Dialogue

On Chanting and Consciousness

Illustration by Andrew Zbihlyj

By Diane Mehta

My grandmother always did the chanting. A vague mystery hung in the perpetual heat while my extended family stood there, facing a photograph of the emaciated Jain prodigy and scholar Srimad Rajchandra, and listened to our grandmother’s voice. Her scratchy alto had a rugged undertone, with the hint of a chuckle in the higher register. Ba, as she was called, delivered the verses in a methodical manner. Her phrasing paralleled the familiar sounds of other kinds of ritualized chanting: a muezzin’s call, a cantor singing, choral music, church bells, sirens, mothers yelling out the window to their children and calling them home.

Ba’s face was round as a tin of gingerbread cookies, and she never wore makeup. She parted her hair in the middle, smoothed it back tight, and twisted it efficiently into a bun. I loved watching her dress, half-outfitted in a tumble of soft white cotton petticoats and tops as she sat on her bed, combing her long mane of oiled black locks, smelling of powder and starch. Her handsome face is replicated in the polished movie-star facial structures of her children.

Jainism defined Ba’s presence in the slow, sturdy way she walked, her devotion to the rigors of prayer and chanting, and the self-imposed restrictions on her life, such as days of fasting in which she took nothing but boiled water. The purpose of the fast is to control your mind instead of letting your mind control you, explains my aunt, who has increasingly tried to live a life equally devout, even if as a statistician she is more scientific than her mother. The logic works like this: Fasting lets you get rid of some old karma and collect good karma, and it trains the soul to salvation because the soul is after everlasting salvation. Food is one of many worldly pleasures. “The quality of the soul is to know things,” my aunt says. So the ritual is a kind of training for the soul in search of infinite knowledge—achieved by renunciation. Chanting helps you get through it. It’s an admirable way to think about things, though my Jewish-Jain idea of the soul is not their idea of the soul. My imagined soul is one that’s full of feeling, not free of feeling.

Jains don’t believe in God—neither the Judeo-Christian kind nor the ancient Hindu pantheon—but they revere these saints for achieving nirvana, at which point they are godlike. What Jainism shares with Hinduism (the majority religion in India) is the idea that if you collect good karma, you are reborn into a better being and eventually can achieve nirvana. In Hinduism, this social climbing is inextricably tied to the caste system: an insect is reborn as a dog, a low caste person moves into a higher caste, a woman in her next life becomes a man. But because Jainism has no caste system, it is through acts of karma and renunciation alone that a person attains nirvana, breaks the bondage of the life cycle, and becomes a saint. In Jain cosmology, 24 men have reached this stage. They are known as tirthankaras, the most recent being Mahavira, a contemporary of the Buddha (ca. 500 BCE).1

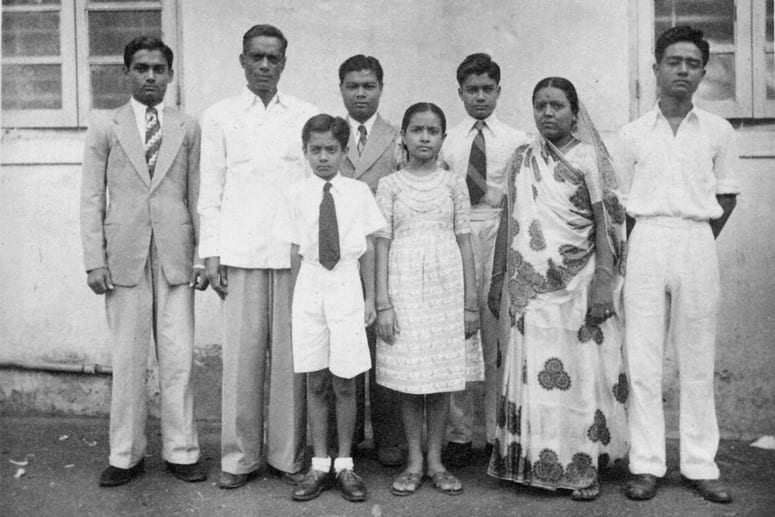

The author’s grandparents and their six children in 1952 in Rajkot, a city in the state of Gujarat in North India. Courtesy Diane Mehta

My grandmother didn’t pay much interest to religion until her oldest son, Chandrakant, died in 1959. She never got over Chandrakant’s death. After he died, Ba turned increasingly devout and began reading about religion, morality, and ethics. According to my father, Ba’s mother had always been devout and had led prayer groups in Bombay. As a child, he and his siblings listened to several prayer songs daily, but there was no tradition of chanting back then. Ba and his grandmother used a mala, similar to a rosary but with 108 beads, during the prayers. My father, like many Jain children, learned the navkar mantra, the most basic Jain chant that children learn when they are young. It comprises nine two-word prayers paying respect to others who have reached higher stages of spirituality than you.

When I asked my father about the navkar mantra, I was shocked to find that, even in his late 80s, he mutters it to himself before bed, not out of religiosity but out of habit. He’d done it for years, along with counting numbers and square numbers and other “difficult and repetitive and boring things,” as a way of getting to sleep.

The habits that punctuate our daily existence add structure and stability to our lives in part because habits are ostensibly devoid of emotion. Your arm reaches out in the way to which it is accustomed and wedges a spatula under two eggs, which it balances briefly before the precarious flip. Salt is dispersed. A fork is retrieved from the drawer that will slide in and out however long you live for, and unthinkingly you eat. We rely on the rituals that make us feel safe. But beneath each thing is something extraordinary: an egg is a semipermeable membrane composed of calcium carbonate crystals and a 40-protein albumen miracle surrounded by opaque chalazae ropes clinging to the glorious orange-yellow yolk, all warmly hatched from a two-legged feathered hen. How deliriously inside out moments can be, if we realize what bubbles underneath them.

If you care about something, you make time for it. Besides her children, Ba’s prayers were her life’s work. Maybe chanting gave Ba some remove from the travails or social interactions that so define modern life, or perhaps it genuinely offered calm, like meditation with music. She was so deeply entrenched in living a Jain life. But if it all started as a gesture of grief for Chandrakant, did she believe that somewhere in her prayers, and in her voice, her son was still alive? Was chanting a foil against feeling, or did chanting’s limitations liberate feeling—in the way that a classical sonnet liberates and structures the chaos of feeling in the macramé of its tightly woven rhymes? We have infinite bonds with our children and our childhood.

My father’s recitation of the navkar mantra in recent years calmed his mind, and maybe it made him a little sleepy. He led a secular life and had a secular Jewish wife. He recited these mantras as a child and again as an old man. How could this practice not evoke memories of a past life? He lights up at the chance to talk about his childhood, so maybe, for those five minutes of chanting, he slips into the comfort of being a child again, praying with his mother at night. I believe there is some childhood in him. I still occasionally sing the Hebrew round Im tirtzu ein zo agada (“If you will it, it is not a dream”) to my son, who is now 17, when he is pensive. I learned it in synagogue when we moved from Bombay to New Jersey and I have held it dear since. I have sung it to my son his whole life as I put him to sleep. He learned to sing the Hebrew words with me. Maybe when he is old, he will mutter it to himself, before going to sleep, and he will remember me.

Secular Jainism was such an accommodating religion in my family that I still don’t understand my relationship to it. If I want to practice, I am Jain. If I do not practice, I am not Jain. My most devoted relatives work Jain prayer into their lives the way Americans build churchgoing, yoga, or fly fishing into their lives—though this in some mainstream way seems to be true for most moderate Hindus, Parsis, and Muslims in India, too. Religion is a hat of feathers, but it is not a costume; it does not define you. For Jains who yearn to be devout, it is a strict path to achieving moksha (freedom from rebirth: nirvana), but for others, it accommodates your willingness to engage or not. You can be Jain, like my father, in spirit if not in practice. There is no on or off button, no conversion ceremony, no study requirement. It is humanled, a matter of devotion, like needlework or parenting or an apprenticeship for brick masonry.

The variety of Jainism I was taught involves trying to be a good person and to avoid doing harm.2 You do what you can. Our biases and desires lead us to different versions of what harm is. But chanting somehow seems to remove all these concerns as you do it. Time feels suspended, words hang on the air, and the pace of life slows to the rhythm of prayer. I think of time as a rowboat in our universe, and chanting is the sound that oars make. But I do not see why the oars are not, say, a spider’s web, a sound wave, or pi, the geometry of the world.

My aunt points out that chanting is easy. It can be done on the fly, and you don’t need to be physically or even mentally fit to do it. You don’t need money. Five minutes is fine. Chanting is not an end in itself. This kind of devotion is harder for me to understand than the secular devotions of the body, like sex or love, or the devotions of the mind, like reading or writing or the bloom of imagination, and dreams of stairways and tunnels. Chanting forces a pause in the routine, and the recitation of words occupies your mind as they absorb the time. Is that what training the mind is? I know what training the mind to love is, but that’s closer to learning to feel, while chanting resembles the opposite, the practice of putting feelings aside, an enviable compartmentalizing.

One of the main tenets of Jainism is ahimsa, or nonviolence, to avoid destroying life or harming others, but I am suspicious that the renunciations of Jainism are effective as a way of staving off the violence of feeling. For my grandmother and her children, Jainism offered a way to keep emotions in check. You can fast to exhaustion, chant to focus the mind and calm the breath, and repeat the phrases that meditate you into believing that everything will be fine. None of this will preempt emotion; you try, my aunt explained once, not to be angry, but you may still be angry. There is also a detachment from care that you pay for in your relationships with others, as if you can unbutton your problems like a shirt that can be put in the laundry.

Chanting is a gesture of my childhood, and it is a kind of comfort, despite the fact that I do not do it. There is a deep, pained yearning embedded in it that has something to do with Ba and her starched cotton petticoat smell and my mother’s Jewish songs.

Chanting is a gesture of my childhood, and it is a kind of comfort, despite the fact that I do not do it. There is a deep, pained yearning embedded in it that has something to do with Ba and her starched cotton petticoat smell and my mother’s Jewish songs I learned at her New Jersey synagogue and Poconos summer camp, sitting in the amphitheater that slants down to a glassy forest-rimmed lake and a striking, voluptuous woman with chestnut Rapunzel hair strumming acoustic guitar on a wooden stage. Chanting has something painful to do with Lamaze and the breath, during the ravaging if ordinary labor of my son’s delivery. It is similarly in tune with the rhythm of song that evokes that hard-won feeling you dissolve into after, say, 20 hours of laboring over a poem or 40 hours of fiction and then the moment briefly hits you, and you’re in that breathless groove of confident exactitude and suddenly there are garlic and sapphires in the mud and four seasons in you.

When I lived by the sea in San Francisco, I commuted to T. S. Eliot’s sing-song recitation of his masterpiece, The Four Quartets, which got stuck in my barebones Toyota Tercel’s cassette player for three months. Eliot’s meditation on time, written over six years, is loosely structured around the four classical elements (air, earth, water, fire) that reflect the four seasons. When the junky cassette player broke and started playing, on repeat, a poem about time, it started as a funny refrain but then became annoying. Aggrieved, I considered my options: suffer in silence or listen to Eliot over and over. I chose Eliot.

Those 30 minutes I commuted each way evolved into a time I lovingly anticipated as I raced along San Francisco’s Great Highway. Ocean Beach was populated by surfers and fishermen, and then I would merge with Skyline Boulevard by Fort Funston where hang gliders hovered above the cliffs, and ease onto Route 1 along the coast, through fast-moving curtains of fog at 35 miles per hour, the safest speed to continue forward while the reliable winds swept the fog aside. As I drove south of San Francisco, the fog receded or swirled back out to sea and the skies opened up as I cut east and upshifted onto sunshiny Interstate 280, the road of all people, not my half-secret coastal detour.

Through fog and big blue skies, Eliot still chanted for me. “Garlic and sapphires in the mud,” we’d intone together, dropping our voices an octave at the mimetic mud, and I’d smile at the piquant regularity of this phrase that dug into some guttural place in me, physically and verbally, before releasing me from its depths and into the long pause that lifted into soprano moments. I listened 60 minutes a day to the Four Quartets’ incantatory rhythm.

Words move, music moves

Only in time; but that which is only living

Can only die. Words, after speech, reach

Into the silence. Only by the form, the pattern,

Can words or music reach

The stillness, as a Chinese jar still

Moves perpetually in its stillness.

That passage from “Burnt Norton” says that time is fluid, but you can move through it in ways that are meaningful if not permanent. During those months of driving, Eliot’s chanting became my chanting. Perhaps my recitation was empty of spiritual meaning, but his playful, plaintive rhythms imparted joy to no end.

The American Eliot himself was disillusioned, his life marked by nervous breakdowns and domestic anxiety; his conversion to Anglicanism while taking British citizenship grounded him—though the philosophy of the Quartets is a mixed bag spiritually, with a wide-eyed nod to the Bhagavad Gita (“Song of God”) in India’s Sanskrit Hindu epic, the Mahabharata. The Gita is a dialogue between Prince Arjuna and Krishna, avatar of Lord Vishnu, creator of the universe, on the battlefield. Arjuna hesitates at the prospect of killing his relatives in this war between two branches of his family, but Krishna, disguised as his charioteer, persuades him to fight out of duty. It’s the fruit of Arjuna’s action that’s at stake: The soul requires action to attain enlightenment. Mahatma Gandhi, the architect of the nonviolent resistance movement that won India her freedom in 1947, said the Gita was a metaphor for the inner struggle.

But how do you tend the soul?

The Quartets offer no resolution but are a literal path through a rose garden and a spiritual path much like the one that Ba was on and which my aunt is also on. They are a pursuit of a higher experience—but what is the nature of that experience? The neurologist Robert A. Burton, who studied consciousness, says there are neural correlates for emotional responses, but it’s not clear what sensations and responses define experience: “I know the brain creates a sense of self, but that tells me little about the nature of the sensation of ‘I-ness.’ If the self is a brain-generated construct, I’m still left wondering who or what is experiencing the illusion of being me.” Reluctantly, he says, it dawned on him that the pursuit of the nature of consciousness “is driven by the same urges that made us dream up gods and demons, souls and afterlife.”3

It is difficult to imagine we will ever know what consciousness is, given that the only tools we have to decipher it are our own brains, and that feels like a chicken and egg situation. Burton has tapped into better questions: Why must we know? “Theories of consciousness are how we wish to see ourselves in the world, and how we wish the world might be,” Burton says, the implication being that we will never know.

The author’s grandparents and five of their six children in 1973 on the day before they moved to the United States. Her father is in the first row on the left. Courtesy Diane Mehta

So I wonder, when it comes to Ba, or my aunt, or any religious Jain seeking higher experience, what do we transcend, and where to? I do not understand Ba’s spiritual feelings, but I do understand the way she cooked for us or laughed, or put her dentures in a cup that fizzled and fascinated us, or brushed her inky black and white hair. Ba’s devotion, to me, seems hard on the intellect in the way of all religions. You question your faith, you demand answers. But I wonder if the ability to achieve effortlessness in prayer is any different from other rituals of faith. There is no philosophy that will imbue you with the feeling you seek; it is you who have to dig up that feeling. I am more than a little enamored of Eliot’s idea that words, after speech, reach into the silence. Going to temple isn’t going to buy you enlightenment, but will prayer and chanting help get you there?

Thirty years ago, I asked Ba if she’d change anything in her life, and she replied that she’d have liked to have gone to more parties and bought more jewelry. She grinned and her dentures sparkled. I didn’t know how to respond. Ba’s reply, I realize now, was entirely ironic. She had no interest in those things. But she did respect the life choices of others and she understood the desire for fun. One night while visiting Bombay in my 20s, I had a standoff with an aunt because I wanted to go to a party with some Indian guys from London I’d met on the plane. We argued insufferably. Ba cut in. The room grew quiet. “Ba says go, have fun,” translated my cousin. I grinned at Ba and went to my party, where I had a miserable time trying to look pretty.

My aunt says she also has not achieved the effortlessness described in Rajchandra’s prayer sahajätma swarup paramguru, even with more than half a lifetime of study, various renunciations, and plenty of chanting. For years, she has returned to India to study with three Jain female sadhus in the town of Khambhat in Gujarat state.4 She met them, with Ba, when they delivered a sermon in 1987. She stays with them during her visit, to see how they live and to learn from them. Because they are Jain monks, they have no possessions and are entirely supported by the community, which invites them into their homes for meals and pays for their medical needs. Their job is to preach to society. The most senior woman gives a pravachan, a sermon on scripture, in the morning and afternoon. In the evenings, the teaching is informal; they give my aunt notes or books to read and they discuss them, and they talk for hours. She has gone to remarkable lengths to advance in her journey, motivated by her gurus, and to become a more nuanced practitioner of Jainism.

But that feeling of effortlessness has eluded her. The concept eludes me. Does it feel like concentration, or like flying feels for winged creatures? If it is akin to muscle memory, I suspect it is weighed more heavily to the memory part, because the brain is stronger than the body. There are so many ways in which you want life to be effortless, and reciting a chant seems easier than all of them.

My only reference for understanding this sense of contentment or effortlessness is a physical one: desire. In India, arranged marriages sometimes blossom unexpectedly into love—in many cases, from habit. It’s a kind of proof: we love what we are familiar with more than we despise it—love is effortless when it is cumulative. Human events punctuate time passing, which convinces me that Burton is right: it is our tireless quest for answers about the nature of consciousness that motivates us.

The atheist philosopher Daniel Dennett says that consciousness is an illusion, a cheap trick. The brain has its mechanics to which we attach the idea of consciousness. We write our Everygod books and endow those humans with superpower status. We set up rules for followers, who fund our churches, temples, synagogues, and retreats. That doesn’t mean there’s no higher purpose or that we cannot transcend ourselves, only that we mark what is religious in human ways, because we are schooled in the ways of people who say that God speaks through them, but we are not schooled in the ways of God itself.

I believe this, but I also believe that Ba and my aunt are onto something I will never understand. I prefer to be attentive to experience, instead of figuring out what experience isn’t. When I’m in India, a Muslim call to prayer creates a tiny rush of adrenaline and then a calm in me. It is a marker of people putting aside their worries or chores or work and turning away from themselves. In a temple, or when listening to relatives pray, I drift. I watch the person’s lips, follow the vowels as they move across the stone floor, and feel time passing. Sounds become beautiful, like Ba’s alto voice.

I look out the window repeatedly while at my desk and observe that trees are moving. I watch them for a while, and remember Virginia Woolf describing wild-moving clouds in her brief, brilliant book On Illness. If she had not been ill, would she have noticed the clouds? We have not slowed down enough. While time passes, isn’t it lovely to discover your own repetitions for it? If my dad’s habit of reciting the navkar mantra lasted all of his life, isn’t his atheism an act of devotion?

I do not need to believe in God to practice the work of the soul. When I was younger, I’d listen to a song hundreds of times to ride its rhythm in the poem I was writing. The lyrics and music took my choices away and let my mind latch onto the sound I wanted, which I twisted into language. Within the poem, anything could happen. Is this similar to those months with Eliot stuck in my cassette player, and similar to chanting? You become immersed in a place where, guided by words, you are free of attachments—and then? Chanting leaves no space for your mind to wander, because it is repetitive.

No, says my aunt when I ask her now. In the first stage of chanting you are still involved in worldly things. In the second stage, you push those away. In the third, you begin to ask questions: “Why am I saying Ram, Ram, instead of Diane, Diane? You think of what Ram did.” Most people end here, in the middle. “It is the beginning of the next stage that you think about your guru. What is good for my soul? Is there a soul?” The serious work of the soul is when chanting becomes intellectual. It’s like the first time you read a poem and you have one set of feelings. Later you get a more elaborate meaning.

For example, my aunt usually avoids eating root vegetables because if you pull up the root of a plant, you destroy its life. My aunt learned from those Jain sadhus that there were 35 vegetables to avoid, and not only roots. She had not heard of 27 of them. But the question about what is good for your soul is a fluid one. A potato will die if you pull it out of the soil, my aunt explains, but you can replant it or put it in water, and it will grow another tuber. On the other hand, argues my cousin, her daughter, you are taking the source of its life to feed yourself, even if it grows another tuber.

When Ba chanted, in her house in Sion, a suburb of Bombay, we stood around her while her voice ambled a cappella over the syllables with which we’d grown familiar. She faced a photograph of Rajchandra, devout and emaciated, cross-legged in a loincloth. He lived inside her white cupboard and came alive with incense and our gaze. I wonder if she was reciting this prayer, from his letters:

He prabhu he prabhu shu kahu, dina nath dayal

Hu to dosh anant nu bhajan chu karulal

Oh Lord, what can I tell you, you are very kind to everyone and I am full of mistakes.

My father says that as children they heard that prayer nightly. For me, one prayer is as good as another because I’m not looking for meaning. But when Ba chanted, in Gujarati, time felt suspended. Am I also full of mistakes? Chanting is free. You only need five minutes. Why don’t I do it? Why only with Eliot?

I have no attachment to Jainism, and no attachment to Ba’s prayers. But mumbling along to them, decades ago, gave me a chance to feel Jainism in what is arguably its truest form: practiced by those in the middle of prayer, always in the middle of practicing faith, in the middle of a halfway house for the soul.

There’s something about music and repetition that makes me feel privy to some sort of collective experience. If the nature of that experience is hotly contested by philosophers, it doesn’t matter to me. My soul is troubled. I am full of mistakes. My soul will never be free of desire, because desire is the only place where suffering does not exist for me.

I suspect I have misunderstood the teaching entirely.

Notes:

- Jains believe there were many more Jain saints before Mahavira. (Not all saints are tirthankaras. Some may be on their way to becoming a tirthankara, but are not there yet.) People assume Jains don’t believe in God. This is true if you assume that God is the creator of the world. Jains don’t believe in a creator. They believe that although there is no creator, the “pure soul” is God—or godlike. For convenience, modern Jainism dates the start of the religion to Mahavira’s lifetime and teachings in the sixth century BCE.

- My takeaway from growing up in a Jain family was that being a Jain hinges on nonviolence. The concept is not only material. It does mean one must avoid harming all forms of life, from people to insects to root vegetables. But at its core is the even more meaningful goal of avoiding doing harm to other people through your actions or thoughts. Mahatma Gandhi famously adapted Jainism’s tenet of nonviolence and used it as an organizing principle for a decades-long civil disobedience movement to purge the British Raj from India.

- Robert A. Burton, “When Neurology Becomes Theology: A Neurologist’s Perspective on Research into Consciousness,” Nautilus Magazine, no. 49, June 15, 2017.

- A small number of Jains are ascetics, or monks, or sadhus; they are supported by the Jain community, and some preach or are itinerant. Lay Jains practice with varying degrees of commitment.

Diane Mehta is the author of the poetry collection Forest with Castanets (Four Way Books, 2019). Her poems have appeared in The New Yorker and The American Poetry Review. Recent essays are in Agni and the Southern Humanity Review. She received a 2020 Spring Literature Grant from the Café Royale Cultural Foundation for her nonfiction writing.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.