In Review

Lessons in Dignity and Divinity

We can glean much wisdom from The Life of Omar Ibn Said.

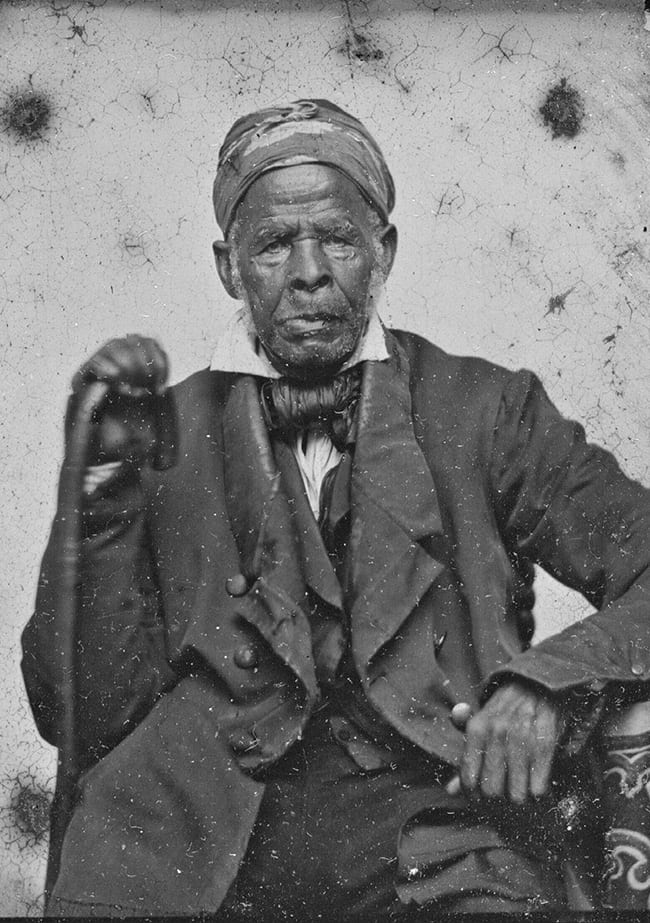

Omar ibn Said, ambrotype daguerreotype, by unknown photographer. Randolph Linsly Simpson African-American Collection, Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Yale University

By Melissa Bartholomew

I reside in our country here because of the great harm. The infidels took me unjustly and sold me into the hands of the Christian man (Nasrani) who bought me. We sailed on the big sea for a month and a half to a place called Charleston in the Christian language. I fell into the hands of a small, weak, and wicked man who did not fear Allah at all, nor did he read nor pray. I was afraid to stay with such a wicked man who committed many evil deeds so I escaped. After a month, Allah our Lord presented us into the hands of a righteous man who fears Allah, and who loves to do good deeds and whose name is General Jim Owen and whose brother is called Colonel John Owen. (Omar ibn Said, The Life, 77)

Our country has never been a place without conflict. The size or scale of the struggle has varied across time, but its existence has always been apparent if one has eyes that see. One of the persistent challenges of a nation that emerged out of overwhelming human suffering (the genocide of Native Americans and the enslavement of Africans) is that it still struggles with unresolved, complex human dilemmas. Painful periods along the trajectory of our nation have caused some to struggle not to lose their faith in humanity. Opposing views and polarizing positions can lead, and have led, many to develop feelings of disconnection from an individual, a people, or a political party whose views and positions they find troubling and even frightening. Yet I believe such moments of fear and disconnection give value to religion and its ability to create a framework that can reorient us to a place of reconnection with each other.

We would do well to look back in history at examples of people in our country who have used religion as a strategy to enable them to hold on to their humanity and to their belief in the humanity of others, even their oppressors, while living under inhumane conditions. One group we can draw wisdom from is enslaved Africans, brought to this country or born here, who used their own brand of religion to help maintain their dignity and divinity. Theologian Howard Thurman absorbed these lessons from his grandmother, a former enslaved person, who received the teachings from a “slave minister” who would hold secret religious gatherings with other enslaved people. His grandmother repeatedly relayed the minister’s message that they were not slaves; they were children of God. According to Thurman, “This established for them the ground of personal dignity. . . .”1 Like Thurman’s grandmother, many enslaved people harnessed their spiritual power to transcend oppression and to negotiate their way through life enslaved. Another enslaved person whose life illustrates these qualities is Omar ibn Said.

Omar ibn Said was an African Muslim who was captured as an adult from West Africa and sold into slavery in the United States around 1807.2 His autobiography, written in Arabic, reveals his commitment to Islam and to Christianity.3 On the same page that contains a prayer request for his heart to be open to the path of Jesus Christ—he notes that his slave masters read from the Bible—he also asserts that his religion is the religion of Muhammad, the prophet of Allah:

Jim with his brother read from the Bible (Ingeel) that Allah is our Lord, our Creator, and our Owner and the restorer of our condition, health and wealth by grace and not duty. [According?] to my ability, open my heart to the right path, to the path of Jesus Christ, to a great light.

Before I came to the Christian country, my religion was/is the religion of Mohammad, the prophet of Allah, may Allah bless him and grant him peace. I used to walk to the mosque (masjid) before dawn, and to wash my face, head, hands, feet. I [also] used to hold the noon prayers, the afternoon prayers, the sunset prayers, the night prayers.

I used to give alms (zakat) every year in gold, silver, harvest, cattle, sheep, goats, rice, wheat and barley—all I used to give in alms. (67, 69)

A couple of pages later, Said asserts his love for the Qur’an before he mentions the Bible. He uses the same language such that this passage serves to bookend the earlier one:

I am Omar, I love to read the book, the Great Qur’an.

General Jim Owen and his wife used to read the Bible, they used to read the Bible to me a lot. Allah is our Lord, our Creator, and our Owner and the restorer of our condition, health and wealth by grace and not duty. [According?] to my ability, open my heart to the Bible, to the path of righteousness. Praise be to Allah, the Lord of Worlds, many thanks for he grants bounty in abundance. (73)

A Muslim American Slave: The Life of Omar Ibn Said

Said converted to Christianity from Islam while enslaved, but his autobiography reveals that he retained elements of his Muslim faith. For example, he presents the Islamic prayer, the al-Fatiha, together with the Christian prayer, the Lord’s Prayer. Kambiz GhaneaBassiri, one of several scholars who has interpreted Said’s autobiography, explains that “By presenting them as interchangeable practices of Islam and Christianity, ‘Umar did not syncretize these two religions; rather, he established a poly-religious common ground that maintained the distinctness of each religion while at the same time allowing him to step in and out of both.” According to GhaneaBassiri, Said’s autobiography reveals that Said viewed the Qur’an and the Gospels as “functional equivalents” from the same divine source and that Said moved in and out of the Muslim and Christian worlds by maintaining a shared concept of God as Lord of all. He contends that while Said was aware of the differences between the two religions, his embrace of their commonality provided the space he needed to be able to enter into a “communal relation of sorts” with his slave masters.4 This is an example of the extraordinary things that happen when people commit to a shared concept of God.

GhaneaBassiri describes one of the compelling features of Said’s autobiography and what he believes it reveals about the power of Said’s religion:

The first four pages of ‘Umar’s thirteen-page autobiography is a more-or-less accurate transcription of the 67th chapter of the Qur’an, al-Mulk. Mulk means “possession” or “property” in Arabic, and when applied to God’s relation with the world, it also refers to divine providence. Theologically, this chapter of the Qur’an underscores God’s sovereignty over every aspect of life and warns those who ignore divine guidance or who assume that God is not aware of their every thought and action and that God is the All-knowing and vigilant judge of humanity. . . . Neither theology nor magic could alone explain why a slave would begin his autobiography by citing God’s own words on divine providence. Here again we see how the polyvalence of Islam helped Muslims form relations with others, including those who legally possessed their body and labor. On the one hand, ‘Umar denied his human master’s power over him by acknowledging God’s power over all things. By placing his life in God’s hands he also avails himself of divine protection. Divine providence also softens the inhumanity of slavery, which allows us to fathom why ‘Umar would have regarded the Owens, whose chattel he was, as “righteous men.” While Christian slavers evoked divine providence to justify slavery, ‘Umar invoked God’s mulk to endure slavery. The slave and the slaver met on the plain of providence and held each other accountable before God.5

Here, GhaneaBassiri illuminates how Said demonstrated the transformative power of religion, a power that is evident when a beholder utilizes his or her religious faith to connect to God and allows God’s power to move through him or her and shape his or her way of being in the world. Islam was a shelter for Said and protected him from the inhumanity of enslavement. He allowed the concept of mulk (possession or property) to help him cope with his harsh reality as another man’s property, but never to justify it. Consider this poetic line from his transcription of al-Mulk:

Do they not see the birds above their heads, spreading their wings and closing them? None save the Merciful sustains them. He observes all things. (55)

As the birds are sustained and observed by a merciful God, so are the humans on the ground. Said’s testimony reveals that although enslavement was his physical position, it was subject to his spiritual condition as one possessed and controlled by God. God’s power superseded the power of his slave master and was his shield of protection. It also stabilized him and reminded him of the humanity of those who enslaved him. It is the commonality of belief in the power of God that allows Said to call Jim Owen “a righteous man who fears Allah” (but note that he uses the words and framework of his own faith here, not those of his enslaver’s religion). Said’s understanding of mulk as God’s providential presence gave him the ability to see beyond his enslaver’s acts of oppression and to meet him “on the plain of providence” in the presence of God.

This is the miracle of Islam—and of any religion—which serves as a vehicle for one to see God, and humanity, in one’s oppressor. In Said’s life, Islam and Christianity worked together to enhance his spiritual capacity, allowing him to maintain his relationship and commitment to God and to refrain from being consumed by hate and revenge. His spiritual power enabled him to recognize his slave master as his equal before God.

Said’s life sustained through religion is just one example of the way religion can serve as a spiritual resource for us, enabling us to see the humanity in those we disagree with or who even oppress us. His ability to meet his enslaver on the plain of providence in the presence of God is a reminder to us that we have the capacity to do the same, and that we do not have to rely on our human efforts alone. Through connecting with God’s divine providence and protection, we can meet our opponents, even our oppressors, where they are and never lose sight of their humanity. I believe that this is the strategy that those of us who are people of faith must employ to resolve our enduring conflicts and move our nation forward.

Notes:

- Howard Thurman, Jesus and the Disinherited (Beacon Press, 1949), 50.

- Kambiz GhaneaBassiri, A History of Islam in America (Cambridge University Press, 2010), 18. In the text, Said describes his birthplace as “Fut Tur, between the two rivers [or seas],” which scholar Michael A. Gomez has noted is the “middle Senegal valley” area, which lies between the Senegal and the Gambia Rivers in western Africa. Michael A. Gomez’s essay, “Muslims in Early America,” Journal of Southern History 60, no. 4 (November 1994), is reproduced in A Muslim American Slave.

- Omar ibn Said’s life story, composed in 1831, is the only known surviving American slave narrative written in Arabic.

- GhaneaBassiri, History of Islam in America, 85–87.

- Ibid., 89–90.

Melissa Wood Bartholomew, MDiv ’15, is a Christian minister, lawyer, and mediator. She is a PhD student at Boston College School of Social Work. Her research explores the impact of racism and historical racial trauma on the descendants of Africans enslaved in America and the role of faith and forgiveness in their healing and resilience. She recently had a chapter published in Trouble the Water: A Christian Resource for the Work of Racial Justice (Nurturing Faith, Inc., 2017).

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.