In Review

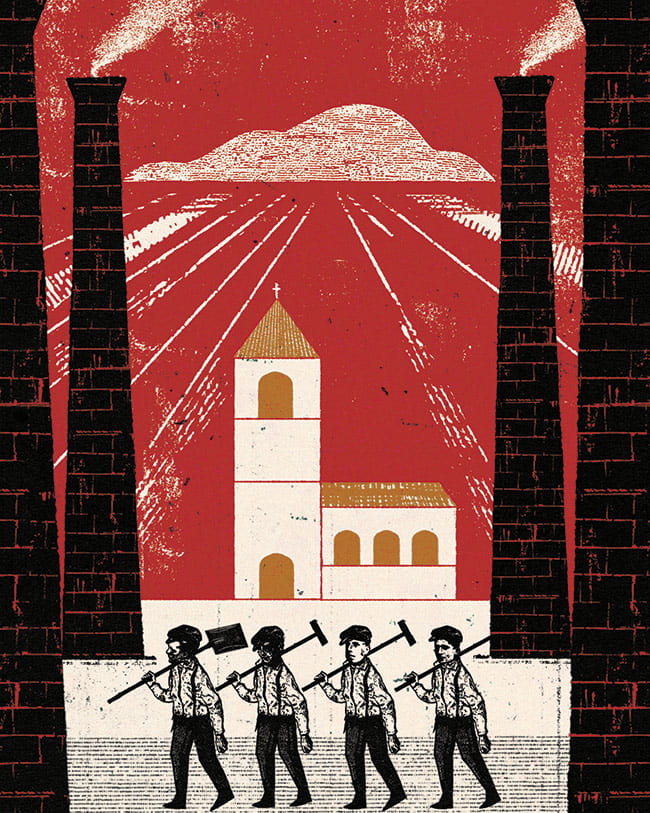

Calvin, Capitalism, and Predestination

By Michelle Sanchez

Benjamin Friedman’s Religion and the Rise of Capitalism argues that economics has been influenced by religious ideas from its inception and at every subsequent stage of its development. Friedman demonstrates this through a series of largely chronologically ordered chapters that show, first, that moral philosophers and political economists held religious worldviews that indelibly shaped the discipline, and second, that economics continues to be shaped by the ongoing impact of religiously shaped public opinion. After hundreds of pages of carefully gathered and meticulously rendered evidence, it would be difficult to contest this central claim. Indeed, one might wonder how it was possible for the relationship between religion and the modern disciplines to have fallen from the status of an obvious fact, but that would be the topic for another book.

What Friedman’s book does invite readers to consider, however, is the question of how best to characterize the nature of the relationship between religion, the order of worldly life, and the disciplines that have formed in order to study and characterize worldly life. A few big questions emerged and guided my reading as I moved through Friedman’s chapters. For one, it was interesting to track what “religion” is in this book. What are its qualities and its boundaries? The specific mode of religion under consideration is, understandably, primarily Protestantism. Protestantism has been the hegemonic Christian expression of northwestern Europe and the settler states of North America since before the Enlightenment. But even within those constraints, we could ask whether “religion” is best approached as a record of beliefs that people hold or as a record of the ways institutions have organized beliefs. What is the relationship between the two, and what important features of religion does the centrality of the category of “belief” leave out?

Another question is whether and how religion is functionally distinguishable from “worldview.” The book reiterates Einstein’s definition of worldview, which is a “simplified and easy-to-survey image of the world” that helps people make sense of fragmented experience. But if religion is a worldview, then can it be distinguished from, say, discourses on racial and cultural difference that were produced by many of these same figures—Hume, Smith, Cotton Mather, Josiah Strong? Of course, religion involves all of this and more, and scholars inevitably need to isolate aspects of religion for analytical reasons. This means that the bigger question Friedman’s book poses is how best to approach and constrain “religion” for the purpose of understanding its relationship to other realms of life that our university disciplines treat as different, like economics and politics. What parts of religion should we self-consciously isolate to tell that kind of story?

As a scholar who focuses on theology, I’m perennially interested in this question. Theology is often isolated problematically, treated as a written record of beliefs that define one’s religious identity, in the event that one accepts them. But I find this undermines our ability to understand the way theology actually shapes lives, imaginatively, habitually, and collectively. I’m interested in the way theological writing interfaces with broader human concerns, both at the site of its initial production (Why did a person decide to sit down and write? What was going on that they worried about?) and its diffuse reception (Where do we see theological images and ideas operating more broadly in politics, society, and art? Under what circumstances do some ideas become compelling?).

Weber’s claim has been so widely cited and so widely contested in part because it offers a clever answer to a puzzling question, which is why capitalism seemed to flourish in Calvinist polities.

For this reason, I want to think with the book’s most pronounced claim about theology: that the rise of capitalism in England and the United States correlates with the rejection of predestinarian thinking and orthodox Calvinism; and that predestination is largely incompatible with a religious disposition that supports the pursuit of happiness, moral self-improvement, and the ability to choose and build a better society. This claim is a striking contribution to the literature in part because it contrasts with Max Weber’s famous claim that predestinarian Calvinism generated a set of habits and affections congenial to modern capitalism. Weber’s claim has been so widely cited and so widely contested in part because it offers a clever answer to a puzzling question, which is why capitalism seemed to flourish in Calvinist polities, and thus how a quasi-deterministic religious cosmology could generate conditions for unprecedented human self-assertion. As Erasmus of Rotterdam pointed out in his diatribe against Martin Luther in 1521, the opposite should be true. People should seek to improve themselves and their situation only if they believe it is possible to do so, if they believe that at least some part of the power lies in their own hands. According to Weber, predestinarians worked so hard—and reinvested—because they were desperate for signs of their eternal election. You can’t earn your salvation with work, but you can see evidence for your chosenness in the fact that your efforts are blessed with success. And because greed is a sin, one ought immediately to recirculate one’s earnings into work for the common good.

Weber’s argument, ingenious as it is, has been routinely contested on a number of grounds, many of them historical, some of them theological (such as the fact that few major theologians ever taught anything like this). Friedman’s contribution to this critical literature is grounded in an analysis of religious belief that is simultaneously broader and more fine-grained, alerting us to internal debates within Protestantism. Specifically, the driving forces for the emerging science of free markets were nearly always aligned with anti-predestinarian Christianity or deism. This allows for a more intuitive account of how religion influenced the formation of a discipline: less predestination = more positive emphasis on human activity, all while infusing human activity with religiously informed confidence in the goods of social improvement and personal enjoyment. While Friedman accurately points out that the rejection of predestination on an individual level does not necessarily entail the rejection of predestination on a collective level—that is, at the level of the nation or the civilization—I still wonder whether this equation doesn’t end up putting too fine a point on the power that predestination holds, even in our current ideological landscape.

Let me explain what I mean, beginning with Calvin, the figurehead of modern predestinarian Christianity. I’m often struck by the contrast between Calvin’s own theological articulation and the way he gets summarized. On this count, the book is just the messenger: as Friedman records, later historical proponents and exponents of Calvinism did sometimes summarize Calvin’s ideas in ways that emphasize a pessimistic view of human nature and a deterministic view of worldly events. But I generally find that attention to Calvin’s writing adds nuance, aiding our understanding of why Calvin might have drawn on certain ideas in his own context and—importantly—how these ideas might operate in surprising ways in later contexts. Jean Calvin (1509–1564) was a French humanist who was a great admirer of the Roman Stoics. He believed that well-ordered laws were necessary to cultivate public good beyond the bounds of the church. He was also invested in the power of rhetoric to stun and readjust the flawed process of human perception. His writings show that he pursued something like Stoic philosophical exercises to train the reader to better perceive the world and respond to challenges, including challenges posed by our own depravity.

When Calvin talks about depravity, he is using the Latin term pravitas, which simply means crookedness. Pravitas is never “utter” depravity, but “total” depravity, meaning that no part of the human is left untouched. This doesn’t mean humans are utterly evil, just that we perpetually “miss the mark.” This phrase, which for some might recall mornings spent in Reformed Sunday School, is easy to spot as an archery metaphor referring to bent wood. But it also had a more precise meaning in Calvin’s own intellectual context. Calvin was among those humanists who popularized a model of perception shared by authors like Montaigne and Hobbes. According to that view, the world of experience is characterized by perceptible “marks” that cognition comes to understand as “signs,” meaning that “missing the mark” also has to do with the human inability to be certain about that which one sees. While Calvin’s thinking on sin is obviously indebted to Augustine, it must also be contextualized alongside the early modern skepticism soon to be embraced by Montaigne and Hobbes (and targeted by Descartes). Like other humanists of his time, Calvin was interested in a use of rhetoric to accommodate and improve the senses. In fact, the first part of the Institutes to be translated into English was Calvin’s chapter on the Christian life, with instructions on how to bear suffering joyfully.

It didn’t seem to occur to Calvin that predestination or depravity would be an impediment to human efforts at self-improvement.

The point, here, is that it didn’t seem to occur to Calvin that predestination or depravity would be an impediment to human efforts at self-improvement. In fact, when he argues that divine providence actively wills everything that happens, he also insists that

We are not at all hindered by God’s eternal decrees either from looking ahead for ourselves or from putting our affairs in order, but always in submission to his will. The reason is obvious. For he who has set the limits to our life has at the same time entrusted to us its care; he has provided means and helps to preserve it; he has also made us able to foresee dangers; that they may not overwhelm us unaware, he has offered precautions and remedies. Now it is very clear what our duty is: thus if the Lord has committed to us the protection of our life, our duty is to protect it.1

Part of the difference here is that Calvin thinks the knowledge of God is intertwined with knowledge of ourselves, meaning that all knowledge of God is also useful and beneficial to us. (If you do a word search for “use” and “benefit” in an e-book of the Institutes, you’ll get a lot of hits.) Because of this, Calvin thinks that knowledge of God’s decrees is exactly what enables the most useful and beneficial kind of human action. We won’t be happy or motivated to act unless we have some confidence that something good or meaningful is going to come from our action, and that is what Calvin thinks God offers.

The recognition that we operate within conditions that we did not choose can also provide profound moral and therapeutic effects, especially if we believe a benevolent will is securing our destiny.

If nothing else, a closer reading of Calvin alerts the reader that predestination can be powerful in a way that can be counterintuitive, though perhaps not always in the way Weber suggested. As much as people seem instinctively irritated at the suggestion that they’re not in control of their own destiny, the recognition that we operate within conditions that we did not choose can also provide profound moral and therapeutic effects, especially if we believe a benevolent will is securing our destiny. If you find yourself on top of the world—maybe you’ve moved up several ranks of social class and earned the admiration of peers and a comfortable living situation—it might be tempting to say that you did it all yourself. But there are good moral reasons for acknowledging all of the factors that helped along the way: the support of others, grace, privilege, dumb luck. This can be therapeutic too, because there’s nothing that provokes anxiety quite like the sense that everything depends on you and your ability to control every contingency and plan for every little detail, and that one bad choice could destroy everything.

So when I was working my way through the middle chapters of Religion and the Rise of Capitalism, especially the chapter on the clerical economists, I could not help but think of how the rejection of predestination might be very bad news for anyone who has struggled. Someone like John McVickar might not call you totally depraved, but he would call you a “machine out of order” (253). Even Abraham Lincoln might not invoke predestination to categorize your soul, but if you remain a laborer all your life, he would suggest you may “have a dependent nature which prefers it” (274). If you find yourself on the wrong side of progress, it’s not always clear which approach represents the more “horrible decree”: the idea that material progress is the meaning and end of life and that it’s your fault you failed might be worse than the idea that God’s mysterious will determines who is in or out. While thinking with the book’s claim that the rise of capitalism is correlated with the rejection of predestination, I also wonder if some of the power of that doctrine isn’t continuing to drive how we imagine and justify economic distribution today.

I have already said that Calvin presents divine providence as something that should motivate human action and bring happiness and comfort. The idea that God is in control can relieve decision-anxiety and provide hope that everything isn’t mere chaos. Some of what Calvin says is actually quite in line with “the law of unintended consequences”—that, for example, a human can act out of an evil will but God directs it to a good result.2 But what about predestination in particular: the idea that God chooses some and rejects others? It was Calvin himself who first called this the “horrible decree” (decretum horribile).3 But he still promoted the idea for a number of reasons: it is in scripture; it was taught by his theological hero, Augustine; it makes us humble.

But one often-overlooked reason for adopting the teaching has to do with a social problem that remains relatable today. How is it that not everyone sees things in the same way? Why do people not agree on basic facts? How is it that ideas that might disgust me are attractive to others, even to members of my own family? There is a sense in which Calvin simply sees predestination as the best explanation for a common-sense problem. Some people hear the gospel and are converted, other people hear the gospel and remain unmoved. While it is true (and unfortunate) that Calvin did sometimes speculate on the proportion of elect to reprobate, he also taught that you can only know your own election, and you should wish that everyone is elect.4 After all, Saul who persecuted Christ quickly became Paul, the most prolific apostle of Christ.

I wonder if some secularized version of predestination doesn’t still operate to sanctify the status quo of success stories while everyone who has failed can be categorized as a faulty machine.

In abstract form, the bigger question of difference remains with us. Some people do well with little, other people squander what they do have. Some countries thrive, other countries struggle. I’m not an economist, but I am aware that the reality of capitalist success is often predicated on the continued exploitation of others. I wonder if some secularized version of predestination doesn’t still operate to sanctify the status quo of success stories while everyone who has failed can be categorized as a faulty machine. This effectively postpones a reckoning with things like the ongoing legal and material effects of settlement, enslavement, and colonization. Predestination can be tempting for its explanatory power, whether we consider it to be God’s choice, or nature’s choice, or culture’s choice—reprobation, or a faulty machine, or a dependent nature, or something like civilizational inferiority.

There is also a flip side, the fact that the doctrine continues to hold a powerful appeal for those who want to achieve recognition or upward mobility. How often do Americans fall for the “chosen one” narrative? Neo, the unfulfilled office worker who finds out he’s “The One.” Fill in the blank with just about any superhero who learned his or her destiny from suffering conditions not of their own choosing. It is no accident that when Calvin decides to adopt a very strong version of predestination, he is living as a refugee, outside the bounds of recognition afforded by both church and state. And he is writing for a community of refugees, giving them a path to know themselves not only as legitimate but as chosen by God for a special purpose.

I was fascinated by the extent to which Friedman’s book showed the relationship between the rejection of predestination and the adoption of postmillennialism, especially as Manifest Destiny, or the continuing idea of America’s “special calling.” The idea of a “chosen covenant community” with world-redeeming ambition is common within Reformed Christianity, a tradition that began with a diaspora of refugees and religious minorities, many of whom became settlers. It should not be surprising that those on the deck of the Arabella, or those pressing into the western frontier, might have reached for the idea that God chose them for such a task and would see them through the hardship. This, of course, involved legitimizing violent authority over peoples who essentially fill the reprobate slot.

The book rightly shows that predestination was rejected on an individual level only to reappear on a collective level.

The book rightly shows that predestination was rejected on an individual level only to reappear on a collective level. For Lyman Beecher, the world needed a “new creation” that was free to take action, and that new creation was the collective person of the nation, assumed, as the book notes, to be white, male, and Protestant. According to Beecher, “The history of our nation is indicative of some great design to be accomplished by it” (275). According to Herman Melville:

We Americans are the peculiar chosen people—the Israel of our time; we bear the ark of the liberties of the world. God has predestinated, mankind expects, great things from our race; and great things we feel in our souls. . . . Long enough have we been sceptics with regard to ourselves, and doubted whether, indeed, the political Messiah had come. But he has come in us, if we would but give utterance to his promptings (281, quoting from Melville’s White-Jacket).

Friedman suggests that this kind of language signals a transition away from individual predestination to collective chosenness. The question I am left with, however, is whether those two things can really be separated.

Consider the christological imagery in these quotes. For the Apostle Paul, the saved are a “new creation” because they no longer live through Adam but through Christ. When we are speaking of Christ, there is no contradiction between work and predestination and salvation. Christ’s work saves those whom Christ chooses. In the passage quoted above, however, the role of Christ is filled by “us”: the representative race that acts and makes decisions on behalf of others. Clearly, many Anglo-Americans—Christian, deist, otherwise—rejected what they took to be the orthodox Calvinist doctrine of predestination. But did they actually reject this web of ideas, or adapt them? I’m suspicious. In my experience, theologies exist in a kind of ecosystem. Big ideas about God, humans, the world, and the relationships between them become vivid and compelling when they make possible a kind of life. Ideas change along with times and circumstances, but unless you successfully deconstruct the question itself—for example, the question of why some people see a truth that others simply do not see—the idea that resolves that question will keep reemerging in some form.

I suspect what we see in the disavowals recorded by Friedman is not a secularization by subtraction, by eliminating predestination, but a secularization by transference of properties. The kind of human who rationally acts for their own glory and who represents the good of progress is not predestined but occupies the role of the predestinator: a secularized Christ.

One of the great contributions Friedman has made is to document the many reconfigurations of Protestant Christianity that share some symbiosis with economic ideas. As someone who is similarly engaged by these questions from the theological side of the university, Religion and the Rise of Capitalism leaves me with thoughts about methodology. I think what this study offers is something beyond mere correlation. It is an invitation to think diagnostically about the fluctuations of religious ideas alongside the fluctuations of life and position. Theologies don’t just change to reinforce or resist contemporary projects, as if human beings were entirely self-transparent users of a fixed set of ideas. In the ecosystem of ideas, the rise and reconfiguration of theologies also reveal something about the concerns, fears, aspirations, and social locations of the groups whose lives animate this web of ideas in their own time and place. It is not just about leaving predestination behind, but, rather, it is about looking for how and where it might reappear, and what that tells us about our social landscape.

Michelle Sanchez is Associate Professor of Theology at Harvard Divinity School and author of Calvin and the Resignification of the World: Creation, Incarnation, and the Problem of Political Theology (Cambridge University Press, 2019). Her next book project examines the pedagogical reconfiguration of Christianity as a “worldview” in the twentieth century, with special attention to nineteenth-century Calvinist theologians.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.