Featured

Ecological Spiritualities and Contemporary Art

By Daniela Cordovil

Over the past decades, a growing concern over global climate change has been reflected in an increasing number of artists and art exhibitions that address ecological matters, while in more recent years, native populations and their knowledge have acquired greater visibility in artworks. The threats that capitalism and climate change pose to native populations is now an important political agenda, and indigenous ways of living and connectedness to the environment are being approached by artists as a source of spiritual knowledge.

In this essay I use quantitative and qualitative methodologies to discuss the thematic presence of ecological spiritualities in artworks found at four art exhibitions: the Documenta 14, held in Kassel in 2017; the 57th Venice Biennale, also held in 2017; the 32nd São Paulo Biennial – Incerteza Viva (Live Uncertainty), held in 2016; and Cosmopolis#2, held in Paris in 2019. Among the most relevant contemporary art exhibitions, the Documenta and Venice Biennale are important barometers for gauging trends in contemporary art. The 32nd São Paulo Biennial is one of the most relevant art exhibitions in Latin America and has a strong presence of artists living and working outside Europe and North America. Cosmopolis#2 is part of a large project at Georges Pompidou Centre in Paris that incorporates art made in Africa, Asia, and America. Ecological themes are the subject of both the São Paulo Biennial and Cosmopolis#2 and address climate change, the anthropocene, and its alternatives.

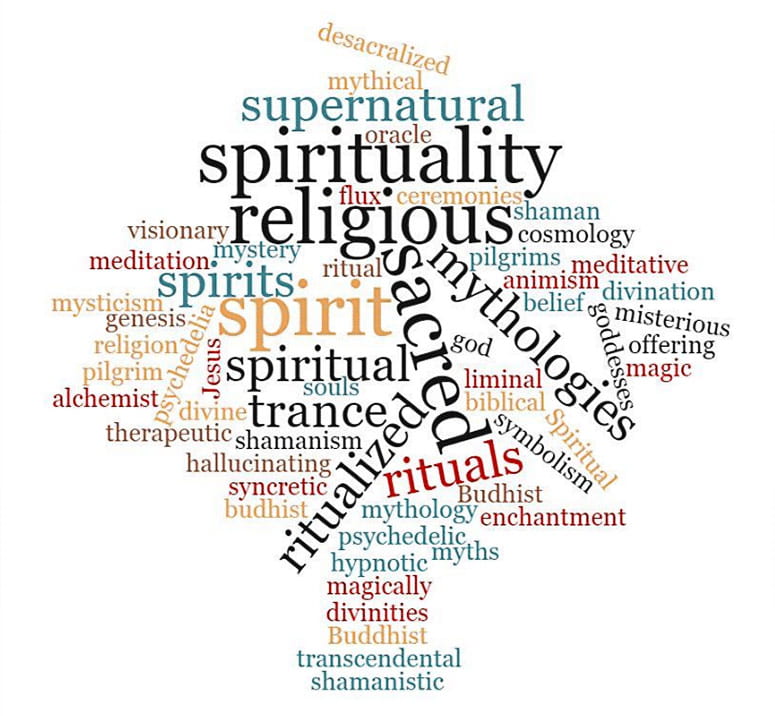

In a search I conducted of words, images, and references to spirituality in the digital catalogues of these art exhibitions, 21% of the 397 artworks appearing in all four exhibitions contained references to spirituality. These results include references to shamanism, paganism, African religions, and eastern religious practices. The word cloud below shows the results of my search of the catalogue of Documenta 14, in which 30 of the 160 artworks exhibited address spirituality.

Word cloud based on search of Documenta 14 online catalogue

Many of these artists are inspired by native cultures from different ecosystems and believe that those cultures have deep connections to spirituality and ways of living that can help protect the Earth and mitigate climate change. I turn next to an overview of some of the exhibited works of five of these artists. Although of different nationalities they have in common the fact that they belong to nations that were victims of violent colonial processes, and they also share an interest in approaching those processes with a critical eye.

The Colombian Mogaje Guihu (born in 1944), whose artistic name is Abel Rodríguez, presented “Annual Cycle of the Floodplain Forest” at Documenta 14. This work consists in botanical illustrations made using watercolor technique and depicting Amazonian flora as it changes over the course of the year. Most are illustrations of leafy trees of different sizes and in many shades of blue and green. Botanical species are presented in precise details, making it possible to recognize their main characteristics.

Rodríguez belongs to the Nonuya people from Colombian Amazon. He considers himself a specialist in the Amazonian flora rather than a professional artist. The technique of watercolor illustration was widely used by naturalists in the 18th and 19th centuries, as a way of recording native fauna and flora of Africa, Asia, and America. Rodríguez’s work has an element of irony and resistance in his appropriation of a technique introduced by colonizers to portray and preserve his own knowledge.1

The text of Documenta 14’s virtual catalog summarizes the curator’s intention in exhibiting this work and notes a ritual connection to native knowledge of plants:

Abel’s precise, botanical illustrations are drawn from memory and knowledges acquired by oral traditions: they are the visions of someone who sees the potential of plants as food, material for dwellings and clothing, and for use in sacred rites.2

This interest in native knowledge of plants, traditional practices, and their spiritual dimensions is present in other artwork appearing at Documenta, including that of artist Aboubakar Fofana.

Fofana was born in Mali in 1967 and left Africa at a young age to live in Paris. He began his career with a focus on calligraphy, reflecting on the relationship between writing and African oral traditions. While traveling through West Africa, he became aware of the tradition of preparing indigo from a plant whose green leaves, when squeezed, release a dye that produces a specific shade of blue. This practice had disappeared in Africa by the time he began his research, and so he obtained much of his information on the process from books and documents found in French libraries.3

In his artwork Fofana uses an indigo manufacturing tank that he set up, in dialogue with local communities, to recreate the traditional indigo fermentation process, without the use of chemical additives. The work “Fundi (Uprising),” exhibited at Documenta, consists of strips of fabric hanging from the ceiling, dyed in different shades of indigo obtained through these artisanal processes. On the floor, some vases with indigo plants are arranged in an L shape.4

According to Documenta’s educational booklet,

The processes Aboubakar employs in his art reflect a profound respect for nature and spirituality. In cooperation with village groups of men and women who still practice traditional handcrafting skills, he produces hand-spun and woven fabrics, which are then dyed in a series of patiently performed procedures.5

Fofana’s artworks suggest that art can aesthetically recreate traditional ways of life, through partnership and dialogue between artists and local communities. A fundamental idea in Fofana’s work is the belief, learned from traditional peoples, that nature is sacred; by learning traditional practices, and using natural products, artists can put the public in contact with this sacredness.6

The Canadian artist Beau Dick (1955–2017) was a Kwakwaka’wakw chief. His art consists in sacred wooden masks made by the traditional techniques of his indigenous people, the Kwakiutl, for Potlatch rituals—traditional gift-giving ceremonies in which indigenous chiefs offer each other goods, in a kind of competition to offer products in ever greater quantities. Two collections, each containing 22 masks, were displayed in Documenta. The masks are made of wood with the addition of various materials such as rubber, acrylic paint, and horsehair. Many are decorated with zoomorphic shapes, a characteristic of the handicraft of several indigenous peoples. The zoomorphic characteristic of the masks represents, in indigenous cultures, the possibility of interchange between humans and nature, since, in these societies, there is no rigid separation between humans and animal, and animals and plants have their own language and culture in indigenous mythologies.7

The Documenta’s online catalog notes the ritual function of these masks:

In Dick’s hands, masks are not simply masks, they are animate beings that have important roles outside the confines of contemporary art. He is continually short-circuiting their status as a commodity. In 2012, he removed the forty Atlakim (Forest) masks from the walls of his gallery and brought them back to his community in Alert Bay, where they were danced for a final time and then ceremonially burned. There is rebirth within this destruction, as now there is a responsibility to carve a new set of masks, which in turn keeps them alive.8

Beau Dick’s artistic trajectory is like that of the artists discussed above. He was born in a traditional population, left his country at the age of six and developed his career in western art using traditional knowledge and techniques learned from his people. As with Rodríguez and Fofana, Beau Dick’s artwork proposes a return to artisanal manufacturing processes, obtained through learning with local communities. The works of these three artists narrate similar stories of native populations oppressed by colonial powers, struggling to keep their traditions alive. Among these traditions are myths, cosmologies and spiritualities characterized by animism, the practice of attributing human characteristics to nature. These artists place themselves as mediators between western and traditional indigenous cultures. They do not see themselves as individual authors, because they create based on collective knowledge, and so they move away from the romantic idea that exceptional artwork must be conceived by individual genius.

In 2017, the 52nd Venice Art Biennale had as its theme “Life, Art, Life,” artistic creation in its relationship with everyday life. This theme approaches art as a practice, valuing the ways in which artists understands their work and place in the world, while at the same time emphasizing the artistic ability to bring magic and enchantment to the world through art. The exhibition was organized in thematic pavilions. Two Brazilian artists, Ernesto Neto and Ayrson Heráclito, presented their work in the Shaman Pavilion.

Ernesto Neto (born in 1964) began his artistic career in Rio de Janeiro in the 1980s. In 2013, Neto met the Huni Kuin indigenous people on a visit to their traditional territory and began to participate in rituals with ayahuasca in Rio de Janeiro. Neto’s artworks use geometric patterns inspired by indigenous graphics whose sensorial universe refers to tactile, visual, and olfactory experimentation.9 For the artwork he presented in the Shaman Pavilion, entitled “A Sacred Place,” he invited shamans from the Huni Kuin indigenous people to perform a ritual inside a sculpture that he created using ayahuasca, a traditional drink made using Amazonian plants that has hallucinogenic effects.

During this performance, the shamans ritually distribute ayahuasca to the public. They explain the meaning of ayahuasca and the ritual, called “Jiboia dance,” some speaking in their native language, which is translated into Portuguese by an interpreter for Ernesto Neto, who then translates it into English. For the Huni Kuin, this ritual is related to their myths on the origin of the world. Neto compares the Jiboia dance and its symbolism with the myth of Adam and Eve to make himself understood by those present.10

Born in the Brazilian city of Macaúbas, Ayrson Heráclito (born in 1968) lives and works in Salvador, Brazil. His artwork appearing at the Venice Biennale and entitled “O Sacudimento da casa da Torre” (The Shacking of Casa da Torre) is a performance of a ritual originating from the healing practices of Afro-Brazilian religions and from African resistance to slavery. In an interview Heráclito refers to this performance as one of the most important works of his life that took more than ten years to complete, as it required special spiritual and financial preparation. Heráclito and the other participants in the performance are priests initiated in Candomblé, an Afro-Brazilian religion. The work is made up of two panels placed one in front of the other, upon which are shown videos of two performances, one in Brazil and the other in Africa. Large photographs of these performances are also displayed in the hall.

Heráclito describes this artwork as a “cleaning” in two historic spaces related to slavery on both sides of the Atlantic: the one in Bahia, is the Garcia D’Ávila Castle, which belonged to one of the richest and most authoritarian slaveholders in America, who was also responsible for a genocide of Native American peoples; the other is the House of Slaves, located on the island of Goreé, in Senegal. This cleaning ritual, Heráclito explains, is a kind of exorcism to remove bad fluids, what he describes as “cleaning the house with sacred leaves.” The plants used to remove evil spirits are “hot” leaves, as they are associated with Afro-Brazilian deities responsible for heat. They serve to drive away Egun, the cold energy of the dead. According to Heráclito, the intention of the ritual is not to purify the spirit of dead slaves but is, instead, directed against the spirit of slave owners. The rite aims to quell the energy of the colonial processes remaining in the world, especially that of slavery.11

The political and mystical character of Heráclito’s work has in common with Neto’s “Jiboia dance” the use of a performance to make a postcolonial critique, a denunciation of ancient and contemporary processes of social oppression. In both performances there is no separation between performance and ritual, with its magical-religious effectiveness. These artists believe that their art can promote changes in the world, through reflections and political attitudes, combined with mystical skills.

The artworks discussed above use masks, paintings, drawings, manufacturing techniques, performances, and rituals to dialogue with a number of indigenous cultures that have been marginalized by Western knowledge and economy. The artists draw on traditional knowledges and ways of life to create products and processes that develop traditional techniques used by native cultures to build emotional bonds with those groups. In so doing, they display a creative process that both learns from non-capitalist and artisanal ways of life, and values alternative ways of relating to nature and traditional processes of transmitting knowledge. By drawing attention to a multiplicity of paradigms and possible worldviews these artworks encourage a rethinking of the relationship between humans and nature and between spirituality and ecology. They harbor critiques of the indiscriminate advancement of capitalism and its resulting depersonalization of work-relations and the dissolution of community ties, as well as critiques of the colonial expropriating of colonized cultures and environments that sustain the capitalist system.

Notes:

- Documenta 14 Laufmappe, https://www.documenta14.de/en/public-education/25631/laufmappe.

- José Roca, “Abel Rodríguez,” Documenta 14 (2017), https://www.documenta14.de/en/artists/13538/abel-rodrigue.

- Johanna Macnaugtan, “Aboubakar Fofana,” Documenta 14 (2017), https://www.documenta14.de/en/artists/13516/aboubakar-fofana.

- Aboubakar Fofana, “Funding (Uprinsing),” Documenta 14 (2017), https://www.documenta14.de/en/artists/13516/aboubakar-fofana.

- Documenta 14 Laufmappe, https://www.documenta14.de/en/public-education/25631/laufmappe.

- Macnaugtan, “Aboubakar Fofana,” Documenta 14 (2017), https://www.documenta14.de/en/artists/13516/aboubakar-fofana.

- Documenta 14 Laufmappe, https://www.documenta14.de/en/public-education/25631/laufmappe.

- Candice Hopkins, “Beau Dick,” Documenta 14 (2o17), https://www.documenta14.de/en/artists/13689/beau-dick.

- Ilana Goldstein and Beatriz Caiuby Labate, “Encontros Artísticos e Ayahuasqueiros: Reflexões Sobre a Colaboração Entre Ernesto Neto e Os Huni Kuin,” MANA 23, no. 3 (2017): 437–71, at 449.

- A 45-minutes video with part of the ritual is available at: Ernesto Neto, “Biennale Arte 2017 – Ernesto Neto (Performance),” Biennale Chanel, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VsHWj5IdA2E.

- Régis Gonçalves, “Ayrson Heráclito in Conversation with Régis Gonçalves & Contemporary Art,” YouTube, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X44NTFL1y58.

Daniela Cordovil is Assistant Professor at Pará State University (Brazil). She has a PhD in Social Anthropology by University of Brasília (Brazil).

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.