Dialogue

Jesus on the Border

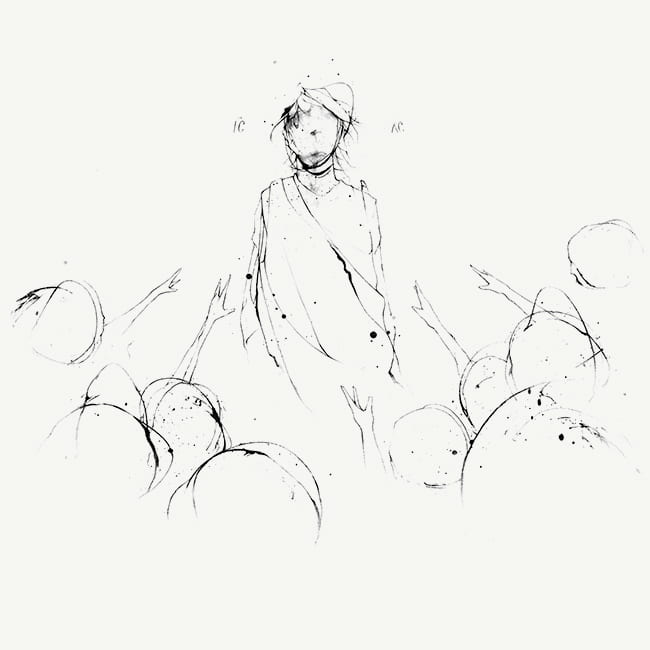

Illustration by Andrew Zbihlyj

By Ananda Rose Robinson

Imagine Jesus standing in the desert. Not one of the many deserts in Judea or Galilee, but standing in the Sonoran Desert on a steamy summer July evening in the year 2010. Let him wear what you want—white robes, or shorts and a T-shirt—and let him look how you imagine: hirsute or cleanshaven, dark-skinned or light-skinned. Perhaps he is out for an evening stroll, to empty his mind, or to consider the majesty of the saguaro cactus and the light of the low sun on the red land.

Now imagine that Jesus sees a small group of illegal immigrants stumbling toward him from afar. They look thirsty and confused. He is not uninformed. He knows of the thousands of migrant deaths that have occurred in the Sonoran Desert over the past decade. He knows, too, that they have crossed the border illegally, violating federal laws. He knows that United States immigration policies are outmoded and inefficient and that, in the absence of any sort of visionary reform, people are going to extremes: Migrants are risking their lives and dying, while the U.S. government is trying to wall off the border.

What would Jesus preach in the hills and valleys of southern Arizona? Would he take an ax to the border fence? What would he tell supporters of Senate Bill-1070, or say to the Minutemen, or to Border Patrol agents? Would he stand in the desert and tell the migrants to return home? Or might he echo Paul’s words and declare, just as there is no Jew or gentile, no slave or free man, no male or female, neither is there Mexican or American, citizen or alien, legal or illegal?

While it might seem to be an entertaining exercise to ask what Jesus would do about the current immigration mess, the question is in no way frivolous. In a country in which 78 percent of Americans consider themselves Christian,1 ideas about Jesus carry political import.

Talk to Christians at the border and you will see this firsthand. The name of Jesus is invoked to support a range of opinions, from eradicating the border to walling it off entirely.

For example, a member of the faith-based aid organization No More Deaths was clear on his answer of what Jesus would do. “He would welcome them, no doubt,” he said at a pro-immigrant rally in front of the DeConcini U.S. Courthouse in Tucson, Arizona. “It’s all over the Bible: love your neighbor, help the stranger, treat the least of these with utmost compassion. Folks like the Minutemen have no biblical grounds to argue their case.”

But talk to Al Garza, former national executive of the Minuteman Civil Defense Corps, and he will tell you a different story. “Sure, you gotta be nice to your neighbor, but that doesn’t mean ignoring the rule of law.” Echoing Romans 13, Garza said: “The law is a gift from God. We are called as good Christians to follow the law. Jesus would understand that.”

A Catholic nun I spoke to in Mexico said: “Jesus knows: There are no borders. There is only the kingdom of God.” She has spent the last decade working at migrant shelters throughout Mexico and says she has no qualms trying to help migrants enter the United States illegally.

It seems that a lot of folks are certain of what Jesus would do. But how is one to know, especially because what Jesus would do depends on which Jesus one is talking about. The Jesus of history, or the Jesus of faith? And, if of faith, which version of faith? Protestant, Catholic, Mormon, Orthodox? The Jesus according to Luke, or the Jesus according to John? The Pauline Jesus, or the Jesus of one of the early church fathers?

Ideas about Jesus are like the five loaves and the two fish that fed the 5,000: they are ever multiplying.

Even Richard Dawkins, whose 2006 bestseller, The God Delusion, referred to religions as mind viruses and the idea of a personal god as insanity, calls himself an “atheist for Jesus.” According to the Oxford biologist, Jesus was an icon of radical super-niceness, exhibiting a form of compassion that Dawkins calls “just plain dumb,” because it managed to subvert all the Darwinian nastiness required for the survival of the fittest.

But what would Dawkins’s “supernice Jesus” do when confronted with a group of migrants in the desert? Certainly he would provide immediate first aid (water, food, bandages), but would his ethic of radical super-niceness translate into a message of universal welcome to migrants who come illegally?

The Lukan story of the Good Samaritan is often quoted by faith-based immigrant rights groups like No More Deaths and Humane Borders to justify their humanitarian work in the desert and to protest border enforcement policies. The Samaritan transgressed the social and religious norms of the day by providing aid and refuge to an ethnic foe, a Judean. The unexpected hospitality of the Samaritan exemplifies Jesus’ idea of neighborliness. It is an idea that can be traced back to the calls in Leviticus (19:18, 19:34) to love one’s neighbor as oneself, and to treat aliens with unyielding compassion.

While many Christian leaders in the United States have been divided on other hot-button issues, such as abortion and gay marriage, many have discovered a united front on the subject of immigration. Christian groups from liberal United Church of Christ (UCC) congregations to ones from the more conservative denominations that make up the National Association of Evangelicals have turned to Jesus’ radical ethic of compassion as a reason to promote federal immigration reform that favors amnesty and enables more humane border policies.

Of course, there is no way to know what Jesus would do. Since Jesus made his appearance, his name, words, and story have been invoked to support innumerable causes and principles, some of which could not be more opposed to one another. “Beware of finding a Jesus entirely convenient to you,” warn the scholars of the Jesus Seminar in their book, The Five Gospels: The Search for the Authentic Words of Jesus.

In the end, maybe Jesus would do something about immigration that we cannot even envision. If there is one thing that most people agree on, it is that the figure of Jesus had a knack for the unexpected. Many of his most memorable sayings advocated reversals of social logic meant to shock his audience: Love your enemies; if someone takes your coat, give him your cloak too; offer the other cheek if someone hits you; it is the poor who are lucky; it is the grieving who shall inherit the earth; it is the wide and smooth road that leads to death; those who find life will lose it.

Maybe the very thing Jesus would do to stop migrant deaths in the desert, or to overhaul America’s broken immigration policies, or to undo the partisan divides that paralyze Washington, is the very thing we cannot imagine.

To imagine what Jesus might do is, perhaps, to travel to the edge of knowledge, to some lonely and untapped outpost of the mind, beyond the stark divides that haunt us, beyond our tired notions of good over evil, of law versus compassion, of amnesty versus deportation, of legal or illegal. It could mean to harness the originality and vision that defines the figure of Jesus and to end up somewhere wholly new.

Above all, that is what the immigration debate needs: Radical vision.

As Jesus said of his disciples, “Seeing they do not perceive, and hearing they do not listen, nor do they understand.”

Perhaps it is the same for us.

Notes:

- According to the 2007 U.S. Religious Landscape Survey by the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life; see religions.pewforum.org.

Ananda Rose Robinson received an MDiv degree from Harvard Divinity School in 2003 and recently completed her Harvard dissertation on the intersection of religion, law, and immigration, in which she focused, in particular, on migrant deaths in the Sonoran Desert.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.