Dialogue

Signs from Field, Forest, and Stream

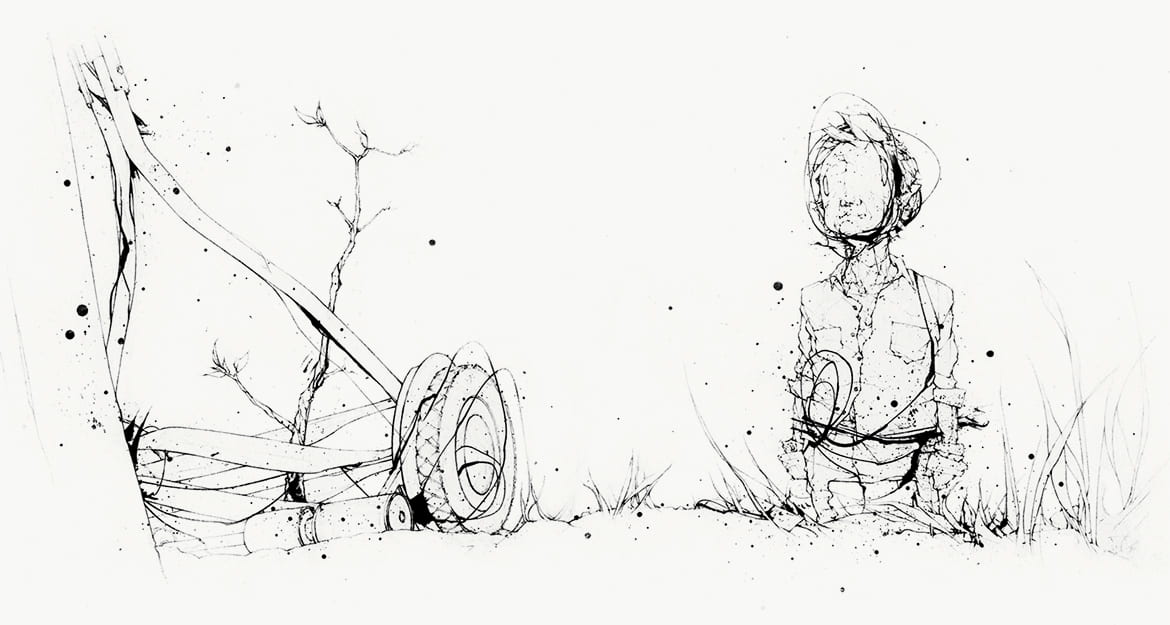

Illustration by Andrew Zbihlyj

By Brett Grainger

As he approached the end—not the very end, when sound stumbled in the dark socket of his mouth and only the eyes spoke, but in the last days—my grandfather and I sat outside the hospital and talked about trees. The wind and sun played on the leaves of a nearby poplar, its thousand tiny hands shaking in silvery applause. Pointing his own shaking hand, my grandfather mused on the tree’s secret life, the hidden forces that pulled energy down from the sky and up from the firmament to fire fresh shoots several stories above our heads. He’d often hymned the beauty and order of nature’s architecture—the intricate shutter of the iris, the delicate hinge of a sparrow’s wing—how it intimated a divine architect. But this wasn’t argument or evidence. It was a kind of presence.

As Christians have for millennia, my grandfather read the natural world as a third testament, an endless sermon on the truth, beauty, and justice of God. The key lay in learning to read the book of nature together with the books of scripture. On my visits to the family farm, he would rise from the couch and lead me on a walk around the property, reciting the moral and spiritual lessons he’d gleaned from the irregular fold of a hill, the zigzag bend of a creek, the webbed sprawl of a rhubarb leaf. A lifelong evangelical, my grandfather scanned the natural world for hidden codes with the same reverent intensity he thumbed his dog-eared King James Bible.

One day, we walked round the back of the garage where an old hand-drawn lawn roller leaned up against the wall. Inside its U-shaped aluminum arms, the trunk of a poplar had been whittled to a pencil point. Some years back, he’d come to retrieve the roller, only to find that a tree had sprouted up inside the handle. Rather than break the sapling, he left the tool where it lay and pondered what providence might be trying to tell him. “Then,” he said, fixing me with his grey eyes, “God sent the beaver.” One day, to his surprise, he found the tree timbered and the lawn roller freed up for use again.

In such minor episodes, my grandfather read maxims of the spiritual life. “Sometimes,” he said, “the Lord puts an obstacle in our way that makes us useless. We’re stuck like that lawn roller. But, in his good time, the Lord sends a messenger to remove the obstacle and put us back to use again.” His job, he reckoned, was to figure out what he’d been freed up to do, like he had in the late 1960s, when an ornery Holstein had let loose and kicked him in the leg, shattering his femur. When the cast came off three months later, he sold the whole dairy herd and took up carpentry, a career more suited to his temperament. Message received.

It’s been a while since I began to sense a contradiction between what evangelicals say in public about nature and the private disciplines and practices that sustain their day-to-day spiritual lives. Political leaders like Michelle Bachman parade their suspicion of global warming and rail against the “nature worship” of “pagan” environmentalists. Creation, they bellow, was born a beast of burden. “Fill the earth and subdue it,” in the words of Genesis. In popular imagination, the evangelical relationship to nature is summed up in the image of Sarah Palin perched in a helicopter, picking off wolves with a high-powered rifle.

In some ways, Palin and my grandfather weren’t so far apart. God may have sent the beaver to teach him a lesson, but my grandfather had his own lessons to teach the beavers, especially when they acted as benighted pests that dammed the creek in the spring, flooding out the road to the farm. Every year, he managed to kill a few with traps. He climbed down in the cold water and ripped apart the intricate barricade, branch by branch. In a few weeks, however, the holes would be patched and the road back under water. The stalemate continued for years. Then the human escalated the conflict. He packed the dam with three sticks of dynamite and blew the whole thing to kindling, along with half the driveway. For a spell, nature knew its place.

Historians and theologians have long debated whether to view Christianity’s relationship to nature as one of reverence or mastery. I don’t much see a point in choosing. Life is rarely so tidy, or so uninteresting. Rather than approach sacramental and instrumental approaches to nature as mutually exclusive, we do better to think of an accommodation. All too often, categories such as enchantment and disenchantment, sacred and secular, reverence and subjugation, turn out to be two sides of the same leaf. This isn’t a uniquely modern story. In Landscape and Memory, Simon Schama argues, “against the grain of much environmental writing,” that Western culture has worshiped and mythologized nature, “even while it has been busy destroying forests” and draining fens (213). Nor is it a uniquely Christian story. Today, Latter-day Saints go on pilgrimages to the “sacred grove” outside Palmyra, New York, where Joseph Smith, Jr., the prophet of Mormonism, received his first divine visitation from two white-robed men, God the Father and Jesus Christ. What Mormons don’t tell you is that Smith and his family likely cut down most of the grove in the years after the revelation.

In other words, it’s not always true that if you scratch religious experience, you’ll find romanticism underneath. As the historian of American religion Perry Miller sniffed, one shouldn’t expect “the yelping and jerking converts” at Cane Ridge—the landmark Kentucky revival of 1801 that helped kick off the Second Great Awakening—to show much appreciation for a beautiful sunset. “Anyone who knows the New England peasantry,” he continued, “knows that you can never get an authentic Vermont farmer to admire the view.” In one sense, Miller was right. The best romantics were urban, cultivated, and independently wealthy. Most of the great English landscape painters could praise the edenic pleasures of agriculture and animal husbandry because they didn’t know the first thing about it. Growing up on a dairy farm surely inoculated my grandfather against the beautiful lies of John Constable, who never milked a cow in his life.

And yet, the great evangelical revivals were born in field, forest, and stream. From the woodland meetings that broke out in 1730 among persecuted Protestants in Salzburg to the mammoth camp meetings of antebellum Kentucky, evangelical belief and practice were forged in close connection with the world of nature. Early itinerants and circuit riders practiced a piety close to the rhythms of nature: they sang hymns, worked out sermons, and prayed and meditated on God’s two books, nature and scripture, while pressing their exhausted mounts from settlement to settlement. Thomas Coke, first Methodist bishop, confided in his journal his “most delicate entertainment” of “ingulphing” himself in the woods. “I seem then,” he wrote, “to be detached from every thing but the quiet vegetable creation, and my god.” Illustrating this experiential bond between heart religion and nature piety, he quoted a hymn by Isaac Watts:

I’ll carve thy passion on the bark:

And every wounded Tree

Shall drop, and bear some mystic mark

That Jesus died for me.The Swains shall wonder, when they read

Inscrib’d on all the Grove,

That Heaven itself came down and bled

To win a mortal’s Love.

The early literature of evangelical spirituality abounds with the contemplation and meditation of nature. In colonial America, the diary of David Brainerd, early missionary to Native Americans, set a distinctive pattern of conversion. “Unspeakable glory” appeared to Brainerd as he was walking in a “dark thick grove,” the hierophany offering glimpses of a “new world” around him. A century later, Charles Grandison Finney, a leader of the Second Great Awakening, secured his salvation in a similar way during a walk in the woods. Finney later described a debate with a young man flirting with Universalism; after the argument, Finney writes, the man “went into the woods” and “gave his heart to God.”

Perhaps we’ve paid too much attention to what evangelicals say in public about the evidentiary potential of “creation science” and “intelligent design,” and not enough to the disciplines and rituals of private piety. Design, after all, offers no answers to the really crucial evangelical questions, including the one that mattered most for my grandfather: namely, how to grab hold of the promise of life abundant through a personal relationship with Life itself. For him, the new birth was no spiritual metaphor. The “new man” was a pressing, felt reality, one inaugurated by a regeneration of the senses. As one hymn puts it:

Heav’n above is softer blue,

Earth around is sweeter green!

Something lives in ev’ry hue

Christless eyes have never seen.

In other words, what my grandfather and David Brainerd saw in nature could not be parsed through an elegant equation or pressed between slides and peered at through a microscope. For those with the ears to hear and the eyes to see, the rudest sapling shuddered in the image of the tree of life and the shallowest creek shadowed forth currents of spiritual refreshment.

Brett Grainger is a doctoral candidate in American religious history at Harvard University and the author of In the World but Not of It: One Family’s Militant Faith and the History of Fundamentalism in America (Walker and Company).

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.