Dialogue

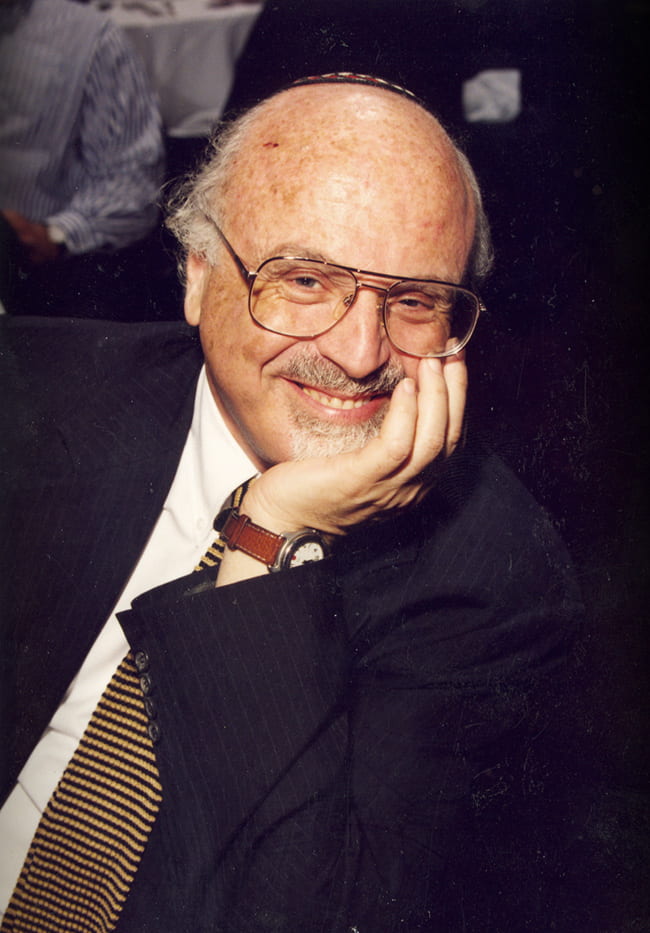

God Talks: Neil Gillman Remembered

Rabbi Neil Gillman pushed his students to think about theology with more rigor and more imagination.

By Daniel Ross Goodman

In Chaim Potok’s autobiographical novel and sequel to The Chosen, titled The Promise, Potok’s alter ego, Reuven Malter, a student at the Hirsch Theological Seminary (modeled on Yeshiva University, the flagship institution of Modern Orthodox Judaism) starts using the library of Frankel Seminary (modeled on the Jewish Theological Seminary, the founding institution of Conservative Judaism in the United States). There, he meets the scholar Abraham Gordon, based on Mordecai Kaplan. Reuven strikes up a friendship with Gordon—as Potok himself had done with Kaplan—and begins to have regular meetings and conversations with him. When Reuven’s rabbis at Hirsch find out, his Talmud instructor threatens him by saying he may not be able to grant him rabbinic ordination if he continues to see Gordon. Reuven, though, does not stop meeting with Gordon and is forced to reckon with the repercussions of his intellectual curiosity.

Shortly after graduating from Yeshiva University, and months before enrolling in Yeshivat Chovevei Torah, an Orthodox rabbinical school, I began visiting the Jewish Theological Seminary (JTS) to use its library. There, I met Rabbi Neil Gillman, a student of the real Mordecai Kaplan, and struck up a friendship with him. We began to have regular meetings and conversations.

“Once you start Chovevei,” Rabbi Gillman asked me, “will you still come to see me?”

“Of course,” I replied.

“They won’t kick you out if they find out? What if they hear, ‘He’s meeting with Gillman?’ ”

“I don’t think it’s that kind of Orthodox school.”1

A big smile came across his face.

“I know it’s kind of like Reuven Malter continuing to go see Abraham Gordon, but Chovevei isn’t Hirsch,” I said.

“ ‘You’re still seeing Gordon?’ ” Rabbi Gillman quoted the novel, still smiling. “They won’t ask you, ‘You’re seeing Gillman?’ ”

“They might ask, but I think they’d be OK with it.”

“Great. Please come back. I hope we can continue this while you’re at Chovevei.”

I was honored—flattered, frankly—that one of the foremost Jewish theologians had taken such an interest in me. It wasn’t only me, though—it was every single one of his students. What made Rabbi Gillman so special, and why so many of his students have been so downcast since his death in late 2017, was the devotion that he—a great scholar and a towering intellect—would bestow on even the least accomplished of his students, and even on those like me who were not officially his students. He encouraged all of us to think seriously and creatively about theology; he was a true Gott-getrunken Mensch, a man intoxicated by God, who believed that we could all become “intoxicated” as well, if only we allowed ourselves to drink.

During many of our conversations, he would ask me, “Why is it that the Orthodox never talk about God?”

“I don’t know,” I would respond, “but I think we should be talking about him.”2

We disagreed about many things—including what my pronoun of choice for God and my traditionalist theology portended for my conception of the divine. Even though he didn’t succeed in persuading me to adopt his theology, he succeeded in getting me, an Orthodox Jew, to talk about God—and to devote my rabbinic and graduate studies to theology—much as he succeeded in getting thousands of Jews across all denominational lines to talk about God over the course of his remarkable 50-plus-year career.

When I met Rabbi Gillman a few years after I graduated from college, I had already begun thinking hard about theology, but he pushed me to think about it even harder, with more rigor but also with more imagination. His own life-changing moment, he told me, occurred when he was a college student at McGill. He was a philosophy and French literature major who wasn’t giving too much thought to Judaism at the time. At McGill, he happened to hear Will Herberg speak. Herberg—one of the great but overlooked twentieth-century scholars in his field, he said—sparked a shift in his thinking about Judaism and Jewish philosophy.

“Here was a person of great sophistication,” Rabbi Gillman told me, “a great intellect, who was taking Judaism seriously, who was saying that Judaism addresses some of the most important questions of our time and of all times.” If such a man could take Judaism seriously, he said, “Then shouldn’t I?” After graduating from McGill, Rabbi Gillman kept his word, turning down a fellowship to study philosophy at Princeton and enrolling instead as a rabbinical student at the Jewish Theological Seminary, affiliated with Conservative Judaism.

Rabbi Gillman arrived at JTS at a time when two of the greatest Jewish theologians of the twentieth century, Mordecai Kaplan and Abraham Joshua Heschel, were still teaching at the seminary. Rival schools had formed around the two esteemed sages—a veritable latter-day Beit Shammai (House of Shammai) and Beit Hillel—and Rabbi Gillman became quickly ensconced within Beit Kaplan, convinced that Kaplan was a real philosopher while Heschel, in his view, was “merely” a poet.

Although he was a Kaplan devotee, he could never completely give himself over to Kaplan’s philosophy of Judaism,3 and he certainly couldn’t bring himself to join Reconstructionism, the new denomination that was being created based upon Kaplan’s teachings—in part because Rabbi Gillman was opposed to the liturgical changes that Kaplan wished to make and to the new rituals that Kaplan wanted to institute, which Rabbi Gillman found too radical.4 Though he was attracted by Kaplan’s theological boldness, he believed, unlike Kaplan, that core Jewish practices—keeping the Sabbath, eating kosher, praying with essentially the same liturgy—should be preserved. He would later go on to become one of Conservative Judaism’s most important thinkers, writing perhaps the definitive statement of the movement’s philosophy in his 1993 book, Conservative Judaism: The New Century.

Soon after receiving his ordination, Rabbi Gillman began teaching at JTS while simultaneously pursuing a doctorate in philosophy at Columbia University. He saw that nobody was really covering Conservative Jewish theology, he told me, so he set out to do exactly that. Based on the ideas of Paul Tillich and Paul Ricoeur—his two foremost influences in the worlds of non-Jewish theology and philosophy—he came up with the idea of the “myth of Sinai.” (When he was at JTS, he said, nobody really believed that the Torah—the Five Books of Moses—was literally given by God to Moses at Sinai, but they didn’t admit it yet.) By “myth” he did not mean something that was “false”: he crusaded against the misuse of the term “myth” as “falsehood,” even writing letters to the editor of The New York Times when writers conflated these non-similar terms by publishing columns bearing titles such as “The Myths and Facts of the Republican Tax Plan” (which invidiously implies that “myths”=“lies”).

Instead, he used the term “myth” to mean an organizing principle into which we fit certain facts and experiences, a narrative structure that communicates a community’s master-narrative. Myths, he wrote, are “sublime metaphors, poetic constructs that capture dimensions of reality beyond normal experience.” They “inspire us to act in certain ways and strive for certain goals, and most important, lend infinite meaning to our lives in the here and now.”5 The idea that the Torah was given at Sinai, he asserted, is a myth that helps us conceptualize our lives as Jews; thinking about our sacred scriptures as all having originated in a certain place at a certain time lends coherence to our religious lives and creates an important sense of unity and order—a sacred framework—through which we can understand our voluminously diverse inherited traditions and our confusing, chaotic world.

Rabbi Gillman’s book Sacred Fragments—controversial and downright heretical for traditionalists, refreshing and soul-saving for progressives—is undoubtedly his greatest theological legacy. Yet, consistent with his view of himself as a teacher above all else, he stated that he wished his legacy to be his teaching on Paul Tillich’s statement on the meaning of symbol in Dynamics of Faith,6 a passage Rabbi Gillman would use when teaching that one can remain rooted in faith even when literalism ceases to be an intellectually viable option.7

By the time I met him, Rabbi Gillman’s attitudes toward Kaplan and Heschel had shifted somewhat; he was the kind of scrupulous but undogmatic thinker who was unafraid to change his opinion on an issue when confronted with new evidence or more enlightened understandings. His readings in neuroscience led him to admit that he had been unfair to Heschel, who was doing something unheard of at the time: theological poetry, which is right-brained, creative, and associative—rather than religious philosophy, which is left-brained, scientific, and logically rigorous. (That theology could be done through an artistic rather than a scientific discipline also captured my attention and was one of the principal factors that convinced me to study literature rather than philosophy at Columbia, in the hope of one day being able to pursue theology through literature—a path rarely taken in Jewish theology, but a path which offers some of the richest, most imaginative possibilities for the future of Jewish theology.)

Conversely, Rabbi Gillman had come to believe that Kaplan had failed a major test as a theologian in that he had not dealt with the problem of suffering and evil, something very few have done in Jewish theology in general. There is an abundance of material on suffering in rabbinic literature—in the Talmud and in the midrashim—as well as in the Book of Job, but it is not gathered together and organized in a coherent way, which makes it difficult for Jews to talk about the subject. (Rabbi Gillman bemoaned the fact that many Jews seem much more uncomfortable than Christians with talking about and confronting suffering.) His final book, Believing and Its Tensions: A Personal Conversation about God, Torah, Suffering and Death in Jewish Thought (Jewish Lights, 2013), was an attempt to use the tools of the Talmud to confront suffering. It was indeed a very personal book for Rabbi Gillman; much of it was either written or mentally planned out when he himself was suffering while being treated for cancer.

In his later years, the subject that came to preoccupy him most was the relationship between neuroscience and religion. When I asked him why he was reading Eric Kandel, Antonio Damasio, and Michael Gazzaniga—three of the world’s most renowned contemporary neuroscientists—he explained that a science professor once said to him that “everything is biology,” and the most important component of biology is neuroscience, because everything comes from the brain and works through the brain, including our religious experiences—and thus, perhaps, even God. Consistent with his newfound conviction that theology must begin to take neuroscience into account, he contributed the preface to Ralph D. Mecklenburger’s Our Religious Brains (Jewish Lights, 2012), a book that examines religious belief through the prism of cognitive science.

After my rabbinic ordination, I came to JTS as a doctoral student in modern Jewish thought out of a desire not just to study theology but—encouraged by Rabbi Gillman, of blessed memory (and by my rebbe at Yeshivat Chovevei Torah Rabbinical School, Rabbi Dr. Yitz Greenberg)—to “do” theology. I wanted to continue to talk theology with Rabbi Gillman at JTS; I wanted to continue our far-ranging, deeply probing conversations about all things God. Alas, like so many others, I am deeply saddened that my God-talks with Rabbi Gillman have come to an end. I sorely wish he were still here. But, irrespective of any of our views on theology, and whatever each of us may or may not believe about the resurrection of the dead and the world to come, Rabbi Gillman always will be—in books (the ones he wrote, and the ones he inspired), in the institutions he loved and shaped, and in God-intoxicated minds across the world, including mine.

Notes:

- Yeshivat Chovevei Torah is a Modern Orthodox rabbinical school that was founded in 1999 as a more open-minded, progressive, inclusive alternative to the Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary (RIETS), Yeshiva University’s rabbinical school, a centrist Orthodox institution which, in the eyes of some, had shifted too far to the right.

- There are Orthodox theologians, such as Rabbi Irving “Yitz” Greenberg, my “rebbe” (rabbi, teacher, and mentor) at Chovevei, who do talk about God, but for the most part, bona fide, intellectually open-minded God-talk in Orthodox Judaism can be hard to come across, most likely due to Orthodoxy’s overriding emphasis on halakhah (ritual law) and its tendency toward rigid dogmatism.

- Mordecai Kaplan (1881–1983), influenced by John Dewey and the school of American pragmatism as well as by Ahad Ha’am (Asher Ginsberg), applied principles from the newly emerging discipline of sociology to Judaism in construing Judaism as a “civilization.” Kaplan, a naturalist (like Spinoza before him), sought to purge Judaism of any remaining vestiges of supernaturalism, maintaining that God is an impersonal force in the universe. Consequently, Kaplan viewed the mitzvot (commandments) of the Torah not as divinely ordained commands but as “folkways” developed organically within Jewish civilization over its long existence.

- Although Rabbi Gillman did not believe that halakhah (Jewish law) was absolutely binding upon each and every Jew, he believed that any Jew could choose to accept certain aspects of Jewish Gesetz (law) as Gebot (commandments). One afternoon, while talking with him in his office, Rabbi Gillman looked at his watch and noticed that it was time for Mincha (the afternoon prayer). “I don’t have to go,” he said to me, getting up from his seat and preparing to make his way to the seminary’s chapel. “But I feel commanded to go.”

- Neil Gillman, Sacred Fragments: Recovering Theology for the Modern Jew (Jewish Publication Society, 1990), 266, 271.

- Paul Tillich, “The Meaning of Symbol”, part 3, “Symbols of Faith,” in Dynamics of Faith (Perennial Classics, 2001; Harper & Row, 1957), 47–52.

- During my talks with him, it seemed fairly clear that Rabbi Gillman did not believe that the revelation at Sinai had actually happened, at least not in the way the Torah describes it as having happened. But his construal of Sinai as “myth” was a way of saying that its historicity is irrelevant; what matters is whether you accept the story as one which lends your life meaning.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.