Featured

Her Sister’s Blouse

Contemporary Jewish museums are sites of memory and community.

Remnants, Sydney Jewish Museum, 2017. Courtesy Sydney Jewish Museum

By Avril Alba

The extraordinary boom in the development of Jewish and Holocaust museums in the late twentieth and early twenty-first century requires a consideration of the role these institutions play in creating and conveying Jewish collective memory. How and why a people traditionally focused on the written word developed a plethora of institutions that rely upon visual mediums remains largely unexplored. Have these institutions, in asserting the primacy of the image and the object in conveying the Jewish past, ushered in new forms of Jewish memory? Do these spaces provide an alternative, or at least a supplement, to traditional text- and ritual-based forms of commemoration and, if so, how have they contributed to and transformed the transmission of individual and communal memory for a people for whom the image has long been an object of suspicion rather than veneration?

Indeed, can they even be understood as Jewish spaces? Certainly, not all Holocaust museums consider themselves to be preserving Jewish memory, while many Jewish museums do not consider Holocaust education and commemoration to be within their core remit. Further, the most well-known and monumental of these institutions are generally the result of either public or public and private partnerships intimately connected to state imperatives. Examples include now iconic structures such as the Jewish Museum, Berlin, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, DC, and Yad Vashem, Jerusalem. As James Young has so compellingly argued, these spaces have been deeply influenced by the national contexts in which they were formed.1 Yet, as my own work and that of others has demonstrated, even state-funded Holocaust museums and memorials draw upon and transform traditional Jewish paradigms in their commemorations and displays.2 To focus on the meaning and transformation of Jewish memory in these places is therefore not to suggest they aim to replicate normative religious practice or provide evidence of a systematic theology. Given that these institutions are situated at the intersection of the Jewish and broader communities, such conclusions are neither possible nor useful. But for those museums that were initiated and built with input from Jewish individuals and communities, it is arguable that the role these institutions play in preserving and creating Jewish memory is yet to be fully explored.

This lack of understanding exists despite the fact that the relationship between museums, heritage, and identity has long been acknowledged.3 For example, national museums are often referenced as key sites of identity formation, locations through which narratives of the nation are produced and consumed. Rather than the museum being seen as a site where national identity is simply inculcated, such research argues for a nuanced understanding of the role of the visitor, noting the active, affective experience of visitors who make and remake the museum according to their own needs and understandings. In such a paradigm, museums are seen as “contact zones” where such contact is “lived, negotiated and contested.”4 Scholars and museum practitioners are increasingly interested in how community museums can also provide “local contact zones” where individual and communal identity meet in a mutually productive and transformative encounter—a space in which community identity is developed, conveyed, and ultimately transformed.

The move from a text-based form of collective memory to one based in images and objects demands a consideration of how these institutions influence and contribute to the shape of Jewish memory, as well as contributing to the life of Jewish communities today.

As its first mission statement proclaimed, the Sydney Jewish Museum (SJM) is a “museum about a people.”6 The SJM was named to reflect its mission to represent the history and experience of the Jewish people in its totality. Officially opened in 1992, the museum was founded and funded by philanthropist and Holocaust survivor the late John Saunders AO, in partnership with the Australian Association of Jewish Holocaust Survivors (AAJHS). The museum is housed within the Maccabean Hall, opened by General Sir John Monash in 1923. The hall served to commemorate Jewish soldiers who lost their lives in World War I but soon became a vibrant center of Jewish communal and cultural life, where meetings, debates, dances, and religious services took place. In 1965, the Maccabean Hall became the NSW Jewish War Memorial Community Centre, and in 1992 it was transformed yet again into its current incarnation as the Sydney Jewish Museum.

While the museum’s vision is to embrace the entirety of Jewish history and expression, its founders were drawn largely from Sydney’s survivor community. The Australian Jewish community was profoundly changed by the survivor generation whose numbers more than doubled what had previously been a largely Anglo and Anglophile, as well as numerically insignificant, community. The survivors’ dedication to communal concerns shaped all aspects of Australian Jewish life in the second half of the twentieth century.

Coming to Australia as refugees—more often than not sole survivors or orphans, speaking little or no English, and often without any professional training or skills—these survivors’ contribution to the Australian Jewish and broader communities is nothing short of astonishing. Carrying nothing but the memories of their destroyed communities and lost loved ones, most survivors yearned for the structure and safety of ordinary everyday life. Communal organizations set up programs for them to gain language and professional skills, but there were few formal training opportunities. It was difficult to establish daily routines, to forge local networks and attain modest material comforts in their new surroundings. Achieving these milestones signified the beginning of the long road back to a semblance of normal existence. With sheer determination, most succeeded in creating new and fulfilling lives. For many survivors, completing even minor transactions of everyday life in their new language was a proud moment. It was also a significant step since language skills opened a pathway into their new society and increased their possibilities for education and employment.

Despite these difficulties and often facing official and popular discrimination, survivors focused on rebuilding family and community life, reinvigorating the established Australian Jewish community, and contributing to broader Australian society. Many had been deeply involved in European cultural and political pursuits before the war and reignited these interests in their new surroundings. These personal passions had a profound effect on the Australian artistic and intellectual landscape. Yet those lacking recognized qualifications were often unable to practice their former occupations. As a result, they worked long and hard in menial and unfamiliar jobs. For many women, a sewing machine dominated their small home. Men often started at the bottom of the employment ladder as cleaners, factory workers, or drivers, often becoming independent entrepreneurs. Business partnerships were established among fellow survivors dealing in textiles, clothing, furniture, property development, leather goods, small goods, entertainment, and hospitality. Some embarked on academic or artistic careers while others opened delicatessens, cafés, and restaurants that changed the culinary landscape of Australia forever.

The survivors also invigorated and transformed the Australian Jewish community. Assisted by funds from overseas Jewish organizations and German reparations, they were motivated to regenerate aspects of European Jewish life in their new homeland. They developed cultural, social, and sporting societies that diversified their own communal life and benefited the wider community. They also contributed significantly to the revival of the Jewish day school movement. With the birth of the state of Israel, and the support of the new migrants, the Zionist movement shifted from the fringe of the community to its center.

Yet, along with their strong desire to rebuild and renew, survivors also carried traumatic memories and the irreparable loss of family and friends. In their preoccupation with the demands of creating a new life, many suppressed these memories for decades, yet their pain never completely left them. For some, the objects they were able to save represented these wounds. These objects, salvaged from their Holocaust experiences, in some cases enabled their very survival. Others represented lost relatives and communities, poignant reminders of life prior to the war. Imbued with layers of meaning over the course of time, they have come to embody trauma and loss, resilience and continuity. Together, they provide an intricate and textured portrait of a generation that has left an indelible mark on the Jewish and broader Australian community.

These humble objects speak as well to the ongoing effects of the survivors’ experiences, each the embodiment of an individual attempt to make sense of life against a backdrop of loss. They also allow us to understand the continuing effects of this loss as the object is inherited and reinterpreted by descendants—children and grandchildren. As succeeding generations seek to recover and understand the gaps in their family’s histories, these objects bear witness to intergenerational rupture and rebirth, providing a window into a world no longer extant, while concurrently illustrating the influence of that world on contemporary realities and experiences.

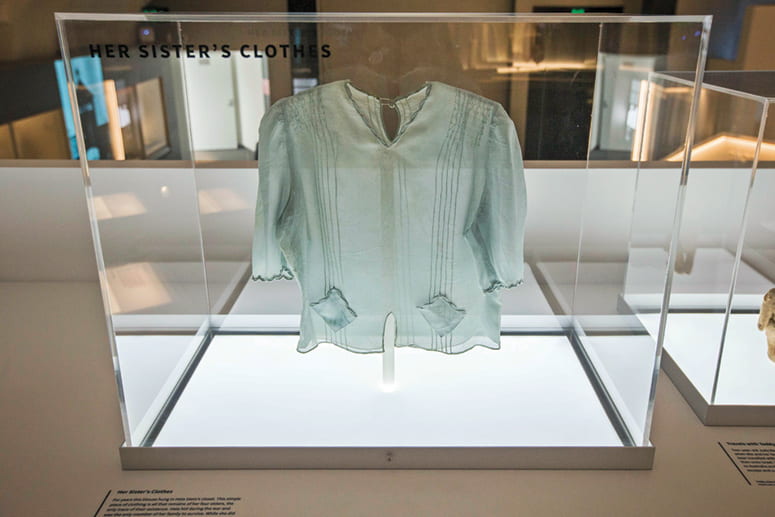

Blouse, Warsaw, date unknown. Donor Mary Ziegler (Daughter), Sydney Jewish Museum M2012/011. Courtesy Sydney Jewish Museum

For the late Hela Stein, a simple blouse bore witness to her Holocaust past. The blouse is the only material evidence left of her four sisters’ lives. Opening the closet doors where she had placed the item, Hela would look at the blouse and remember her younger siblings. She never wore it, simply opening the closet door every now and then to stare at it and then close the door again without saying a word. Hela hid during the war and was the only member of her immediate family to survive. The blouse was the one object that connected her to her family and her life before the war. One day her daughter Mary finally asked her mother what significance the blouse held. Her mother answered that it was the sole item she had left from one of her four sisters, all of whom had been murdered.

For Mary, the meaning and memories embodied in the blouse multiplied throughout her own life. When asked at what point she realized its importance as the singular witness to her family’s history, she regretfully noted that it was only upon her mother’s death that the true significance of the object became apparent: “I realised I did not know how she [Hela] had obtained it. Why didn’t I ask? Why didn’t I think to do so? Perhaps because I knew I wouldn’t be answered?” Mary recounts feeling a deep sense of historical loss upon her mother’s death, a loss of connection to a world she did not know but that her mother had unconsciously embodied. While she could not articulate exactly why she felt so strongly at the time, Mary noted that “there was no question that the blouse would come home with me.” The blouse hung in Mary’s closet for nearly 20 years, at which point she decided to donate it to the Sydney Jewish Museum.

“I think the reason I gave it to the museum is partly due to one of the children I took on a [museum] tour a few years ago. I told them about the only item my father retained from the war—a watch—and how my father found it and now we have it. And one bright spark put up his hand and said, “Excuse me, you know the watch, who are you going to give it to?” And I thought—that is a very good question! Who am I going to give this to? Who? And it made me think about the blouse and that maybe the museum would be interested in it because it is an historical piece. But it’s also a piece that shows that this history does not end.”

Indeed, the history continues with Mary’s own relationship to the blouse and her mother’s experiences. “As I get older and more emotional there are more and more questions: Why don’t I know, why can’t I remember? Did she tell me and if she did, why can’t I recall? I ask myself: which sister? They were all small at the time of the war but it’s clearly too big for the little ones. Who made it? Was it made or bought? These are small things, but they tell a bigger story . . . I want to know if it was special, I want to know if it was an everyday thing. I look at the detail and I have to believe it was a special occasion blouse. But on what occasions did they wear it? I want to know how she came to have it, I want to know exactly which sister it belonged to, and I want to know how it was used. Just these basic things and there is no way. . . .”

When questioned on what she hopes the museum visitor will take away from an encounter with the object Mary pauses: “I wonder, I wonder . . . maybe that it is more than just a personal thing. That it tells a story, an important story. I do wonder . . . do they look at it closely? Do they actually come up close to look at it and have a look at the finer detail of it? And think, oh, who did this belong to, how old was she and what happened to her? Do they think of the intensity of the loss? That this little blouse belonged to someone who had a future . . . that this little blouse was obviously a . . . a fine thing. Someone who owned it would have seen it as a fine piece of clothing and what could this little someone have become?”

For Mary, the item encapsulated both her mother’s losses and her own relationship to her mother’s trauma. A container of intergenerational memory in both psychic and physical senses, the blouse had come to symbolize those aspects of the Holocaust experience that could not be healed and that would by necessity be carried and conveyed to new countries, families, and communities. This simple item of clothing became a conduit to her mother’s family and a vital if tenuous link to a world she would never fully know or understand. It was also a means by which she came to appreciate more fully her mother’s losses and the effect of those losses on herself and her own children.

This simple blouse also gestured toward the resilience of the survivor generation and the complexity of their legacy—a legacy with which their descendants continue to struggle.

What is the function of such objects, such spaces, if not to create powerful and dynamic communities of memory? Through their layers of meaning, these objects reverberate well beyond their historical point of origin. They defy outdated notions of museums as places only of the past and give voice to the vital role that they play in identity formation in the present. They speak of and to individuals, families, and communities and bring us into connection with a Jewish civilization that we often refer to as lost, but whose influence resonates well into the present. Humble objects such as the blouse, in concert with the myriad photos, films, and documents that Jewish and Holocaust museums internationally continue to collect and preserve, provide an imperfect but vital conduit to pre-war Jewish life, allowing us to reach back across the breach and to reclaim, albeit partially, the cultural legacy that is our true inheritance. Functioning as a bridge to the past and a canvas for and of the present, the contemporary museum has emerged both as an interpreter of Jewish memory, and equally a site of, and for, Jewish community.

Notes:

- James E.Young, The Texture of Memory: Holocaust Memorials and Meaning (Yale University Press, 1993) and At Memory’s Edge: After-Images of the Holocaust in Contemporary Art and Architecture (Yale University Press, 2000).

- Avril Alba, The Holocaust Memorial Museum: Sacred Secular Space (Palgrave MacMillan, 2015); Oren Baruch Stier, Committed to Memory: Cultural Mediations of the Holocaust (University of Massachusetts Press, 2003); Jennifer Hansen-Glucklich, “Evoking the Sacred: Visual Holocaust Narratives in National Museums,” Journal of Modern Jewish Studies 9, no. 2 (2010): 209–32.

- Elizabeth Crooke, Museums and Community: Ideas, Issues and Challenges (Routledge, 2007).

- Phillip Schorch, “Contact Zones, Third Spaces, and the Act of Interpretation,” Museum and Society 11, no. 1 (2013): 68–81.

- Margaret Olin, The Nation without Art: Examining Modern Discourses on Jewish Art (University of Nebraska Press, 2001).

- The SJM’s mission statement prior to 2003.

- Accession number M2012/011.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.