Dialogue

Nuns and Nones Meet on the Edge

The pull that some Nones feel toward contemplative, social action has led to an unlikely collaboration with nuns, described as an “apprenticeship in prophetic community.”

Photo courtesy Katie Gordon

[T]he point is, to live everything. Live the questions now. Perhaps you will then gradually, without noticing it, live along some distant day into the answer.

—Rainer Maria Rilke, Letters to a Young Poet

AFTER I GRADUATED from Harvard Divinity School in May 2019, I moved into a monastery. As someone who entered divinity school as a non-religious seeker, a monastery might seem like the last place I’d inhabit. But it was the first place I wanted to go.

During the past few years of work and study, I have seen—and experienced, firsthand—the desire that many millennials have for contemplative practice and monasticism. At the same time, I have learned about the timelessness of this desire and hunger. Each age expresses this hunger in new yet timeless ways, with a spirit of both renewal and remembering. In my own millennial generation, marked by global crises, distrust of institutions, fluidity of place and identity, this hunger is being expressed in fresh ways. But the contemplative and monastic traditions also transcend the particular context of this time and my generation.

Krista Tippett, in her 2016 book, Becoming Wise: An Inquiry into the Mystery and Art of Living, wrote that “The Nones of this age are ecumenical, humanist, transreligious. But in their midst are analogs to the original monastics: spiritual rebels and seekers on the margins of established religion, pointing tradition back to its own untamable, countercultural, service-oriented heart.”1 (Nones are people who don’t affiliate with any religious tradition and are a rising segment of the U.S. population.)

Throughout my time in divinity school, this is a parallel that I have carried with me. As I read about the early desert fathers and mothers, Saint Benedict, and contemplatives over the millennia, I found it impossible not to draw parallels to our own time. The monastics were ordinary people who saw society in its brokenness, corruption, and oppression and sought to live in a different way. Early monastics left the empire of the city for a more peaceful life in the desert. Monasteries became centers and sanctuaries where social, cultural, and spiritual life could continue, even in the midst of collapse. Contemplative traditions over the ages have created and sustained practices that allow for a spirituality that grounds people in something deeper than what meets the eye.

In the midst of institutionalized and systemized corruption and oppression, it is no wonder that increasing numbers of people are leaving organizational affiliations in order to seek another way. Given the current political and ecological crises, perhaps these modern-day monastics can call us into another way of being in the world.

There are many ways this monastic urge is being lived today by groups who might be considered religious rebels, spiritual misfits, or Nones. The New Monasticism Movement has coalesced in diverse forms yet is marked by grassroots ecumenism and prophetic witness. Shane Claiborne’s The Simple Way in Philadelphia models an intentional community in the inner city—showing monastic engagement rather than withdrawal from the world. In New York, there is the Brooklyn Center for Sacred Activism, meant to bridge the divide that too often exists between spirituality and social transformation. On the West Coast, there is a new intergenerational religious order that is rooted in the reality of our current ecological crisis, called Order of the Sacred Earth, founded in part by creation theologian Matthew Fox. Finally, there are opportunities emerging for individuals as well, like internships at monasteries—such as one at the Isle of Wight monastery in the UK, recently documented in a BBC story2—which give young people a contemplative spiritual formation experience that is not possible in most educational or professional settings today.

When we look at the way that many in emerging generations are moving through the world—spiritually, vocationally, and across traditions—we see that many of these spiritually diverse and socially active young people are not only interested in new ways of doing but also in alternative ways of being in the world. And embracing an alternative way of being directly leads to a more grounded, contemplative, active way of doing.

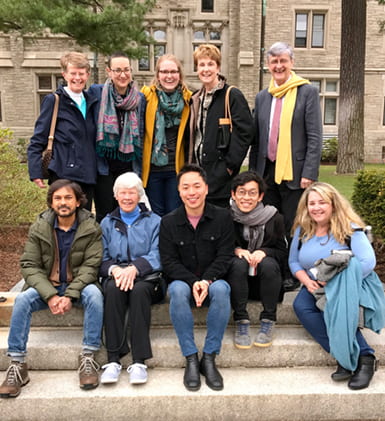

A Nuns and Nones gathering at Harvard Divinity School, April 2019. Photo courtesy Katie Gordon.

The Rule of Benedict, which has guided monastic life for more than 1,500 years, states to monks: “Your way of acting should be different from the world’s way.” Monastic life, according to the Rule, is about creating another way of being in relationship with self, community, and spirit. Writing about contemporary society, Thomas Moore suggests that we live in “an age of anxiety, not a psychological problem but an existential condition created by the busy, productive, and unthoughtful style of modern work, play, and home life.” With this rushed lifestyle, modern life “is not in accord with the fundamental needs of the human heart.” Turning to the Rule, “this ancient sketch of an alternative life,” holds the possibility to “transform a culture of anxiety into a community of peace and mutual regard.”3

In a time when many of us see the dominant narratives and policies to be dictating division, destruction, and dehumanization, perhaps the pull toward the monastic as the alternative is one answer. As people become increasingly frustrated with and disaffiliated from current political and economic structures and systems, monastic traditions offer practices and values that transcend generations and go beyond borders, embodying a way of being and moving in the world that is truly “radical”—radical in the sense of returning to one’s roots.

This pull that many so-called Nones feel toward contemplative, social action has led many of us to find unlikely allies . . . in nuns. So emerged our collaboration: Nuns & Nones. As an alliance between spiritually diverse millennials, women religious (also known as Catholic sisters or nuns), and key partners, we work to create a more just, equitable, and loving world. Together, we are envisioning and creating new futures for the legacies and sacred spaces of religious and monastic life, in response to the social and environmental needs of our times.

Our two distinct groups are rooted in shared desires to live, and act, differently than the world expects—but, in the process, we seek to be able to respond to what the world indeed asks of us. We have found much alignment and mutual encouragement when our two groups come together. By bridging our communities and crossing the boundaries that normally exist between us, the possibilities of what we can do collectively are multiplying.

Those of us who have found one another in this work come from a variety of backgrounds. From interfaith organizing and spiritual community building, to arts and culture work, to solidarity economy organizing, the so-called Nones among us found our way to convents and monasteries as places for conversation and growth, for becoming and belonging. In women religious, we quickly found friends, allies, and mentors in our work for more beautiful and just communities. We found models of organizing that are cooperative and collective. We found charisms, the unique work a community is called to do, which speak to something deeper than social issues alone. We found sacred spaces that have historically welcomed—and continue to welcome—the pilgrim, the seeker, and the refugee for rest and renewal. In each order and congregation, we found people acting as communities rather than as individuals, listening to the signs of the times and responding to the needs around them.

Our collaboration of spiritually diverse millennials and women religious has involved creating spaces, in cities and online, that allow us to learn alongside one another, to inspire and incite our groups into action. Our collective work is continuously emerging and varies from group to group. Some gatherings are ongoing, covenantal-style communities, like Sisters & Seekers in Grand Rapids, Michigan. Other gatherings are intensive residency-style co-living experiments, like a six-month residency that took place at Mercy Center in Burlingame, California.

After experiencing the possibilities these spaces offer, many participants leave with the same reflection, summed up in Sister Janet’s words as “Surprise! We’re soulmates.” Nuns & Nones provides a space of discernment, grounding, and spiritual sustenance and is an attempt to channel wisdom across generations in order to deepen and expand our presence and action in the world. As one organizer states, Nuns & Nones is “an apprenticeship in prophetic community.”

Nuns and Nones participants in front of Andover Hall, April 2019. Photo courtesy Katie Gordon.

As newly discovered, “surprising soulmates,” there is much we hope to do together in community: responding to the climate crisis, serving at the border and ministering to our neighbors, fostering alternatives to systems of extraction and oppression. In learning the histories and stories of women religious, we also learn the histories and stories of social movements—important knowledge as we discern how best to respond to the challenges facing us today. Together, we are finding we might help write a new story.

Emergence theologian Phyllis Tickle wrote in 2013 that we live in “the age of the spirit,” where we are becoming more attuned to the movement of spirit in religious and secular spaces alike.4 I see this movement of spirit in Nuns & Nones. Sisters, especially since Vatican II in the 1960s, when a large-scale renewal in the Catholic Church swept through women religious communities and brought them back to their roots, have been speaking the language of the holy spirit. On what is often perceived as “the other end of the spectrum,” we have seen the trend of individuals increasingly identifying as “spiritual but not religious,” people who refuse institutions but seek personal relationships with the divine. It seems that the spirit is indeed having a moment. For those of us who sense the spirit leading us in these times, as the sisters point out, our job is to slow down, to listen deeply, and to discern how we are being called.

Joan Chittister, an Erie Benedictine nun and prolific writer, speaks of this “crossover moment in history.” In her On Being interview with Krista Tippett in 2007, she said that, in this moment, when both religious life and spiritual life seem to be shifting, we are only simply seeding the question. So many new questions have risen, but “the new answers have not yet emerged. They’re only beginning to simmer in this stew that is humanity.” Experiments like Nuns & Nones, and the many diverse monastic expressions today, are simmering in these questions, in this stew that is humanity.

Too often, the narrative around Nones—and Nuns, for that matter—is one of diminishment and loss. Perhaps not surprisingly, religious institutions worry about what is being left behind or forgotten. But, again drawing from Chittister’s interview with Tippett, to talk about religious life, and for that matter spiritual life, with regard to numbers alone, is a capitalist question to Christian life. It simply misses the point. Instead, we must ask what this trend in disaffiliation or spiritual fluidity reveals about spiritual life in the twenty-first century. If people are leaving something behind, what are they finding? What hope and possibility might this represent?

What I have experienced is that many who get clumped under the umbrella of Nones are tearing down the walls of exclusion that too often exist in religious (and political) institutions, opting for fluidity, movement, and inclusion that is actually a fuller realization of the religious and spiritual visions of many traditions. I see people who are unwilling to compromise their values, who are seeking to live authentically and integrally, and who are challenging those around them to think more critically about faith and values.

Rather than focusing on what is lost, we must look for what is gained. Rather than framing these shifts as a decline, we must look for what is expanding. Rather than telling narratives of isolation, we must seek stories of gathering.

Within our traditions, so many people exist at what Richard Rohr called the edge of the inside: they are still solidly within a tradition or institution, yet they are not part of the hierarchy and are open to movements on the ground. At the same time, the Nones occupy a space that I would call being on the edge of the outside, in which they have left a tradition or institution solidly behind but remain with open hearts and hands to religious traditions. When those on the edge of the inside and those on the edge of the outside—in my work, this means the Catholic sisters and spiritually diverse millennials—reach out to hold hands across that chasm, endless possibilities emerge.

At one of our first Nuns & Nones gatherings in the spring of 2017, a sister in the Congregation of the Sisters of St. Joseph told us that it is only on this “prophetic edge” that we are able to see the newness emerging. But in order to stand on that edge, we must hold one another up. This is the unique possibility that exists in our current moment in religious and spiritual life: acknowledging the chasms and divisions that exist—and at the same time recognizing the opportunity we have to create bridges and to forge a new way of being that our moment all too desperately needs. The Nones today can lead us to stand between tradition and innovation, to peek at what might arise over this prophetic edge.

Notes:

- Krista Tippett, Becoming Wise: An Inquiry into the Mystery and Art of Living (Penguin Books, 2016), 179.

- Isle of Wight Monastery Offers Spiritual Internships, film by Adam Paylor and Ben Moore, BBC News, August 11, 2019.

- Thomas Moore, preface to The Rule of Saint Benedict (Vintage Spiritual Classics, 1998), xxv.

- Phyllis Tickle, The Age of the Spirit: How the Ghost of an Ancient Controversy Is Shaping the Church (Baker Books, 2013).

Katie Gordon, MTS ’19, is a national organizer with Nuns & Nones, an alliance of spiritually diverse millennials, women religious, and key partners working to create a more just, equitable, and loving world.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.

This Article was so useful for me, by going through it I could find many aspects that can help increase the insights we need!

This article was forwarded to my by a Sister of St Francis of Assisi of which community I am an Associate in Relationship. The article touches on ideas that resonate with our Associate Program at this time of revisiting our relationship to a congregation of dying members. Across the nation there are thousands of men and women in partnerships with religious women’s communities. In a time when the institutionalized religion is not the path for many, associates offer a way to be contemplative, spiritual and responsive in a challenging world. We are called by the Spirit to share the charism and mission of a community and its works and transcend into the beckoning morrow. We must grow with the times because God’s Church is very very big and is calling.

Wow! This is a voice I would like to hear a lot more of. I am an agnostic educated by nuns and in the last graduating class of my catholic grades 1-12 school. What felt like the “loss” of nuns had a deep impact in our community. Then I lost my connection with the church itself because of inconsistencies I could no longer ignore. I was faced with the tough task of trying to raise my children to be good people without the strong support of a community that my parents had relied on to help raise me. Katie’s words paint a picture of hope. Regardless of where this path leads, it has begun at an excellent place. It’s like a miracle to me that there are young people and nuns having the transformative discussions we sometimes had in religion classes –transcending our religion to wrestle with open minds and curiosity about how to be a good person in a challenging world. I am glad you found each other and are sharing your journey with the rest of us.

Love this! Like you, I find the intersection of “sacred” and “secular” most compelling. I’m a Life-Cycle Celebrant and work with people of various beliefs and lack thereof to craft personalized ceremonies to honor major life transitions. Thanks for such a rich article!