Featured

Only Connect: Networked Christianity in the Digital Age

Illustration by Daniel Liévano

By David N. Hempton

Only Connect! . . . Only Connect the prose and the passion.

Personal relations are the important thing for ever and ever, and not this outer life of telegrams and anger.

—E. M. Forster, Howards End (1910, chaps. 22 and 19)

E. M. Forster’s novel about the developing connections between the Schlegel and Wilcox families—respectively, the worlds of personal relationships, arts, and culture, and the worlds of business, capitalism, and pragmatism—anticipates by over a century some of the important questions about the impact of revolutionary changes in global connectivity in the age of the internet and its consequences for the history of Christianity. We started this lecture series with some reflections from Niall Ferguson’s The Square and the Tower, which he bookends with two revolutions: print in the sixteenth century and the internet and social media in the late twentieth century. “The global impact of the internet,” he writes, “has few analogues in history better than the impact of printing on sixteenth-century Europe. The personal computer and smartphone have empowered networks as much as the pamphlet and the book did in Luther’s time.”1 He also notes some important differences. The networking revolution has been faster and more geographically extensive; second, it has increased inequality and concentrated fabulous wealth in fewer hands; and third, the printing press disrupted religious life before anything else, whereas the internet disrupted commerce first, and in Ferguson’s opinion has disrupted only one religion, Islam.

Ferguson justifies this assertion by references to the Jihadist networks constructed by Islamic extremists, but it is clearly not the case that Christianity has escaped impact from the internet revolution; the question is how, and more broadly, how is Christianity changing in the age of social media and international connectivity? Attempting answers to these questions is more complicated than assessing the impact of print on religious change in the sixteenth century, at least in part because we are currently living through the digital media revolution and we do not yet have the benefit of perspective and accumulated research. While acknowledging those realities, the aim of this lecture is to begin answering these questions by posing three subsidiary questions: What social and cultural changes were already underway in the decades immediately preceding the internet revolution that have a direct bearing on the generations most affected by that revolution? What does the preliminary evidence reveal about the impact of new technologies and social media on the beliefs, practices, and “lived religion” of Christian communities, organizations, and denominations? Finally, to what extent has the internet helped develop global religious networks in which the directional flows of power and influence have begun to change from a North to South trajectory to a South to North one?

Any answer to the first question has first to grapple with a vast and growing literature on secularization across the Western world.2 In a recent survey of that literature, Hugh McLeod states that

Historians and sociologists agree that the major religious changes in most Western countries included a decline in churchgoing and in participation in rites of passage; a weakening of religious socialisation; questioning of official church teaching, especially on sexual ethics; and an increasing tendency to see society as “pluralist,” or even “secular,” rather than “Christian.”3

This consensus, such as it is, does not extend to explanations for how, why, and at what speed this secularization—or perhaps, more accurately, dechristianization—has happened from region to region and country to country. Among the most persuasive are declining rates of generational transmission (partly as a result of greater female emancipation and participation in the workforce), the increasing role of the state in providing services previously offered by religious organizations, the primary secularization of young, working-class men, the erosion of rural pockets of strong religiosity under pressure from modernizing trends, and the role of churches themselves through contributing to their own demise by liberalizing their theologies and participating in cultural changes that undermined their own claims for attention.4

The complex of cultural changes we associate with the long 1960s had already undermined generational transmission of faith traditions, promot[ing] concepts of individual freedom from traditional authorities, including churches.

McLeod and I have tried to grapple with the comparative transatlantic dimensions of secularization in another book, but for the present purposes, it is less important to agree on the how and why of secularization than on the rough consensus about what McLeod laid out in his review article, “Western Religion in the Long 1960s,” and in another suggestive, as-yet unpublished essay, “The Register, the Ticket and the Website.”5 Together they assert that several decades before the onset of the internet revolution and the proliferation of social media, the complex of cultural changes we associate with the long 1960s had already undermined generational transmission of faith traditions, promoted concepts of individual freedom from traditional authorities, including churches, and encouraged younger cohorts to construct their identities not through family inheritance or membership of local faith communities but by self-actualizing individual choices freely made. All of these changes were arguably reinforced and accelerated by the information revolution of the past 30 years.

There is already a formidable literature in existence about how the internet has impacted social norms or how religious traditions both exploit and suffer from digital technologies, or about the challenges of negotiating faith and theology under new conditions.6 Some suggest that the internet and mobile technologies have effectively created a new social operating system labeled “networked individualism,” at the center of which are autonomous individuals reaching out and interacting with others in multiple different social circles in fast-moving and complex patterns. This social system encourages fragmented networks of multiple social circles rather than deep investment in any particular community or congregation based on a preassigned affiliation of some. This is analogous to the concept of differentiation in secularization theory.7 It is easy to see how this more fragmented structure managed by autonomous individuals, rather than by inherited familial or community faith traditions, effectively accelerates the changes already operating in post-1960s Western culture identified by scholars of secularization.

The fast-growing body of work on the impact of digital technologies on Christianity has identified four areas worthy of further analysis. The first relates to individuals and their search for online community, the second relates to how well religious institutions are adapting or not adapting to new informational technologies, the third focuses on challenges to traditional sources of authority and control, and the fourth relates to overall cultural assessments about how this communications revolution is altering the way in which Christian faith traditions function or do not function in the twenty-first century. Unsurprisingly, there are vigorous disagreements within each of these categories.

In her in-depth analysis of three quite different kinds of online religious communities, the Community of Prophecy, the Online Church, and the Anglican Communion Online, Heidi Campbell identified six attributes of online community that individuals were searching for: relationship, care, value, connection, intimate communication, and shared faith.8 These are not substantially different from the attributes most desired from offline religious communities, but the online version confers more individual control, fewer geographical or temporal limitations, and more scope for individual spiritual experimentation and self-actualization. Moreover, many of those engaged with online religious communities saw them as supplemental rather than as necessarily binary alternatives to local faith communities. Religion online serves a variety of different functions, from a worship space to a prayer network and from a support or identity network to a study or service portal. Equally variegated were the positive and negative poles of digital communication, which could promote deep friendship and spiritual connection, on the one hand, and spamming, flaming, stalking, and inappropriate counseling and power maneuvers, on the other. Most offline religious communities have structures of governance and mechanisms for exercising discipline, while most online communities are more unregulated and more vulnerable to rogue or destructive actors. Individuals certainly have a wider range of online choices available to them, both locally and globally, but the data suggest that far from producing a more engaged transnational and interfaith pluralism, digital technologies may in fact reinforce a form of selective tribalism as online searchers gravitate to what most interests them. Ironically, the capaciousness of the web can easily result in the narrowness of the sect or the site.

twitter.com/Pontifex

A similar ambiguity about the pros and cons of online faith attachments for individuals is also the case for religious institutions. The survey data indicate that church leaders have steadily embraced blogs, podcasts, and social media as adjunct tools in their various ministries. Having said that, some traditions seem to have adapted better than others. Figures from the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association and Global Media Outreach show that conversionism plays well on the internet, while traditions more oriented around ritual and community find it harder to adapt.9 For example, Campbell opens her latest book with a story about an application developed by an American software company to help Catholic penitents prepare for the sacrament of confession. This app had the blessing of some American Catholic leaders but got the attention of the Vatican, which ruled that although the app was acceptable as a preparatory guide, it could not be a substitute for the embodied act of confession conducted by a priest.10 In fact, the Vatican has been remarkably proactive in engaging with digital media. The Roman Catholic Church was the first religious denomination to launch its own website in 1996; it launched its own YouTube channel in 2009 and has employed Twitter, Facebook, and its own online news portal to get across its message.

As churches and religious communities have sought to maximize social media, they have encountered new issues of authority and control. In particular, Campbell has shown that a new category of leaders whom she calls Religious Digital Creatives has emerged. Whether digital entrepreneurs using advanced algorithmic skills, digital spokespersons charged with effectively communicating a church’s mission, or digital strategists negotiating online and offline authority structures within religious institutions, there is no denying that a powerful new group of specialists has emerged whose authority is based more on their digital expertise than their pastoral or theological credentials.11 How that authority is exercised and under what constraints varies from congregation to congregation and crucially with the size of the religious enterprises. Unforeseen events such as the COVID-19 pandemic and the jet propulsion of Zoom gatherings further reinforced the dependence of churches and faith communities on the expertise of tech specialists. Faith communities, as with other kinds of institutions responsible for transmitting knowledge and information, will have to reckon with both the short-term and long-term impacts of the pandemic on the delivery of their mission. Virtual events often have much higher numbers of registrants but cannot reproduce the in-person convivialities of fellowship. It is also important to recognize that trends which seem to be unidirectional and inevitable may not turn out to be so. For example, a decade ago it seemed that the trend towards e-books overtaking physical books, with the consequent decline of real bookstores, was irreversible, but more recent data indicate that most people still like browsing in bookstores and reading from material books. It remains to be seen whether digital forms of religious community will inexorably erode in-person gatherings.

None of the three questions posed earlier about the impact of digital media on faith communities have unambiguous answers, but perhaps the most difficult of all is the question about the overall cultural impact of social media on how churches function or do not function in these early decades of the twenty-first century. My main argument is that there is something of a continuity between religious dimensions of the cultural and social changes of the long 1960s and the impact of social media over the past three decades, which have accelerated those changes.12 Sometimes new networks are superimposed on preexisting networks and derive their impetus from them. For example, Daniel Vaca’s investigation of evangelicalism as a “commercial religion” shows how the huge industry of religious book publishing and consumption adapted to new realities when brick-and-mortar bookstores were forced to close under pressure from new digital dynamics. “If bookstores typified the old evangelical economy,” writes Vaca, “the internet has been the heart of the new economy,” enabling best-selling authors like the Californian pastor Rick Warren “to engage their publics more directly than before, cultivating their personal brands.” Warren was able to generate a network of more than 6,000 churches from 80 denominations in 12 countries, which enabled his publisher to sell 14 million copies of his book in just a few years.13 Others have suggested that the growth of new media, especially within younger cohorts, has eroded the Christian Right’s political ascendancy within American evangelicalism, with new emphases on climate change, protection of the environment, social and economic justice, and gay rights. With pardonable exaggeration, one recent study concludes that “The internet has completely redrawn the global landscape within the space of a generation, creating a much more interconnected world and fostering virtual communities where online users are able to engage in debate and faith exploration, freely exchange ideas, and even form new organizations, interest groups, and religious communities.”14 But there is also a darker side to these developments. A recent article in the New York Times, “Christian Prophecy Movement Is Hit Hard by Trump’s Defeat,” states that social media have facilitated a bogus prophecy industry within American populist evangelicalism that is full of failed predictions about the results of the 2020 presidential election, and shearing off into dangerous conspiracy theories such as those articulated by QAnon.15

Saddleback Church, led by Pastor Rick Warren, celebrated its 35th anniversary at the Angel Stadium in Anaheim, California at which some 20,000 people were present. Screen capture from Saddleback Church video

If the digital age is opening up new possibilities for long-standing religious traditions like Roman Catholicism and evangelical Protestantism, it is also facilitating new forms of “spiritual-but-not-religious” expressions among those who have come of age in the internet era. Aware that millennials are less religiously affiliated than previous generations and that various American surveys of religiosity have identified the “nones” or religiously unaffiliated as the fastest-growing category in the American religious landscape, two Harvard Divinity School students recently set out to interrogate these categories. What they discovered is that “millennials are flocking to a host of new organizations that deepen community in ways that are powerful, surprising, and perhaps even religious.” They looked at 10 of these organizations, everything from fitness clubs to social transformation organizations, and discovered that they had six things in common: community (valuing and fostering deep relationships that center on service to others); personal transformation (making a conscious and dedicated effort to develop one’s own body, mind, and spirit); social transformation (pursuing justice and beauty in the world through the creation of networks for good); purpose finding (clarifying, articulating, and acting on one’s personal mission in life); creativity (allowing time and space to activate the imagination and engage in play); and accountability (holding oneself and others responsible for working toward defined goals).16 Unsurprisingly, they concluded that the organizations they surveyed “serve disproportionately affluent, urban, educated, and white populations,” perhaps those populations that are vacating the Protestant mainline and more traditional Catholic congregations at the fastest rates. Nevertheless, their most obvious conclusion is that many of the functions supplied by these organizations mirror quite closely, albeit with different descriptive language, those traditionally associated with religious congregations, thereby reinforcing their intuition that the category of “spiritual but not religious” is one that has particular appeal to younger generations of urban Americans.

A second example comes from a network constructed by one of the above investigators. Beginning with a weeklong set of movie evenings based on the Harry Potter films, he and a friend effectively built up a “mini congregation” before launching “Harry Potter and the Sacred Text” as a podcast that now has over 22 million downloads and 70,000 weekly listeners. Based on techniques of disciplined sacred reading, this virtual community helps people connect with themselves, with others, and with issues in the wider world. Just how deep and meaningful these personal connections become is illustrated in some of the personal correspondence reproduced in a recent book on the power of ritual that aims to reapply ancient wisdom on the importance of ritual to everyday practices.17 Once again, wisdom traditions rooted in religious traditions are transmitted in modern idioms through networks enabled by digital media. This is networked individualism in action. This conclusion fits into a pattern of sociological research on the interrelationship of religion and media based on extensive interviews across different religious and social categories. “Our interviewees,” concludes one such study,

live in a post-Enlightenment, secularized (using a conditional definition of that term, of course), late-modern world, defined by personal autonomy, the self, and rational and reflexive modes of cultural practice. At the same time, though, they can be said to be involved in a process of “re-naturing” the religiosity or spirituality of these practices, building religion and spirituality into things through their rediscovered interest in invigorating social and cultural experience with these dimensions.18

This does not normally constitute a re-enchantment of the world into mystical religious categories, but it does not bode well for traditional religious authorities whose “pulpits” are decentered by the democratization of mass media. On the other hand, some cultural analysts have identified a connection between cyberspace, immateriality, and spirituality. In these accounts the digital domain, because of its evident immateriality, carries with it the possibility of “religious valorization” or of reimagining “sacred space” because it is separate from the physical realm and can be the subject of millenarian and spiritual fantasies.19

The digital domain . . . carries with it the possibility of “religious valorization” or of reimagining “sacred space.”

What then happens, to use a recent book title, when religion meets new media?20 The answer, it seems, is predictably ambiguous. On the one hand, new media offer mechanisms and opportunities for more extensive proclamation of core beliefs, national and global networking, and community building via shared online rituals, while on the other they may expose the faithful to inappropriate content, weaken traditional authority structures, and place more power in the hands of dedicated and tech-savvy individuals with an agenda.

One recent study of networked Christianity in the United States makes a much bolder claim that the future of Christianity in the United States and beyond is being changed forever. Locating their study of Independent Network Charismatic (INC) Christianity within the context of large-scale social changes, including globalization, the digital revolution, and the challenge to religious bureaucracies, Brad Christerson and Richard Flory, argue that traditional denominational Christianity is in terminal decline in the United States. The future belongs to networks of independent churches that emphasize direct supernatural engagement, innovative financial and marketing strategies, and new digital communications technologies. Paralleling similar changes in the organization of global capitalism, INC leaders have realized that they have “more freedom, flexibility, and lower overhead by organizing themselves into networks rather than by building formal organizations. They can maximize their influence and minimize their costs by going directly to the ‘consumer’ with their ‘product’ rather than delivering the product through a formal congregation or denomination.”21 Organized around networks of charismatic apostles, INC churches have significant competitive advantages over denominational Christianity in terms of the freedom to experiment and the raising of revenue. Instead of relying on the notoriously ineffectual “plate collections” and voluntary donations from congregants, INC churches raise the bulk of their income from web-based media sales (music, DVDs, books, web content), tuition, conferences, external donations, and monetizing their property assets. They also reduce expenditure on items that conventional churches must fund to build and sustain congregations, such as staffing, program management, property maintenance, and so on. In essence “the typical congregation is a high overhead, low-revenue stream model,” while the INC churches “have shifted towards a ‘pay for service’ model in which followers pay for a particular product.”22 As any business major will tell you, this model expands the customer base, refines the product, and generates a lot more money. All of this is facilitated by the internet, which acts as a delivery platform, an advertising medium, a pay-per-view revenue stream, a virtual community of believers, and communication flows “not just from follower to leader and back, but horizontally among nodes in the network.”23 However, not everything is rosy in the INC garden. Failed prophecies, lack of deep in-person community, financial and leadership scandals, and lack of a compelling overall social vision have all surfaced in the INC world, which is dominated by predominantly male prophets.

Whatever is in store for INC churches, Christerson and Flory propose four hypotheses about the future of Christianity itself, based on their observations of INC networks: religious belief and practice will become increasingly experiential; religious authority will devolve more to individuals than institutions; religion will become more orientated to practice than theology; and individuals will increasingly customize their own beliefs and practices.24 Time will tell if these changes are inexorable, but there is no doubt that they are currently happening.

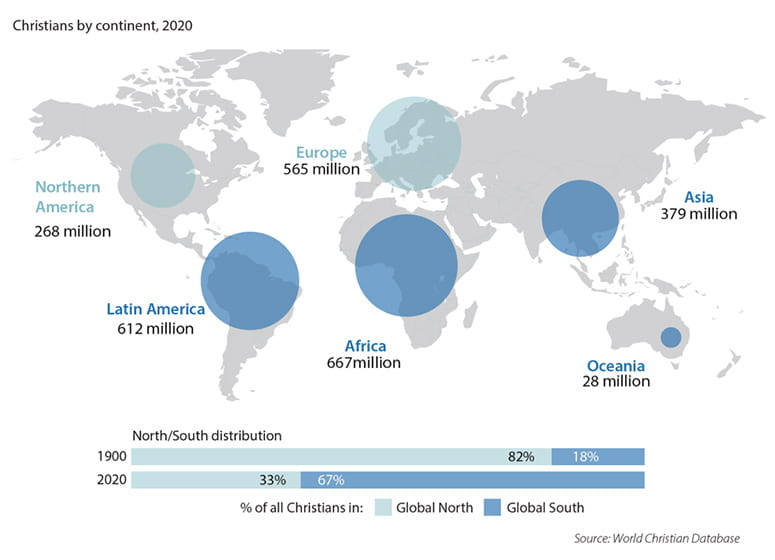

To recap, the argument presented so far in this lecture is that the profound social and cultural changes of the 1960s and 70s, which historians and sociologists have analyzed within the framework of secularization and differentiation, were accelerated and redirected by the digital revolution and globalization. I have looked at the impact of new social media on religious belief and practice and on religious institutions. The four main conclusions arrived at by Christerson and Flory, though directly applicable to the INC churches in the United States at the center of their investigation, have wider salience for the future of Christianity, not only in the United States, but around the world. Consequently, these changes also need to be placed in the context of a dramatic shift in the distribution of world Christianity.

Christians by continent, 2020. Todd M. Johnson and Gina A. Zurlo, eds. World Christian Database (Leiden/Boston: Brill, 2022).

According to some estimates, some 60 percent of the roughly two billion Christians in the world are now located in the global South (Latin America, Africa, and Asia), a figure that on current projections may rise to 75 percent of around three billion Christians by 2050. But the shift is not in numbers alone. In a recent book titled A Moving Faith: Mega Churches Go South (2015), the writers attempt to identify common themes over a wide global geography.25 These include the adaptability of charismatic/Pentecostal supernaturalism to indigenous cultures; the transmission through networks of common tropes such as prosperity, healing, and material merchandizing of religious products; the marketing, branding, and mediatization of faith; the attention to producing seeker-friendly, spatial environments for younger cohorts; a greater, if still limited, empowerment of women; and a growing interest in influencing wider social and political reforms. What is striking about these developments is how networked they are in “a complex system of transnational interactions” promoted by the well-known instruments of globalization.26

In a study of one particular nucleus at the center of many of these changes, the prosperity gospel, Kate Bowler writes:

The development of digital media only accelerated the breathtaking pace of transnational communication. The prosperity gospel was obsessed with modernity and delighted in exploiting the latest methods of communication. As congregations, audiences, and leaders in disparate locations became increasingly interactive and integrated, the prosperity gospel rapidly spread as a global phenomenon.27

For those able to plot and document the transnational flows of influence and impact, “the key was networking and point-to-point contact.” Bowler adeptly shows in her many networking charts of individuals, conferences, and locations just how thoroughly networked this prosperity gospel movement was and is in the lives of leading proponents like Oral Roberts, Kenneth Hagin, Carlton Pearson, and Marvin Winan.28

The principal means of dissemination of prosperity gospel theology has been through megachurches, first in the United States and now around the world. The cultural origins of the megachurch phenomenon in the Anglo-American world—what one historian has called “Big Religion”—has a long history around urban concentrations of population, the evangelical imperative to ceaseless evangelism, and robust ideologies of growth and expansion built around faith in a divine command to be faithful and multiply.29 More of a heterogeneous family of religious traditions than a straightforward teleology, megachurches have been associated with gilded age popular preachers, social gospelers, revivalistic conservatives, Baptist fundamentalists, positive thinkers, and, increasingly, Pentecostal prosperity exponents. A primarily Anglo-American concept has now gone global and the global South is reexporting it back to the Euro-American world through population migrations, church-planting, and a deliberate mission strategy. Its underpinning nucleus is a theology of Holy Spirit–inspired “bigness” as demonstrable and irrefutable evidence of divine blessing. In this way, the size of churches and the size of their evangelistic ambition are sanctified as faith in the power of the gospel message and of the enabling of the Holy Spirit.

Redeemed Christian Church of God. Lagos, Nigeria. Robin Hammond/Panos Pictures

The main growth hubs are cities in sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America, the Philippines and South Korea, home of the world’s largest church. Shared success stories and business models, international church-growth conferences, circulating popular preachers, and ubiquitous praise music travel along the global networks. All gets amplified by a sophisticated deployment of social media, including television and radio, satellite TV and webcasting, websites, and music and tape ministries. The scale is sometimes breathtaking. For example, in Lagos, Nigeria, two neighboring churches, the Redeemed Christian Church of God (RCCG) led by Enoch Adeboye and David O. Oyedepo’s Living Faith Church Worldwide (LFCW), popularly known as the Winner’s Chapel, have impressive multipurpose sites and huge auditoriums. Adeboye’s Redemption Camp and Oyedepo’s Canaanland have all the facilities of a modern small town, and in the spirit of global extension, another Redemption Camp is being planned for Floyd, a small town in northern Texas. There are many other megachurches with similar ambitions in Nigeria, and Nigerian pastors now lead the biggest single church in Western Europe, the Kingsway International Christian Center (KICC), based in London, which is affiliated with the RCCG, and a prominent megachurch in Kyiv in Eastern Europe. The missionary aspirations of these churches are equally grand. The RCCG aims to plant churches within five minutes’ walk or driving distance in towns and cities throughout the world, and the Winner’s Chapel has a network of over 300 churches in Nigeria and in over 63 cities throughout Africa, the UK, and the USA.30 The vision is to take the divine presence to all the nations of the world, thereby demonstrating the power of the Holy Spirit.31 The possibilities are thought to be as endless as the spiritual power they embrace.

There is now a formidable African Christian diaspora in Europe and North America made up of three major strands: branches of churches with mother church headquarters in Africa; churches formed directly by African migrants themselves; and “a proliferation of para-churches, prayer/fellowship groups and supportive or interdenominational ministries.”32 These African diaspora churches are often situated at nodal points of migration networks and self-consciously exploit network technologies in pursuit of their mission. They also build ecumenical networks of churches, such as the Council of Christian Churches with an African Approach in Europe (CCCAAE) and the Scottish Council of African Churches (SCOAC), and promote networking through shared pulpits, expensive communication ventures, and large-scale international conferences. In this reverse pattern of migration and mission, not everything is plain sailing. Evangelistic strategies often morph from African-inspired interpersonal connections into more Western models of mass communication, and there are well-known tensions between churches with different lineages, whether Afro-Caribbean, African American, or African.33 The African Christian diaspora reflects and exploits transnational movements of peoples propelled by globalization and novel communications media. Given current demographic trends, the African imprint on world Christianity, even in Europe and the United States, is going to increase in the century ahead.

One aspect of global networks of religious transmission that sometimes gets too little attention is music. The acknowledged primary worldwide hub, or node, in this network is the Hillsong Church in Sydney, Australia. Founded in 1983, Hillsong was once affiliated with the Australian Assemblies of God but is now Australia’s largest independent, charismatic megachurch. In the words of one marketing expert, Hillsong Church “de-religionized organized religion into a spiritual product with its own brand.”34 Its best-selling product is its music label. Hillsong’s praise and worship music has been recorded on dozens of albums, many of which have achieved gold or platinum status. Hillsong praise music has found its way into churches throughout the world and in 2012, through the release of The Global Project, had a collection of its songs translated into nine languages. Hillsong Church now has five campuses in Australia, an extensive family of lucrative brand names, and satellite locations in London, Paris, Kyiv, Cape Town, Stockholm, Moscow, Konstanz, New York, Amsterdam, and Copenhagen.35 In an insightful analysis of the worship experience of the London branch of this transnational network, Tom Wagner states that this kind of congregational music “is both a media object and a form of media” that operates in a convergent and “participatory culture . . . in which the lines between producer and consumer are blurred, where information is no longer distributed, but rather circulated in networks that (re)shape, (re)make, and (re)mix it to serve the personal and collective interests of its participants.”36

Information is no longer distributed, but rather circulated in networks that (re)shape, (re)make, and (re)mix it.

Ethnomusicologists tell us that music is a cultural system that helps mold human thought and emotions. In the history of Christian and congregational music, hymns and praise songs express personal relationship with the divine, create structures of meaning, and transform theological understandings. Whether it is the Lutheran hymns of the Protestant Reformation, the Wesleyan hymns of the Evangelical Revival, or the praise songs of Hillsong, the setting of words to music for congregational participation is perhaps the most influential and undervalued aspect of the transmission of religious meaning to mass audiences. In Hillsong praise music, as with Charles Wesley’s hymns in an earlier era, there is a heavy use of personal pronouns in which “the intimacy of you and me introduces a spirit of closeness, warmth, and approachability that is meant to communicate difference from the traditional stereotype of religion that denotes doctrines, authority, and rules.”37

The worldwide dissemination of Hillsong praise music is somewhat reminiscent of the importance of Wesleyan hymns in the Evangelical Revival, but there are also some important differences. Although the Wesley brothers certainly used the best distribution networks available to them in disseminating the Collection of Hymns (1780) primarily to the people called Methodists, and although they appropriated popular tunes for added emotional cogency, John Wesley also exercised ruthless editorial and theological oversight and gave clear instructions about how, when, and where hymns should be sung to minimize the risk of emotional self-indulgence.38 Through the application of new technologies and sophisticated international distribution and marketing networks, the Hillsong phenomenon is more self-consciously a brand, a product, and an experience. The medium and the message are still indissolubly linked, but the whole Hillsong enterprise is even more indelibly marked by the cultural forces shaping it, namely, international corporate capitalism, experiential and therapeutic religion, transnational religious networks, the megachurch phenomenon, consumerist culture, and fast-moving technological changes in communications.

Just where all this might go was highlighted in a recent article in the New York Times, “Facebook Wants to Host Your Virtual Pew.”39 The reporter, Elizabeth Dias, writes that “Months before the megachurch Hillsong opened its new outpost in Atlanta, its pastor sought advice on how to build a church in a pandemic. From Facebook.” Facebook, which has over three billion monthly users, more than the number of worldwide Christian adherents, is allegedly building connections with faith traditions as a way of building its brand and improving its reputation. Sheryl Sandberg, the company’s chief operating officer, is reported as saying that “Faith organizations and social media are a natural fit because fundamentally both are about connection. Our hope is that one day people will host religious services in virtual reality spaces as well, or use augmented reality as an educational tool to teach their children the story of their faith.”40 What these connections between tech giants and global evangelical enterprises show is that each is making bets about the benefits of symbiotic relationships that will deliver market share and worldwide Christian growth, whether through conversions or virtual spirituality. The problem is that it is hard to know whether the beneficiaries will be known as customers, consumers, or congregants, or if it even makes much difference.

Photo by Jay-Pee Peña on Unsplash

Given that we are all living through a period of rapid religious and cultural changes, it is not easy to estimate their long-term salience. Will these changes, which are partly inspired and facilitated by digital media and the internet, ultimately result in a religious revolution as profound as the one ushered in by print and Protestantism exactly five hundred years ago? In a controversial recent book by Joseph Henrich, an evolutionary biologist at Harvard, titled The WEIRDest People in the World (his acronym for Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich and Democratic), he makes a case for the central importance of the Lutheran Reformation in the evolution of the particular cultural and psychological characteristics of Western civilization. Luther himself was the product of three voluntary associations (a monk, in a university, in a charter town), and Henrich makes a compelling case for a causal relationship, not just an association, between Protestantism and increased literacy rates across Germany, Western Europe, and the wider world. Moreover, “broad-based literacy changed people’s brains and altered their cognitive abilities in domains related to memory, visual processing, facial recognition, numerical exactness, and problem-solving.”41 He suggests that changes in family structure produced by medieval Christianity and the cultural processes unlocked by the Reformation—especially increased literacy and information distribution—helped produce the WEIRD changes in Western culture. His main argument is that one cannot separate culture from psychology or psychology from biology, because culture physically rewires our brains and thereby shapes how we think, which in turn reshapes culture.

It is good to be clear that Henrich is not contending for some kind of innate racial categories and characteristics that somehow explain the rise of Western civilization, thereby endorsing its alleged superiority or rapaciousness; rather, he presents compelling data to show that culture rewires our brains and the Lutheran Reformation was a major contributor, not just to religious change, but to cultural change capaciously understood.

If there is merit to that argument, what then might be said in a hundred years’ time about the synergistic relationship between the digital revolution and religious and cultural change? I offer six possibilities for future discussion. The first is that the sheer speed, lack of regulation, and increased personal access of social media will accelerate the changes in Western Christianity that were already evident in the profound cultural shifts of the 1960s and 1970s. Second, there will be a continued weakening of traditional denominational Christianity, both from within and without. Within those denominations, social media professionals will increase their influence and theologians will have a diminished role. Institutions training future priests, pastors, and ministers, if they survive at all, will have to acknowledge that reality or risk going under. Third, Christianity will be impacted by both greater indigenization in the religious cultures of the global South and increasing homogenization produced by transnational networks and other manifestations of globalization. It is possible that the tension between indigenized particularity and globalized homogeneity will be one of the most hotly debated topics of twenty-first-century Christianity. Fourth, individuals, especially those equipped to use social media, will continue to construct and find meaning in spiritualities designed by themselves or by networked cohorts with whom they choose to affiliate. Fifth, the social functions served by religion—quests for meaning and values, community connections and rituals, and spirituality and transcendence—will continue to be important and will inevitably produce continuity and change. If Joseph Henrich were to write a sequel in a hundred years’ time about the relationship between religious, cultural, and psychological change in the early twenty-first century, my guess is that he could do worse than take courses in Nigerian Pentecostalism and the ethnomusicology of Hillsong. Alas for us, it is very unlikely that the significant action will have taken place at either Harvard or Edinburgh.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, in the words of the Watergate investigation, is to “follow the money.” To go back to McLeod’s delineation of Christian history into the three categories of the register, the ticket, and the website, these three epochs also have different financial models. The registering churches of medieval and early modern Christendom were largely financed by state-enforced ecclesiastical taxation in the form of tithes, church rates, and other financial exactions from populations who had to pay for religious establishments, whether they used them or not. The rise of British Nonconformity, Methodism, and American nonestablishment congregationalism, of all stripes, heralded not only new forms of religion, but also new financial models based on voluntary giving and donations, big and small. But the worldwide religious organizations of the postmodern era are financed on a different model. They expand their enterprises by product development, branding, marketing, and merchandizing. Where there is money, there is also opportunity and growth. But there is also corruption and capitulation to the demands of the market.

The financing of religion has always been controversial and also deeply revealing about the location of power within religious traditions.

The financing of religion has always been controversial and also deeply revealing about the location of power within religious traditions. In the Old Christendom model, established churches found themselves indissolubly linked to early modern political establishments on which they depended for their financial survival. When those political establishments were themselves challenged by new social forces, established churches found themselves representing interests perceived to be antithetical to those of their own parishioners. Throughout Western Europe, established churches paid a heavy price for their social and political loyalties in the age of revolutions from which they never recovered. Similarly, within new religious movements, like the Methodists, the original ideal of shared resources and egalitarian voluntary subscriptions eventually gave way to disproportionate influence exercised by the largest donors and the social forces they represented.42 It is at least possible that the funding models of the INC and megachurches discussed in this lecture, based as they are on products, marketing, and merchandising, on the one hand, and on various forms of prosperity theology, on the other, will raise expectations that cannot be delivered and keep producing leaders with little regulation of their prudence or probity.

The Lutheran Reformation progressed on the heels of an increasingly capitalistic printing industry, and over time produced increased literacy and the accumulation of cultural by-products of mass literacy. Five hundred years later, the digital revolution will transform the nature of global Christianity, from its funding models to its worship experiences, and from its community rituals to its information distribution. Big changes are on their way. What will be the balance sheet?

Here are two provisional perspectives. The first comes from the reflection of some theologians in the Zoom era, who are compelled to rethink church not as an institution with buildings and hierarchical orders but as one of egalitarian and almost invisible communities connected by a desire for community even when bodies are not physically present. A second comes from the Empathy Diaries by Sherry Turkle, the founding director of the MIT Initiative on Technology and Self. Her vision of the digital era is much more dystopian. “When we are online,” she writes, “and when we are tracked by our devices our lives are bought and sold in bits and pieces to the highest bidder and for any purpose. . . . The social-media business model evolved to sell our privacy in ways that fracture both our intimacy and our democracy.”43 One might add that it has the capacity to fracture our empathy and our spirituality. Time will tell.

Notes:

- Niall Ferguson, The Square and the Tower: Networks and Power, from the Freemasons to Facebook (Penguin Press, 2018), 400.

- See especially Hugh McLeod, The Religious Crisis of the 1960s (Oxford University Press, 2007).

- Hugh McLeod, “Western Religion in the Long 1960s,” Journal of Ecclesiastical History 70, no. 4 (2019): 823–31.

- See Callum G. Brown, The Death of Christian Britain: Understanding Secularisation, 1800–2000 (Routledge, 2001); The Decline of Christendom in Western Europe, 1750–2000, ed. Hugh McLeod and Werner Ustorf (Cambridge University Press, 2003); Secularisation in the Christian World: Essays in Honour of Hugh McLeod, ed. Callum G. Brown and Michael Snape (Ashgate, 2010); Robert D. Putnam and David E. Campbell, American Grace: How Religion Divides and Unites Us (Simon & Schuster, 2010); Clive D. Field, Secularization in the Long 1960s: Numerating Religion in Britain (Oxford University Press, 2017); and Sam Brewitt-Taylor, Christian Radicalism in the Church of England and the Invention of the British Sixties, 1957–1970: The Hope of a World Transformed (Oxford University Press, 2018).

- Secularization and Religious Innovation in the North Atlantic World, ed. David Hempton and Hugh McLeod (Oxford University Press, 2017).

- See Heidi Campbell, Exploring Religious Community Online: We Are One in the Network (Peter Lang, 2005); and Heidi A. Campbell and Stephen Garner, Networked Theology: Negotiating Faith in Digital Culture (Baker Academic, 2016).

- Campbell and Garner, Networked Theology, 8–9.

- Campbell, Exploring Religious Community Online, 195.

- Campbell and Garner, Networked Theology, 1–3.

- Heidi A. Campbell, Digital Creatives and the Rethinking of Religious Authority (Routledge, 2021), 1–4.

- See the excellent conclusion in ibid., 193–209.

- See, for example, Wade Clark Roof, Spiritual Marketplace: Baby Boomers and the Remaking of American Religion (Princeton University Press, 1999), which is an insightful interpretation of trends in American religion ca.1990s, before the impact of the digital revolution.

- Daniel Vaca, Evangelicals Incorporated: Books and the Business of Religion in America (Harvard University Press, 2019), 232.

- Christopher W. Boerl and Katie Donbavand, A God More Powerful than Yours: American Evangelicals, Politics, and the Internet Age (Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2015), 110.

- Ruth Graham, “Christian Prophecy Movement Is Hit Hard by Trump’s Defeat,” New York Times, February 12, 2021.

- Angie Thurston and Casper ter Kuile, How We Gather, sacred.design/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/How_We_Gather_Digital_4.11.17.pdf.

- Casper ter Kuile, The Power of Ritual: Turning Everyday Activities into Soulful Practices (HarperOne, 2020).

- Stewart M. Hoover, Religion in the Media Age (Routledge, 2006), 289.

- See Margaret Wertheim, The Pearly Gates of Cyberspace: A History of Space from Dante to the Internet (W. W. Norton, 1999), 256.

- Heidi A. Campbell, When Religion Meets New Media (Routledge, 2010).

- Brad Christerson and Richard Flory, The Rise of Network Christianity: How Independent Leaders Are Changing the Religious Landscape (Oxford University Press, 2017), 45.

- Ibid., 121.

- Ibid., 124.

- Ibid., 165–66.

- A Moving Faith: Mega Churches Go South, ed. Jonathan D. James (Sage, 2015).

- Kate Bowler, Blessed: A History of the American Prosperity Gospel (Oxford University Press, 2013), 229.

- Ibid., 230.

- Ibid., 84–85, 121, 185–86.

- Kip C. Richardson, “Big Religion: The Cultural Origins of the American Megachurch” (PhD diss., Harvard University, 2017). Richardson locates the cultural origins of American megachurches further back into the nineteenth century than is conventionally assumed. He argues that the authorizing discourse is bigness itself, which acts as an inner theological motor driving the various cultural, denominational, and religious expressions.

- Walter C. Ihejirika and Godwin B. Okon, “Mega Churches and Megaphones: Nigerian Church Leaders and Their Media Ministries,” in A Moving Faith (ed. James), 62–82. See also Afe Adogame, The African Christian Diaspora: New Currents and Emerging Trends in World Christianity (Bloomsbury, 2013).

- Ihejirika and Okon, “Mega Churches and Megaphones,” 73–78.

- Adogame, The African Christian Diaspora, 73–74.

- Ibid., 191–211.

- Jeaney Yip, “Marketing the Sacred: The Case of Hillsong Church, Australia,” in A Moving Faith (ed. James), 107.

- Ibid.,” 106–26.

- Tom Wagner, “Music as a Mediated Object, Music as a Medium: Towards a Media Ecological View of Congregational Music,” in Congregational Music-Making and Community in a Mediated Age, ed. Anna E. Nekola and Tom Wagner (Ashgate, 2015), 25–44, at 25, 27.

- Yip, “Marketing the Sacred,” 112.

- David Hempton, Methodism: Empire of the Spirit (Yale University Press, 2005), 68–74. I write that Methodist hymns “supplied a poetic music of the heart for a religion of the heart. The medium and the message were in perfect harmony” (73). For a fine analysis of the role of hymns in American religion, see Stephen Marini, “Hymnody as History: Early Evangelical Hymns and the Recovery of American Popular Religion,” Church History 71 (June 2002): 273–306.

- Elizabeth Dias, “Facebook Wants to Host Your Virtual Pew,” New York Times, July 26, 2021.

- Ibid.

- Joseph Henrich, The WEIRDest People in the World: How the West Became Psychologically Peculiar and Particularly Prosperous (Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 2020), 7–17 and 415–29, at 15.

- David Hempton, “A Tale of Preachers and Beggars: Methodism and Money in the Great Age of Transatlantic Expansion, 1780–1830,” in God and Mammon: Protestants, Money, and the Market, 1790–1860, ed. Mark A. Noll (Oxford University Press, 2001), 123–46. The essays in this book make a powerful case for paying attention to the financing of religious enterprises and the cultural contexts in which they are embedded. See also David Hempton, “Organizing Concepts and ‘Small Differences’ in the Comparative Secularization of Western Europe and the United States,” in Secularization and Religious Innovation (ed. Hempton and McLeod), 351–73.

- Sherry Turkle, The Empathy Diaries: A Memoir (Penguin Press, 2021), 337.

David N. Hempton is Dean of the Faculty of Divinity, Alonzo L. McDonald Family Professor of Evangelical Theological Studies, and John Lord O’Brian Professor of Divinity.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.