In Review

Shylock Re-Shot

By Kevin Madigan

Pondering the restraining influence of the monotheistic traditions, the brilliant German poet Heinrich Heine (1797-1856) once imagined, in an uncharacteristically somber moment, what it would be like if the religions ever completely lost their powers of restraint: “If one day Satan or sinful pantheism should conquer, there will gather over the heads of the poor Jews a tempest of persecution that will far surpass all they have had to endure before.” A century later, the Prince of Darkness transgressed every imaginable geographical and moral border, and Heine’s prophecy broke in a storm of iniquity whose dimensions would have beggared even his broad imaginative powers. Heine’s own relationship with Judaism and Jews was famously ambivalent, and it is that divided relationship that allowed him to ponder the possibility of collective disaster with such curious distance and impassivity. (“What greater martyrdom awaits them in the future!” he once observed, less in sympathy than in amazed frustration.) That he was able to imagine such a cataclysm at all is owing to a number of factors. Not the least of these were his lifelong reflections, sometimes obsessive, on Shylock and on Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice, which he placed among the tragedies.

Long before the Nazi storm had broken, anti-Semites in America and Europe had made frequent use of Shylock. One Australian Labor M.P. revealed, in a pamphlet entitled The Kingdom of Shylock, that the Great War had been planned and financed by Jewish imperialists in England. The otherwise anonymous E. S. Spencer could publish a book entitled Democracy or Shylocracy? (1920), fruitlessly hoping to achieve fame by warning the world against the Jewish corruption of finance, politics, and society. Closer to home, Shylock entered the rants and screeds of Ezra Pound, Father Coughlin, and similar crackpots, who saw in him an archetype of “Jewish” vengeance, greed, and legalism, not to mention fondness for international conspiracy. The most prolific German anti-Semite of the interwar era, Theodore Fritsch (author of the often reprinted Handbuch der Judenfrage (Handbook of the Jewish Question), once observed, in a volume preposterously entitled The Origins and Nature of Jewry, that readers in search of the true Jewish character should ignore Gotthold Lessing’s Nathan the Wise and focus on Shakespeare’s Shylock. Fritsch died in 1933, just in time to see the accession to power of a regime that would translate all his anti-Semitic fantasies into horrible reality.1

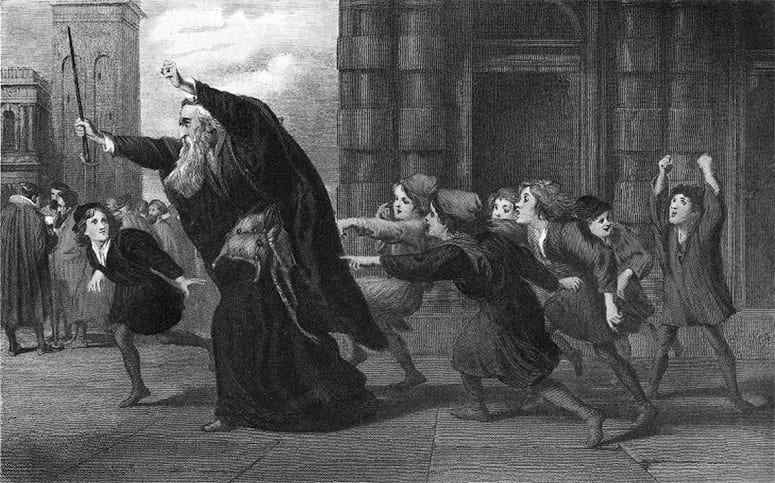

An illustration entitled “Shylock, After the Trial,” by Sir John Gilbert, from a nineteenth-century edition of Shakespeare’s works.

At a time when all drama from the Allied nations, and much “degenerate” drama from home, was banned in the Reich, the Nazis put on countless productions of Shakespeare and subsidized tickets and organized excursions to his plays. He was, every party loyalist knew, essentially Germanic in spirit: Hadn’t Hamlet, the Nordic Dane, attended the University of Wittenberg? Shakespeare was, moreover, patriotic, admitted the need for strong political leaders, and acknowledged the supremacy of the State. Just the playwright for the Führer and his Thousand Year Reich. The Führer’s Education Department issued a pamphlet called Shakespeare: A Germanic Writer. Literary critics chimed in with “Nordic interpretations” of the plays. Hamlet himself was made to stand in for Germany. The way in which he lost his inheritance allegorically prefigured the outrages of Versailles. Eugenicists discovered to their delight that Shakespeare was himself an enthusiast for racial cleansing—one of the earliest. And the Bard’s portrait proved that he, too, was Nordic—thank God!—in racial character. True, Othello could not be shown—too much racial “mixing.” Nor could Antony and Cleopatra, which was perverse, as well as effeminate. But almost all of his other plays were put on, some many times. Even as the Luftwaffe was blitzing London and leveling Coventry, the Germans never lost their affection for “our Shakespeare” (unser Shakespeare), nor ceased to put his plays into production.2

Again and again. In 1933, The Merchant of Venice was staged no fewer than 20 times. In the next five years, it would be put on more than 30 times. Though they had to deal with the difficulties of Jessica’s “interracial” marriage with Lorenzo (by, for example, making Jessica an Aryan child adopted by Shylock), Hitler’s willing directors rarely failed to exploit the anti-Semitic possibilities of the play. In case the audience failed to apprehend these, the Nazis helpfully installed commentators to underline them. In a 1942 production in Berlin, the director planted extras in the audiences to shout and whistle when Shylock appeared, thus cuing the audience to do the same.

Baldur von Schirach, the Gauleiter of Vienna (and sometime head of the Hitler Jugend), deported, by his own proud admission, “tens of thousands of Jews from this city.” Many perished as a consequence. (Schirach was eventually convicted of crimes against humanity at Nuremberg.) By the time Vienna’s Jews were mostly deported, Schirach, the son of a theater director, ordered the production of The Merchant of Venice (May 1943). Shylock was played by Werner Krauss, best known for having taken on the leading role (many roles, actually) in The Jew Suess. This was a Nazi propaganda film made under the charge of none other than Josef Goebbels. Screened in parts of Nazi-occupied Europe on the eve of SS “actions,” it was intended to justify cruelties to come and to remove sympathy for victims. One critic, in an article entitled “Shylock der Ostjude” (“Shylock the Eastern European Jew”), hailed Krauss for having achieved so convincing a simulacrum of the pathological “East European Jewish type.” Here, Nazi genocidal aims and achievements were explicitly tied to the didactic staging of Merchant. After viewing the play, the audience was to understand the necessity of Schirach’s rigorous actions and presumed to agree with his own self-assessment: that in sending tens of thousands of Viennese Jews to their deaths, he had made “a positive contribution to European culture.”

The Nazi affection for Merchant stands in stark contrast to Hollywood’s long pretense, increasingly understandable over the course of the twentieth century, that the play did not exist. Although about 10 made-for-television versions have been produced, Hollywood hadn’t taken on the project at all since the silent era. It’s not an easy project to take on. The anti-Semitic use of the play, and in particular the character of Shylock, must have discouraged many talented directors. Beyond that, Shakespeare’s texts (unlike the Gospels, for example) are not known to many American movie viewers, and few are going to be as interested in the depiction of the character of Shylock as the death of Jesus of Nazareth.

Al Pacino as Shylock in Michael Radford’s recent film The Merchant of Venice. Steve Braun/Sony Pictures Classics

That’s a shame, because Michael Radford’s Merchant of Venice (with Al Pacino’s bravura performance as Shylock) represents one of the best adaptations of an important Western cultural text to the silver screen ever made. While director-writer Radford (Il Postino) “picks and chooses,” his screenplay does not distort. He does not make things up or presume to improve upon Shakespeare’s script. The characters speak English, which Radford knows to be the lingua franca of Elizabethan England. There are no historical or textual howlers, nothing unintentionally funny. There are no cartoonish Jews. The blood is minimal (the spit, alas, is not). The relationship of Jewish father and daughter is extremely affecting, the portrayal of Jewish social life sympathetic and of Jewish religious life profoundly respectful. The Christians are not heroic. While not quite contemptible, they are not in the least admirable, either.

What really makes Radford’s film a triumph, though, is that he makes Shylock sympathetic without making him either likeable or villainous. Even though Radford expunged from the text some of the lines in which he seems most vile, Shylock still comes off badly. Radford never tries to make us like him. However, he does make us understand the conditions that help to explain him. A prologue (probably necessarily) reminds the viewer that Jews in sixteenth-century Venice were ghettoized, pressed into the unpopular role of moneylenders, and stigmatized visually by red hats, making them more readily vulnerable to abuse. The first time we see Shylock, socializing on the Rialto, Antonio spits on him as a usurer. Meanwhile, the other Christians are—besides spitting—drinking, gambling, and whoring, their essential paganism underscored by the lavish background of Venice, whose gorgeousness Radford uses to great effect.

Radford also never lets us forget the things that Shakespeare wanted us to remember. That Shylock is in danger of losing a great deal of money. That he loses his beloved daughter (who also steals from him). That Antonio is allowed to get away, in court and by Christian magistrates, without paying his debt. That Shylock rightly calls for “justice” to be done. That he must convert and is banned from the synagogue. That he is, in the end, brought low by Christians. All of this is expressed beautifully by Pacino and by Zuleikha Robinson, who plays Jessica. Radford makes it clear that far, far more dear to him than the loss of his bond is the loss and betrayal of his daughter and his ancestral faith. When Shylock learns he is to be converted, Pacino majestically buries his face in his hands, ruthlessly cut off from the rich religious tradition and the Venetian community in which he had been cradled and nourished. It’s one of the most affecting scenes in the movie, second in dramatic power perhaps only to the final scene, in which Radford brilliantly focuses on Jessica, who ponders with deep ambivalence all she has given up by marrying a Christian and leaving her father.

By the close of the film, we can only agree with Shylock that he has been “more sinned against/Than sinning.” Seeing the play with the knowledge of its exploitation by Hitler, and in the aftermath of the Holocaust, one is almost tempted to say of what happens to Shylock what Samuel Johnson said of the fate of Desdemona: “it is not to be borne.”

Kevin Madigan is Associate Professor of the History of Christianity at Harvard Divinity School. His book Ordained Women in the Early Church will be published by Johns Hopkins this spring.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.

Um…you might want to take out your “ more sinned against/Than sinning” point—that’s Lear, not Shylock. As we actual Jews say: Oy vey.

(I apologize if that comment sounded snotty—it was meant to be funny. Bit of a tone fail, I’m afraid.)