Featured

Reclaiming the Rainbow

Daria Donnelly remembered.

By Wendy McDowell

Not long after meeting Daria Donnelly five years ago at our children’s elementary school, I started referring to her as “the source of all good things,” because she always offered just the right suggestion for practically anything you might need. Be it a child’s haircut, a place to bird-watch, or where to get the best fresh mozzarella, she was more than happy to share her font of wisdom, and my family and I were never disappointed when we followed through on her recommendations.

So I was not especially surprised when I discovered that Daria’s professional life involved reviewing children’s books for Commonweal magazine. In her columns, of which I became an ardent reader, and in conversations we had about her work, she made it clear that she took children’s literature extremely seriously. She considered the writing and illustrating of children’s books to be artistic endeavors as worthy of criticism and analysis as any others. One spring day when we were sitting in the park across from the school, she told me how irate she was when she learned that the order of books was going to be changed in a newly published version of C. S. Lewis’s Chronicles of Narnia. While children ran and swung and squealed, she argued clearly and concisely about the moral problems with violating Lewis’s original intentions, and described what a loss this will entail for the children who (unaware) would read them in the revised order.

Even after Daria was diagnosed with multiple myeloma in 2002 and began enduring the “full arsenal” (her term) of treatments for this rare blood cancer, she would keep a stack of children’s books next to her in bed that she—and often her daughter, Josie—would be perusing, as well as books of poetry. She still couldn’t wait to tell you what delightful, or decidedly undelightful, books she had been reading, and nearly always you would leave with a directive to go out and get a certain book that simply must not be missed. (One of her favorites last year was I Am a Pencil, by Sam Swope, in which that well-known author of children’s books writes about his experience teaching poetry writing to children in Queens. I got it. I read it. And as always, Daria, it is a treasure.)

Below, and in following blocks, are excerpts from three Commonweal book reviews by Daria Donnelly who died September 21, 2004, at the age of 45.

I am overprepared to trust the mordant and subversive (but not the ironical) because of my belief that the rise of protective sentimentality in children’s literature correlates with what has recently been called the “last taboo” in children’s books, namely the prejudice against the subject of religion. Apparently, skittish publishing conglomerates fear the wrath of both secular, liberal consumers who think any mention of religion invites indoctrination, and conservative Christians looking for doctrinal offenses everywhere. With William Bennett the most visible purveyor of values and faith for kids, and parents suing states to remove Harry Potter from libraries because it’s satanic, who can blame them?

But I am starting to doubt my instinctive reach for those who gladly offend decorum and piety, and yet fearlessly pose the same big questions religion does. These writers do not present the only way to jump-start our sluggish sense of wonder. Sometimes they are dead wrong: British novelist Phillip Pullman, whose theodicy rage I have alternately praised and questioned in these pages (November 17, 2000), spent the autumn jetting around the United States on a book tour announcing that C. S. Lewis’s Chronicles of Narnia are “ugly and poisonous,” and that Lewis’s Christian vision caused him to write a series that “hates life.” That is inane. Lewis’s series is radiant with the love of this world. The simplest way you know this is that when you read it, you want to eat every single food mentioned: the lumps of butter, the creamy milk, the hot potatoes, even (a medievalist friend adds), the dirt that the trees enjoy. —April 6, 2001

Nowhere was her passion for children’s literature more evident than in her conversations with children themselves. To eavesdrop on Daria talking to the children at school about what they were reading, you’d swear it was a grad-school discussion you were hearing and not a grade-school one. She would engage in long talks with kids of all ages about the intricacies of the plot in The Wind in the Willows or the development of the characters in the Harry Potter books, and the kids would start to glow when they talked to her. That’s because Daria truly listened to children, her own (Leo, now 10, and Josie, now 3) and everyone else’s, and even shared their opinions in her columns, calling them her “test readers.” Meanwhile, she was so lively and funny that kids were none the wiser that she was schooling them in how to think and talk about literature at a deeper level (Daria had a PhD in literature from Brandeis University, and had taught poetry and literature at the university level).

Toward the end of Daria’s illness, we went over to her house for a visit and I was worried that it might be too tiring for her in her jaundiced, weakened state. If it was, she never let on, because she was too busy cheerfully engaging in a conversation with my daughter, Isabel, about why George was their favorite character in the Nancy Drew books (“She’s the competent female character, isn’t she?” Daria declared).

Isabel and I were lucky to be provided with our own personal book recommendations from Daria, many of which we read together at bedtime. Although it is hard to choose a favorite, we agree that Marianne Dreams by Catherine Storr takes the prize. Written in 1958, it is a haunting and poignant story of a sick young girl forced to convalesce in bed for several weeks. To counter her boredom, Marianne starts to make drawings with her grandmother’s pencil—a house with a boy at the window—and finds herself transported into her own picture in her dreams. She encounters a seriously ill young boy named Mark, whom she has heard about from her tutor, and they must journey together through danger to get to the sea, a place of freedom and safety.

Although we have read many classic and beautiful books together, this was the only one that made my child (a natural night owl) push back her bedtime so we could have more time to read. She chose it for one of her fourth-grade book projects, and acted out the part of Marianne for her classmates. The book has stayed with me as well. And because its themes include the cabin fever experienced by anyone with a prolonged illness (illness itself provoking a dreamlike existence), the transformative power of art, and the healing power of friendship, I can’t help but associate Marianne Dreams with Daria.

But then, Daria would understand. The way a book can become tied in your life to a certain time or a specific person is just the kind of phenomenon she relished thinking and writing about. That is why, in addition to writing about her, I thought the best way to honor Daria would be to reprint some of her own words, because she always had interesting and profound (and brave) things to say in her columns. Besides, I’m not the only one who thought her writing about children’s literature was among the smartest out there, and who believed that her work was all the more important because she was never afraid to address thorny issues or so-called difficult books (case in point, Daria’s October 24, 2003, interview in Commonweal with the novelist and fantasy writer Gregory Maguire, entitled “A Gay Parent Looks at His Church”).

As her husband, Steve Weissburg, puts it: “Keep in mind that Daria was totally anti-sentimental. She hated that ‘baby Jesus come and squeeze us’ kind of stuff. She liked the macabre and the nasty in books, because she believed that allowed kids to let the fears they must have come out in a safe place.”

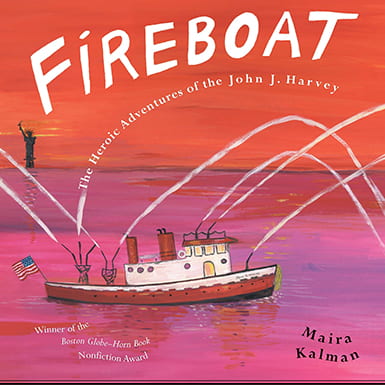

Tough subjects, small people. Is it possible to make a great picture book about September 11? Maira Kalman, veteran New Yorker artist, has done it. Her Fireboat: The Heroic Adventures of the John J. Harvey is based on the true story of the Harvey, a retired New York City fireboat that had been saved from the scrap heap by an association of friends. When those friends heard that planes had crashed into New York’s tallest buildings, they jumped onto the Harvey and rushed to the site. The hydrants west of the World Trade Center were defunct. For four days, the Harvey, manned by these improvising amateurs under the direction of her retired NYFD Captain Bob Lenney, pumped inferno-fighting water from the river.

Why does the book work? Because Kalman eschews the genre of tragedy for something more familiar to children. Think of The Little Engine That Could and The Velveteen Rabbit. Children champion objects others think they have outgrown. One of my young test readers said she liked this book because it was “funny.” I think she meant joyful, because something, even on that horrific day, is rescued. —April 11, 2003

In one of her reflective moments, Daria told me that she wanted her work, and her life, to be focused on “beauty and truth.” She was not afraid of lofty goals, but she also happens to be one of the few people I’ve met who actually attained them by virtue of her sheer generosity and integrity. While others wax on about “building community,” Daria simply went about doing it, introducing her wide and varied groups of friends and contacts to each other and enabling us to be a re-source for each other. The first time she went into the hospital for a stem cell transplant, she set up a “music night” at her house after she was gone so a handful of us could get together and play. Even at the visiting hours after she died, her husband was searching the room at the funeral home to find two mutual friends that Daria had insisted absolutely must be introduced to each other.

Daria was deeply religious and sharply intellectual at the same time (contrary to simplistic red state vs. blue state analysis, this is possible!). Indeed, she believed that faith and reason serve to deepen each other. “Daria embodied the very best of the Catholic tradition,” said her sister Betty Anne Donnelly (Harvard Divinity School MTS ’85). “She helped run a Catholic Worker House for battered women in Rochester, and a community writing project for high school students in South Boston. She was a charismatic teacher at Boston University, and a longtime activist in the ecumenical anti-hunger group Bread for the World. She studied Jewish-Christian relations in Jerusalem, and was committed to interfaith dialogue. Daria was a devoted reader of the great mystics, and a keen and irreverent commentator on the sacred and secular alike. She was the very best sister, daughter, mother, wife, and friend, and we miss her with an awful hunger for her company.”

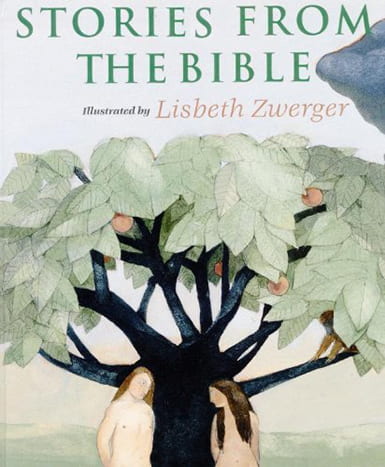

Here’s the assignment: Read the story of Cain and Abel (King James version please). With the text reprinted on lovely thick stock, draw one marginal illustration.

Here’s what you probably will not draw: Two young men seated facing each other, one stroking a goat, the other cradling a bowl of fruit. Their gaze is cast downward, their costume nineteenth-century rural romantic. An immense quiet surrounds them. This is the moment before the cruelty and shame of the story itself: two brothers sitting together as they must have done for days and years before the story.

That drawing and angle of vision are the particular genius of Lisbeth Zwerger, one of the great living children’s book artists. She has just brought out an illustrated bible, Stories from the Bible, that, no exaggeration, will change the way you read the book.

For a month I have been sitting with Stories from the Bible thinking about why it is so beautiful and true. Zwerger bases illustrative choices on her regard for poetic knowledge or what might be called the wisdom of images, and that makes all the difference. —April 19, 2002

On the day of Daria’s funeral, a rainbow suddenly appeared in the sky above her brother’s house in Belmont, where her family and friends had gathered to share their grief. Everyone came outside to stare up at it. It was a startling vision because there had not been a drop or even a hint of rain all day. What’s more, it was not an ordinary looking rainbow—it was reversed and off-kilter—giving it a shape that could best be described as a side-ways smile.

Although it has been Hallmarkified (and, in this country, politicized), the rainbow is a symbol with deep meaning and resonance in religious and mythic traditions across the world. In Jewish tradition, it is the sign of God’s covenant with human beings after the flood, and rabbinical midrash link it to the light of Hanukkah (one midrash I read said the rainbow “is like the divine image”). It is traditional for Jews to say a blessing when they see a rainbow, acknowledging its symbolic significance. In Christian tradition, the rainbow has come to be associated with the crown on Christ’s head, the fulfillment of the promise of resurrection, and the seven colors are said to coincide with the seven virtues. And I read somewhere that the rain-bow could well be seen as the “symbol of imagination itself,” which seems especially fitting for Daria, who was such a great lover of imagination.

Of course, in keeping with her anti-sentimental nature, Daria would probably remind us that for all the rainbow’s symbolism of hope, the rainbow covenant wouldn’t have been necessary if it wasn’t for God’s awareness that we humans work against it. We mess up, we fall short, and we must never be afraid to own up, especially to those closest to us.

I am certain that Daria was responsible for that rainbow. After all, the day before she died, her sister, Betty Anne, had asked her to send a sign as a consolation for Leo and Josie (Daria had rolled her eyes and said, “All right, I’ll do it, because I think God has a sense of humor!”). Who else would provide such a whimsical sign, yet one infused with interfaith meaning? Who but Daria would send a sign that both adults and children could understand, something straight out of a children’s book, just the kind of rainbow that her favorite illustrator, Lisbeth Zwerger, might draw?

By far, the most evocative image I came across in researching rainbow symbolism originated with the ancient Incas, who believed that the rainbow carries heroes between heaven and earth. Daria was one of my heroes. When I miss her, which is often, I like to imagine her crossing the rainbow bridge, our “source of all good things,” returning to the ultimate source of all good things.

Daria, At Large

From a column by Daria Donnelly in Commonweal on April 25, 2003.

On Ash Wednesday 2002, I was diagnosed with multiple myeloma, a rare blood cancer that weakens the immune system and eats the bones. The chaplain put ashes on my head and said, “Remember you are dust. . . .” Talk about the ring of truth. At forty-three, and six months post-partum, I had two broken ribs, two, possibly three, crushed vertebrae, severe osteoporosis of the spine, and a pelvis so weak that I was losing my ability to walk. Sternum damage precluded lying flat in bed. I was swiftly returning unto dust.

Fortunately, treatment came even more swiftly. That Friday I had a bone-building infusion and the first of many other life-saving pills, injections, and chemotherapies. Though researchers have not yet found a cure for myeloma, it responds to an ever-in-creasing array of treatments. Still, I won’t kid you: people do die from multiple myeloma, everywhere, still.

It has taken a year to draft this notice of my illness, and announce my new roles at Commonweal. That’s testimony to how absorbing ill-ness and healing are—and to how reticent I feel in light of the whole genre of illness writing. My getting sick increased my attention to the everyday heroism of refugees, the depressed, the arthritic, the mourning, the lonely, all those who know how good it is to get through a day. It also wakened my shamefully rusty sense of the centrality to the gospel of mercy and healing and (at her best) to the church. . . .

Illness, like conversion, does not change personality. (I’m still cheerful, and still slovenly at my desk.) It does change energies and horizons. The therapies I am still undergoing are demanding, both of energy and of time. Fortunately this is less so as I get better: I’m now a vigorous and newly curly-haired woman with a cane, and that’s mostly because it beats wearing a “Fragile” sign. Thanks to a tri-weekly infusion, my bones are much improved, but they won’t be regularly riding the Boston-to-New York Acela train anytime soon.

Even with the limitations and distractions, I am able and want to be part of the great work that is Commonweal. Thus, I am At Large. Translation: I do what I can, when I can. I love the title. It makes me seem out and about, maybe even hard to find. A flattering fiction, as, in truth, I do a good imitation of Emily Dickinson. Stay put. Travel by other means.

Wendy McDowell is an associate editor at the Bulletin.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.