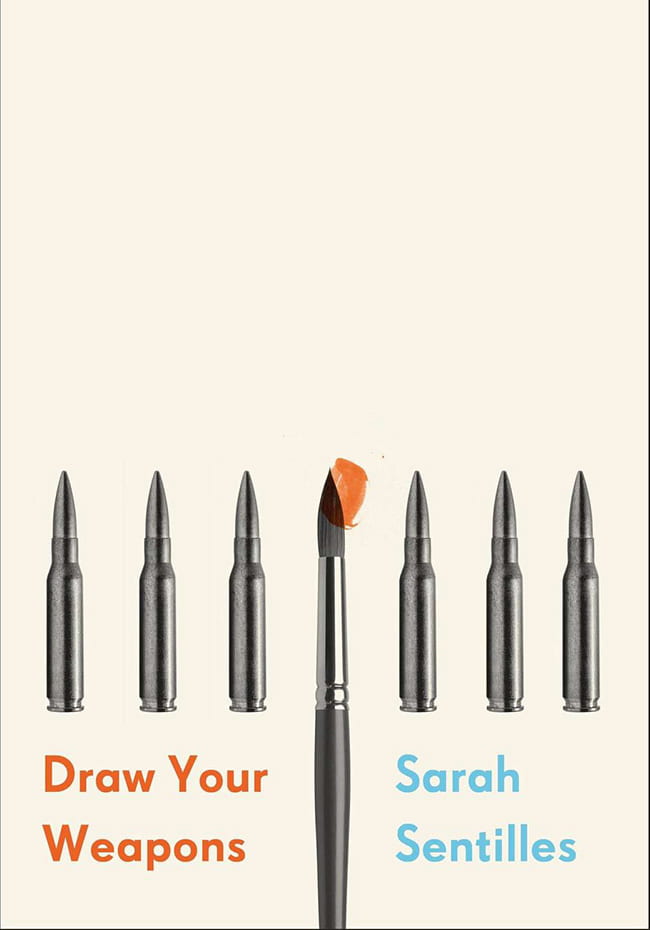

‘Peace, Peace to Him Who is Far Off, and to Him Who is Near’

Pacifism involves profound dilemmas and vast implications.

By Sarah Sentilles

As a child I wondered why political conflicts couldn’t be solved by playing a game instead of fighting wars. Why not chess? Football? Monopoly? Soccer? I grew up during the Cold War, and I’d imagine the Russians on one side and the Americans on the other, the players in their uniforms, the referee firing a gun in the air to start the match, the only shot fired.

I’ve called myself a pacifist for most of my life. I thought it let me off the hook somehow, as if being against the wars my country fights means they have nothing to do with me.

♦♦♦

I know it is futile to attempt to extricate myself from the evils in which we are involved, Howard Scott wrote in a letter to his wife, Ruane, from prison. A conscientious objector during World War II, Howard had worked in Civilian Public Service (CPS), fighting forest fires. Howard’s college roommate, Gordon Hirabayashi, and his family were ordered to internment camps, and when Gordon refused to go and was arrested and imprisoned, Howard decided being a conscientious objector was not protest enough. To resist war and conscription and internment, Howard walked out of the CPS work camp without permission. He, too, was arrested and imprisoned. I remain a part of the crimes committed by us. . . . And I do not wish to separate myself from society or my group. I need to intentionally make myself more a part of it.

♦♦♦

In high school, watching a documentary film about the Nuremberg trials, Howard’s daughter, Kayleen, vomited. Threw up again and again. She was sitting next to her friend Ruth.

Ruth’s grandparents had been made to run for their lives in a farm field in Germany, chased by a hay baler driven by Nazis, until the machine caught up with them and ran them over.

♦♦♦

Pacifism is a pathology of the privileged, Ward Churchill argued. It’s easy for those who are not oppressed to advocate nonviolence, easy for the powerful to use the ideology of pacifism as a tool with which to further oppress those who are unwilling to take up arms to defend human rights.1

The weaker parties in social conflict are forced by the stronger party to employ nonviolence, Herbert Marcuse insisted.2

♦♦♦

Most of Emmanuel Levinas’s family was killed in the Holocaust. A philosopher, Levinas wanted to create an ethical system that might make future genocide impossible. He started with the face of the other: The face as the extreme precariousness of the other. Peace as awakeness to the precariousness of the other.3

In class, to explain what he meant, I drew two stick figures on the whiteboard, facing each other—labeled one I, labeled one Other. For Levinas, when you encounter an other, you recognize your own vulnerability—the other could kill you—and you also recognize your power—you could kill the other. The impulse to kill must be resisted, he argued. I could kill you must be replaced with Thou shall not kill.

I drew lines from the head of the figure labeled Other on the whiteboard, as if the face were a sun, my lines its rays. From the face of the other shines that which makes one person unlike anyone else, I said—irreducible alterity, Levinas called it—an otherness that cannot be replaced, that cannot be understood or contained, that once lost can never be recovered. You are held hostage by that otherness, which you must protect at all costs, even at the cost of losing your own life, because, for Levinas, that otherness is God.

♦♦♦

Sarah Sentilles

Critics insist pacifism results from an internal contradiction: pacifists claim to be against using violence because they respect life, yet how can you claim that life is an absolute good and then be unwilling to defend lives threatened by aggression?4

But advocates of pacifism point out that pacifism is no more contradictory than the idea that you must kill life to defend life, that you have to destroy the village to save it.

♦♦♦

I still see those images from the films in my head, Kayleen told me. I still have nightmares.

After Kayleen saw the footage from the death camps, she asked her father, How could you not go to war?

I can’t kill because others are killing, Howard said.

But how could you not go to war?

All killing has to stop, he said. It is a sickness all over the earth.

♦♦♦

I projected a photograph of an Iraqi girl splattered with her parents’ blood onto the screen at the front of the classroom. The girl is young—five years old—and there is blood in her hair, on her hands, on her dress. Her mouth wide open, she screams.

She’d been riding in a car with her family to take her brother to the hospital when American soldiers at a checkpoint opened fire, killing her mother and father. I didn’t yet know the girl’s name (Samar Hasan), but I wanted my students to look at her. To look at her gray dress patterned with flowers as red as the blood on her body, on the concrete, on the toe of the boot of the soldier standing next to her, who is holding a gun and shining a light in the dark.

The students’ desks faced the screen onto which all semester I’d projected image after image of other people’s pain. Men lying facedown in the dirt next to a bus, hands cuffed behind them, shot in the head. A body floating in the water after Hurricane Katrina. A man falling headfirst out of the towers. A line of dead bodies, each partially covered by a white sheet. A skeletal child curled up on the ground, a vulture waiting. The girl in the flowered dress.

A student raised her hand. But what are we supposed to do? she asked.

Through the classroom window, blue sky, sunlight, palm trees, birds-of-paradise, succulents growing out of the university’s tiled rooftops. The sound of someone cutting the lawn in the quadrangle just out of sight. The smell of pepper trees, eucalyptus, ocean.

I don’t know, I said.

♦♦♦

A skeptical version of pacifism can develop from the worry that when we choose to kill in self-defense, we can never know whether this killing is in fact justifiable. At the level of personal violence, you can argue that an aggressor deserves the violence inflicted on them, but at the level of war, the personal element is lost. Masses of people are killed without any concern.5

♦♦♦

At Auschwitz, where the ashes of victims, scattered by the wind, are still part of the fields and rivers and ponds, there were six orchestras. There was music in those camps, prisoners forced to play while people marched to their death. They played for jam, for bread, for cigarettes. They played for their lives. The instruments’ f-holes, open to the sky, must have caught ashes falling like snow, becoming caskets, urns, tombs, the only burial given.

Years ago, Amnon Weinstein, an Israeli violin maker, was working in his shop when a man brought in an old instrument and told Weinstein it had been played at a death camp. When Weinstein separated the belly from the back, he found the wood inside black and lined with ash.

He and his son have restored more than sixty instruments from the camps. Each violin like that that you are going to play, Weinstein said in an interview, it’s for millions of people that are dead.6

♦♦♦

Transformational pacifism: a broad framework of cultural criticism that includes efforts to reform educational and cultural practices that tend to support violence and war. In the future, people will look back at war and violence as archaic remnants of a less civilized past.7

♦♦♦

I believe we can best witness for truth by transforming lives in the light of the truth we see, Howard wrote to Ruane. Of course, I must begin with myself.

Surely civilization will perish if we rely on war.

♦♦♦

My father went to prison for peace, Kayleen told me. He wanted to demonstrate with his life that taking up arms is the problem. If we continue to take up arms, how do we do anything but contribute to the Holocaust? For him it was a clear commandment: Thou shall not kill.

I still wrestle with my dad’s decision not to fight, Kayleen said. I am appalled by the annihilation perpetrated by the Nazis. It’s hard not to want to do the same thing to the people who do these things, she said. But I believe wholeheartedly that my dad’s stand was the right stand to take.

It would be my stand, she said, though I’m amazed at what it takes to make that stand heard, for it to have any impact at all.

♦♦♦

The religious discourse prior to all religious discourse is not dialogue, Levinas wrote. It is the “here I am,” said to the neighbor to whom I am given over, and in which I announce peace, that is, my responsibility for the other. . . . “Peace, peace to him who is far off, and to him who is near.”8

♦♦♦

I watched a video of Gordon Hirabayashi talking about his time in prison.9 His mother wrote him once a week, a half page of typed words, a summary of events at Tule Lake, where she was interned. In one letter she told this story: When she first arrived at Tule Lake and was unpacking, a knock came and she opened the door, and there stood two women, shoes dusty. They said, We heard that the family of the boy that’s in jail is arriving today, so we came out to welcome you and to say thank you for your son.

When Hirabayashi read these words in his mother’s letter, a weight left his shoulders that he hadn’t realized he was carrying. His mother had pleaded with him to go to Tule Lake with her. I admire what you’ve done, she’d said. I agree with you, but if we get separated now, we may never see each other again. If the government could do this sort of thing, they could keep us apart, so please come with us. Hirabayashi told her he couldn’t go with her.

I wouldn’t be the same person if I went now, he said. I took a stand and I can’t give it up. Even her tears couldn’t change his views, but he felt guilty. He had failed to respond as a dutiful son.

When he read the letter about the women visiting his mother, he said, I knew standing there next to her wouldn’t have given her the same kind of lift.

♦♦♦

Here I am, says every prophet called by God in the Bible, a phrase that is an English translation of the Hebrew word hineni, which means ready, a word the prophets speak before they know what they’re being asked to do.

♦♦♦

Will they send you a letter if you have to go back? I asked my student Miles when he told me he’d reenlisted in the army reserve. He’d been a soldier at Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq, and now he was home.

They’ll just call me, he said and held up his phone.

Can you say no?

♦♦♦

Kill or be killed—some pacifists argue this is a false dilemma, insist there are nonviolent alternatives. Resorting to violence is a failure of imagination, they say. You abandon hope for more humane ways to solve conflict.10

♦♦♦

Our weapon is the smallest possible, Ruane wrote to Howard.11 Nobody can find it. Even with all their brainpower and ingenuity the task would be impossible. The effect of the weapon is visible and traceable, but the weapon itself is never found. In an age of swords, its effect is peace, joy, frankness, and faithfulness to what is holy. No other weapon can compare with it. It melts ice, spreads lift, brings warmth. It creates and alters, drives out doubt and despondency, and stands guard. It marches victoriously through locked gates, so that he who sits in prison finds consolation.

♦♦♦

In a greenhouse, scientists divided plants into two groups, lined them up along walls of glass and light. Assigned to the first group were volunteers whose job was to look at the plants with love for hours at a time; assigned to the second group were people told to watch the plants with indifference.

After a few weeks, researchers discovered the volunteers’ gazes had affected the structure of the plants’ cells. The plants looked at with love had strong cell walls, while the cell walls of the plants looked at with indifference had collapsed.

♦♦♦

I watched my father drown, Howard said. On the shore. Jumping up and down and waving.

We all have secrets inside, shame covering them like dirt.

When Ruane died, her body gave off so much heat we sang songs about snow, Howard said.

There’s more than one way to fight.

Notes:

- Andrew Fiala, “Pacifism,” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, July 6, 2006, revised August 14, 2014, plato.stanford.edu/entries/pacifism.

- Ibid.

- Judith Butler, Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence (Verso, 2004), 128–51. For the line that begins the face as the extreme precariousness of the other, Butler is quoting Levinas’s essay “Peace and Proximity.”

- Fiala, “Pacifism.”

- Ibid.

- “Restoring Hope by Repairing Violins of the Holocaust,” PBS NewsHour, February 12, 2016.

- Fiala, “Pacifism.”

- Emmanuel Levinas, Of God Who Comes to Mind, trans. Bettina Bergo (Stanford University Press, 1998), 75.

- See on Youtube, “Densho Oral History: Gordon Hirabayashi” and “Receiving Encouragement from Mother: Gordon Hirabayashi.”

- Fiala, “Pacifism.”

- Ruane is possibly quoting someone here (a letter? a book?), but in her own letter, she does not indicate what or who she is quoting, and I have not been able to locate the source.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.