Perspective

Resolution 2009: Get New Eyes

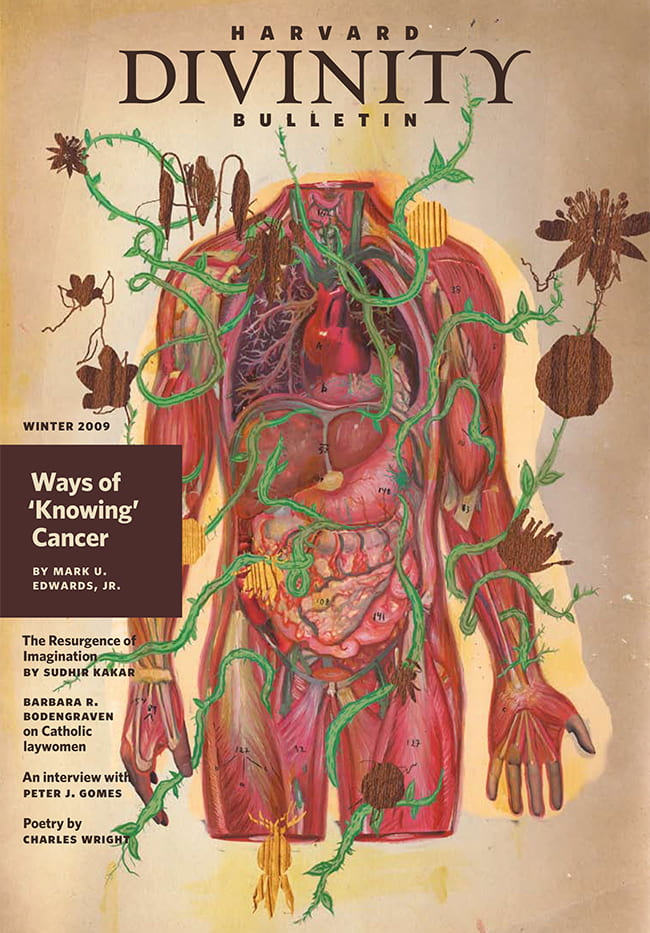

Cover illustration by Erik Sandberg. Cover design by Point Five Design.

By Brin Stevens

I was pregnant for most of 2008. it was a good year to give birth, for I was certain the sheer enormity of faith in possibilities that made this a landmark year would entrain the little soul in my womb. I would look back on this year, telling my daughters the story of how, in a cramped voting booth, I placed one hand on my bulging third-trimester belly and the other hand on the hand of my eldest daughter and we filled in a tiny bubble. That same day, a few states away, my aunt was trying to ease the pain of her stage IV endometrial cancer. She would succumb to her disease in this momentous year, never knowing how the political story ended.

While we were aware that many of us were focused on the United States primaries and election of 2008, we decided not to solicit feature articles for this issue that were explicitly political—though we have included Dialogue pieces by Peter Paris and David Lamberth that address the new possibilities engendered by the past year, as well as the continued challenges we face as a nation. Instead, we felt it was important to run three feature articles that address issues and struggles longer and more global in scope.

When I initially met with Mark Edwards, we had no plans to talk about cancer. I was there to discuss another article he was writing for possible publication in the Bulletin. But as conversations go, the professional settled into a comfortable personal, and he began to tell me about a chapter he was writing on living with multiple myeloma. I was taken aback by his clearheaded profundity in the face of such uncertainty. I wanted to read his manuscript—and thought Bulletin readers would as well—and intimated as much.

I never received the first article he proposed, but a few weeks after we met, he sent me a longer version of what would become this issue’s lead article.

Many of us read an article with nothing more than the hope that the author will offer a fresh perspective on a certain topic. I rather expected Mark Edwards’s piece on cancer to focus on how illness forces one to engage in a deeper understanding of one’s religious beliefs. But his essay is not a visceral account of his life with cancer. It is an article in which he, a religious scholar, explores his scientific curiosities, while wrestling with his own potential needs as an ill person for “more than what the academy currently offers in all its sciences, natural and social.” His is a pragmatic examination of illness and disease, etiology and philosophy. The depth of his thoughts surely stem from being thrust, not into a new world, but back into the same world with new eyes.

“As a natural process,” he writes, “cancer develops by chance, follows no plan, and cannot be characterized as good or bad, right or wrong, purposive in the teleological sense, or unnatural.” Cancer, as a disease, is part of the evolutionary process. And yet cancer, as an illness, he explains, “is the experience of living through the disease from ‘inside out.’ It attempts to capture the lived experience of one who has the disease. It lives and breathes existential subjectivity.”

Many of us will come to feel the effects of cancer’s intractability, whether lived or intimately observed. And when it arrives, we will set aside everyday conversations, halt what Elaine Scarry calls our system of production—an active participation in chores which keep our minds lightly busy instead of paralyzed by wonder at our existence—and follow into its chaos. It will become our new mirror, as famed oncologist Charles Heidelberger described it, “into which we look and see ourselves.”

We’d like to think that the articles and poetry we select for the Bulletin are all, in their own way, mirrors offering reflection. In Barbara Bodengraven’s essay, “Glimpsing a Land Beyond Limits,” she examines anew the polarization of gender roles in the Roman Catholic Church. In a year when the first African American will reside in a White House built, in part, by slaves, there is a sense of hope that women might one day break through not only the iron gates of 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue to become president, but the sacristies of our Catholic churches to become priests. Just as Barack Obama, as our first biracial, bicultural president represents the diversity of the American population, so, too, should Catholic priests represent both sexes of their congregants.

Bodengraven’s point is clear: “[t]he proliferation of God’s Kingdom has been limited—stymied even—all in the name of preserving tradition.” This tradition, she points out, “just happened to arise from other, earlier humans’ culture and context. Tradition hasn’t always been tradition. It was not revered as tradition at the beginning. It was actually new interpretation at one point in time.”

As psychoanalyst Sudhir Kakar writes in “The Resurgence of Imagination,” he sees a return of the romantic vision to Western culture, as disciplines including social neurosciences and evolutionary psychology have started to emphasize the innate, empathic altruism in human social life. And yet in non-Western societies, either the romantic vision never lost its primacy, or the movement seems headed in an opposite direction. Kakar discusses how those in his own profession, psychiatry, can learn from Hindu and Buddhist practices which develop the connective, empathic imagination. The challenge for us all, he says, is not to go through life as a detached observer, but rather “to be aware of the spiritual movements as we travel through life, to look around and see again with the innocent eye.”

I am reminded daily, through the innocent eyes in my household, of what can happen when we allow ourselves to unfold naturally, and view the world with “new eyes.” In the words of my three-year-old, from one of her favorite Dr. Seuss books by the same title, “Oh the THINKS you can think!”

Brin Stevens is an editor of the Bulletin.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.