Dialogue

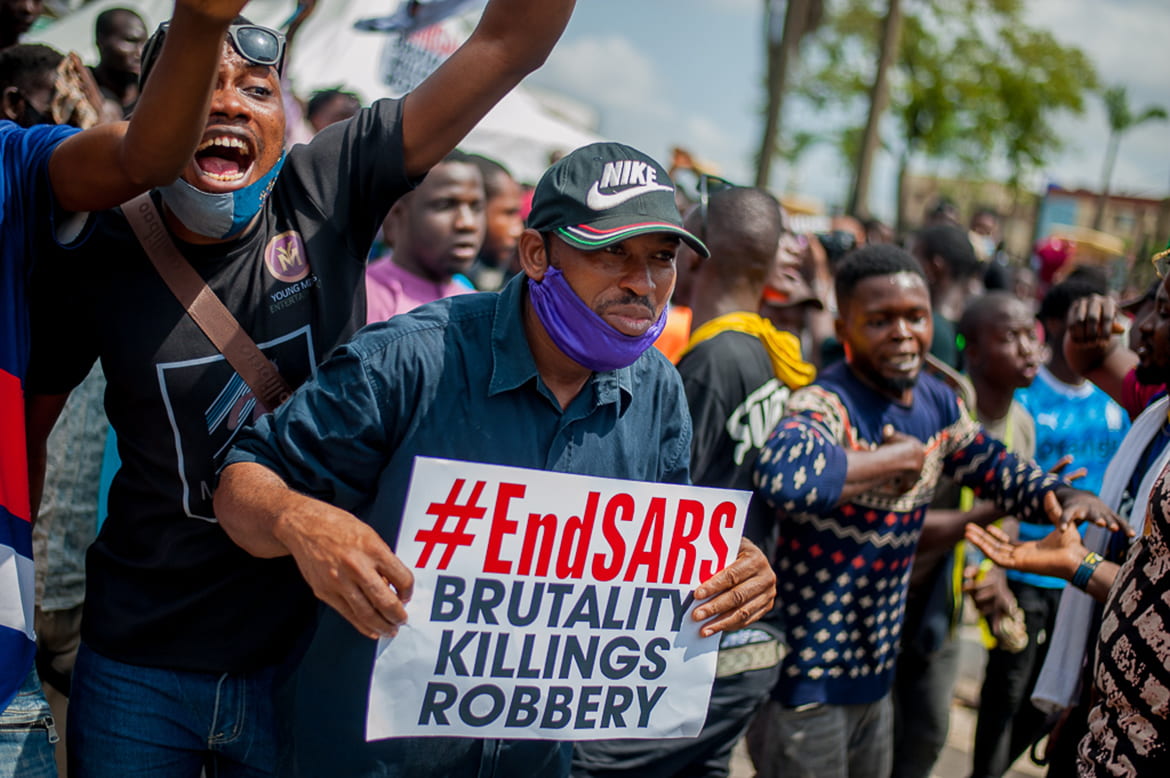

Police Brutality and the #EndSARS Movement in Nigeria

By Oluwole Ojewale

In Nigeria, our policing institution is rooted in command and control, a model handed over to us by our colonial masters, the Western countries that came to colonize Africa. Rather than having a policing system that renders service to the general public, we have a policing system that was established to serve and carry out the directives of the governing elites. Over the span of 60 years, this policing system has not really reformed itself. It still operates based on the template of the Nigeria Police Act that was put in place in 1943. The establishment of the defunct Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS) of the Nigeria Police Force drew from the command and control template of the 1943 Police Act. This unit was originally put in place to combat armed robbery, but over the years, it has become an instrument of subjugation and harassment and intimidation, particularly against the youth. The federal government has claimed that they will reform the police, and SARS in particular, but little has changed.

In October 2020, Nigerian youth took to the streets to protest against police brutality in what became the #EndSARS movement. This movement resonated across the world, in the United States of America, in Europe, and in Asia, driven by Nigerians in the diaspora. The #EndSARS movement emerged not only in response to police brutality. It arose from a combination of factors. Youths have been largely marginalized and politically excluded. While they can vote, they are rarely appointed to important political positions. These youths see the governance challenges in Nigeria and want to create change.

The protest calling for the ban of SARS extended beyond issues of human rights violations by the police. It was a larger call for improvement in governance in Nigeria. With the wave of protests against the police, people are saying: We have had enough of this maladministration. We have had enough of this poor governance from the state. And they are actually protesting against the state. Whenever citizens can no longer stand issues of police brutality, what they are saying, in effect, is Enough of this bad governance. We’ve seen this in movements across the world that have risen against police brutality—they are actually protesting against the state. The police institution is just a precursor to that. The police force is the symbol of state authority. The primary responsibility of government is maintenance of law and order, and the police is the institution tasked with the enforcement of law and order in countries around the world.

What police brutality means to an average American citizen, though, is different from what it means to an average African. In the United States, police brutality and subjugation goes along racial lines of Black and white. But in Africa, it’s a matter of a Black police officer oppressing a fellow Black African in Africa. If a Black American citizen is protesting against police brutality in the United States, that protest is undergirded by how the right-wing element, white supremacists, are using policing as a tool to subjugate Black Americans.

In Nigeria, we have Black police officers who have been trained in the ethos and philosophy of colonial policing, which was rooted in subjugation and wanton human rights abuses. After 60 years of independence, we have not been able to shed the legacies of the policing institution, the code of conduct, the philosophy that the colonial masters who came to Africa handed to us. We still have the police institutions that our colonizers built on this culture of subjugation, and these institutions have not reflected the required police reforms that we want to see.

In Nigeria, then, we experience police brutality. But this scourge does not go along racial lines, as it does in the United States. Instead, it is a case of politicians who were elected by community people, by citizens who get into power and then employ police officers who go about oppressing the general public. This becomes a cycle of violence: an average Black person in Nigeria sees the act of wearing a police uniform, holding a gun, holding a baton, and all these other instruments that the police use in carrying out their law enforcement duty as a tool of oppression against a fellow Black person.

The militarization of the police has extended across all facets of governance and facets of our human lives to the extent that elections, which are supposed to be civil affairs, have become so militarized that whenever any election is held, the military services are deployed. All of the relevant law enforcement institutions are also deployed. And as elections degenerate into war, ammunition is deployed just for the basic exercise of franchise, which is the right to vote and to be voted for.

This also extends to public life for politicians. Poor communities in Nigeria are poorly policed. All politicians move around with retinues of police officers who are protecting them and their families. Politicians feel that anywhere they go, they must show that they have the police power to subjugate all other members of the community—wherever they go, they must show that they are in charge. The true taste of power, for a politician, is the ability to control and command the police. The institution of policing has itself become the tool of politicians who want to win elections and subvert the electoral process. In order to access and sustain political power, a person must be in charge of the police. The police force thus becomes an instrument for rigging elections, fomenting violence during the election, and perpetrating all sorts of atrocities.

The global militarization of the police is a fear that plagues every nation. But there is a clear difference between what an American citizen is experiencing and what we experience in Africa. In the United States, policing is enmeshed with white supremacy, whereas in Nigeria or in any other African country, it is a matter of fellow Black African police officers using the tool of the policing institution to oppress their fellow Black people. We must be cognizant of the peculiarities of our cultural and historical contexts in addressing police reform if we are to position the police as a service-oriented agency rather than as a military institution.

Oluwole Ojewale is a scholar and program management expert at the Institute for Security Studies. His research and advocacy campaigns span transnational organized crime, election policing, security governance, and violent conflict in West and Central Africa. His most recent book (with Adegbola Ojo) is Urbanisation and Crime in Nigeria (Palgrave MacMillan, 2019).

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.

Thanks for your scholarly thoughts. Policing shouldn’t be used as tool for oppression as we see in Africa especially Nigeria. Virtually, you can’t see a day without reporting a police brutality. The authoritarian governments given them unnecessary power to dealt with opposition/ or voices criticised the action and inaction of governments. If those in power could see themselves as servant and not ruler, there will be a better police institution to maintain law and order without brutality.