a powerful sanction for socialism in biblical faith. Some of these biblical believers gathered in their own freestanding radical congregations, while others clung precariously to the fringes of mainstream denominations. On several occasions, their cooperation with post-Christian socialists blossomed into dialogue.

Robert Dale Owen and Frances Wright voiced their commitment to dialogue in the first issue of the Free Enquirer. Declaring that “silence on the subject of religion seems to us little better than treason to truth and virtue,” they promised to open their pages to “any spirited, well written communication, be it religious or infidel, orthodox or heterodox, if it be dictated by good taste and expressed in the spirit of charity.”10 Undoubtedly, this reflected their zeal for the principle of free speech more than any desire to listen deeply to their Christian brothers and sisters. Still, they set a precedent for several instances of meaningful interchange. When budding abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, who then based his critique of slavery on biblical authority, was turned away from both Unitarian and Orthodox Congregationalist pulpits in Boston, the First Society of Free Enquirers opened its hall for his revolutionary demand for immediate abolition.11 (Garrison repaid the favor a few years later by protesting the imprisonment of the Society’s “minister,” Abner Kneeland, on charges of blasphemy as “a proof of the corruption of modern Christianity.”12)

In 1835 Kneeland’s newspaper, the Boston Investigator, also featured a brief exchange with Orestes Brownson, who, like Kneeland, was a former Universalist minister who had been disfellowshipped for heterodox views; he had come to Boston to create a Society for Christian Union and Progress as a rival to Kneeland’s Free Inquirers. While Kneeland defined himself as a non-Christian “pantheist,” Brownson (at that moment in his long spiritual pilgrimage) sought a basis for Working Men’s politics in the Christian scripture. And so he wrote to Kneeland that he believed humanity could be divided into a “stationary party” that supported “things as they are” and a “movement party” that “desires something better.” Conceding that organized religion was generally aligned with the “stationary party,” he posed a question: “Suppose you should find the church maintaining the most universal freedom, exerting itself incessantly to meliorate the condition of man, carried away always by a spirit of progress, of perfectionment, would you not cease to oppose it?” Kneeland quibbled with Brownson’s categories, noting that even Roman Catholicism was notoriously un-stationary in its list of doctrines. After conceding the main point—he would not “object to the mere name of christianity, were its principles to be what you suppose I would wish to have”—Kneeland added waggishly that anyone who “avow[ed] such principles, and endeavor[ed] to carry them out in practice” would “no more be considered a christian by the ‘stationary party‘ of christians, than I am.”13

Kneeland aptly predicted the way in which dialogue would unfold in the next great wave of American socialism. Charles Fourier, whose detailed communitarian blueprint inspired dozens of colonies in the United States, appealed to many American Christians precisely because he was no Robert Owen. Neither an atheist nor an exponent of the theory that character is formed by environment, the eccentric Frenchman taught that the human person is a complex of divinely ordered “passions” (for sensory pleasure, for romantic love and parental affection, for a diversity of occupations, and above all for “universal unity”) that will harmonize perfectly with the passions of others so long as the “Divine Social Code” is followed. Apparently drawing on strands of Western esotericism, Fourier affirmed that this same code explained the gravity-like laws of “attraction” binding together individuals, groups, planets, and even universes, as well as the hidden correspondences linking the musical scale and the sequence of planets to human passions.14

Fourier’s theory of correspondence closely paralleled the esoteric Christianity of Emanuel Swedenborg, and so it naturally appealed to the Swedenborgians (among them Blatchly’s erstwhile associate) who organized the Leraysville Association and to the Transcendentalists of Brook Farm in West Roxbury, Massachusetts, many of whom were familiar with Swedenborg’s writings.15 But other phalanxes were dominated by Hicksite Quakers or the ecumenically minded Disciples of Alexander Campbell, and virtually all took a fierce pride in their religious diversity. “We had seventy-four praying Christians, including all the sects in America, except Millerites and Mormons,” claimed one phalanx leader. “We had one Catholic family (Dr. Theller’s), one Presbyterian clergyman, and one Universalist. One of our first trustees was a Quaker. We had one Atheist, several Deists, and in short a general assortment; but of Nothingarians, none; for being free for the first time in our lives, we spoke out, one and all, and found that every body did believe something.”16 The Brook Farmers took special delight in sharing their religious differences. One recalled learning to appreciate “the great beauty of the Swedenborgian doctrines” from one friend, the inner meaning of Judaism from another, and the “symbols” of Catholicism from “persons who are not and never can be Romanists any more than myself. “17 On a more humorous note, another Brook Farmer recalled how the simple task of peeling potatoes provided an occasion for a woman of working- class background to introduce “stirring Methodist hymns” to a companion who, “having stepped at a bound from Episcopacy to rationalism, was a stranger to this spirit.”18

The effect of this dialogue was both mutual understanding and a convergence toward religious liberalism. “ ‘I am a Jew, but a liberal, understanding Jew,’ ” one Brook Farmer quoted his companions. “ ‘I am a Catholic, but I am a liberalized Catholic,’ says another. ‘I am a Swedenborgian, but my belief liberates me from the crudities of Swedenborg,’ say others. . . . ‘We all see how the forms of our churches were intended for good, and we all see how many of them have been prostituted.’ ”19 The result was what Kneeland had predicted: however Fourierists understood themselves, their neighbors viewed them as rank infidels, and those phalanxes that attracted significant numbers of truly orthodox Protestants experienced wrenching divisions. Orestes Brownson, by this time a Roman Catholic who had repented of his youthful radicalism, aptly noted that the Fourierist “starting point” was “at the opposite pole from Christianity” because it denied original sin. The rich dialogue of Fourierism was for him a symptom of the “miserable eclecticism” of the age, which reduced every religion to “symbols. . .of partial truths” and thus denied the possibility of truly authoritative revelation.20

In part because most of its Christians were liberal Unitarians rather than orthodox Calvinists, Brook Farm was able to continue the practice of dialogue even after its demise as a community. In 1847 former community members and friends organized a Religious Union of Associationists that for four years gathered weekly for musical performances, prayer, and presentations on such varied topics as the “Solidarity of the Race,” “The War With Mexico,” and “The Relation of Christ and the Spiritual World to Us.” Among their many dialogues was a conversation among a Catholic, a Jew, and a rationalist about the diverse paths that had brought them to the Associationist movement.21

Though spiritualism is remembered for its spectacular manifestations of contact with dead spirits, the movement was also marked by a vigorous tradition of both feminism and socialist activism.

Fourierist communities provided an important seedbed for the most successful non-Christian religious movement in nineteenth-century America, the wave of spiritualism that swept the nation in the 1850s. (Two other milieus that fostered spiritualism were radical abolitionism, especially in upstate New York, and the Universalist denomination; both Robert Owen and Robert Dale Owen were also among the radicals who embraced spiritualism during its heyday.) Though spiritualism is best remembered for its spectacular manifestations of contact with dead spirits, the movement was also marked by an elaborate cosmology and a vigorous tradition of both feminist and socialist activism.22 Most phalanxes that survived into the 1850s hosted séances; some of those that didn’t were reborn as spiritualist communities; and several community leaders had subsequent careers as spiritualist lecturers. The best known systematizer of the movement, Andrew Jackson Davis, was notable for the degree to which his cosmology blended Swedenborgian mysticism with Fourierist social theory.23

Davis, who began his career as a medium transmitting spirit messages from Swedenborg, increasingly divorced his harmonial philosophy from Swedenborg’s Christian exegetical context. “The church estimate of human nature is an insult to the Great Spirit,” he wrote in one book, while in his own (perhaps half-serious) catechism he answered the Calvinist question about the “chief end of man” by saying that it was “endless progression; to do good, be happy, get wisdom, and aspire calmly toward perfection; to become harmonious even as his Father-God and Mother-Nature are harmonious.”24 Such rhetoric was not calculated to please socialists who felt they were following the gospel path to God’s Kingdom on earth.

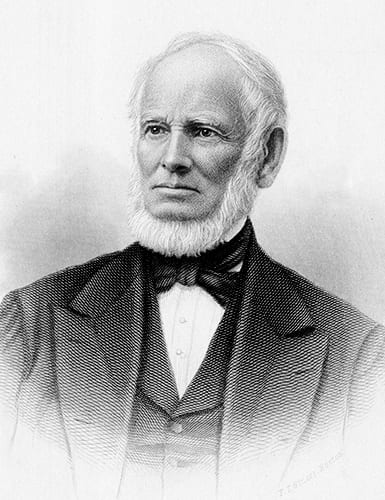

One such socialist was Adin Ballou, who had steered his Hopedale community of “Practical Christian Socialism” on a path that was parallel to but distinct from Fourierism because he regarded Fourier as both insufficiently Christian and too wedded to abstract theorizing.25 A prodigiously productive scriptural exegete who wrote the century’s most influential treatise on Christian pacifism, Ballou was predictably “amazed and confounded” by the way Davis’s writings “sweep away very unceremoniously some of our long cherished religious opinions and views.” But he also found that they “confirm some of our purest, sublimest, most unselfish convictions and aspirations.” Ballou’s sympathy for Davis’s social ideals not only kept him reading; it led him to support spiritualist experimentation at Hopedale (especially after the death of his beloved son, which gave Ballou new incentive to contact the spirits) and to chair several spiritualist conventions. The ultimate fruit of Ballou’s participation in this dialogue was a proposal for a Christian spiritualism that would allow the “fundamental truths” of Christianity to be “reaffirmed, clarified from error, demonstrated anew, and powerfully commended to the embrace of mankind by fresh spiritual communications.”26

Spiritualism was at the height of its influence when Karl Marx unveiled a radically new system of “scientific socialism.” Dismissing the schemes of both Owen and Fourier as “utopian” and rejecting all forms of religion as understandable but unhelpful “opiates,” Marx insisted (with as much faith as science!) that a class-conscious proletariat was historically destined to usher in socialism by first seizing state power and then allowing the state to wither away. This vision had little room for the vagaries of spiritualism, and yet for a brief moment the two movements might have merged in the United States. In 1871, just as Marx’s International Workingmen’s Association was trying to gain a foothold among both native-born Americans and German immigrants, a highly self-aggrandizing spiritualist named Victoria Woodhull organized section 12 of the Association. In rapid succession she managed to get both the American Association of Spiritualists and the National Woman Suffrage Association to nominate her for the presidency of the United States. Though this feat was the result of manipulation rather than genuine leadership, it also exposed the overlapping constituency of the three movements.27 Indeed, as open-minded experiments exposed spiritualism to be less “scientific” than it originally claimed, it was natural for spiritualists to drift to the (perhaps equally suspect) claims of scientific socialism. The leadership of the two movements continued to overlap into the early twentieth century, when several journals promoted both causes and at least one Socialist local (in Galena, Kansas) was chaired by a devout spiritualist.28

American socialism did not unfold according to plan because the native-born proletariat was too racially divided to be fully class-conscious and too in love with Jesus to accept dialectical materialism.

With or without spiritualist support, American socialism did not unfold according to Marx’s plan. The native-born proletariat was too racially divided to be fully class-conscious and too in love with Jesus to accept dialectical materialism. Marx’s most ardent disciples were immigrants, many with bitter memories of reactionary established churches in Europe, who dominated the Socialist Labor Party of the 1890s and the Communist Party formed in the wake of the Russian Revolution. If doctrines and excommunications make a religion, these parties were certainly religious, and the latter in particular was profoundly shaped by Yiddish culture and Talmudic styles of exegesis. But it would be a stretch to say that they were arenas for interfaith dialogue.

The situation was quite different for the milder, less class-conscious forms of socialism that sprang up in the last two decades of the nineteenth century. Appalled by the persistence of poverty amid industrial abundance, Henry George proposed in Progress and Poverty (1879) a “single tax” on land that would have effectively socialized real estate but not other forms of capital. Laurence Gronlund went a step further in The Cooperative Commonwealth (1884), arguing that collective ownership of both land and capital could be achieved through an evolutionary consolidation of existing monopolies rather than a violent revolution. This was surely a form of socialism, though when Edward Bellamy popularized it in his novel Looking Backward (1888), he cleverly labeled it as “Nationalism” to avoid anti-Marxist stigma. Each in turn, George and Bellamy inspired experimental communities and electoral politicking before folding into the broader Populist movement.29

Just as spiritualism and Fourierism were intertwined, so Bellamyite Nationalism built on the organizational structures of Theosophy, a partial successor to spiritualism that relied on the revelations of mysterious “Mahatmas” rather than of dead spirits for its cosmology. The Theosophical Society’s first objective was “to form a nucleus of a Universal Brotherhood of Humanity,” and when a cluster of Boston Theosophists discovered a similar hope in Bellamy’s novel, they procured an endorsement from the Society’s leader, Madame Blavatsky, who agreed that Bellamy had identified “the first great step” toward brotherhood. The Boston Theosophists also initiated a national network of “Nationalist Clubs” that quickly attracted Protestant ministers. Nationalist clubs ceased to be an arena for dialogue when their turn toward electoral politics gave Blavatsky cold feet. “If Nationalism is an application of Theosophy,” she urged, “it is the latter which must ever stand first in your sight.” Still, Theosophists went on to build a series of cooperative colonies in California, and Theosophical ideas became integrated into the discourse of reform-minded journals.30

Adin Ballou, 1803-1890. Courtesy Andover-Harvard Theological Library

Many of the Protestant ministers who were drawn to Nationalism had first had their social consciences pricked by the absence of working-class people in their congregations. By the turn of the twentieth century, these ministers and their lay allies had coalesced into a diverse movement that would eventually be labeled the “social gospel.” Many histories of the social gospel assume that its institutional base was in the Protestant seminaries, the denominational social service agencies, and above all the Federal Council of Churches, founded by social gospelers in 1908. These organizations included more than a few committed socialists, but they were dominated by reformers whose vision fell short of socialism. Moreover, they had little commitment to interfaith dialogue: the Federal Council, in particular, drew its boundaries narrowly enough to exclude Unitarians and Universalists, to say nothing of spiritualists and Theosophists.

A rather different set of organizations appealed to those social gospelers who believed, with labor leaders Terence Powderly and Eugene Debs, that Jesus was a class-conscious worker whose gospel required the overthrow of capitalism. Most of these activists participated in informal “fellowships” that brought ministers and laypeople together for conversation and mutual accountability. The most famous of these was the Baptist Brotherhood of the Kingdom; the most notorious was the Midwestern Kingdom movement, which helped propel its founder George Herron from the Congregationalist ministry to a bitterly anticlerical style of Marxism. Even after renouncing Christianity, Herron participated in a Chicago “Fellowship” of socialist activists who shared his hostility for organized Christianity.31 Other fellowships were intentionally interreligious. New York’s Collectivist Society, organized by an Episcopalian layman, included Baptist Leighton Williams and feminist Charlotte Perkins Gilman, whose His Religion and Hers proposed a naturalistic faith committed to the well-being of future generations rather than eternal life in heaven.32 The Brotherhood of the Daily Life, active in 1905, declared itself “Catholic in its broadest sense. Jew, Gentile, Christian or Pagan, all are welcome.”33

Another important institution for radical social gospelers was the freestanding “People’s” congregation. Though these churches had a variety of trajectories, they were most typically launched by charismatic Protestant ministers who had gotten into trouble with their denominations both for biblical liberalism and for sympathy with organized labor. Some were tiny and struggling; others attracted parishioners by the thousands and built massive edifices. Free from confessional moorings, they were able to declare social concern as their core identity. Thus, Chicago’s People’s Church, launched in 1880, promised to provide a place where “strangers and those without a religious home, and those of much or little faith” could unite in “the great law and duty of love to God and man, and in earnest efforts to do good in the world.”34 People’s Church of Cincinnati said its only “article of faith” was the “establishment of the brotherhood of man,”35 while in the 1930s the Church of the People in Seattle “made it obligatory upon applicants for membership to subscribe to the dogma that the capitalistic system is inimical to the religion of Jesus.”36

The exploration of diverse religious ideas was a formative practice at many People’s Churches. The sanctuary of People’s in Cincinnati displayed quotations by both radical Christians and freethinkers—among them Lev Tolstoy and Thomas Jefferson—alongside a single biblical admonition to “know the truth and the truth shall make ye free.” The Los Angeles Fellowship, a thousand-member congregation launched by a former revivalist who had been converted to socialism by George Herron, offered classes on Whitman, Emerson, and the Bhagavad Gita.37 And Seattle’s Church of the People encouraged dialogue between Christians and Communist Party members by welcoming both into the congregation’s fellowship. “Communist members are among the best,” reported the minister. “They have a sense of discipline that others lack. . . . One thing is certain, the Communists have learned a good deal about the religion of Jesus and the religionists have learned even more about Communism.”38

Perhaps because of these experiences of dialogue, veterans of the fellowships and the People’s Churches played a vital role in fostering religious pluralism within the most electorally successful socialist entity in United States history, the Socialist Party of America. Ostensibly Marxist in ideology, the party brought together Marxists who found the Socialist Labor Party too narrow and Populists who found William Jennings Bryan’s 1896 campaign too broad in its emphasis on “free silver” rather than the fight against capitalism. Protestant ministers had a special cachet among the party’s founders, who hoped they would attract native-born voters into an alliance with immigrant socialists who were not yet citizens. Thus, at the founding convention in 1901, George Herron served as temporary chair and a key negotiator between the factions, while a few People’s Church ministers were among the delegates. Herron worked with another former minister to establish the Rand School of Social Science (for party activists in training) in New York City; former ministers were elected to office on the party ticket in California, Montana, Wisconsin, and Massachusetts; and a Universalist pastor named Charles Vail signed on as the party’s first “national organizer.”39

Most of these ministers were active in the Christian Socialist Fellowship (CSF), which, despite its name, created ample space for interfaith dialogue. Founder E. E. Carr believed (in accord with the Socialist Party’s electoral strategy) that “The hope of America is not in applied Paganism, but in applied Christianity,” but he also affirmed that “we should freely and lovingly welcome to membership any Jew, Hindoo, or other religious socialist who is broad enough to work with us under the name of Jesus.”40 Apparently no Hindus took him up on this, but several Jews did, along with New Thought lecturers and a disproportionate share of ministers from denominations excluded from the Federal Council’s definition of “Christian.”

Orestes Brownson, 1803-1876. Courtesy Andover-Harvard Theological Library

The fellowship’s Christian Socialist newspaper featured careful exegetical arguments that “the Socialists can well claim that were Jesus here today he would be one of us”41 alongside declarations that “SOCIALISM IS RELIGION: not a religion, just religion. There is only one religion, and that is man’s expression of his humanity.”42 Some of the party’s leading spokespeople situated themselves right in the middle of the dialogue between these seemingly divergent theologies. In a widely reprinted article, Berkeley mayor Stitt Wilson affirmed, on the one hand, that “what America needs is a revival of genuine godliness and of primitive Christianity,” and, on the other, cited New Thought prophet Ralph Waldo Trine to the effect that “All men must be brought into ‘tune with the Infinite’ and all institutions of men must mirror the harmony and Freedom of the Good and the Free.”43 Charles Vail took time out from writing manuals of scientific socialism to publish The World’s Saviors, a comparative study of Krishna, Buddha, Jesus, and a dozen others. Vail concluded (in line with Theosophical teaching) that “all religions have their source in the Divine Wisdom of the Brotherhood of Perfect Men,” and that therefore “every religion is at its best as it comes from its Founder.”44

The CSF also sustained a more combative dialogue with those Marxists who wanted the Party to declare itself unequivocally for a philosophy of “scientific” materialism. That dialogue was contentious not only because the Christians’ status as “good socialists” was at stake, but also because so many of the debaters on the other side had defected from Christian socialism. In both Chicago and New York, the fellowship established local worshiping congregations only to see the leaders start declaring that “While it may not seem so at first sight, the scientific method is best, and it will win out in the end.”45 Such were the risks of dialogue in the socialist milieu: the religious loyalties of the participants were constantly changing.

A similar spirit of dialogue continued in the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR), which after World War I supplanted the Christian Socialist Fellowship as the most important network of left-wing social gospelers.46 Unlike the CSF, the FOR’s defining identity was pacifist rather than socialist, but most of its active members voted for the Socialist Party, at least after FOR member Norman Thomas had ascended to the top ranks of the party and made it explicitly open to non-Marxist varieties of socialism. Like many in the CSF, Thomas was a convert from a biblicist Christianity to a radical humanism. At the beginning of his editorial stint, he could declare that “for the ills that beset our race the spirit of Christ is the one sole medicament”47; by the end, he was committed to what he called the “implicit religion of radicalism”—a “religion of the future” that would build on the radical labor movement’s faith in the human capacity to build a better society.48 As Thomas shifted his energies to politics, the two sides of his internal dialogue were carried forward by editorial successors Kirby Page (whose Jesus or Christianity defended the “simple faith” of Jesus against the “alien and hostile elements” found in the church)49 and Devere Allen, whose Quakerism vested no special authority in Jesus.

Page and Allen aptly illustrate the common ground that kept the socialist dialogue (mostly) friendly for more than a hundred years. Page the Christian despised the church’s Constantinian compromises with power every bit as much as post-Christian Allen, while Allen admired the human Jesus enough to describe him as “the light of the world, throbbing with reality, incomparable” in a series on the theme “Would Jesus Be a Christian Today?”50 The glue that held their socialist dialogue together was the original Protestant critique of medieval Catholicism as an abandonment of the primitive faith of the apostles—a critique that was itself a distorted echo of the Hebrew prophets’ critique of priestly religion. Christian and post-Christian socialists found common ground because they shared both the culture and the ethos of Protestantism, and as a result their experience offered only a shaky precedent for the more inclusive dialogues of the late twentieth century. It could readily make room for the most radical of Reform Jews, but not so easily for Catholics or others who saw ritual, asceticism, or historical continuity as essential to faith.51

Still, the Fellowship of Reconciliation did much to inaugurate the contemporary era of dialogue. Beginning with John Haynes Holmes’s sermon that Gandhi was “The Greatest Man in the World,” and culminating with the publication of popular manuals of Gandhian technique, the FOR played the central role in introducing Americans to the nonviolent Hinduism of Mahatma Gandhi. Members of the FOR staff introduced Gandhian techniques to the bus boycotters, student sit-in leaders, and Freedom Riders of the civil rights movement. Yet, enthusiasm for Gandhi hardly involved an open dialogue with Hinduism. Gandhi was comprehensible to American socialists in part because he had learned the language of both liberal Protestantism and Theosophy during his studies in England; like his American admirers, he was fond of pitting Jesus against Christianity. Many of those admirers, in turn, shook their heads in bemusement “that a man of Gandhi’s ability could take seriously the heredity of professions, celibacy, and cow protection.”52 One historian has cited this passage as evidence that the FOR was deeply shaped by the Orientalism of Christian missionaries.53 The fact that the author, Curtis Reese, was not a Christian at all, but a major leader in the humanist movement, only underscores the point. He was no Christian, but he was still a Protestant, and that gave him a place at the table of socialist dialogue.

The Gandhian activism promoted by the FOR would eventually create a context for dialogue that was intercultural as well as interreligious, especially after the Vietnam War brought many American radicals into conversation with Vietnamese Buddhists. By the 1970s the FOR was in fact organized on a dialogical basis, with affiliated Catholic, Jewish, Buddhist, and Protestant denominational Peace Fellowships. But this turn, and the broader rise of dialogue in U.S. culture, occurred after organized socialist movements had ceased to be viable players in the American political scene. The Socialist Party in the 1940s and 1950s was little more than a vehicle for Norman Thomas’s “educational” presidential campaigns, while the Communist Party, after a period of vigorous “Popular Front” organizing in the 1930s, virtually collapsed as a result of revelations about Stalinist tyranny and red-baiting backlash. Many people continued to regard themselves as socialists, and in some ways they were more religiously diverse than ever. The anarchist Catholic Worker movement, the loosening of strictures against socialist affiliation during Vatican II, and the rise of liberation theology in Latin America all made it much easier for Roman Catholics to identify as “socialist” in the second half of the twentieth century.54 But when these folks came together in conversation with Protestants, Jews, and post-Christians, it was more likely in the context of civil rights or anti-war activism than under the rubric of socialism.

What, then, does the socialist experience of dialogue have to teach those of us who are committed to dialogues that move beyond the logic of Protestantism? A first lesson is that no single taxonomy of religious groups can apply in all contexts. We ordinarily think that “Christianity” is an inclusive category and “Protestantism” a subset thereof, and that is certainly true in many respects. But the Protestant influence on American culture reaches far beyond the boundaries of formal Christianity. It is possible, in some settings, for a dialogue that ostensibly brings together a “Christian,” a “Buddhist,” and a “Jew” to include only people whose way of thinking about religion is culturally Protestant. Certainly, that was the case for the dialogues staged at Brook Farm! Such dialogues may well have great value, but only if the Protestant presuppositions are acknowledged and worked through by all involved.

A broader implication of this point is that any dialogue involves some common presuppositions, values, and even prejudices, as well as the differences that are usually the focus of conversation. These commonalities, I suspect, are helpful only to the extent that they are acknowledged. Socialist dialoguers were brought together not only by their unacknowledged commitment to Protestantism, but also by their acknowledged commitment to socialism itself. And that was a great boon. A common vision of a better world made it possible for socialists to listen attentively to religious ideas that others might have dismissed as blasphemous or preposterous. Without such a vision, Cornelius Blatchly might never have given a hearing to Robert Owen, or Adin Ballou to Andrew Jackson Davis.

This vision of a better world may also help to explain the penchant of socialists to change their religious loyalties in the middle of the dialogue. Everyone discussed in this essay would fit in Orestes Brownson’s “movement party” of people who “desire something better.” As such, none of them were fully satisfied with the politics or the religion they had inherited. The practice of interfaith dialogue, like the practice of socialism, has an inherent appeal to such people, for it promises to introduce new ideas that might be better than the old. Yet, many dialogues are structured with the expectation that participants will speak out of the (more or less “stationary”) traditions they represent, rather than out of their personal questions and questings. Such structures may be a valuable corrective, making dialogue a bit more friendly to persons of more “stationary” disposition who would otherwise be underrepresented in dialogue. But the legacy of socialist dialogue reminds us that, ultimately, the table of dialogue must be set for progressive seekers and stationary traditionalists alike.[55]

Notes:

- Overviews of the Owenite movement include J. F. C. Harrison, Robert Owen and the Owenites in Britain and America: The Quest for the New Moral World (Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1969); Arthur Bestor, Jr., Backwoods Utopias: The Sectarian Origins and the Owenite Phase of Communitarian Socialism in America, 1663–1829 (University of Pennsylvania Press, 1950); and Donald E. Pitzer, “The New Moral World of Robert Owen and New Harmony,” in America’s Communal Utopias, ed. Donald E. Pitzer (University of North Carolina Press, 1997), 88–134. On the broader context of “workingmen’s” activism in the antebellum United States, see Sean Wilentz, Chants Democratic: New York City and the Rise of the American Working Class, 1788–1850 (Oxford University Press, 1984), and Jama Lazerow, Religion and the Working Class in Antebellum America (Smithsonian Institution Press, 1995).

- The history of the “Stilwellite” movement within Methodism is traced in William R. Sutton, Journeymen for Jesus: Evangelical Artisans Confront Capitalism in Jacksonian Baltimore (Pennsylvania State University Press), 91–95; and Kyle T. Bulthuis, “Preacher Politics and People Power: Congregational Conflicts in New York City, 1810–1830,” Church History 78, no. 2 (June 2009): 270–281.

- An Essay on Commonwealths (New York Society for Promoting Communities, 1822), 3–4, 27.

- Ibid., 46, 50.

- Many of these traditions are featured in Leigh Eric Schmidt, Restless Souls: The Making of American Spirituality (HarperSanFrancisco, 2005).

- On the gradual emergence of religious pluralism in the United States, see William R. Hutchison, Religious Pluralism in America: The Contentious History of a Founding Ideal (Yale University Press, 2003); on the current context for dialogue in the United States, see Diana L. Eck, A New Religious America: How a ‘Christian Country’ Has Now Become the World’s Most Religiously Diverse Nation (HarperSanFrancisco, 2001).

- President Barack Obama’s inaugural description of the United States as “a nation of Christians and Muslims, Jews and Hindus and nonbelievers” has been widely cited as evidence of this new understanding of dialogue.

- Robert Owen, The Book of the New Moral World, part 4, Explanatory of the Rational Religion (James Watson, 1852); and Harrison, Robert Owen and the Owenites, 92–139.

- “Sunday Lectures at Lower Julien Hall,” Boston Investigator, April 23, 1831, 15.

- “Prospectus of The Free Enquirer,” The Free Enquirer, second series, 1 (October 29, 1828): 5.

- Henry Mayer, All On Fire: William Lloyd Garrison and the Abolition of Slavery (St. Martin’s Press, 1998), 102–103.

- “Imprisonment of Abner Kneeland” and “Petition for the Pardon of Abner Kneeland,” Liberator, July 6, 1838.

- Boston Investigator, April 17, 1835.

- The definitive study of the Fourierist movement in the United States is Carl Guarneri, The Utopian Alternative: Fourierism in Nineteenth-Century America (Cornell University Press, 1991). On Fourier himself, see Jonathan Beecher, Charles Fourier: The Visionary and His World (University of California Press, 1986).

- The most recent of many studies of Brook Farm is Sterling F. Delano, Brook Farm: The Dark Side of Utopia (Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2004).

- John Greig, cited in John Humphrey Noyes, History of American Socialisms (J. B. Lippincott, 1870), 280.

- B. J. Thomas to “My Dear Friend,” 9 June 1845, in John Thomas Codman, Brook Farm: Historic and Personal Memoirs (Arena Publishing Company, 1894), 270.

- Georgiana Bruce Kirby, “My First Visit to Brook Farm,” Overland Monthly 5 (July 1870): 9–19, in The Brook Farm Book: A Collection of First-Hand Accounts of the Community, ed. Joel Myerson (Garland, 1987), 107.

- B. J. Thomas to “My Dear Friend.”

- “Mr. Brownson’s Notice of Fourier’s Doctrine,” Phalanx 1, no. 14 (July 13, 1844): 197–198.

- Octavius Brooks Frothingham, Memoir of William Henry Channing (Houghton Mifflin, 1886), 225; and Sterling F. Delano, “A Calendar of Meetings of the ‘Boston Religious Union of Associationists,’ 1847–1850,” Studies in the American Renaissance (1985), 187–267.

- Notable among recent studies of spiritualism are Ann Braude, Radical Spirits: Spiritualism and Women’s Rights in Nineteenth-Century America (Beacon Press, 1989); Bret E. Carroll, Spiritualism in Antebellum America (Indiana University Press, 1997); Robert S. Cox, Body and Soul: A Sympathetic History of American Spiritualism (University of Virginia Press, 2003); and John B. Buescher, The Other Side of Salvation: Spiritualism and the Nineteenth-Century Religious Experience (Skinner House, 2004).

- Catherine Albanese, A Republic of Mind and Spirit: A Cultural History of American Metaphysical Religion (Yale University Press, 2007), 206–220.

- Andrew Jackson Davis, The Great Harmonia, 8th ed., 5 vols. (Colby & Rich, 1884), 4, 10; and Davis, The Penetralia, Being Harmonial Answers to Important Questions (Bela Marsh, 1856), 26.

- Adin Ballou, Practical Christian Socialism: A Conversational Exposition of the True System of Human Society (Fowler and Wells, 1854); and Edward K. Spann, Hopedale: From Commune to Company Town, 1840–1920 (Ohio State University Press, 1992).

- Adin Ballou, “Spirit Manifestations—No. 1,” Practical Christian 12, no. 11 (September 27, 1851): 42. Ballou elaborated his views in An Exposition of Views Respecting the Principal Facts, Causes, and Peculiarities involved in Spirit Manifestations (Bela Marsh, 1853).

- Braude, Radical Spirits, 170–173.

- Mari Jo Buhle, Women and American Socialism, 1870–1920 (University of Illinois Press, 1981); see also Paul Buhle, Marxism in the United States: Remapping the History of the American Left, rev. ed. (Verso, 1991), 67–70.

- Henry George, Progress and Poverty (W. M. Hinton, 1879); Laurence Gronlund, The Cooperative Commonwealth in Its Outlines: An Outline of Modern Socialism (Lee and Shepard, 1884); and Edward Bellamy, Looking Backward, 2000–1887 (Ticknor and Company, 1888).

- J. Gordon Melton, “The Theosophical Communities and Their Ideal of Universal Brotherhood,” in America’s Communal Utopias, ed. Donald E. Pitzer (University of North Carolina Press, 1997), 396–418.

- The vision of this Fellowship is amply represented in Socialist Spirit, published 1901 and 1903.

- W. J. Ghent, “The Collectivist Society,” The Commons 9, no. 2 (March 1904): 89–90; E. E. Carr, “The Christian Socialist Fellowship: A Brief Account of its Origins and Progress,” Christian Socialist 4, no. 16 (August 15, 1907): 5; and Charlotte Perkins Gilman, His Religion and Hers: A Study of the Faith of Our Fathers and the Work of Our Mothers (Century, 1923).

- “The Christian Socialist Fellowship,” Christian Socialist 2, no. 20 (October 15, 1905): 7. The quote is from a letter by Robert W. Irwin.

- Thomas Wakefield Goodspeed, University of Chicago Biographical Sketches (University of Chicago Press, 1922), 351–352.

- Zane L. Miller, Boss Cox’s Cincinnati: Urban Politics in the Progressive Era (Oxford University Press, 1968), 143–145; “Pacifist Whipped in Kuklux Style,” The New York Times, October 30, 1917, 3; “Ohio: Two & None,” Time, January 13, 1936. Also see Daniel R. Beaver, A Buckeye Crusader: A Sketch of the Political Career of Herbert Seely Bigelow (1957).

- Fred W. Shorter, “An Experiment in Radical Religion,” Radical Religion 1, no. 4 (Autumn 1936): 19–22.

- W. A. Corey, “The Benjamin Fay Mills Movement in Los Angeles,” Arena 33, no. 187 (June 1905): 593–595; “Rev. Benj. Fay Mills Dead,” The New York Times, May 2, 1916, 13; Carey McWilliams, Southern California: An Island on the Land (Peregrine Smith, 1973), 257; and Beryl Satter, Each Mind a Kingdom: American Women, Sexual Purity, and the New Thought Movement (University of California Press, 1999), 205.

- Shorter, “An Experiment in Radical Religion.”

- The best introduction to the role of religion in the first two decades of Socialist Party history is Socialism and Christianity in Early 20th Century America, ed. Jacob H. Dorn (Greenwood Press, 1998). For general histories of the party, see David A. Shannon, The Socialist Party of America (Macmillan, 1955); Howard Quint, The Forging of American Socialism: Origins of the Modern Movement (University of South Carolina Press, 1953); Ira Kipnis, The American Socialist Movement, 1897–1912 (Monthly Review Press, 1952); Frank A. Warren, An Alternative Vision: The Socialist Party in the 1930s (Indiana University Press, 1974); Buhle, Marxism in the United States; Anthony V. Esposito, The Ideology of the Socialist Party of America, 1901–1917 (Garland, 1997); and Seymour Martin Lipset, It Didn’t Happen Here: Why Socialism Failed in the United States (Norton, 2000).

- E. E. Carr, “The Christian Socialist Fellowship,” Christian Socialist 2, no. 20 (October 15, 1905): 4.

- Ibid., 10–13.

- Everett Dean Martin, “Why I Am a Socialist,” Christian Socialist 6, no. 3 (February 1, 1909): 2.

- J. Stitt Wilson, “Individual and Social Salvation,” Christian Socialist 4, no. 11 (1907): 1–3.

- Charles Vail, The World’s Saviors (Macoy Publishing and Masonic Supply Company, 1914), 194.

- “What Bentall Thinks,” Christian Socialist 5, no. 24 (December 15, 1908): 5.

- The Fellowship of Reconciliation is the subject of two outstanding recent histories: Patricia Appelbaum, Kingdom to Commune: Protestant Pacifist Culture Between World War I and the Vietnam Era (University of North Carolina Press, 2009); and Joseph Kip Kosek, Acts of Conscience: Christian Nonviolence and Modern American Democracy (Columbia University Press, 2009).

- “An Interpretation and Forecast,” The New World 1, no. 1 (January 1918): 4–5.

- Norman Thomas, “The Implicit Religion of Radicalism,” World Tomorrow 3, no. 8 (August 1920): 231–233.

- Kirby Page, Jesus or Christianity (Doubleday, 1929), 1.

- Devere Allen, “Would Jesus Be a Sectarian Today?” World Tomorrow 11, no. 11 (November 1928): 458–461.

- The one important exception to the anti-ritualism of the socialist dialogue was the involvement of radical Anglo-Catholics, many of whom were also formative leaders in the New Thought movement. For a representative example of this strand of socialist thought, see Jacob H. Dorn, “ ’Not a Substitute for Religion, but a Means of Fulfilling It’: The Sacramental Socialism of Irwin St. John Tucker,” in Socialism and Christianity, ed. Dorn, 137–164.

- Curtis Reese, “Mahatma Gandhi’s Ideas,” The World Tomorrow 8, no. 5 (May 1930): 229.

- Leilah C. Danielson, “ ’In My Extremity I Turned to Gandhi’: American Pacifists, Christianity, and Gandhian Nonviolence, 1915–1941,” Church History 72, no. 2 (June 2003): 361–388.

- Early in the twentieth century, the Catholic hierarchy was unrelentingly hostile to socialism, even though, beginning with Rerum Novarum in the 1890s, popes and bishops promoted a middle path between capitalism and socialism that was well to the left of mainstream Protestant thinking on the economy. The rigidity of church authority made active involvement in socialist movements virtually unthinkable for most observant Catholics. This began to change in the 1930s, when the Catholic Worker in the United States and Esprit in France began promoting more radical interpretations of Catholic social teaching. Though the Catholic Worker movement’s vision was more anarchist than socialist, it broke the taboo on Catholic affiliation with all stripes of economic radicalism. See John C. Cort, Christian Socialism: An Informal History (Orbis Books, 1988), for an evocative account of religious socialism from the perspective of one Catholic who came to socialism via the Catholic Worker movement.

- I am most grateful to Kip Richardson for his assistance in researching this article.

Dan McKanan is Ralph Waldo Emerson Unitarian Universalist Association Senior Lecturer in Divinity at Harvard Divinity School. His most recent book is The Catholic Worker After Dorothy: Practicing the Works of Mercy in a New Generation (2008), and he is working on a general history of the religious left in the United States.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.