In Review

Patterns from Particularities

By Steven P. Hopkins

Differences and similarities are critical in comparative studies, and the cross-cultural study of religion is suited to be a powerful witness to both. I would argue that a focus on strong cross-cultural comparative themes is the most effective approach in the study of religion and religions. The key is finding themes that are, in the phrase of Claude Lévi-Strauss, “good to think with,” that do not shut out good conversation, but, like Paul Ricoeur’s symbols, “give rise to thought.” The best use of comparative themes—love, death, evil, pilgrimage, the body, thanksgiving and gratitude, humanity and the human—does not naïvely presuppose universal experiences or univocal typologies across cultures or religions, but generates sometimes surprising new questions, incongruities, juxtapositions that, on occasion, inspire fresh insights and, sometimes, strange and unexpected congruities.1

My growing conviction is that only through what might be termed a colloquy of particularities will relevant general patterns potentially—and only potentially—emerge in the comparative study of religions. I believe the thematic approach is the most effective way of affirming both religious and human particularity and implicit potential common patterns of religiousness in the realms of religious thought and actions.2 That said, we should not attempt to anticipate the outcome of any comparison, in that particularity may very well be, in some of our most important encounters, irreducible, the tensions and antinomies irreconcilable.

I attempt to address such issues in my teaching by dealing not only with theologies, religious ideas, or heuristic typologies, but also with practice, a focus on the facts of daily human religiousness. Within the context of the Indian subcontinent, I emphasize not only normative doctrines that set Hindus, Buddhists, Jains, Christians, and Muslims apart from one another as bounded, reified entities, but some common patterns of worship and piety that unite them, that blur the boundaries, often in ways that threaten orthodoxies. We spend as much time, for instance, on relic and tomb veneration among Christians, Muslims, and Buddhists as we do on their doctrines of the trinity, divine unity, and impermanence.

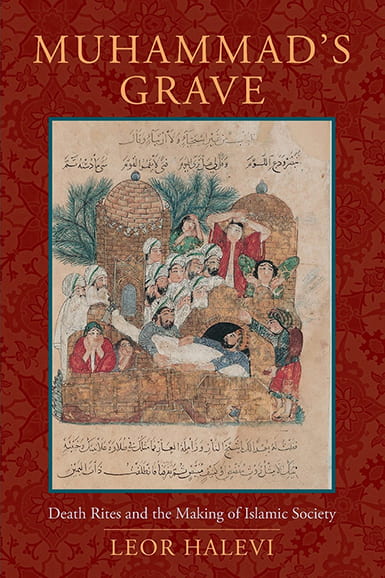

There are two good models of scholarship in recent years that might help us engage in new ways of thinking, either historically or in the study of contemporary religiousness, about the study of world religions outside of the inherited nomenclature: Jean DeBernardi’s The Way That Lives in the Heart and Leor Halevi’s Muhammad’s Grave.

The Way That Lives in the Heart

DeBernardi’s The Way That Lives in the Heart is a rich study of the habitus of Chinese popular religion, with a focus on spirit mediums and vernacular religious narratives on luck, fate, (fragile) power, prosperity, and wealth in contemporary Penang, Malaysia. Among its many virtues, this book contains one of the clearest discussions to date of the development of streams of practices we call “spirit medium (popular) religion” and “shamanism” through Southern China down into Southeast Asia. This focus on living Chinese spirit medium cults, which are at the nexus of popular religious practice in contemporary Penang, reveals a complex social and linguistic landscape that challenges any singular notion of “religion” or even “Chinese religion.” One is confronted here by a variety of linguistic forms and compound particularized identities: Nonya Chinese; Hokkien Chinese immigrant; anglicized Straits Chinese, Mandarin-educated Chaozhou.

DeBernardi’s field studies include some important spirit mediums, from Datuk Aunt, a woman spirit medium possessed by Malay animist spirits (Datuk Gong) who offers her clients remedies for “spiritual collisions,” and Master Poh, who mixes and mingles classificatory and ethical terms from Buddhism, Daoism, and Confucianism, to the more theosophically orthodox Master Lim, who claims a modern Theravada Buddhist monk as central influence. These studies serve to complicate many easy boundaries between Daoist, Buddhist, and Confucian “religions,” and even a singular reified notion of “spirit medium religion” itself. The sober Gautama Buddha of normative Pali narratives is present in Master Lim’s vision of the ideal Daoist ethical life, but there is also Master Ooi’s antinomian brandy-swilling and Guinness-chugging Vagabond Buddha who dispenses black charms for healing, prosperity, and “invulnerability magic” in religious “antilanguage.”

The common theme that surfaces in this colloquy of particular forms of religious practice is hardly reducible to simple doctrinal formulations, though we might speak loosely of a vision of the fragility of the good life, with misfortune as its twin, and its reliance on a slippery and sometimes seemingly random sense of luck mediated by rituals. DeBernardi’s study of the spirit medium habitus forces a reassessment of Max Weber’s critiques of spirit religion and the “magic gardens” of the heterodox cults, for we have here a perfect-pitch point for capitalist entrepreneurship in the “magical” worlds of spirit cults, where the elaborate rituals for ancestors/ghosts/spirits/deities address the satisfaction of material needs, spiritual welfare, “mending luck,” karma, and economic status, in contrast to the “rational” ascetic economies of Confucian ideology.

A thematic, comparative focus on premodern and contemporary spirit cults, ancestor worship, the care of death and the dead, spirit possession, and ghosts is a potentially fruitful one for many areas of study. In my own area, forms of indigenous South Indian and Indian Pentecostal communities would be part of such a colloquy. Finally, another critical theme that emerges from DeBernardi’s study, though she does not fully develop it, is the unique religious formations of “island cultures.” The particularly hybrid and cosmopolitan religious formations of “island cultures” and lands with global littoral zones is one of those “good to think with” themes that could be expanded into a working theme for a symposium.

Muhammad’s Grave

Leor Halevi’s Muhammad’s Grave focuses on some of the most moving, powerful, existentially critical, human ritual actions associated with the dying and the dead in early Islamic communities. These practices range from corpse washing, shroud weaving, tombstone construction and inscriptions, and grave building to women’s mourning rituals, the plight of impoverished widows, and the eschatological destinies of the dead in al-barzakh (after life but before resurrection, the “betwixt-and-between” of the grave)—their angelic tests, blissful visions, or tortures (adhab).

Halevi’s work is a model of careful historical analysis, as he traces various sociocultural transformations of Islamic ritual practices concerning the dead from their Medinan and Meccan origins, to the spread of Islamic religious communities into South Arabia, Mesopotamia, and the Mediterranean world. In a vivid, close reading of Qur’anic and commentarial sources, he charts the growing gaps between “traditionalist discourse” (the imaginary of our reifying lawmakers) and the practices of individual Muslim communities as the religion spreads across territories and in the neighborhoods of various other religious communities (Christian, Zoroastrian, and Jewish).

The choice of such “quotidian” matters as burial practices gives us a compelling comparative lens through which to study examples of religious continuities and change through time and space, and through various political and social milieux. Such a comparative theme also shows that law and daily practice, theology and the ritual lives of persons, are not mutually exclusive monads, but affect each other. In Halevi’s words, “Islamic law at its origins was not exclusively reactive but also in part adaptive.” The paradox of Islamization is that many of the processes frowned upon by the early ulema were in great measure responsible for the rapid and effective growth of the religion as it spread from its roots in eighth-century Medina. And we see this “paradox of Islamization” most vividly portrayed in various forms of death rites.

Halevi’s work brings into focus other fruitful themes that could invite a variety of responses from local/vernacular and translocal forms of world religious traditions beyond reified boundaries: “daily life,” the quotidian imaginary, death rites, and the hallowed dead; saint’s shrines as dynamic transactional spaces, as loci of multireligious participation; and laments, most particularly, the roles played by women’s laments and the manifold ways women’s ritual laments are appropriated by men in public commemorative rituals.

Though these two books resist reified religious boundaries, it can be argued that we actually do live now, for good or bad, in an era of reified religions, of religion as an exclusivist category; that there are indeed people all over the world who identify themselves normatively, rationally, creedally, and generically, in the most imperialist “world religions” fashion, as Buddhist or Hindu or Christian. These adherents affirm passionately, often through the online voices not only of traditional scholars but also of “gifted” and not-so-gifted “amateurs,” a bounded rational and doctrinal reality that they would unflinchingly call Buddhism, Christianity, or Hinduism, with a decided emphasis on the “ism.” We have strayed far from—if we were ever very near—the potential unitary global transformations imagined by Wilfred Cantwell Smith in Towards a World Theology. To reverse Smith’s formulation, for a great many religious persons, religious particularity precedes solidarity, and their religious orientation is not only a form, but also, and perhaps mainly, an object of consciousness.3 These forms of religiousness need to be a focus of our current study.

It is also true that in some circles one’s identity as generically Native American or American Indian, whether one is from the Navaho, Lakota-Sioux, Chippewa, or Len-ape nation, is politically necessary and critical in gaining a stake in the game of “world religions.” This kind of reification is central in the very different context of powerful contemporary missionary projects being undertaken by evangelical and Pentecostal Christians in many parts of the world. These also need close study and attentive scholarly scrutiny as important contemporary examples of “global (world) Christianities.”

The reification of religion and religious identity is not only related to forms of al-Qaeda or Taliban Islam in Afghanistan or on the Pakistani borders, or traced in official pronouncements regarding normative forms of Catholic faith and “other religions” (most notably Islam, its “proximate other”) by Pope Benedict XVI in Rome, or found in Christian Pentecostal movements in Asia and the Americas. It is also evident in very distinct ways among middle-class and affluent Buddhists in New York and Boston, working- class Catholics in suburban Philadelphia, or Hindus in urban Chennai, London, or on the island of Kaua’i.4

What’s more, we see vivid examples of new forms of reified creedal religion in online blogs and other forms of cyberspace. One can create anything now on the web, the illusion of a singular bounded eternally normative community, or the elastic transparent structures of multireligion.5 These forms must be given voice in comparative religion scholarship, while scholars like DeBernardi and Halevi seek at the same time to lend their ears to local/vernacular, translocal, and transnational practices that break down the strict normative political boundaries between the “religions.”

In different but compatible ways, DeBernardi’s and Halevi’s books underscore that a comparative focus on forms of religiousness “on the ground” expands the conversation about the sometimes uneasy coexistence of “world religions” and the prodigious religious hybridity of our contemporary world.

Notes:

- In my reference to surprise and the discovery of incongruity in comparative studies, I am indebted here to the work of Jonathan Z. Smith. See his Relating Religion: Essays in the Study of Religion (University of Chicago Press, 2004), 179–196, 230–250, 251–302.

- I use the word “colloquy” here following Wilfred Cantwell Smith; see his Towards a World Theology: Faith in the Comparative History of Religion. (Westminster Press, 1981), 193.

- Smith, Towards a World Theology, 79, 93.

- There is a newly completed Iraivan Temple on Kaua’i founded by Satguru Sivaya Subramuniyaswami, part of the Saiva Siddhanta Church that has refashioned an ancient Hawai’ian sacred landscape in the shadow of the sacred mountain Wai’ale’ale in its own outh Indian Hindu image. See details on www.himalayanacademy.com.

- It can be argued, for instance, after a reading of Brian Axel’s work, that Khalistan, the separate Sikh state, already exists, and has existed now for some time (virtually), on Sikh nationalist websites; Brian Keith Axel, The Nation’s Tortured Body: Violence, Representation, and the Formation of a Sikh “Diaspora” (Duke University Press, 2001).

Steven P. Hopkins, PhD ’95, is Professor of Religion at Swarthmore College. He is the author of Singing the Body of God: The Hymns of Vedantadesika in Their South Indian Tradition (2002) and An Ornament for Jewels: Love Poems for the Lord of Gods (2007) and is currently completing a study of Sanskrit “messenger” poetry. These words are adapted from remarks given as part of the Center for the Study of World Religions’ 50th anniversary symposium held at HDS on April 15–16, 2010.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.