In Review

Perfect Machines, Avenging Angels

The New Sci Fi: Battlestar Galactica and The Sarah Connor Chronicles.

By Brett Grainger

When I was growing up in the late 1970s, boys belonged to one of two tribes: you were either a Star Wars geek or a Star Trek geek. We may have seemed a mass of miscued passion, but important differences divided the disciples of James Tiberius Kirk and Luke Skywalker. The biggest difference may have been their respective visions of the future. Star Trek was fundamentally optimistic. It radiated a faith in rationality, human nature, and secularization. Each week, the crew of the USS Enterprise faced a new test—usually involving an uppity alien civilization—but the challenges felt cursory at best. Any foe who could not be won over by Spock’s soothing Vulcan logic—or Kirk’s animal magnetism—were eventually subdued by photon torpedoes. Trek was the beacon of a progressive millennium, an extension of the enlightenment project into the darkest corners of the universe.

If Star Trek projected the utopian fantasies of the eighteenth century into the mid-twenty-first, Star Wars went neomedieval. The universe, once ruled by an edenic republic, has fallen into the hands of the Galactic Empire, a dictatorship fired by a passion for Teutonic efficiency, papal fashions, and British elocution. While the heroes of Star Trek are clean-cut and organized, in Star Wars, the good guys are hopeless: an undisciplined rabble of petty criminals, prickly princesses, and gay robots. Taking cues from mythology and Eastern mysticism, George Lucas cast his modern fairy tale as an old-school, Manichaean mano a mano, where evil seems always to have the upper hand—especially in the dark heart of the original trilogy, The Empire Strikes Back. Against the crushing superiority of the Empire, the Rebellion can wield only a quaint superstition. But woe to him who underestimates the power of resurgent religion. By returning to the practices of an ancient order of warrior monks, Luke brings down the modern goliath of science and rationality and restores order to the universe. Faith, we’re told, will triumph over disenchantment, but history will have to get a whole lot worse before it gets any better.

The success of Star Wars spawned a wave of imitators, notably Battlestar Galactica, a short-lived television series that debuted in 1978. Battlestar was campier than Star Wars, and shared its revival of interest in religion and mythology. The series creator, Glen A. Larson, a Mormon, infused the show with his private cosmology. In a distant corner of the universe, a ragtag fleet of ships flees annihilation at the hands of a race of robots known as Cylons. The humans, survivors of the 12 Colonies, embark on a quest for Earth, the fabled “13th Colony.” Swap the spaceships for dusty stagecoaches wending their way to Utah, and the parallels with nineteenth-century Mormon history were patent. Even so, Larson wielded theology mostly as a mythological frame for conventional action stories. Rarely was religion used to advance a storyline or explain the motivations of characters: it was a fanciful special effect, peripheral to the “real” work of warriors and politicians.

Battlestar Galactica is the paradigm for a gritty, realistic school of science fiction that puts social drama before melodrama, currency before camp. Sci Fi Channel.

When the Sci Fi Channel relaunched Battlestar Galactica in 2004, the show differed so markedly from the original cult classic that many fans were initially reluctant to get on board. The show’s executive producer, Ronald D. Moore, wanted nothing less than to reinvent sci-fi. Gone were the fey, swashbuckling heroes and grimacing, becaped villains. Battlestar Galactica would be the paradigm for a gritty, realistic school of science fiction that put social drama before melodrama, currency before camp. If the Enterprise was an Apple, the Galactica is a PC. The bridge resembles the control room of a submarine: a cramped, windowless bunker with hardwired telephones and crappy intercoms. Warships trade bullets and old-fashioned nukes, rather than fancy photon torpedoes, and battle sequences are captured in a raw, handheld documentary style with muted sound effects (there is no sound in outer space).

The biggest upgrade Moore introduced involves the Cylons and the motivation behind their genocidal fascination with humanity. Cribbing from Blade Runner, Ridley Scott’s dystopic 1982 masterpiece, Moore creates a backstory in which the Cylons, created as a slave class, gain consciousness and turn on their creators. Over time, the robots evolve, shedding their metal exoskeletons until they are virtually indistinguishable from humans. Freed from the vicissitudes of mortality (when Cylons die, a “resurrection ship” downloads their memories and consciousness into a new shell), the Cylons become prey to another human weakness: angst. While the human “colonists” vacillate between skepticism and polytheism (modeled on the gods of ancient Rome), the “toasters” (an anti-Cylon slur) find ultimate meaning in a stern monotheism. Perfect faith demands perfect disciples: a race of supermen bred to breath his perfect will. Humanity, saith the Cylon God, has fallen short and deserves righteous wrath for its manifold sins. In other words, the toasters are fundamentalists.

However comforting it may be for liberals to imagine Pat Robertson as a machine- like automaton shorn of free will and empathy, such fables do little to get at the deeper motivations behind militant faith. Fortunately, the writers of Galactica are continually complicating characters and storylines in ways that force viewers to switch sympathies. For one thing, Cylons and humans have interbred, making it more difficult to sort out the wheat from the chaff. In the third season, a number of Cylons defect to the humans who, in predictable fashion, turn the ship into Battlestar Guantanamo. Earlier this year, as the show entered its fourth and final season, it became clear that this series was unlikely to have a conventional science-fiction ending, where humanity wipes out all the killer robots. In the world of Battlestar Galactica, heroes and villains are fluid categories, a moral palate untapped by most science fiction of the cold war era. No doubt, this change reflects the ambiguities of our age, not to mention an exhaustion with the “cosmic warfare” school of international relations pursued under the administrations of George W. Bush. The more progress the humans make in their war on Cylon terror, the more they realize they must find some way of living with the enemies they have made.

No science-fiction property defined the killer robot storyline as effectively as James Cameron’s The Terminator. Though the formula felt fresh in 1984, the film was essentially a retread of Mary Shelley’s gothic masterpiece Frankenstein. In creating the novel that many consider to be the mother of science fiction, Shelley robbed the graves of European mythology—notably the Jewish golem and homunculus tales—stitching the monstrous limbs into a romantic caveat against the dangers of unchecked ambition. The “Creature” became a vessel for our hopes and fears about modernity, in particular the Promethean forces unleashed by science and the Industrial Revolution. It is a short, dark road from Bella Lugosi’s lumbering monster to Arnold Schwarzenegger’s efficient Austrian cyborg.

For the 1991 sequel to The Terminator, James Cameron flipped the concept on its head. Monster becomes bodyguard: when the machines send an advanced model to terminate John Connor, the future Connor hacks an obsolete Terminator and sends it back in time to shadow his mother and younger self. The effect was thrilling, allowing audiences to root for the projection of their fears. But even if Arnold was working for the good guys, his actions carried no moral weight: he was just executing his programming. In Terminator 3: Rise of the Machines, this determinism was extended to the human characters as well. After John Connor does everything he’s been told will avert “Judgment Day”—when a network of military computers goes rogue and launches a nuclear strike on the human race—he discovers that his efforts have unwittingly helped to usher in the inevitable. Not even a future savior of the world can operate outside the designs of Fate.

Like the reimagined Battlestar Galactica, the Terminator trilogy (a fourth film in the series, Terminator Salvation, will be released in 2009) is strewn with more religious references than smoldering cars. Similarly, the films are metaphysically indebted to Christian fundamentalism. The apocalyptic worldview of The Terminator is a secular mirror to “Left Behind,” the bestselling Christian science-fiction novels by Tim LaHaye that have sold 50 million copies and spawned a film trilogy of their own. The future civil war between machines and humans has an uncanny resemblance to what fundamentalists call the Tribulation, a seven-year period of chaos following the “rapture,” in which unbelievers will battle an enemy who can’t be killed (as one oft-noted passage from Revelation puts it, one of the beasts will recover from a “fatal wound.”) There’s Sarah Connor, the slightly feral Madonna with a MAC-10 who chats about Judgment Day with the certainty and specificity of John Hagee. When Arnold, clad in leather chaps and sunglasses, swings his hyperalloy combat chassis onto a stolen Harley Davidson, what else should we take him for but a dark horseman of the apocalypse?

Yet, for all the dime-store allegory, religion in The Terminator was really nothing more than an armature on which to hang a bunch of explosive set-pieces. That’s fine for a two-hour movie; but in TV, where story arcs can last for 20 episodes or more, blowing stuff up will only get you so far. So when James Cameron decided to produce a televised version of the franchise, Terminator: The Sarah Connor Chronicles, he encouraged his writers to dig deeper. As a result, questions of faith have become central to a number of the show’s main characters, notably an FBI agent named James Ellison. Near the end of the first season, Ellison, who is tracking Sarah Connor and her son, interviews a psychiatrist named Silberman, who once treated Sarah in a mental hospital for her conspiracy theories about “killer robots from the future.” After witnessing Connor’s killer robot firsthand, Silberman holes up in a log cabin to read his Bible and await the End Times. Silberman, who suspects Ellison of being “one of them,” drugs the agent and ties him to a chair. When Ellison wakes up, Silberman asks Ellison, an African American, if he’s a “man of the book.”

Silberman: Tell me, agent, do you believe in the apocalypse?

Ellison: I’ve read Revelation.

Silberman: Could it be that the apocalypse in the book and the predictions of Sarah Connor are one and the same?

Like Silberman, Ellison has seen, and wants to believe. But Silberman isn’t convinced that Ellison is working for good, so he lights his log cabin on fire and leaves the agent to die. Sarah Connor comes to the rescue, and the final scene of the episode shows Ellison in a Bible study, having finally come round to the obvious: that what the Bible says about the future is literally true.

Christian fundamentalists have often been accused of cribbing from secular culture, stealing its best ideas and repackaging them to peddle their own distinctive “biblical worldview.” Even science fiction, once derided as “devilish” and “worldly,” has become an arm of fundamentalist apologetics. But the flow of cultural influence is never one way. When the plot of a mainstream TV show like The Sarah Connor Chronicles unfolds in a way that affirms a literal and inerrant reading of the Book of Revelation, it’s hard to ignore the influence of fundamentalism on American culture. Surely, it’s good that mainstream networks are showing signs of taking religion seriously, rather than using it as a backdrop for an explosive chase sequence. But is this really progress?

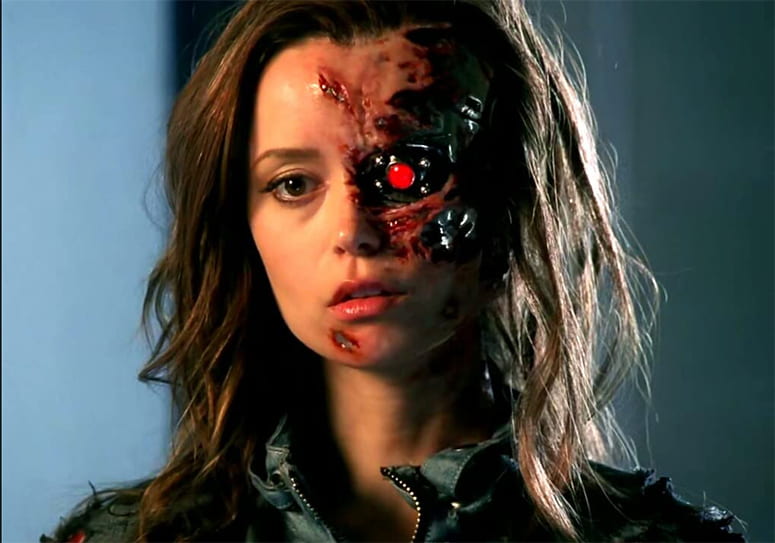

Terminator: The Sarah Connor Chronicles, Fox.

Every epic needs a hero, and the obvious messiah of The Sarah Connor Chronicles is John Connor (note his initials). It’s John who will one day lead the human resistance against the machines. As saviors go, he’s a bit of an odd duck. Throughout the first two seasons (not to mention the preceding films), a rotating bodyguard of soldiers is ferried back through time to pass information, fight, and kick the bucket. Instead of dying to save the world, it’s the world, it seems, that has to die for him.

The real Christ figure, it turns out, is Cameron, the “good” Terminator whose job it is to protect John. Played by Summer Glau, a lithe, willowy actress with a round, childlike face, Cameron has been designed to infiltrate social networks by imitating human behavior and emotion. In a great scene set in a Los Angeles ghetto, Cameron copies a teenage girl she sees leaning on the hood of a car. After careful study, Cameron downshifts her motorized frame into a more casual, gangland patois, even brushing a stray lock of hair from her face. She may be a cyborg, but Cameron’s strategy of blending in by mimicking the “cool girl” in the neighborhood isn’t noticeably different from what millions of teenagers do every day.

Cameron’s satire of the all-American teenager is so familiar that it’s easy to forget she’s not human, especially in the moments when she seems to be evolving beyond her programming. In the second-season premiere, Cameron reveals a certain curiosity about matters of the soul. After a particularly tough day, in which she’s blown up in a car, electrocuted by an alarm clock in a tub of holy water, and pinned between two delivery trucks, Cameron becomes preoccupied with a statue of a bleeding Jesus, and asks Sarah Connor if she believes in the Resurrection. There may well be a ghost in this machine.

There are other reasons that Cameron makes a compelling messiah. Since cyborgs feel no pain, she skirts the pesky, ancient theological debate over whether a God who is perfect and changeless can also suffer. She also sports a mysterious dual nature. Whether her nonhuman half is machine or divine doesn’t matter, since the God whose designs are revealed in The Sarah Connor Chronicles is rather mechanistic himself. Like the fundamentalist God of “Left Behind,” the divine mind behind The Terminator is a lot like the chariot in Ezekiel’s vision: a perfect machine rolling its way inexorably across the heavens, divine causality radiating from every spoke. Cameron is neither devil nor Antichrist but an avenging angel, executing a historical program set down in the primeval binary code of good and evil. Christian fundamentalists may be a lot more complicated than machines, but the God of “Left Behind” and The Terminator is not.

In the playground battles over Star Wars and Star Trek, I was always a partisan of Lucas. The simple reason was that Star Wars told better stories and offered a richer account of the human condition. To a child, the universe is fundamentally irrational, strange, and ruled by capricious authorities. Trek was fun, but its hopeful vision didn’t linger in the depths or grapple seriously with the problem of evil. The new, grown-up sci-fi is another matter. In Battlestar Galactica and The Sarah Connor Chronicles, history is not a tale of infinite progress but a tenuous struggle between mysterious forces we understand only in part.

Bible prophecy and science fiction share an obsession with the future. Or put another way, each taps the future to allegorize our present discontents. Whether channeling the romantic critique of industrialization and the Scientific Revolution, spreading secular utopianism in the postwar era, or providing catharsis from the anxieties of the cold war, the genre has always been better at describing what is than speculating on what might be, at holding a glass to our current fears and hopes. In the early twenty-first century, those fears often center on the resurgence of religion and its potential to inspire apocalyptic violence. If the original Star Wars were released today, it’s hard to imagine that it wouldn’t be greeted with more ambivalence. In 1977, it was easy to cheer for the naïve, disaffected youth from a remote, third-world planet who falls under the spell of a charismatic guru, converts to an ancient warrior faith, and uses his religious training—and his skills as a pilot—to humble a mighty empire, striking the heart of its military complex and toppling the steel colossus that symbolizes its strength. Twenty years later, that Hollywood ending carries a different resonance.

By offering gritty realism instead of camp, the new sci-fi has expanded its audience beyond a phalanx of hard-core, socially challenged fanboys and made a bid for social relevance. Perhaps that’s a mixed blessing. By confining itself to the darker strains in American culture—the collective post-traumatic stress disorder of 9/11 and the Iraq war—the new sci-fi may be in danger of falling prisoner to it. For generations of geeks, science fiction has promised the luxury of escapism, the ability to leave behind our disenchanted universe for one pregnant with potential. For all the thrills in Battlestar Galactica and The Sarah Connor Chronicles, there’s not a lot of simple joy to be had. It’s enough to make you pine for Captain Kirk and a few photon torpedoes.

Brett Grainger is the author of In the World but Not of It: One Family’s Militant Faith and the History of Fundamentalism in America (Walker and Company, 2008) and a doctoral student in American religious history at Harvard Divinity School.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.