Featured

Rethinking the Study of African Indigenous Religions

Indigenous traditions continue to define the African personality.

By Jacob K. Olupona

It is a well-known fact that religion continues to play a central and vital role in the lives of African people. The much-cited dictum by the doyen of African religious studies, the recently deceased John Mbiti, that “Africans are notoriously religious” still holds true (though I prefer to use the word “deeply”).1 While, officially, statistics suggest that African Christians and Muslims constitute about 80 percent of the total population, and African indigenous religion constitutes about 20 percent, these statistics do not reflect the truth of the African situation. The African religious worldview is primarily indigenous, although Islam and Christianity continuously respond to its viability and strength through their transitive approaches, their theologies, and their knowledge systems. Similarly, indigenous religion, worldviews, and rituals such as rites of passage and other religious performances are permeated by other religions, culture, and society in general. Initially, Christian missionaries and propagators of Islam assumed that indigenous religion would eventually fizzle out, while Islam and Christianity would dominate the African religious scene. Scholarship has since proved, however, that the tenacity of indigenous religion is evident in all spheres of African life.

Jacob K. Olupona. HDS Photograph

As scholars of the comparative study of religions in Africa, we must begin to rethink the study of African religion in the twenty-first century in order to avoid the continuous mis-assessment of the resilience of indigenous traditions. Indigenous religions are definitive of the African identity, as African religion and cultures provide the language, the ethos, the knowledge, and the ontology that enable the proper formation of African personhood, communal identity, and values that constitute kernels of African ethnic assemblages. Consequently, despite all of Christianity and Islam’s claims to dominance and their propagandist machinery in demonizing indigenous religion, African religion still provides significant meaning to African existence in many ways. In this essay, I attempt to refocus the centrality of indigenous religion, not only in defining African cosmology and an African worldview, but also in defining the African personality in the twenty-first century.

What Is African Religion? The Big Question

The range of African indigenous beliefs and practices has been referred to as African traditional religions in an effort to encompass the breadth and depth of the religious traditions on the continent.2 The diversity of the traditions themselves is tremendous, making it next to impossible for all of them to be captured in a single presentation. Even the word “religion,” used in reference to these traditions, is in itself problematic for many Africans, because it suggests that religion is separate from other aspects of one’s culture, society, and environment. For many Africans, religion is a way of life that can never be separated from the public sphere, but instead informs everything in traditional African society, including politics, art, marriage, health, diet, dress, economics, and death.

Despite the plethora of denominations and sects, African religions continue to be viewed as single entities,3 and their (our) religions are perhaps the least understood facet of African life. Many foreigners who come to Africa become fascinated by ancestral spirits and spirits in general, as if the mystique of African religions is the only aspect of African spirituality that can hold scholarly interest.4 There are several common features of African indigenous religions that suggest similar origins and allow African religions to be treated as a single religious tradition, just as Christianity and Islam are.

First, there is a supreme being who created the universe and every living and nonliving thing to be found within the universe. Second, spirit beings occupy the next tier in the cosmology and constitute a pantheon of deities who often assist the supreme God in performing different functions. John Mbiti divides spirit beings into two types, nature spirits and human spirits. Each has a life force but no concrete physical form. Nature spirits are associated with objects seen in nature, such as mountains, the sun, or trees, or natural forces such as wind and rain. Human spirits represent people who have died, usually ancestors, in the recent or distant past.5 Third, the world of the ancestors occupies a large part of African cosmology. As spirits, the ancestors are more powerful than living humans, and they continue to play a role in community affairs after their deaths, acting as intermediaries between God and those still living.6 Finally, I would add that Africans live their faith rather than compartmentalize it into something to be practiced on certain days or in particular places. Catholic moral theologian Laurenti Magesa argues that, unlike clothes, which one can wear and take off, for Africans, religion is like skin that cannot be so easily abandoned.7 Mbiti also captures this unique aspect in the following passage:

Because traditional religions permeate all the departments of life, there is no formal distinction between the sacred and the secular, between the religious and non-religious, between the spiritual and the material areas of life. Wherever the African is, there is his religion: he carries it to the fields where he is sowing seeds or harvesting a new crop; he takes it with him to the beer party or to attend a funeral ceremony; . . . Although many African languages do not have a word for religion as such, it nevertheless accompanies the individual from long before his birth to long after his physical death. Through modern change these traditional religions cannot remain intact, but they are by no means extinct. In times of crisis they often come to the surface, or people revert to them in secret.8

The most difficult task I face in characterizing African indigenous spiritual traditions is accounting for their diversity and complexity. One approach is to outline, in a systematic way, the essential features of these traditions without paying much attention to whether or not the traditions fit into the pattern of religions already mapped out by Western theologians and historians, who use Western religious traditions as the standard by which to measure religions in other parts of the world. African religions should be studied on their own terms, examined through their own frames rather than set in a Judeo-Christian framework. Such an approach should endeavor to provide not only an awareness of sociocultural contexts but also to narrate the historical dimensions of these traditions.

Myths, Rituals, and Cosmologies

Narratives about the creation of the universe (cosmogony) and the nature and structure of the world (cosmology) provide a useful entry to understanding African religious life and worldviews. These narratives come to us in the form of “myths.” Unlike its popular usage, in scholarly language myths are sacred stories believed to be true by those who hold on to them. Myths reveal critical events and episodes—involving superhuman entities, gods, spirits, ancestors—that are of profound and transcendent significance to the African people who espouse them. As oral narratives, myths are passed from one generation to another and represented and reinterpreted by each generation, who then make the events revealed in the myths relevant and meaningful to their present situation.9

In spite of the heuristic value of V. Y. Mudimbe’s distinction between myth and history in Africa, and by extension the cohesion of oral and written narratives,10 the notion that myth is nonrational and unscientific while history is critical and rational is false. For one thing, a sizable number of African myths deal with events considered to have actually happened as narrated by the people themselves or as reformulated into symbolic expressions of historical events. Symbolic and mythic narratives may exist side by side with narratives of legends in history that bear similar characteristics with motifs and events of creation or coming to birth. On the other hand, we now know from research and archival sources that, by their very nature, sources and records of missionaries, colonial administrators, and indigenous elites, which were preserved by colonial administrations, were equally susceptible to distortion and perforation, having been written from the angle of an invented modernity that the colonizer considered superior to the worldviews of local peoples.

A sizable number of African myths deal with events considered to have actually happened as narrated by the people themselves or as reformulated into symbolic expressions of historical events.

As with myths the world over, African mythology includes multiple, often contradictory, versions of the same event. African cosmogonic narratives posit the creation of a universe and the birth of a people and their indigenous religions. These are also stories about how the world was put into place by a divine power, usually a supreme god, but in collaboration with other lesser supernatural beings or deities, who act on his behalf or aid in the creative process.11 The mechanisms and techniques of creation vary from story to story and from one tradition to another. While scholars have often argued that African indigenous accounts of creation were ex nihilo (created out of nothing), as the biblical account of creation is often portrayed,12 African cosmological narratives generally indicate that there is never one pattern governing how creation happens. All over the continent, cosmological myths describe a complicated process, whether the universe evolves from preexisting objects or from God’s mere thought or speech. In whatever way it happens, African cosmological narratives are similarly complex, unsystematized, and multivariate, and they are the bedrock for indigenous value systems. Even within a single ethnic group or clan, there are often highly contested and even opposing stories or viewpoints when it comes to creation accounts, thus allowing for flexibility and hermeneutic creativity. The absence of centralized and unified cosmologies indicates the multifaceted nature of African religious life and worldviews.

Although it is difficult to generalize about African traditional cosmology and worldviews, a common denominator among them is a three-tiered model in which the human world exists sandwiched between the sky and the earth (including the underworld)—a schema that is not unique to Africa but is found in many of the world’s religious systems as well. A porous border exists between the human realm and the sky, which belongs to the gods. Similarly, although ancestors dwell inside the earth, their activities also interject into human life, which is why they are referred to as the living dead.13 African cosmologies, therefore, portray the universe as a fluid, active, and impressionable space, with agents from each realm bearing the capabilities of traveling from one realm to another at will. In this way, the visible and invisible are in tandem, leading practitioners to speak about all objects, whether animate or inanimate, as potentially sacred on some level.

Ritual practices are central to the performance of African religion. Ceremonies of naming, rites of passage, death, and other calendrical rites embody, enact, and reinforce the sacred values communicated in myths. They often dictate when the community honors a particular divinity or observes particular taboos. Divinities and ancestors have personalized annual festivals during which devotees and adepts offer sacrificial animals, libations, and favored foods to propitiate them. Ritual enables supernatural beings to bless individuals and the community with sustenance, prosperity, and fecundity.14 Rites of passage, such as initiation ceremonies, are rituals marking personal transitions recognized and celebrated by the community. Each ceremony denotes passage from one social status to another and is an opportunity to celebrate the initiates on their journey.

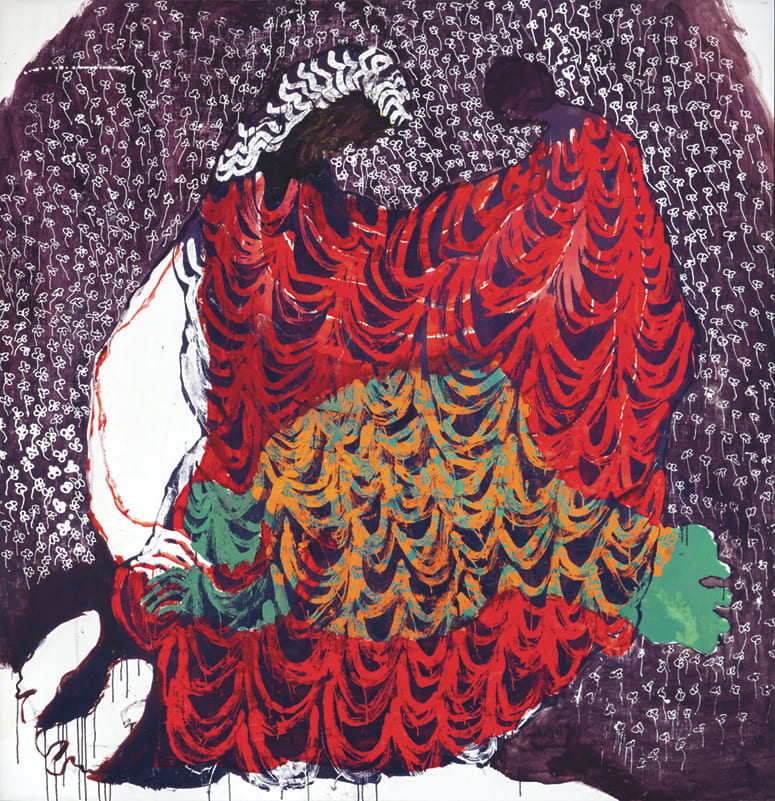

Portia Zvavahera, His Presence, 2013, oil-based printing ink on paper. Courtesy of Stevenson, Amsterdam/Cape Town/Johannesburg

As a lived religion, African tradition deploys through its ritual processes—particularly rites of passage, calendrical rituals, and divinatory practices—tangible material and nonmaterial phenomena to regulate life events and occurrences, in order to ensure communal well-being. African religion supplies knowledge to live by and also a transfer of tradition, worldview, ethical orientation (principles of what is right or wrong), an ontology—a way of life. Hence, the aforementioned rituals are the entry point not only for an understanding of African tradition and religions but also for the visible manifestations and essence of African religious traditions.

As many might know, one type of ritual—initiations for adolescent African girls—causes great consternation among Westerners, because these often involve rites like female circumcision or other bodied practices. Female circumcision is a hotly contested practice condemned by many global organizations and lumped together under the category of “female genital mutilation.” Few have much clarity or knowledge on what is actually involved. Most importantly, the rite itself should not be condemned together with circumcision or female genital mutilation. Whether one agrees or disagrees with the practice, it is important to note that not all female initiations involve circumcision, and that the rituals associated with initiation are crucial to ensuring that an individual’s social position is affirmed by both family and community. For this reason, in many parts of Africa, the communal aspects of such rituals have been retained, due to their salience, while the circumcision practice has been dispensed with altogether, due to the health risks associated with it; this is the case among the Maasai in Kenya and in Somali culture, both in Djibouti and Somalia.

African traditional religions are structured very differently from Western religions in that there is relatively little formal structure. African religions do not rely on a single individual to be a religious leader, but rather depend on an entire community to make the religion work. Priests, priestesses, and diviners are among the authorities who perform religious ceremonies, but the hierarchical structure is often very loose. Depending on the kind of religious activity being performed, different religious authorities can be leaders for specific events. The cosmological structure, however, is much more defined and precise.

African religions are, therefore, a praxis, and this is where the focus of study should mostly be directed. They provide the orientation for the human life journey by defining the rites of passage from life to death. Every life stage is important in African religions, from birth and naming, to betrothal/marriage, elderhood, and eventually death. Each transition has a function within the society. Due to the centrality of ancestral tradition to the African lifeworld, death itself is a significant transition from the current life to the afterlife and marks a continuity in life for those living and those to come. There are rituals that celebrate the passage of time and mark time as it passes for the people, orienting them to the seasonal changes, such as the new yam festival and celebration of the old season and beginning of a new one.

Sacred Kingship and Civil Religion

African spirituality more generally—and Nigerian spirituality in particular—is shaped by how individuals in their daily existence make sense of their interactions with religious experience. In my work, I consider civil religion in Nigeria as a central galvanizing feature that brings together different aspects of religious beingness under the banner of sacred kingship. My earlier scholarship was propelled by the insight that the ideology and rituals of Yoruba sacred kingship are what define Yoruba civil religion and, indeed, the center of Yoruba identity.15 Sociologist Robert Bellah understands civil religion as the sacred principle and central ethic that unites a people, without which societies cannot function.16 Civil religion incorporates common myths, history, values, and symbols that relate to a society’s sense of collective identity. In the case of the Yoruba kings and their people, sacred kingship formed a sacred canopy that sheltered the followers of each of the three major traditions—Islam, Christianity, and African traditional religion—forging bonds of community identity among followers of the different traditions.

Later in my academic life, I explored theoretical issues at the national level, showing how Nigerian civil religion—an invisible faith—provided a template for assessing how we fared at nation building, allowing the symbols of Nigerian nationhood to take on religious significance for the Nigerian public above and beyond any particular cultural communities of faith.17 I do not want to be misunderstood here. Advocating for civil religion in a religiously pluralistic society does not require the erasure of conventional religious traditions. Rather, institutional religion continues to grow in relevance and in the national imagination, whether its invocations are part of conversations concerning nation building, Maitatsine and Boko Haram violence, the secularism debate, the Shar’ia debate, the question of Islamic banking, or the role of the Organization of Islamic Conference. By civil religion, I have in mind not only institutional religion and the beliefs and practices as they relate to the sacred and transcendent, but also practices not always defined as religious, including the rites of passage offered by our various youth brigades, and also the values of communalism and national sacrifice. Religion also encompasses the human, cultural dimensions within faith traditions, such as how human agency shapes, influences, and complicates religious control. Thus, I have argued that religion should be examined not only as a sacred phenomenon, but also as a cultural and human reality, all the while remembering the importance of integrating the sociopolitical dimensions of religiosity into any examination of an African state.

Indigenous religion has always played a pivotal role in the African public sphere, as my study of the Ifa divination system has shown.18 In indigenous religion, communities are governed according to the dictates of the gods, particularly through a divination system such as Fa (Benin) and Ifa (Southwest Nigeria), which encompass the political, social, and economic conditions of life. In my research into Ifa narratives, I showed how, in the Ifa worldview, a traditional banking system was created and made possible when Aje, a Yoruba goddess of wealth, visited Orunmila, god of divination, to seek tips on how to keep robbers from stealing her spurious wealth, for which the added task of securing it was becoming quite burdensome. It was through this encounter that the Yoruba system of banking money in traditional pots kept underground in farms and forests began. What is fascinating about this odu (Ifa text) is that it supports a key and cardinal principle of Ifa tradition—that we seek counsel first, before we perform divination (Imoram la nda ki a to da Ifa). The diviner, therefore, is also a counselor, psychologist, medicine man or woman, and the spiritual guardian of villages and towns.

Ifa defines Yoruba humanity, providing responses to critical issues of its communities.

The Ifa divination system, which produced 256 chapters of oral narratives, constitutes an encyclopedic compendium of knowledge that provides answers to nearly every meaningful human question in the Yoruba and Fon universe. Ifa defines Yoruba humanity, providing responses to critical issues of its communities. Ironically, this pivotal source of knowledge and spiritual edifice—that modern-day Yoruba reject as constituting paganism—is the cornerstone of global Orisa traditions in Brazil, Cuba, and the Caribbean.

Divination enables us to recognize how indigenous traditions have a foundation upon which knowledge and knowledge production is developed. We must be careful not to give the impression that African religious lives are compartmentalized into what is often called the triple heritage (Islam, Christianity, and African traditional religion). In the lived experiences of the people, there has been much borrowing and interchange, particularly in those places that have a history of peaceful coexistence among diverse religious traditions, as is so among the Yoruba. However, African indigenous religion has not only succeeded in domesticating Islam and Christianity; in many instances, it has absorbed aspects of these two other traditions into its cosmology and narrative accounts and practices. A classic example is how the Ifa divination text of the Yoruba provides deep commentary on the practice of Islam by the Yoruba people, such as the hajj tradition. In one particular odu of Ifa, Ifa informs us and, correctly so, that the most cardinal event of the hajj is the climbing of Mount Arafat (Oke Arafa). In response to this verse, Ifa defines its own pilgrimage tradition in the rituals of the climbing of Oke Itase (Ifa Hill), the home of Ifa, when the Araba of Ifa in quiet solitude leads the devotee to the top of the sacred temple of Ifa. As in the Muslim pilgrimage, it is a solemn journey to the hilltop. An Ifa song warns those embarking on the pilgrimage to be pure and those who possess witchcraft not to embark on the pilgrimage.

Gender and the Role of Women

Another false impression often given about African religions is that women do not play any central or leadership roles in the performance of African religious traditions. This is far from the truth. Gender dynamics are important in African indigenous religions and in cultural systems, so much so that women goddesses and women-invented rituals are commonplace. Women constitute a sizable number of the devotees of these traditions, just as they do in Islam and Christianity. One of the more fascinating conversations that has emerged in the debate about African indigenous traditions is about the central role of women as bearers and transmitters of the traditions, and also the negotiation of gender dynamics. Compared to most patriarchal traditions, where women’s participation and roles are curtailed, African religions’ attitude toward gender inclusion is unique. In certain contexts and communities we have many documented instances of the central role of goddesses as founders of traditions, builders of kingdoms, and saviors and defenders of cities and civilizations—for example, Moremi in Yorubaland, Nzinga in Angola, and Osun in West Africa.

Women are revered in African traditions as essential to the cosmic balance of the world. As the late African historian Cheikh Anta Diop argued, matriarchy was embedded in the African way of life. Inasmuch as androcentric authority is more prominent within social structures and systems and patriarchy is more pronounced in the social order, women are considered the cornerstone of the African family system.19 The African mother is a vibrant life force, central to African religious understandings of the interrelatedness between the human and the divine, as she embodies the production and sustaining of life. Thus, many practitioners of African religion, particularly in the shrines of goddesses, are women, indicating the parity with which African religion treats gender and gender-related issues. African American women are turning more and more to goddess religions and Orisa practices, as they find African religion offering them greater religious autonomy than other Western religions.

African Religion in the Creation of African Diasporic Religions

Another crucial aspect to consider in the comparative study of African religions is the reality of the transfer of these religions across the Atlantic through the Middle Passage and transnational migration and cultural exchange. The formation of African diasporic religions in the crucible of forced and voluntary migrations of Africans from the continent from the fifteenth to the nineteenth centuries led to the intermingling of African religions with Christianity and local cultures of the Transatlantic to form novel religious expressions. Religions of the African diaspora are of particular note and importance to the comparative study of African religions because of their resilience and the characteristic formations leading to their performance and expression. Religions such as Candomblé, Vodun, Santeria, and the Caribbean and Orisa tradition historically came about from African transactions with the new world and the old Euro-Christian worldview. Through their mixing, a new kind of religion emerged, forming the basis for what we have come to know as African diaspora religion.

Portia Zvavahera, Cosmic Prayer, 2019, oil-based printing ink and oil bar on canvas. Courtesy Of Stevenson, Amsterdam/Cape Town/Johannesburg

Why is this important to our understanding of African indigenous religions? Because it enables us to theorize questions of syncretism and hybridization and, more importantly, raises the issue of why African religion is flowering and spreading in the Americas, especially in the United States, while it is declining in Africa—a phenomenon that we need to understand. On the continent early modernizers assumed that African religion was part of the problem of the antimodernity project and that uprooting African indigenous religion would auger well for the modern African state. However, in the new world, we are seeing that the stone that the builders had rejected has become the cornerstone and central pillar: for example, Santeria was central to Cuban state making, and in Brazil only recently has Pentecostalism become responsible for the violence against Candomblé devotees.

African scholars in the United States are paying increasing attention to African images in African American culture and religion.20 Some scholars, especially literary critics, now scout African American novels such as Toni Morrison’s and Alice Walker’s works, for glimpses of African traditions. Similarly, there are others like Henry Louis Gates who has appropriated images of the Yoruba deity of Esu in his own work. Significant as these studies are, there seems to be no systematic exploration of African traditions in African American culture.21

African Religion and Interreligious Engagement and Research

Understanding the contours of traditions as they are today consists of picturing both what they are and what they can be against the backdrop of what they once were. Religious contexts are shaped and determined by the identity of these religions. Representation matters, and as scholars we have a responsibility to advocate for religions in their contexts. In the primordial era, various forms of ethnic indigenous religions spread across the African continent, providing cohesive foundations of nations, peoples, and religious worldviews. Based on sacred narratives, these traditions espoused their unique worldviews, defining cosmologies, ritual practices, sociopolitical frameworks, and ethical standards, as well as social and personal identity. Yet in the scholarship on the history of religions, indigenous African religions were never considered a substantive part of the world’s religious traditions, because they failed to fulfill certain criteria defined by axial age “civilization.” Privileged European scholars denied the agency of African religions and singled out—and thereby controlled—African identity. For example, James George Frazer (1854–1941) and Edward B. Tylor (1832–1917) classified indigenous religious practices of “natives” not as universally religious or generative of religious cultures but as forms of “primitive” religion or magic arising from the “lower” of three stages of human progress. These stages characterized European perceptions of human evolution. Such scholars stereotyped African religion—and African peoples themselves—as primitive social forms, part of a lower social order.

Indigenous traditions . . . creatively domesticated the new faiths, absorbing new rituals and tenets into their own belief systems.

Responding to this erasure of African indigenous religion as a productive and generative practice, scholars rallied in opposition. Bolaji Idowu, John Mbiti, Wande Abimbola, Benjamin Ray, Gabriel Setiloane, Laura Grillo, Aloysius Lugira, Kofi Asare Opoku, Emefie Ikenga-Metuh, Charles Long, and others attempted to imbue African traditions with the vitality, status, and identity that is now finally recognized. African religions command their own cultural ingenuity, integral logic, and authoritative force. This corrective scholarship and critical intervention helped to redefine African worldviews and spirituality and, as such, showed how African religion is pivotal to the individual and communal existence of the people. Just as Muslim traders and sojourners introduced new world religions to North and West Africa, Western traders and missionaries introduced new world religions to the continent. Indigenous traditions, however, did not capitulate to these forms, but, rather, creatively domesticated the new faiths, absorbing new rituals and tenets into their own belief systems and responding to the exogenous modernity in its wake.

Space constraints permit me to cite only one example. When I was in Israel a few years ago, I stayed in a modest bed-and-breakfast inn near the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. I ran into a co-resident, a famous Swiss author. When he heard that I came from Nigeria, he wanted to display his knowledge of Ocha tradition as a devotee of Oxhosi, God of Thunder in Afro-Brazilian heritage. When I told him I am a twin (Ibeji) in Yoruba tradition—and in principle a sacred being myself—he almost fell on the floor to pay homage! My credentials as a Harvard professor made little impression on him. Our parting a week later was hard for him! A proper ongoing study of Ifa in West Africa would enable us to understand how one group—the Yoruba of West Africa—encounters transcendence and the sacred in practicing their tradition in ways radically different from Western constructions of religion.

Through a profound process of orality, Ifa as an interpretive tradition espouses an epistemology, metaphysics, morality, and a set of ethical principles and political ideology. These elements are worth exploring and espousing. The first encounters are fascinating. Africans engaged Western enlightenment and religious traditions in serious dialogue and conversation, and responded by creating and interpreting their own modernity. While some Christian mission historians, such as J. D. Y. Peel, for example, correctly argue that the Yoruba had their own enlightenment (“Olaju”), this is always presented in the context of Christian conversion and is very much tied to the escalating Christian missionary movement. But Ifa divination predates Western modernity. Ifa’s religious thought system—friendlier to Islam than to Christianity—not only predates Islam but also engages Islam in serious conversation. One of my favorite Ifa narratives acknowledges to Yoruba Muslims that climbing Mount Arafat was the most significant act of the hajj. The stoning of the devil in the Ka’ba in Mecca was a disguise for rejecting the local Esu, the Yoruba god of fate and messenger of the gods. Esu was represented as a stone mound in the front yard of ancient Yoruba compounds. Ifa rejects the religious extremism of certain forms of radical Islam making life unbearable in today’s world. Many centuries ago, Ifa must have envisaged the possibility of Boko Haram’s Islamic extremist movement ravaging Nigeria today.

On the other hand, the Yoruba people encountered Europeans in dialogue rather than monologue. Similar to other West African communities, the Yoruba did not reject Western modernity but challenged its claim to ontological and epistemological superiority. During the era of Western religious and cultural encounters in Yorubaland, some children were named Oguntoyibo, signifying “Ogun (god of war and iron) is as powerful as the European god.” Some children received names such as Ifatoyinbo, “Ifa is as powerful as the white man’s god.” Such names and concepts illustrate the force and creative resistance of indigenous thought and its ability to engage Western modernity in rigorous debate. It is incorrect to assume that conversion to Islam or to Christianity dealt a deathblow to indigenous traditions. Despite conversion to Islam or to Christianity, Africans continue to accommodate an indigenous worldview that occupies a vital space in the African consciousness.

What is the implication of indigenous hermeneutics for scholars today? I suggest that, at the conceptual and theoretical levels, we begin to take this interpretive approach seriously. What, for example, is the notion of history and the sacred in Akan thought? And why should our work in critical theory not begin from indigenous hermeneutics before we invoke Martin Heidegger, Michel Foucault, or Jürgen Habermas as platforms for interpreting our own worldview and society? European theorists are important, and we need to know and understand them to engage in serious global cultural dialogue, but this does not mean that we should discard our traditions as noninterpretive traditions limited merely to ethnographic illustrations. They certainly represent interpretive traditions, and, when carefully studied, they form a solid foundation for theoretical frameworks used to study and decode these religions in our scholarship.

Notes:

- John Mbiti, African Religions and Philosophy (Heinemann, 1969), 1.

- E. Bolaji Idowu, African Traditional Religion: A Definition (Orbis Books, 1973).

- Ambrose Moyo, “Religion in Africa,” in Understanding Contemporary Africa, ed. Donald Gordon and April Gordon (Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2001), 344.

- Vincent B. Khapoya, The African Experience (1994; Routledge, 2012).

- John Mbiti, chap. 7, “The Spirits,” in his Introduction to African Religion, 2nd ed. (Heinemann, 1991), 65–76.

- Khapoya, The African Experience.

- Laurenti Magesa, African Religions: The Moral Traditions of Abundant Life (Orbis Books, 1997).

- John Mbiti, African Religions and Philosophy, 2nd rev ed. (Heinemann, 1990), 2.

- One must resist the structuralist temptation that views myths as static, unchanging, and simply the productions of a peoples’ imagination about the cosmic order. See Luc De Heusch, “What Shall We Do with the Drunken King?,” Africa: Journal of the International African Institute 45, no. 4 (1975): 363–72, esp. 364.

- V. Y. Mudimbe, The Invention of Africa: Gnosis, Philosophy, and the Order of Knowledge (Indiana University Press, 1998), 250.

- Unlike the Christian community, recited stories of creation are not performed by a single God, who ordered, by fiat, the creation of the universe with mere spoken words. Some biblical cosmological narratives have parallels in African cosmogony, for example, when the Supreme Being summons the hosts of heaven and declares to them, “Come let us make man in our own image.” This same script appears in the creation of the Yoruba world, when Olodumare designates to the Orisa (deities), the job of creating the universe.

- John Middleton, Encyclopedia of Africa South of the Sahara (Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1997).

- Jacob K. Olupona, African Religions: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, 2014), 4.

- Ibid., 56.

- Jacob K. Olupona, Kingship, Religion, and Rituals in a Nigerian Community: A Phenomenological Study of Ondo Yoruba Festivals (Almqvist & Wiksell, 1991).

- Robert N. Bellah, “Civil Religion in America,” Daedalus 134, no. 4 (2005): 40–55.

- Jacob K. Olupona, City of 201 Gods: Ilé-Ifè in Time, Space, and the Imagination (University of California Press, 2011).

- Jacob K. Olupona, “Odun Ifa: Ifa Festival and Insight and Artistry in African Divination (review),” Research in African Literatures 34, no. 2 (Summer 2003): 225–29; “Owner of the Day and Regulator of the Universe: Ifa Divination and Healing among the Yoruba of Southwestern Nigeria,” in Divination and Healing: Potent Vision, ed. Michael Winkelman and Philip M. Peek (University of Arizona Press, 2004), 103–17; Òrisà Devotion as World Religion: The Globalization of Yorùbá Religious Culture, ed. Jacob K. Olupona and Terry Rey (University of Wisconsin Press, 2008); and Ifá Divination, Knowledge, Power, and Performance, ed. Jacob K. Olupona and Rowland O. Abiodun (Indiana University Press, 2016).

- Apart from a few instances in West Africa, where women actually ruled as kings, the designation “queen” was not often used in isolation from the position itself (which was defined in male terms).

- E. Franklin Frazier, Black Bourgeoisie: The Book That Brought the Shock of Self-Revelation to Middle-Class Blacks in America (Simon & Schuster, 1957). I was inspired by Andrea Lee’s review of Lawrence Otis, Our Kind of People: Inside America’s Black Upper Class (Harper Collins, 1999), published in The New York Times Book Review, February 21, 1999.

- My essay “Omọ Òpìtańdìran, an Africanist Griot: Toni Morrison and African Epistemology, Myths, and Literary Culture,” in Goodness and the Literary Imagination, ed. Davíd Carrasco, Stephanie Paulsell, and Mara Willard (University of Virginia Press, 2019), is an attempt to begin a fresh conversation on this topic.

Jacob K. Olupona is Professor of African Religious Traditions at Harvard Divinity School and Professor of African and African American Studies in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences at Harvard University. His many publications include African Religions: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, 2014);

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.

I really love this, it’s helps alot

The presentation was insightful. it is only the Africans that can present the issues of Africa in the African way. Thank you

This was amazingly written. Truly opening my eyes on traditions, cultures and rituals that I did not know existed.

Thank you for this interesting essay on African religion.