In Review

Paths to Abstraction: Spirituality in the Work of Three Women Artists

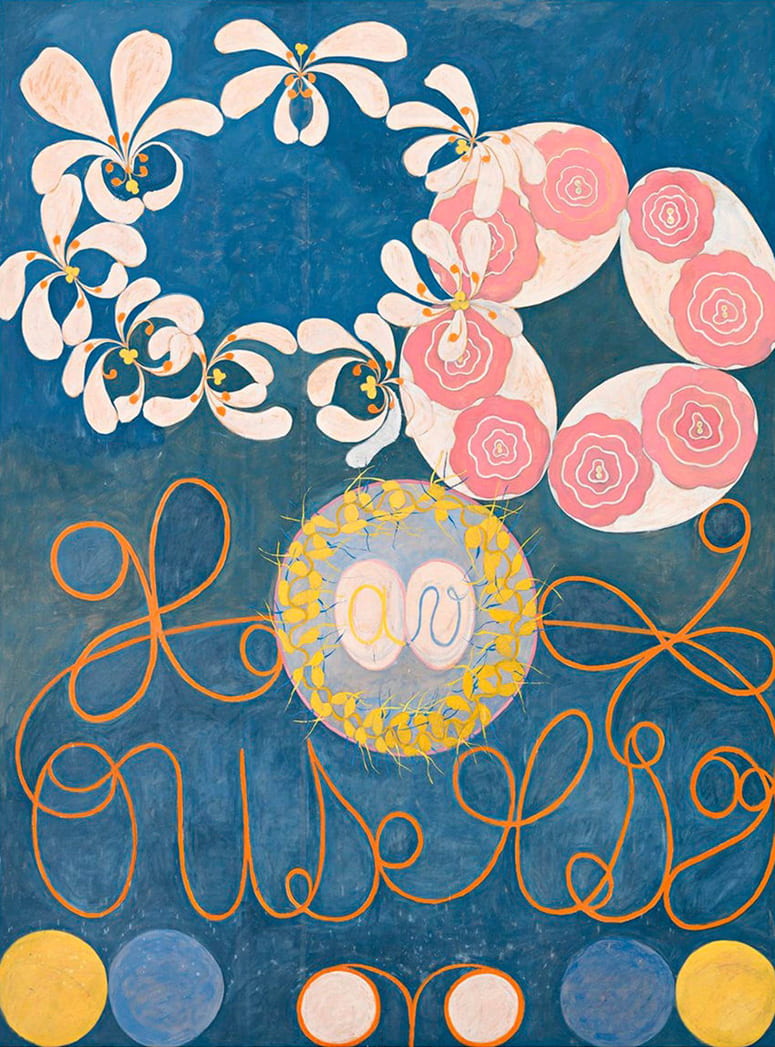

Hilma af Klint, Group IV, No. 3, The Ten Largest, Youth, tempera on paper mounted on canvas, 10’ 6” x 7’ 10 1/2” (1907). Courtesy the Hilma af Klint Foundation. Photo: Moderna Musset, Stockholm.

By Ann Braude

Art which is not religious is not art, it is mere merchandise.

—Isadora Duncan, “The Dancer of the Future” (1907)

“ ‘Hilma who?’ no more,” crowed New York Times art critic Roberta Smith’s review of Hilma af Klint: Paintings for the Future at the Guggenheim Museum (October 2018–April 2019). The most popular exhibit in the museum’s 60-year history introduced Americans to a pioneer of abstraction whose works have surfaced after sleeping unseen for nearly 100 years. The show attracted 600,000 viewers, increased museum membership by 34 percent, and broke sales records for catalogs and merchandise. New Yorkers’ enthusiasm for af Klint mirrored the response in her native Sweden, where Stockholm’s Moderna Museet mounted a pathbreaking af Klint exhibition in 2013.1

Why has the public now embraced af Klint’s enigmatic oeuvre? That a woman predates Vasily Kandinsky’s claim to have painted the first abstract painting is an obvious provocation, as is the fact that in 1907, the year Picasso painted Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, af Klint, in a mere six weeks, painted ten works that not only outsized Picasso’s disruptive masterpiece but also departed more radically from the conventions of European art.2 Af Klint was a disruptive visionary of a different stripe. Chronology, size, productivity, and even abstraction itself only hint at the shock of her work. Her paintings confront the viewer with an encompassing vision: artistic, spiritual, and emphatically modern.

While Picasso trained a male gaze on five naked prostitutes in a Barcelona brothel, af Klint fasted and prayed for guidance to paint images that would lead to a harmony beyond sexual difference. Many twenty-first-century viewers, it seems, find her path to abstraction as relevant as Picasso’s. Fascinated by the possibilities of nonbinary and transgender identities, admirers of af Klint embrace a painter for whom gender binaries were puzzles to be solved, not permanent features of reality. Instead of portraying the move from figurative to abstract art as a development linking modernity to an individualist secularism, af Klint’s abstract paintings suggest a modernity that proceeds from the past through a process of spiritual evolution.

Af Klint’s spiritual inspiration is being taken seriously, occupying center stage in lavish, internationally acclaimed twenty-first-century exhibitions. Respected curators argue both that af Klint’s work changes narratives of modern art and that it must be understood in relation to her religiosity. The af Klint family has encouraged curators to engage the artist’s intentions. Her work opens a door to an account of the birth of abstraction that embraces inventive spiritual experience as one path toward the transcendence of gender.3

As a move in that direction, I bring af Klint’s story together with those of two other women artists, Hilla Rebay and Vicci Sperry. Like af Klint, Rebay and Sperry each abandoned the limits of the physical form to paint a reality beyond objectivity. All three explored abstraction while they explored a new faith. And all three, for different reasons and to different degrees, have been absent from narratives of modern art.

Hilma af Klint (1862–1944)

Upon her graduation, with honors, the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Stockholm recognized af Klint’s mastery of portraits, landscapes, and botanical painting by giving her a studio in the academy’s buildings. While she refined the keen powers of empirical observation required for realistic painting, she applied the same goals to the investigation of Spiritualism, seeking observable evidence of spirit presence in séance circles. Eager for scientific proof of the immortality of the soul, she sat with other investigators, hoping that communication with the spirits of the dead would provide such proof. Af Klint joined the European Federation of the Theosophical Society when it was established in Sweden in 1889. There, with like-minded contemporaries, she explored the philosophies of Hinduism and Buddhism and searched for universal principles underlying all religions. While Spiritualists sought communication with deceased family members or other spirits who chose to demonstrate their presence in the séance room, Theosophists sought esoteric wisdom from great spirits from India and Tibet. Both Spiritualists and Theosophists hoped their search for hidden truth would complement scientific discoveries of invisible components of matter: the cell, the atom, the X-ray, and radioactivity.

Only after af Klint reframed her painting as spiritual exploration did she abandon European artistic conventions. The reframe took place in a séance circle formed with four other women, including Anna Cassel, a classmate from the Swedish Academy who would become a lifelong friend and co-investigator.

“The Five,” as they called themselves, took control of their own search for truth. They met weekly from 1896 to 1907, meticulously recording verbal and visual spirit messages for future study. They fashioned their own altar, directed their own liturgy, and formulated their own practices, combining multiple new and old approaches. They combined elements of both Protestant and esoteric Christianity, Spiritualism, Theosophy, and Rosicrucianism. They gathered every Friday for 11 years, kneeling in prayer and reading from the Bible, as they had since childhood in the Lutheran Church of Sweden. They also departed from familiar practices, preaching to each other, interpreting the Bible without recourse to religious authorities. Then, following spiritualist practice, they sat in a séance to become mediums for spirit communication. In keeping with Theosophy, they sought communication, not with deceased family members (as Hilma had done as a teenager) but with great spirits, “the High Ones,” fonts of Eastern wisdom. They gathered at an altar incorporating the “Rose Cross” of the esoteric Christian Rosicrucian Order. In this, they followed the lead of Rudolf Steiner, the well-respected Austrian philosopher whose studies of Goethe led him to become the leader of esotericism in Central Europe. As head of the German section of the Theosophical Society, Steiner steered Theosophists toward the esoteric traditions of their own region, in addition to those of Asia. He would later become a mentor to af Klint.

Séance circles occurred in many religiously liberal nineteenth-century homes. The Five were exceptional because of their exclusively female composition, the length and consistency of their explorations, the care with which they documented spirit communication, and their prior artistic training. In 1904, spirits foretold that af Klint would be charged to convey the spiritual world in paintings and that she would design a temple for display of the paintings she would complete. All five women were asked to undertake the spiritual paintings. Only af Klint agreed. On January 1, 1906, a spirit named Amaliel offered af Klint the “great commission” that would shape the rest of her life. She accepted without hesitation. At the age of 43, she committed to spending a year purifying herself and preparing spiritually to fulfill the commission. She would abstain from realistic painting and drawing, her livelihood for more than 20 years. According to Steiner, developing the spiritual senses was like being a blind person gaining sight for the first time. “The formerly dark world is suddenly radiant with light and color,” revealing “occurrences and beings that remain totally unknown to anyone who has not undergone a soul and spiritual awakening.”4 Ascetic practices would prepare af Klint to paint the unseen world.

When she completed the period of preparation and picked up her brush again, af Klint painted as a medium. That is, she did not control the brush but allowed her hand to be led by spirit control, with no image in her mind of what she would execute. The paintings that resulted bore no similarity to her previous work. These “exercises in automatism,” observed Guggenheim curator Tracey Bashkoff, may have helped af Klint unlearn her academic training as an artist, opening the door to experimentation.5 While af Klint retained, and sometimes used, her skills as a realist artist throughout her life, she added an additional visual vocabulary that incorporated multiple systems of communication: coloration, pictorial and alphabetic symbols, stylized writing and words, diagrams and geometric forms.

Hilma af Klint, Group IV, The Ten Largest, No. 1, Childhood, tempera on paper mounted on canvas, 10’ 7” x 7’10” (1907). Courtesy the Hilma af Klint Foundation.

For three years, with spirit guidance, af Klint painted with extraordinary discipline, completing 127 paintings in six thematic series, of what would ultimately become the 193 Paintings for the Temple. Most dramatically, The Ten Largest, nearly ten feet high, were completed over a six-week period. The five-foot-tall artist laid the paintings on the floor, as Jackson Pollock would famously do decades later, sometimes stepping on them to reach the destination of her brush. The Ten Largest depict the stages of life: childhood, youth, adulthood, and old age. Because of their size and number, she could not view the series in its entirety. The spirit moved her hand to create the image but did not reveal to her the full meaning of the works she created. Only after each painting was complete could af Klint contemplate its meaning.

She knew that the spirits intended the paintings to communicate spiritual knowledge, not just to her but to humankind. She knew that they depicted the unseen reality that Theosophists and other investigators saw as the basis for all religions, proven by science, “the dual nature of every object on Earth—in the spiritual and the material, the visible and the invisible nature.”6

What exactly they communicated she did not know. Some of the symbols were described, among other places, in Helena Blavatsky’s Secret Doctrine. A Russian occultist and student of world religions, Blavatsky co-founded the Theosophical Society in New York in 1875. Af Klint owned the Swedish translation of Blavatsky’s book. There, for example, the egg, a frequent symbol in The Ten Largest, received an entire chapter. According to The Secret Doctrine, the egg was “a universal symbol . . . incorporated as a sacred sign in the cosmogony of every people on the Earth.” In Sanskrit scripture, Blavatsky wrote, the egg represented the “ever-existing undifferentiated matter” that precedes creation. It symbolized the primordial unity out of which forms emerged when spirit separated from matter to give shape to the material world. Or it could represent the “auric egg,” the envelope which surrounds the individual, carrying their karmic inheritance from one life to the next through the process of reincarnation. Another recurrent symbol, the lotus blossom, was also universal. It represented “the abstract and the Concrete Universes . . . the productive powers of both spiritual and physical nature.” The lotus was dual-sexed, Blavatsky explained, containing all the elements of what the plant would become, fully formed in its seed before germination. She described it as “the two-fold type of the divine and human hermaphrodite.”7

Af Klint’s paintings swim with sexual duality, both mystical and biomorphic. Trained in botanical and anatomical drawing as well as mediumship, she was well equipped for the task. Yellow represented male and blue represented female, in sympathy with Goethe’s theory of color. Paired circles of blue and yellow overlapped in Venn diagrams to make green. Shapes resembling ovaries and testicles, as well as eggs and sperm, floated through the paintings, unattached to particular bodies or even species.8 A circle with a diameter line, which Blavatsky described as a double womb, connected to the mystical meaning of reproductive organs in diverse ancient cultures.

In the first of The Ten Largest, for example, a blue background suggested the sea of maternal gestation in which each human life began. At the bottom of the picture surface, blue and yellow spheres surrounded two white circles that look like ovaries joined by fallopian tubes. In the center of the painting, a wreath of ornate yellow sperm surrounded symbols for spirit and matter inside matching white eggs. Above, the reproductive organs of flowers blossomed. As the series progressed through the life cycle, circles were joined by spirals, perhaps a visual contrast between cyclical views of reality in Hinduism and a progressive view expressed in evolution. In No. 3, Youth, snails appeared. The snail’s shape mirrored the spiral form, while its physiology included both male and female reproductive organs, a hermaphroditic representation of the period before the hardened gender roles of adulthood.9

No. 7 of The Ten Largest, the third titled Adulthood, introduced the term vestalasket (vestal virgin) in legible cursive. Af Klint applied this term to herself, and it recurs throughout her work. She used it to describe the life devoted to spiritual goals, realized through painting, that she accepted when she agreed to the Great Commission.10 She might have seen the spirits use of this term in No. 7 as a reference to her own stage of life.

This small sample of symbols in af Klint’s paintings suggests the complexity of the process she faced—and we face now—in interpreting them. A more thorough treatment of what one scholar has called her “self-generating symbol system” waits for a scholar versed in the literature of nineteenth- and twentieth-century esotericism who can read the thousands of pages of notebooks that af Klint wrote in Swedish. I introduce it here to suggest possible sources of af Klint’s twenty-first-century appeal: her focus on movement between sexual unity and duality, and multiplicity; her approach to sexual difference as an ongoing problematic subject to infinite variation; and her exploration, through myriad artistic acts of creation, of the limitless permutations possible as male and female emerge from and return to a primal unity. The generation that has responded to graphic descriptions of sexual organs deployed in the abuse of power with the #MeToo movement is engaged by af Klint’s nonhierarchical depiction of sexuality. Male and female organs appear with neither vulgarity nor prudery, and often with ambiguity. Free-floating reproductive parts are simultaneously decorative and symbolic, ordinary and mysterious. A generation asserting multiplicity as an alternative to the confines of sexual binaries is ready to take flight with the playful egalitarianism of these paintings. Af Klint’s work speaks to coexisting desires to affirm and to be liberated from embodiment.

In 1908, having completed the first 128 of the Paintings for the Temple, af Klint stopped painting. Her mother had become blind and needed her care. She also met for the first time with Rudolph Steiner. Af Klint hoped he would aid her commission in two ways: first, by interpreting the meaning of the paintings, and second, by finding a place where their message could be seen. He helped with neither goal. Instead, he criticized her use of mediumship, asserting that humans could access the spiritual realm through introspection without surrendering the will to external intelligences.

Hilma af Klint, Group X, Nos. 1–3, Altarpiece (Altarbild), oil and metal leaf on canvas, at the Hilma af Klint Exhibition at the Serpentine Gallery on March 2, 2016 in London, England. David M. Benett/Getty Images for Serpentine Galleries.

When af Klint returned to the commission four years later, she no longer painted as a medium. Her spirit guides provided visions that she saw and heard, but she, not they, controlled the brush. The themes of the works were unchanged—male and female, spirit and matter, existence and nothingness—but the style now showed conscious control.11 Mediumship had freed af Klint from the restrictions of academic training. After a period of abandoning her will as an artist, she integrated this new freedom into the skills in which she had been trained. The last of the Paintings for the Temple, three large works she called Altarpiece, combined the adventurousness of her channeled works with the painterly virtuosity of her academic training.

Steiner died in 1925 without either incorporating af Klint’s work into the temple-like Goetheanum he had built in Switzerland to accommodate gatherings of his followers or suggesting an alternative venue. She then considered whether she should design her own temple where the works resulting from the Great Commission could be seen. Af Klint scholar Julia Voss found preliminary plans for the temple—a spiral ramp built around a central tower—in the af Klint papers. The temple was never built. By the time of her death in 1944, af Klint had concluded that the world was not yet ready for her paintings. She directed her heirs to keep the paintings secret for at least 20 years. Nearly 100 years would pass between the creation of Paintings for the Temple and their public reception.

Hilla Rebay (1890–1967)

Unbeknownst to Hilma af Klint, another woman painter committed to theosophical ideas would succeed in constructing a spiral temple for abstract art where af Klint’s paintings would one day hang. Hilla Rebay was the painter, and the Guggenheim Museum, designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, was the place.

Born the Baroness Hildegard Anna Augusta Elisabeth Rebay von Ehrenweisen, in Strasbourg, Hilla Rebay came from a family that had been elevated to the nobility in the nineteenth century, after succeeding in mining. Without the knowledge of her parents, the teenaged Rebay took classes with Rudolf Steiner in 1906, shortly after he began 15 years as leader of the German section of the Theosophical Society and two years before he met Hilma af Klint. Rebay trained in academic painting in Cologne, Paris, and Munich and moved on to a more modern approach to color and form by the age of 22, when she lived independently in Paris. On a visit to Zurich in 1915 she met Hans (Jean) Arp, who introduced her to painters experimenting with what she would call “non-objective” artwork—work with no reference to the world of nature, more commonly known as abstract art. Works by Vasily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, Franz Marc, Marc Chagall, and Rudolf Bauer spoke to her both aesthetically and spiritually.

Hilla Rebay, Composition I, oil on canvas, 52 1/8″ x 39 1/8” (1915). Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, the Hilla Rebay Collection.

Arp gave Rebay a copy of Kandinsky’s On the Spiritual in Art (1911), of which she would later publish an English translation. There, Kandinsky explained what attracted him and other Russian and German painters to Theosophy: access to Asian religious teachings questioning the ultimate reality of material existence. She would devote the rest of her life to participating as painter, curator, and collector in the movement to free painting from representation. Nonobjective art, she believed, would allow viewers to experience the beauty of pure thought as an alternative to the illusive world of material objects.12

Hoping to find a more receptive environment for nonobjective painting, Rebay emigrated to the United Sates in 1927. She did not find the general acceptance she hoped for, but she did find a patron: Solomon Guggenheim, a full-time art collector recently retired from his mining interests. Commissioned by Guggenheim’s wife to paint his portrait, Rebay introduced him to the work of the German and Russian painters she admired and to her view that nonobjective art provided a pathway to spiritual evolution. Rebay soon became Guggenheim’s adviser in collecting abstract art in both Europe and the United States. She toured Europe with Guggenheim, bringing him to the studios of suitable painters, and enlisting her friends to procure works for him.

Guggenheim relied on Rebay’s artistic judgment. She supplied the rationale and articulated the value of his collection. With his backing, Rebay supported artists who shared her religious understanding of abstraction. Rebay viewed each nonobjective painting as “a diagram of the soul,” because it drew on no source external to the artist.13 “Non-objectivity will be the religion of the future,” she wrote. “Non-objective paintings are prophets of spiritual life. Those who have experienced the joy they give possess such inner strength as can never be lost. This is what these masterpieces in their quiet absolute purity can bring to all those who learn to feel their unearthly donation of rest, elevation, rhythm, balance and beauty.”14 More than a style of painting, she viewed abstract art as a path to enlightenment.

Initially, Guggenheim displayed his collection in his suite of rooms at the Plaza Hotel. Then, in 1939, he opened the Museum of Non-Objective Art on 54th Street in Manhattan, with Rebay as its curator and director. In a remodeled rented space, paintings hung just above the floor, giving a sense that one could walk into each abstract plane. Floor-to-ceiling drapes of grey velour hung behind the paintings, while low couches invited extended contemplation. “The atmosphere was solemn, even pious, as if one had entered a house of worship,” one viewer recalled.15 Music by Bach and Chopin completed the experience of viewing nonobjective art. Rebay called the first exhibition The Art of Tomorrow, echoing the theme of the 1939 New York World’s Fair, “The World of Tomorrow.”

The collection continued to grow. With Guggenheim’s encouragement, Rebay began plans for a permanent home for the collection. The choice of the architect Guggenheim delegated to Rebay. After rejecting prominent European modernists, she offered the commission to Frank Lloyd Wright.

Wright and Rebay were well matched. His allegiance to organic architecture echoed hers to nonobjective art: he viewed it as a religion. And, like Rebay, he was influenced by Western appropriations of Hinduism and Buddhism. His third wife, Olgivanna Lazovich Wright, was a disciple of the charismatic, Eastward-leaning mystic, George Ivanovich Gurdjieff.16 Together, they modeled his Taliesin community on Gurdjieff’s community near Paris.

Wright was not a fan of abstract art. He coined the term “organic architecture” for design that drew on and harmonized with nature, while Rebay viewed painting as successful only when it eschewed reference to nature. Each could be preachy or impractical. Yet each was able to articulate a shared faith in the salvific character of visual experience, a faith that attained permanent form in the Guggenheim Museum.

The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. Ajay Suresh. Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0

Rebay’s vision for the museum captivated Wright. “I want a temple of spirit,” she wrote in her initial letter. Her directives included mystical language familiar to Wright through his association with Gurdjieff. “With infinity and sacred depth create the dome of the spirit: the expression of the cosmic breath itself—bring light to light! . . . Let us create a shrine to forget our personal illusions to be healingly embraced with perfected harmony by the order of spiritual reality.”17 Some architects would shy from such a client. Wright was all in.

When Wright received that letter from Rebay, he assumed the curator of the Solomon Guggenheim Collection was a man, and invited Curator Rebay to come to Taliesin and “bring your wife.” Rebay responded with an urgent entreaty that Wright come to New York during the few weeks that Guggenheim would be available to meet him. “I am not a man, but I built up this collection, this foundation,” she explained. Wright’s minor misstep evaporated amid shared enthusiasm for the museum. The preliminary contract indicated that Wright would furnish plans for the museum “according to the requirements of Curator Hilla Rebay.” They agreed early on that the building should be round and should include ramps instead of stairs.18

Wright would devote the next 16 years to the museum. According to Wright’s daughter, it was Olgivanna who selected the inverted spiral from among the final four designs Wright proposed. The seashell, the organic shape to which Wright compared his plan, was a favorite shape of Gurdjieff. Rebay’s vision of a temple to nonobjective art would become one of Wright’s most distinctive designs, designated a World Heritage Site by UNESCO two months after Hilma af Klint’s paintings came off its walls.19

Vicci Sperry (1899–1995)

Shortly after the Guggenheim opened its af Klint show in 2018, I heard from friends who had seen it that something about the huge abstract paintings reminded them of works in my home by my grandmother, Vicci Sperry, a little-known second-generation abstract expressionist. At first glance, slight evidence united works of Sperry’s with af Klint’s. The main similarity seemed to be the audacity of an obscure woman to create monumental works of boldly colored abstract art in a scale and medium often associated with masculinity. When I explained that the daring six-by-eight-foot paintings were the creation of my diminutive widowed Jewish grandmother when she was in her 70s, viewers struggled to make sense of the information.

Like af Klint and Rebay, Sperry’s path to abstraction led through religious reinvention. I witnessed steps on that path as a child, watching my grandmother paint and listening to her intermingle thoughts about art and Christian Science, though only after I was old enough to walk to her house by myself. Before that, my rationalist-Jewish parents did not permit me to be alone with her because of her recently adopted religious views. Grandma used to say that she was the best Jew in the family, in spite of being a Christian Scientist, because she read the Bible daily and gave money to Israel.

At the time, I had no idea how deeply Sperry’s artistic and religious departures intertwined. Her (mostly male) contemporaries, who became known as the New York School, looked within themselves to face their mortality and to paint the existential anguish of a war-torn world. Sperry, in contrast, looked within to face immortality. She painted the joy and assurance that knowledge revealed. Like other abstract expressionists, she sought to evoke feelings in her viewers. Unlike those artists, the feelings she sought to evoke were exclusively positive. She aspired to convey an experience of inner harmony that Christian Scientists believed healed disease and suffering by bringing the individual into congruence with the divine. I think of her work as Christian Science Expressionism.

Sperry was born in Brooklyn, New York, to Jewish immigrants who had aspired to participate in urban intellectual life before leaving Ukraine. In the United States, they joined the Society for Ethical Culture, a movement founded by a reform Jew, Felix Adler, to unite Jews with others committed to the moral betterment of society without regard to dogma or ethnicity. Sperry did not begin painting until after she had married the engineer and musician Albert Sperry, moved to Chicago, and had two children. So impressed was her teacher, the modernist Rudolf Weisenborn, with her first painting that he placed it in a show at Chicago’s Navy Pier in 1938.20

Sperry experienced the power of art to change internal experience during the devastating events of World War II. Due to go to Weisenborn’s class one bright day, she heard, “Extra, Extra, Rotterdam Bombed.” “The sun will never shine again,” she thought to herself, but she proceeded to class. “I was so grateful,” she recalled. Art “just absorbed me so that the world became kind of wonderful again. Otherwise, it seemed a terrible world. And so, art began to be that, it began to be that something where there is a wonderful world, and always will be a wonderful world.”21 Sperry exhibited works of representational modern art and soon began teaching in Chicago.

Sperry’s first solo show in New York opened in April 1948, at the George Binet Gallery on 57th Street. That was the year that Jackson Pollock first exhibited his drip paintings a few doors down at the Betty Parsons Gallery. That show would rock the art world and put Pollock and the New York School of abstract expressionism on the map. Hans Hofmann’s work was at the Kootz Gallery, in the same building as Betty Parsons.

There is no evidence that Sperry saw work by Pollock or Hofmann when she traveled to New York for her opening, but the trip convinced her that something was happening among New York artists that she needed to join. When she returned to Chicago, she began to paint differently. On a vacation in New England, she visited Hofmann’s Friday open house in Provincetown, an open critique at his Cape Cod summer school like the one he held in New York during the year.

Sperry felt an immediate affinity to Hofmann’s approach. “Every fifth word was ‘spiritual,’ ” she recalled. She may have exaggerated, but the word did appear 38 times in Hofmann’s 1948 book, The Search for the Real, the first monograph on abstract expressionism. Hofmann’s roots were in the same context of German idealism that nurtured af Klint, Rebay, Steiner, and a host of abstract painters. Like them, he viewed the artist’s intuition as the path to a deeper level of reality inaccessible to ordinary sight. He opened his first school in Munich in 1915, and he was better known as a teacher than as a painter when he arrived in the United States in 1930. Hofmann’s insistence on the spiritual nature of art was not what drew most of the avant-garde painters who flocked to his studio, but it drew Vicci Sperry.22

Sperry had been teaching art for years when she decided to study with Hofmann.23 At Hofmann’s studio she drew in charcoal. She brought paintings she made in Evanston to the open critiques on Fridays. Once, after Hofmann singled out Sperry’s paintings for praise, a reporter from the New Yorker approached her, and she assumed he would complement her painting. Instead, he asked about her hat. Dressed to take the train to Baltimore to meet her husband, Sperry wore a new spring hat bedecked with flowers and a veil. “Will you tell me,” asked the reporter, “how a person who paints a painting like that wears a hat like this?” Sperry had no response; she saw no inconsistency.24

Vicci Sperry, Untitled, oil on board, 47 1/4″ x 36″ (1935). Courtesy Diane and John Moss.

More than age and attire distinguished Sperry from the other painters. They gathered in the evenings at the Cedar Tavern for drinks (lots of drinks) and camaraderie. Sperry spent her free time in the Christian Science Reading Room in the lobby of the Tenth Church of Christ, Scientist. Located in a former factory building on MacDougal Street, around the corner from Hofmann’s Eighth Street studio, the Reading Room offered a quiet place for study. There, Sperry could access the King James Bible and Mary Baker Eddy’s Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures and other church publications. After a morning looking back and forth between her easel and a nude model, Sperry studied a faith that denied the reality of the body. Illness and suffering, she read, were symptoms of finite human vision, and could be overcome by tuning one’s mind to the infinite Mind of God. Christian Scientists viewed God not as an anthropomorphic patriarch but as a benevolent and infinitely creative force. After reading Mary Baker Eddy’s advice to maintain a constant mental focus on God’s all-encompassing perfection, Sperry returned to the studio for the afternoon still-life session.

Sperry took from Hofmann’s class something different from those who did not read Mary Baker Eddy at lunch. Hofmann and Eddy both relied on the word “spiritual,” with related but different meanings. “There are two kinds of reality,” Hofmann wrote:

physical reality, apprehended by the senses, and spiritual reality, created emotionally or intellectually by the conscious or subconscious powers of the mind. The artist’s technical problem is how to transform the material with which he works back into the sphere of the spirit. . . . Artistic creation is the metamorphosis of the external physical aspects of a thing into a self-sustaining spiritual reality.25

Mary Baker Eddy saw physical reality as a product of “mortal mind,” the limited human understanding based on sense perception that inevitably resulted in illness and suffering. Spiritual reality, in contrast, reflected “Divine Mind,” the unbounded reality beyond materiality.

After two and a half years, Sperry concluded her work at Hans Hofmann’s studio. She marked the transition with two dramatic actions. In November 1955, she became a member of the First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston, Massachusetts, the Mother Church of Christian Science. Joining did not require a trip to Boston. New Christian Scientists often joined the Mother Church before a local congregation, an expression of gratitude for Christian Science and identification with its goals.

The timing of Sperry’s membership in the Mother Church suggests that the gratitude she felt for her new religious principles coincided closely with her transition from figurative to abstract art. A few weeks after she joined the Mother Church, she purchased a large painting by Jackson Pollock, which allowed her to take the vibrant influence of New York home to Evanston. The purchase was an assertion of artistic independence, a daring expenditure of the then phenomenal sum of $3,000. Though Life magazine had already suggested that Pollock might be “the greatest living painter in the United States,” his work remained controversial. When Sperry proposed the purchase to her husband, he asked if she loved the painting. “No,” she said, “I do not love it. But I need to learn from it.” Neither Sperry nor the dealer, Sydney Janis, knew that Search would be Pollock’s last painting. A few months later Pollock, drunk, drove into a tree, killing himself and one of his passengers.

Vicci Sperry, Child with Red Face, oil on canvas, 52″ x 40” (1966). Courtesy Diane and John Moss.

The Sperrys moved to Los Angeles in 1960, where they hung the Jackson Pollock in their new home overlooking the Santa Monica Bay. The pervasive sunlight of Southern California infused Sperry’s new abstract works. Her husband’s progressing cancer sealed her commitment to Christian Science healing. Like many of those who worked on the development of the nuclear arsenal during and after World War II, Albert Sperry, 60 years old, succumbed to the impact on his cells of the unseen reality of radiation. Following her husband’s death, Sperry became a Christian Science practitioner, a professional minister of healing. From 1964 to 1967, she was listed by the church as a practitioner available to meet with those in need of healing. Through prayer, supportive conversation and text study, practitioners attempted to help sufferers overcome errors in thought that separated them from complete harmony and to align their thoughts instead with the divine perfection inherent in every being.

Practitioners were not permitted to have other employment. Church records indicate that Sperry left the public practice of Christian Science after three years because she “had other work.”26 In addition to painting and teaching, she was writing a book illustrated by her abstract paintings. The Art Experience, published in 1969, offered an approach to art as a quest for harmony. Rather than the Christian Science Church, she described the experience of creating art as the location of the human pursuit of transcendence. “Art,” she explained, “is the joyous and spontaneous evidence of man’s capacity to express his deep feelings for beauty, order, life and love.” To become an artist was to become a vehicle for truth. “Prepare your attitude, but not the expression,” she wrote. “We have to wait and listen to that which speaks to us from the universal.”27

Art was Sperry’s topic, but her words could have come from a spiritual counselor. “Have such inner dedication that your individual thinking cannot be dampened,” she urged the developing artist. “We have ideas. Ideas are thoughts formed with beauty and principle that become channeled and complete as we work with dedication. . . . We do not force ideas—we allow them to come. They stem from infinity.”28

I remember watching Vicci enact these words as she created the paintings that reminded my friends of works by Hilma af Klint. Standing before a huge canvas leaning against the wall of her studio she would pause, paintbrush in hand, calmly regarding the painting-in-formation. Her breathing slowed while she waited for inner peace. Then she would reach toward her cart of acrylic paints, dip the brush into an open jar, and wipe it on the rim. Next she would extend her arm, sometimes above her head, until her brush touched canvas. In a slow but spontaneous gesture, she moved the brush across its surface. Then she repeated the sequence until the thought was complete. Finally, she would step away from the painting and take in what she had done.

Women Artists on the Path to Abstraction

How should we think about these three artists amid calls to rewrite the history of modern art in light of previously ignored women? Does the work of af Klint, Rebay, and Sperry suggest an alternative, more inclusive history of modern art? For a final point of comparison, let’s contrast their stories with a particularly successful effort to place women at the center of the story of abstract painting: Mary Gabriel’s Ninth Street Women: Lee Krasner, Elaine de Kooning, Grace Hartigan, Joan Mitchell, Helen Frankenthaler: Five Painters and the Movement that Changed Modern Art.29

Gabriel retells the history of abstract expressionism radiating from the lives of five vibrant exponents. The result is a riveting reevaluation of the movement that established the artistic independence of the United States, gently suggesting that there could have been no abstract expressionism without its female protagonists. Lee Krasner, we learn, was a leader among New York artists whose avant-garde experiments in technique predated those of Jackson Pollock. Elaine de Kooning married her teacher, Willem de Kooning, but maintained artistic and personal independence. Her generous spirit provided connective tissue that helped the New York School cohere. They and the other Ninth Street Women eschewed double standards. They drank, smoked, lived in poverty, were tormented by creative challenges, enjoyed sexuality, and experimented with abstraction along with their male peers, and often ahead of them.

The work of af Klint, Rebay, and Sperry requires a different arc of interpretation. They walked paths to abstraction far afield from painters for whom abstract art reflected the existential crisis of a heroic individual, an interpretation often applied to famous male artists like Pollock and de Kooning. A cursory glance shows that the work of af Klint, Rebay, and Sperry was emphatically modern. A deeper look may prompt us to rethink the notion that individual choice forms the core of a modern sensibility. It may also suggest that histories of feminism should include figures for whom spiritual liberation is more important than sexual freedom as a step toward unbridled artistic expression. Such histories should make room for af Klint, Rebay, and Sperry, as well as for the Ninth Street Women.

Abstract painting, for af Klint, Rebay and Sperry, set a course beyond material reality toward a reality that could not be perceived by the senses. For each one, the quest to use physical materials to convey the immaterial, to use the finite to convey the infinite, was both a spiritual and an artistic practice.30

Each labored for self-expression to become a vehicle for spiritual knowledge. And each painted past the limits of gender by spiritualizing the body: af Klint by depicting gender binaries as temporary and ultimately resolvable, Rebay by eliminating the body and gender as subjects for art, and Sperry by removing the boundaries of the body to convey human unity with the divine. Each viewed art not as an end in itself but as a way that divine truth could become perceptible to human beings, using modern methods to bridge modern and timeless concerns.31

Notes:

- Roberta Smith, “ ‘Hilma Who?’ No More,” The New York Times, October 11, 2018. Shirine Saad, “What Can the Museum World Learn from Hilma af Klint?” Slate, May 1, 2019.

- R. H. Quaytman, in The Legacy of Hilma af Klint: Nine Contemporary Responses, ed. Daniel Birnbaum and Ann-Sofi Noring (Moderna Museet, 2013).

- See, for example, Iris Mueller-Westerman with Jo Widoff, Hilma af Klint—A Pioneer of Abstraction (Moderna Museet, 2013); Daniel Birnbaum et al., Hilma af Klint: Seeing Is Believing (Serpentine Galleries, 2017); and Tracey Bashkoff, Hilma af Klint: Paintings for the Future (Guggenheim Museum, 2018).

- Rudolf Steiner, Theosophy, trans. Catherine E. Creeger, (Anthroposophic Press, 1994), 97–98.

- Tracey Bashkoff, “Temples for Paintings,” in Hilma af Klint: Paintings for the Future, 19–20.

- H. P. Blavatsky, The Secret Doctrine, vol. 1, ed. Boris de Zirkoff (Quest Books, 1993), 469.

- Ibid., 379.

- Julia Voss, “Hilma af Klint and the Evolution of Art,” in Hilma af Klint: Painting the Unseen (Serpentine Gallery, 2016), 29.

- The Ten Largest #3, Youth is the opening image for this article. The Ten Largest #1, Childhood can be viewed in the online version of this article at bulletin.hds.harvard.edu.

- Johan af Klint, personal communication to author, February 14, 2019.

- Bashkoff, “Temples for Paintings,” 24. Julia Voss, “The Travelling Hilma af Klint,” in Hilma af Klint: Paintings for the Future, 60.

- Joan M. Lukach, Hilla Rebay: In Search of the Spirit in Art (George Braziller, 1983), 9, 14.

- Karole Vail, “Rhythmic Delight: A Quest for Non-Objectivity,” in Art of Tomorrow: Hilla Rebay and Solomon Guggenheim (Guggenheim Museum, 2005), 133.

- Lukach, Hilla Rebay, 96.

- Robert Rosenblum, “The Music of the Spheres,” in The Museum of Non-Objective Painting, ed. Karole Vail (Guggenheim Museum, 2009), 220.

- Robert C. Twombly, “Organic Living: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Taliesin Fellowship and Georgi Gurdjieff’s Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man,” The Wisconsin Magazine of History 58, no. 2 (December 1, 1974): 126–39.

- Hilla Rebay to Frank Lloyd Wright, June 23, 1943, as quoted in Lukach, Hilla Rebay, 183, 186.

- Lukach, Hilla Rebay, 183–85.

- Roger Friedland and Harold Zellman, The Fellowship: The Untold Story of Frank Lloyd Wright and the Taliesin Fellowship (Harper Collins, 2006), 393.

- Victoria Hess married Albert F. Spitzglass in Brooklyn, NY, in 1923. With other family members, she adopted the Americanized last name “Sperry” around the time she started painting in the mid-1930s.

- Vicci Sperry, interview by author, 1979.

- Vicci Sperry, manuscript autobiography, 114, author’s collection.

- Her husband was surprised, because she had said there was no one she could study with anymore. They worked out a plan that allowed her to spend two weeks each month in New York, traveling on her husband’s ticket while he attended to business in Baltimore.

- Sperry, manuscript autobiography, 112.

- Hans Hofmann, Search for the Real and Other Essays (Phillips Academy, 1948), 40.

- Michael Hamilton (executive director of the Mary Baker Eddy Library), personal communication to author, December 15, 2014.

- Vicci Sperry, The Art Experience (Hennessey & Ingalls, 1969), 28, 18.

- Ibid., 34.

- Mary Gabriel, Ninth Street Women: Lee Krasner, Elaine de Kooning, Grace Hartigan, Joan Mitchell, Helen Frankenthaler: Five Painters and the Movement that Changed Modern Art (Little Brown, 2018).

- I am indebted to art historian Lucy Kent for this insight. See Lucy Kent, “An Act of Praise: Religion and the Work of Barbara Hepworth,” in Barbara Hepworth: Sculpture for a Modern World, ed. Penelope Curtis and Chris Stephens (Tate Publishing, 2015), 37–49.

- With gratitude to Tracey Bashkoff, David Horowitz, Johan af Klint, Liza Braude, Nancy Cott, Susan Reverby, Carla Kaplan, Tracy Wall, Ailie Posillico, Esther Adler, Diane Moss, Carol Moss, Susan Besse, Michael Hamilton, David Lubin, Peggy Burns, and Phil Deloria, for guidance, inspiration, assistance, and friendship while writing this essay.

Ann Braude is the director of the Women’s Studies in Religion Program and Senior Lecturer on American Religious History at Harvard Divinity School. She is the author of Radical Spirits: Spiritualism and Women’s Rights in Nineteenth-century America (2nd ed., Indiana University Press, 2001) and Sisters and Saints: Women and American Religion (rev. ed.; Oxford University Press, 2007), and she has published many articles on women in Judaism, Christian Science, and American religious life.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.

Thank you. Thank you so much. Shared this with my Arts Appreciation Group. Would have love to have had this available for my students as I did 25 years teaching in all female schools. We progress, we move on. email shows up as Upper Case – should be danielpeterdaniel@gmail.com – website peterdaniel.org.uk