Featured

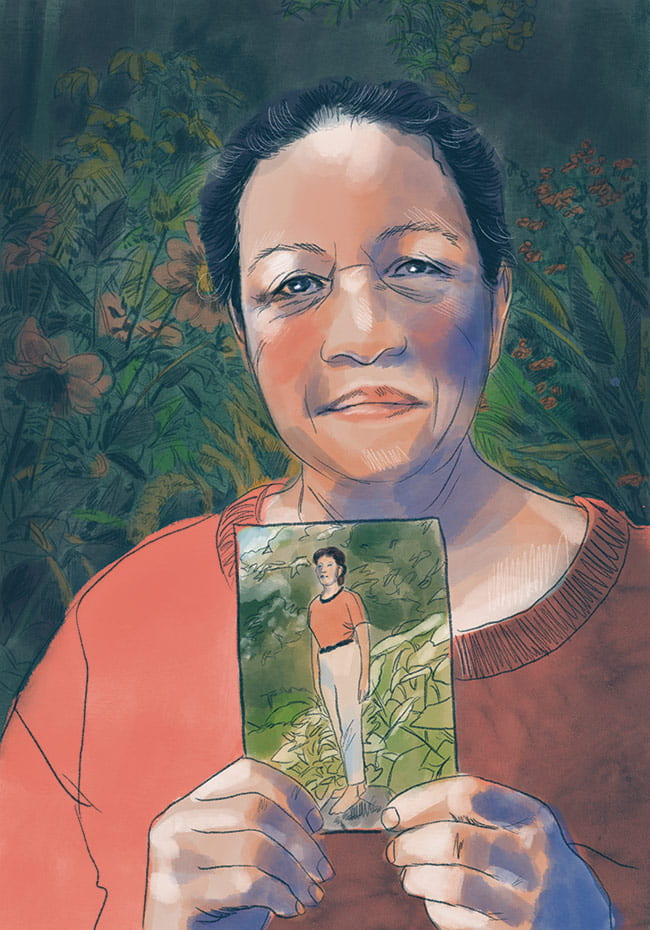

‘My Dreams Will Never Be the Same’

Neris Gonzalez will keep testifying until generals are held accountable.

Illustration by Gabriella Trujillo

By Julia Lieblich

Neris Gonzalez was watching the news when the grainy video of George Floyd appeared. She sat openmouthed as a police officer held his knee on Floyd’s neck while he gasped for breath and called for his mother. Her therapist at the Marjorie Kovler Center for the treatment of torture survivors might have warned her that she was the last person who should be bearing witness to such brutality, given her history and the kind of violence she had seen in her home country of El Salvador.

“I was in shock,” she told me during a trip to Chicago from the Texas border in August of 2020. “I was suddenly back in my cell in El Salvador when a guard put my head in a bucket of water and held me down by the neck. When people are being tortured, everyone cries, ‘Mama.’ ”

I have known Neris, a former Catholic catechist who carries a picture of the martyred Archbishop Oscar Romero in her pocket, for two decades. After I saw her testify in Florida against two leading Salvadoran generals charged with command responsibility for torture in a landmark human rights trial I covered for the Chicago Tribune in 2002, I never wanted to let her go. Since then, we have visited one another at our homes in Chicago, where she first found refuge in 1997. In 2013, we met at her apartment in San Salvador after she returned to care for her dying mother and disabled sister.

We happened to be together at a conference in March of 2003 and were watching television when the first flashes of air strikes marked the start of the Iraq War. President George W. Bush told the public that U.S. troops would avoid targeting civilians.

“They always say that,” she said, visibly shaken, “and civilians always die.”

Now 65, Neris could have retired from the activism that had once caused her to risk her life. But she has spent the past four years back in the United States working at the Texas border with Salvadoran refugees who tell her stories of gang violence and sex trafficking. And she is doing the unthinkable in a country that rarely punishes its perpetrators: she and another survivor have initiated a case in El Salvador against the same generals to bring them to justice on their home turf. Though Stanford law students conducted research in the pretrial phase of Neris’s case, at this time, the odds are clearly against her.

“In El Salvador, there have been no convictions to date of the top commanders directly ordering, transmitting, or permitting the torture, disappearances, and executions of tens of thousands of Salvadoran citizens by their own military,” Terry Karl, Stanford professor of political science and a leading expert on human rights in El Salvador, told me. But even if her case goes nowhere now, Neris and her supporters believe in publicizing a history many would rather forget.

Years ago, Neris spoke to me only because she thought a reporter might be useful in publicizing the repression in El Salvador. She never smiled and her answers were curt. We talked about the most horrifying details of her abduction with her therapist present, in case she had flashbacks. “Torture has indelibly marked me,” she said. “I’ll never be the same. My dreams will never be the same.”

Today, she laughs easily and speaks openly, perhaps because she is confident I won’t betray her, but more likely because she is buoyed by the glimmer of justice she has experienced in the U.S. courts, coming against all odds for a poor woman from a small village. She still looks the same to me, with her smooth round face, chiseled cheekbones, and hooded brown eyes. She continues to wear her long black hair in two braids decorated with colorful clips and dresses in Mexican blouses embroidered with the kinds of flowers she grows and loves.

Psychologists label it “intergenerational trauma” when children inherit the pain of their parents. Neris calls it heartbreak.

If Neris has taught me anything, it is that the repercussions of violence can last a lifetime. She is still reconciling with her two daughters, who feel betrayed because she left them behind when she had to flee her country four decades ago. Psychologists label it “intergenerational trauma” when children inherit the pain of their parents. Neris calls it heartbreak.

Neris sat quietly in a West Palm Beach courtroom in the summer of 2002, joined by Carlos Mauricio and Juan Romagoza—in a trial that bears Romagoza’s name. She wanted to be sure she wouldn’t faint or cry uncontrollably as she tried to speak. Her worst fear was that, while testifying, she would start imagining that it was 1979 again and she would be back in the basement cell. So for more than a year, she prepared for the trial by role-playing with her therapist.

As she took the witness stand, she looked squarely at the two generals sitting together across the room: the tall, confident Carlos Eugenio Vides Casanova, who she remembered grinning in his khaki uniform as he rode through the streets, and the short, somber José Guillermo García, old even when he was young.

Both were now grandfathers who had come to Florida to retire by the pool. Neris was a 47-year-old grandmother, half a lifetime away from her rural Salvadoran birthplace. She and two other Salvadorans had come to this courtroom bravely to call the two former military leaders to account for the crimes committed by their soldiers in El Salvador during the late 1970s and 1980s.

In a steady voice, she answered the questions posed by her lawyer, breathing deeply as the interpreter repeated her responses in English. “We had a fear of going outside,” Neris said, with a glance at the generals who took notes as she spoke, as if in a classroom. “We didn’t know whether we would return.”

Her pro bono lawyers had considered asking her to leave out the most harrowing details of her story, which might have seemed improbable to jurors unfamiliar with El Salvador. But in the end, they left the decision to Neris.

The soldiers came for her after Christmas, she told the jurors. Four men, three in uniform, grabbed her from the local market in broad daylight and brought her to the basement of the National Guard local headquarters. Then they took her to a room marked El Matadero, “The Slaughterhouse.”

Some months after the July 2002 trial, Neris and I sat in the kitchen of her home in Chicago’s Pilsen neighborhood. On the wall above us was a painting of Archbishop Oscar Romero, who was killed by a sniper’s bullet in 1980. She revered Romero because in his Sunday masses he denounced the military’s murder of civilians.

Plants lined the windows of the pristine apartment she shared with her daughter and 10-year-old grandson. Red chili pepper garlands hung from the kitchen walls. Neris wore a floral print blouse with jeans and sneakers, and her hair was tied in a dozen braids cinched with butterfly barrettes.

“My daughter did this,” Neris said with a smile as she shook her braids. Carolina, who at 30 was a quieter version of her mother, laughed at her handiwork. They had only recently been united after 15 years apart, and they were doing the things mothers and daughters do.

We had finished several cups of tea by the time Gonzalez began telling me about her native farming village of San Nicolas Lempa in the state of San Vincente, a place where chickens, ducks, turkeys, and roosters paraded around her family’s one-room adobe house. Her mother had taped to the wall a poster of a white Jesus with blond hair, and she put fresh roses and daffodils on her altar to the saints.

The third of 12 children, Neris went to church with her grandmother each Sunday—a large, open space with a metal roof. Her grandmother believed in the sun grandfather. She knew how to interpret messages about the future from birds, dogs, cows, and oxen and made herbal infusions to prevent bad news. But she also followed Catholic teachings, and it annoyed her that the priest said Mass in Latin with his back toward the parishioners. “I can’t understand a word the son-of-a-bitch says,” her grandmother used to say. But she went to church because that’s where God lived.

“And she wanted to be with God,” Neris said.

Her childhood was carefree, Neris wrote to me in a letter: “I ran freely in nature on the dusty street. I loved the smell of wet earth and wet ash when the peasants cleaned the land to sow corn, beans, and rice in the field and paddocks. We played as boys and girls, without fear, into the night lit up by a beautiful moon.”

She attended school until ninth grade and, at the urging of her family, left home in 1972 at the age of 15 to marry a man 9 years her senior. She gave birth to Carolina a year later, but she had never loved her husband, she said, and the two soon separated.

Neris returned home to manage the family store and work for the local church as a catechist, preparing children for their first communion. She was drawn to the pastor, Father Rutilio Grande, who was trying to improve health care and education in San Vicente. The church was alive, he told her, and Jesus lived among the poor.

Soon she was working as a health educator for the church in villages without doctors and joining people on trips to the capital city of San Salvador to ask government leaders for improvement in health care and the schools.

Neris taught her adult pupils to count…after she found out that managers were lying to their workers about the weight of the goods they were buying.

Carmen Barrera, who lived in the nearby village of Tres Calles, remembers Neris as a leader. They served together on a team that taught people to read, and Neris taught her adult pupils to count as well after she found out that managers were lying to their workers about the weight of the goods they were buying. She became known as the woman who taught peasants to count to 100.

“That’s when my problems began,” Neris says.

She was romantically involved with a university student and pregnant with her second daughter when the nation’s violence started in earnest. Throughout the country, political tension between the military and a civilian population agitating for land reform and democracy had escalated into organized state terrorism that would lead to an armed insurrection and the beginning of a 12-year civil war.

Neris first noticed National Guardsmen posted at the coffee and cotton plantations. Then villagers began finding the mutilated bodies of church leaders, labor organizers, health workers, and students lying in the road.

“Every night you would see bodies on the street,” she says. “You would open the door and see a body in front of the house. The National Guard wouldn’t allow us to bury the bodies, so the dogs and vultures ate them.”

“We didn’t sleep after that,” she says. “We would watch the children sleep.”

Father Grande in his Sunday masses began denouncing the killings and the political oppression by the military, which had always served the wealthy elite. The homily that may have sealed his fate was delivered in February 1977. “The very violence they create unites us and brings us together even though they beat us down,” he told the congregation.

On March 12, 1977, security forces carrying machine guns ambushed Father Grande’s vehicle, killing him along with an elderly man and a disabled teenage boy.

Archbishop Romero, stunned by the murders, canceled all masses in the archdiocese to hold a memorial service—despite protests from the military government, as well as from the Papal Nuncio and conservative Catholics in San Salvador. “Whoever touches one of my priests has to deal with me,” Romero warned.

But Neris thought: “If they killed the head of a church, what is going to happen to us?”

In 1979, she watched television as the new minister of defense, General José Guillermo García, and the new head of the National Guard, General Carlos Eugenio Vides Casanova, promised reform. But the terror only escalated.

A close friend from her church was abducted from a bus at a National Guard checkpoint. The next day, neighbors found her decapitated body. On December 26, 1979, the soldiers seized Neris, then 23, in a market near San Nicolas Lempa. Ignoring the shouts of vendors, they pulled her from the food stalls and took her to the basement of National Guard headquarters in the city of San Vicente.

There, over the next two weeks, the guardsmen asked her again and again why she had taught peasants to count, and whichever way she answered, they stuck pins under her fingernails. They cut her with razor blades, slashed her with a machete, and burned her with cigarettes. They immersed her in freezing water for hours at a time.

At one point she was forced to lie under a metal bed while four men sat on the sides and rocked back and forth trying to crush her unborn child. For two weeks, guards took turns raping her.

The guardsmen brought her to a room caked with blood, where they made her watch as they tortured other captives. When the men gouged out the eyes of a teenage boy and thrust a machete into his stomach, she fainted.

Neris does not remember anything after that, neither her captors bringing her near-lifeless body to a garbage dump nor the first months she spent in a clandestine clinic in San Salvador. She couldn’t talk or understand what people said to her, and she has no memory of giving birth to her son, who died soon after. Only when she gained full consciousness six months later did she learn that her baby was dead and her father was among the thousands of desaparecidos, those who had disappeared.

Barrera didn’t see her friend until she returned to the state of San Vicente. “Neris looked very bad and she was always crying,” she recalls. “She had scars on her arms where they burned her. She couldn’t sleep because every time she fell asleep, she would see the same guard who came and tortured her.”

Neris wanted to go home to San Nicolas to see her daughter, but it was too dangerous. She was afraid the National Guardsmen would find out that she had survived and come after her and her family. “So she went from community to community and stayed at my house,” Barrera said.

Neris decided to work with an organization that helped Salvadorans rebuild communities destroyed by the war. Barrera thought it was too soon. “But there were no other options,” she said. “Neris couldn’t be in her family home. We thought it would be better if she stayed active.”

Being around her people, she says, “was the only way I would feel alive. I had no idea why I had survived, but I thought maybe God had a mission for me.”

Neris agreed. Being around her people, she says, “was the only way I would feel alive. I had no idea why I had survived, but I thought maybe God had a mission for me.”

She threw herself into environmental work as an unarmed civilian in areas controlled by the Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front, the leading opposition that formed in late 1980. She helped found a women’s cooperative that planted crops on land that had been burned and worked on a project to make soap from seeds.

On the surface, it looked like a remarkable recovery. But she couldn’t remember having a full night of sleep. She would stay awake in case the National Guardsmen returned and to avoid the recurring nightmares.

“I used to see images of my dead child,” she says. “He came, and I followed him.” And day after day she missed her daughters, who were being raised by their grandmothers.

Even the cease-fire more than a decade later brought her little peace. “There was stillness, but I heard the noise inside my head of the bombings, the rockets, the missiles,” she says. And a sound or a smell, like the stench of spoiled meat, could bring her back to that basement in San Vicente.

In 1995, Neris married another survivor, Jorge Montes, a former Dominican seminarian. Much of the time, Montes said, she seemed content, but she was slow to trust, and the nightmares showed no signs of abating. “Torture has no remedy,” he says.

With her husband, Neris finally returned to visit San Nicholas Lempa. Her oldest daughter barely knew her, and the younger one did not recognize her at all. Neris began to wonder if, after all this time, she could ever rebuild her life.

“I remember standing on a hill looking at people who had witnessed the massacres and destruction,” she says. “I felt as if I were standing on ashes, and I fell into a deep depression.”

Scott Wright, a Catholic lay missionary from the United States living in El Salvador, was sure she needed help that she would not be able to get in her own country. Religious groups in the United States paid for her airfare so she could begin treatment in Chicago at the Kovler Center, which provides trauma-informed care to refugees and survivors of torture. Father Charles Dahm, the pastor of St. Pius in Pilsen, provided housing for her and Montes in an empty convent.

“It was a convent, a church: that was important,” Neris says. “The place brought serenity into my life.”

Irene Martinez, an internist at Cook County Hospital, gave Neris her intake physical in 1997.

“When I first saw her she was having a lot of flashbacks and hallucinations of the place she was tortured,” Martinez recalls. “I found scars of different shapes, consistent with her story of different traumas: being burned with cigarettes, being cut with a machete, and being cut with razor blades. I didn’t have any doubts about her story.”

Neris attended therapy three times a week to help her develop a sense of safety and trust, establish ties with a community, and gain a sense of self her captors had tried to destroy. It would take a year before she could talk about her trauma.

Neris attended therapy three times a week to help her develop a sense of safety and trust, establish ties with a community, and gain a sense of self her captors had tried to destroy. It would take a year before she could talk about her trauma. “It’s not just reopening a wound,” she says. “It’s reliving the torture so you can understand it.” After some sessions she would be so disoriented she needed to be accompanied crossing the street so she would not be hit by oncoming cars.

In her free time, she planted tomatoes and red peppers in the convent backyard and brought in chickens, ducks, and other animals she had loved in El Salvador, and she began teaching classes in nutrition, farming, and ecological awareness.

The children loved the animals. Some adults complained when Neris brought two roosters to church during Sunday Mass. She countered, “Most people would rather hear a rooster than gangs shooting guns.”

Father Dahm marveled at the faith of a woman who never asked Where was God? during her suffering. “She knows God has nothing to do with it,” Dahm says. “She’s totally on board with the vision of God as liberator. We have to pursue justice no matter what it costs.”

In 1998, attorneys from the Lawyers Committee for Human Rights, a New York–based advocacy group that supports the prosecution of war crimes, were surprised to find that two of El Salvador’s leading generals had retired to Florida. While they were not the trial attorneys, they argued that this meant it was possible to bring a suit in the United States under the Alien Torts Claims Act and the Torture Victims Protection Act, which allows civil claims against foreign human rights violators.

The relatives of the four North American churchwomen, who were raped and killed in El Salvador by members of the El Salvador National Guard in 1980, were the first to bring a case against the two generals, based on the doctrine of command responsibility. The generals, the plaintiffs argued, knew or should have known about crimes committed by troops under their command but failed to try to prevent atrocities or punish the offenders.

Neris worried that testifying would put her family members in danger and that she would not be able to bear being on the witness stand, but she decided to join the suit on behalf of Salvadoran survivors who had to find ways to heal without justice. “Without [testifying in] the case, my therapy would have been about words, not action,” she said.

During the first trial, the lawyers for the churchwomen presented cable after cable showing how the generals knew of atrocities but failed to stop or investigate them, but the sheer amount of material confused jurors. The generals testified that because El Salvador was in a state of chaos, it was impossible to control rogue soldiers who tortured and killed civilians, nor did they have the resources to investigate crimes. While this was not the case, the jurors had no clear way of understanding the responsibility of top commanders.

The jury sided with the generals. “I felt just anguish, just anguish,” jury foreman Bruce Schnirel told me afterwards. “I just wish it had been a better case that demonstrated the generals could control their troops. I am scared to death . . . people will think they can get away with murder.”

Human rights lawyers worried about what the decision would mean for future civil cases that relied on the doctrine of command responsibility. “The outcome is worse than no trial at all,” human rights lawyer Douglass Cassel said at the time.

Still, when the Center for Justice and Accountability took responsibility for a second trial and asked Neris if she would participate, she agreed.

Nearly two years later, Neris sat on the witness stand and scanned the wood-paneled courtroom to find the faces of her therapist and her daughter Carolina.

“I hope I have the strength to tell you, ladies and gentlemen of the jury, what happened to me,” she said.

After five years of therapy, Neris could speak without fainting. She told the jurors about the rapes, the burns and cuts, and the savage mutilation of a teenage boy in a room covered with blood. And she described how two guardsmen had forced her to lie on a metal bed while they rocked back and forth on her belly.

“I was feeling my own torture, and I was also feeling the torture of my son,” she said, as she dabbed her eyes with a handkerchief. “I was almost dead, thinking of my son.”

The burden for the pro bono lawyers in this second trial was to make a more convincing case that the generals had command responsibility, that is, that they were in command of the actual perpetrators. Stanford political science professor Terry Karl described to the jurors a rigid chain of command, showing illustrations and documents. She made the clear and compelling argument that the generals were aware of the offenses being committed by their troops, that they were in full control of their soldiers, and that they failed to prevent crimes or punish any perpetrators. She called this “a green light” for the commission of atrocities.

The jurors asked the judge if they could see Neris’s scars. She showed them the razor slashes and cigarette burns on her arms.

Then, in an unusual move, the jurors asked the judge if they could see Neris’s scars. She showed them the razor slashes and cigarette burns on her arms.

On July 23, 2002, the jurors signaled that they were ready to announce a verdict. The plaintiffs and their lawyers held hands as they entered the courtroom. The jury found the two generals responsible on all counts for the atrocities committed by their subordinates. They were ordered to pay $54.6 million to the plaintiffs, which proved almost impossible to collect. Neris and the other plaintiffs would receive only a fraction of the actual award.

“For 28 years since the torture, I’ve been waiting for justice,” Neris said. Then she turned to the jurors and whispered, “Thank you, thank you,” as she raised her arms in triumph.

One of her lawyers said Neris was born with a life force that keeps her going.

“I think it’s a love of the people, the community, the children,” Neris said. “I have faith that gives me strength to overcome whatever obstacles I find. The generals pray to a rich God. I pray to a just God. The trial was the best therapy. But this victory is not enough. We need more victories.”

Eight months after the trial, I had a rare meeting with the generals. A statue of the Virgin Mary stood outside the home of García’s beige stucco home in Florida. Inside, he and Vides Casanova sat on a couch next to a foot-tall statue of Jesus.

“We pray for Neris Gonzales,” said García. “I hope she is convinced one day she has taken the wrong position.” He and Vides Casanova, he said, had helped reform a military and a country in turmoil, with the support of the U.S. government, which gave them political asylum in 1987. To prove their point, they showed me scrapbooks of photos of themselves posing with U.S. military leaders. They had not known about torture, they claimed. They had saved the country from communism and given democracy to the people.

But in 2015, their pasts caught up with them. The war crimes unit of ICE deported them to El Salvador after formal U.S. government hearings for violating human rights. Today, General García is on trial in his own country for being the top commander and the minister of defense during the 1981 massacre of El Mozote, the largest contemporary massacre in Latin America.

The most recent push for accountability in Salvadoran courts has focused on the El Mozote case. In December 1981, the Salvadoran army had deployed an elite battalion to El Mozote, killing almost one thousand unarmed civilians, including at least 553 children. In pretrial hearings in April 2021, Terry Karl once again testified against General García, the defense minister during Neris’s torture. This time, she showed how the Reagan administration covered up the massacre to guarantee the continuation of U.S. aid to the Salvadoran military. She demonstrated that a U.S. military advisor was with the direct commander who ordered the massacre and that the advisor had written colleagues that he was at the site of the violence. Neither the U.S. Department of Defense nor the Salvadoran administration will provide full records of the El Mozote massacre to the presiding judge.

The prospects for this trial, like so many others, have only dimmed since Salvadoran President Nayib Bukele carried out a constitutional coup on May 1, 2021.

As the Washington Post reported, Bukele used his congressional supermajority to fire the country’s top court and attorney general. By the following morning, he had replaced them with his loyalists, who support impunity. “In one fell swoop, Bukele gained near-total control over all three branches of the Salvadoran government.”

The coup, combined with Bukele’s alliance with the current military leadership, means “such trials may prove unlikely in the future,” Karl said.

After years of witnessing more defeats than successes in the long arc toward justice, she maintains her commitment to bringing public attention to the terror she carries in her body and soul.

Knowing all of this, once again I worried Neris would lose heart, and once again I was wrong. After years of witnessing more defeats than successes in the long arc toward justice, she maintains her commitment to bringing public attention to the terror she carries in her body and soul. And she holds on fiercely to every win.

One warm day in the fall of 2020, Neris and I took off our masks to enjoy bowls of pasta at an outdoor restaurant in Chicago. She had something surprising to tell me, she said. She was leaving for Texas to spend three months with her youngest daughter, now 40, whom she had not seen for more than a day in almost two decades.

Neris asked me not to mention her daughter’s name or the town she lived in. She had endured enough publicity during the trial.

Her daughter was just one year old when her mother left the country. Raised by her grandmother, she had endured her own psychological problems as a result of living through war and the disappearance of her mother, more evidence that trauma passes from parent to child.

After Neris’s daughter settled in the United States, she refused to answer her mother’s calls. Only after she completed a course of therapy with an Argentine therapist who understood the dynamics of war did she reconsider.

“She wants to see me,” Neris said with an uncharacteristic giddiness. “I am going to live near her and her family.”

The reconciliation went smoothly, Neris reported when she came back to Chicago. Gradually, the two unfolded the details of their lives in conversations over dinner and long walks in forest preserves, along borders, and during trips to neighboring towns. It was a start.

“I have my daughter,” Neris told me, further proof her torturers did not win.

More good news followed. On April 20, 2021, the jury reached a verdict in the Derek Chauvin case. After 10 hours of deliberation, the jury found him guilty on all three counts, making him the first white Minnesota police officer to be convicted of murdering a black person. As soon as I heard, I called Neris.

“No!” she said. “No!”

Finally, she caught her breath and turned on the television.

“A victory against impunity,” she cried. “Wow! A victory for justice.”

Julia Lieblich, MTS ’92, is the author of Wounded I Am More Awake: Finding Meaning after Terror. This article was produced with the support of the USC Center for Religion and Civic Culture, the John Templeton Foundation, and Templeton Religion Trust. Portions of this article originally ran in the Chicago Tribune.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.