In Review

Giorgio Agamben, the Church, and Me

By Charles M. Stang

Twice in my life I have discerned a call to ordained ministry in the Episcopal Church. The first time was in my mid-20s, just as I had finished my MDiv at the University of Chicago and was beginning doctoral studies at Harvard Divinity School. As if caught in the flow of a swift river, I was carried along by the enthusiasm of the church community where I had served as a seminarian for two years. Their faith in me as a priest carried me downriver, past my own many doubts. In the end, my education was an easy way out, an eddy where I could gracefully step out of the river’s flow: I couldn’t sustain the demands of the discernment process in Chicago while I was beginning my studies anew in Cambridge. If the call were real, I thought, it would return.

And it did, in 2012, near the end of a year-long sabbatical I spent in Jerusalem with my wife and two daughters. But neither did this second call end with my ordination to the priesthood. Almost three years ago, in the summer of 2018, I again bowed out of the process, in which I had advanced beyond “discernment” to what is called “postulancy.” It wasn’t as easy an exit the second time. I had devoted an enormous amount of time, effort, and—dare I say it—prayer to discerning this call. So, too, had many others, and I felt as if I had perhaps squandered their time, and mine—six years. I had no doubt then, and I still don’t, that in stepping away I made the right decision, or, to use the language that is more common in this process, that I faithfully discerned the call. But the truth is that I stepped away from more than just the priesthood: I took a long step back from the church, and not just the Episcopal Church, but “The Church.” What I am left pondering, then, is what it means to say that I faithfully stepped away from the faith.

This has led me to think long and hard about that year I spent in Jerusalem, and why, upon my return, I felt compelled to announce to the bishop of Massachusetts, who happened to be a friend, that I had heard the call anew. What is perhaps most surprising is that during that year in Jerusalem, I almost never went to church. Of course, I was in and out of churches all the time—I particularly love the beautiful chaos and cacophony that is the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in the Old City. But I avoided services of any kind. When I did go to church, to accompany my wife to St. George’s Cathedral on Easter morning, I experienced in the middle of a hymn something like an existential allergy attack: a deep discomfort, almost a panic, and a clear, strong signal that I should run out of the building. I walked, so as not to make a scene. But when I got outside into the courtyard on that beautiful spring morning, I felt as if I could once again breathe. How is it that one can experience something like that and still feel that one might be called to be a priest? How could I be called to be priest if I had an allergy to church?

It may come as a surprise that part of the answer lies in a small book by the Italian philosopher and political theorist Giorgio Agamben. The book in question is The Church and the Kingdom: it is the transcript of an address—what his translator insists was more of a homily—Agamben delivered on March 8, 2009, in Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris, to a distinguished audience of church officials, including the bishop of Paris, André Vingt-Trois. Agamben is famous, among other things, for his 20-year, nine-volume series Homo Sacer, which title derives from the inaugural 1995 volume, Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life. The complete series was recently published by Stanford University Press as The Omnibus Homo Sacer. I was first drawn into Agamben’s orbit during that year in Jerusalem, when a friend insisted that I read what was then the latest volume, The Kingdom and the Glory. I had heard of Agamben, and other friends had already recommended him, but the sabbatical allowed me to pause long enough to read him. I read widely in the Homo Sacer series, and in adjacent works, but I do not claim, or aspire to claim, expertise in Agamben’s thought. But however much I read, I kept coming back to his small book, The Church and the Kingdom, because in it Agamben succinctly put into words an inchoate suspicion I had long harbored about Jesus’s preaching about what he called the “kingdom,” and the ambivalent place of the “church” that came in its stead. To be more precise, Agamben argues that the heart of the gospel, and the coming of the Messiah, is about our relationship to time.

The title of Agamben’s book deliberately recalls a much earlier work, Alfred Loisy’s 1902 book, The Gospel and the Church.1 Loisy, who was a French Roman Catholic priest, is most (in)famous for the quip, “Jesus foretold the kingdom, and it was the Church that came,” which Agamben paraphrases, attributed to an anonymous “French theologian.”2 But what did Loisy mean by this quip? Perhaps surprising to our ears, it was not meant to be critical of the church. Reacting to Adolf von Harnack’s über-Protestant critique of the church, Loisy was aiming both to account for the continuity between Jesus’s proclamation of the kingdom and the establishment of the church and to acknowledge the change that attended that continuity. Relying very much on John Henry Newman’s notion of doctrinal “development” (from his 1845 Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine), Loisy argued that the kingdom is to the church what the acorn is to the full-grown tree. In other words, for Loisy, the church is the natural unfolding of Jesus’s ministry and his proclamation of the kingdom. And as the natural unfolding of that proclamation, the church is also uniquely responsible for preparing the way for the kingdom’s eventual arrival. This is captured in the line, much less quoted than the above quip, from his 1903 Autour d’un petit livre, “The gospel and the Church are in identical relation to the kingdom: they prepare immediately for it.”3

But Agamben reads Loisy differently, as if he had said “but” rather than “and” in his famous quip: “Jesus foretold the kingdom, but it was the Church that came.” To Agamben’s ears, what he calls Loisy’s “bitter irony” is all too clear: much to Jesus’s surprise and disappointment, the church is that which stands in for, and in so doing stands in the way of, the messianic kingdom. The Church and the Kingdom distills to a single question: will the church “recover its messianic vocation?”4 But what exactly is it that Agamben is calling the church to recover? What is the “messianic vocation” on which the church has allegedly turned its back? To return to the telling line from Autour d’un petit livre quoted above, Agamben’s provocation consists largely in saying that in truth the indicative is at best a subjunctive: the church is not, but should be, relating to the kingdom so as to prepare for it, to welcome it.

Agamben invites us to wonder whether or not the church ever arrived but insists that, even so, it has since departed.

As many of Agamben’s arguments do, this hinges on a distinction in Greek, and a distinction in temporality, or how we experience time. The church is supposed to dwell on earth as an exile or a sojourner—captured in the Greek verb paroikein, as in ho chronos tês paroikias, or “the time of sojourning” of 1 Peter 1:17. This sort of sojourning is the proper stance in which to welcome the coming (parousia) of Christ, the Messiah. But from its properly “parochial” (from paroikia) stance, the church has settled into a different dwelling, that of a citizen of a city, state, kingdom, or empire—captured in the Greek verb katoikein. Katoikia is the temporality of institutions and civilizations that put a premium on perpetuity: “we are here to last.” The “bitter irony” is that sojourning, or paroikia, should be the one and only vocation of the church: “It is only in this time [of paroikia and parousia, the sojourn of the foreigner and the coming of the Messiah] that there is a Church at all.”5 Strictly speaking, then, as soon as the church has settled into katoikia, it ceases to be the church, although it may continue to go by that name. If, as Loisy put it, “what arrived was the Church,” Agamben invites us to wonder whether or not the church ever arrived but insists that, even so, it has since departed. The question he puts to the “church,” then, is whether it will recover its vocation as the church. The disquieting but strangely pious provocation Agamben poses to the bishop of Paris is whether the “church” will ever become the church, whether the church will ever arrive, or rather return.

The call for the church to recover its messianic vocation, then, was a call to help it shift its temporality, to sojourn where it had chosen to dwell, to help the church once again heed its own calling, or perhaps to heed it for the first time. If the parousia of the Messiah is available to us only if we change our relationship to time, I thought, then perhaps the priesthood could be understood as a ministry of time, obedience to a different temporality. Perhaps the call to ordained ministry was a call to help the “church” become the church, to help transform it from the inside, to be a priest of the tent rather than the temple, in something like an insurgent ecclesiology, in which the resistance and transformation would revolve around our relationship to time.

Intrigued by this provocation, I read more widely, and deeply, and discovered that this insurgent ecclesiology was tethered to a bleak political diagnosis. Agamben’s ambivalence toward the church is mirrored in his ambivalence to the kingdom. “Church” and “kingdom” each have two divergent referents. On the one hand, the messianic kingdom is that which Jesus proclaimed—not, according to Agamben, as if it were some future event frustratingly deferred, but rather the latent possibility of an inbreaking in every moment. Walter Benjamin is his muse here, who wrote of such a realizable (perhaps also realized) eschatology, “every day, every instant, is the small gate through which the messiah enters.”6 On the other hand, in another of Agamben’s works, The Kingdom and the Glory, the kingdom does not name this messianic moment, but rather one half of the monstrous, modern machine of government. Like many, Agamben has a very bleak view of contemporary world politics. We are all caught in a “providential machine,” whose underbelly is a “global civil war” well underway in much of the world. This machine is constituted by a global, sovereign center, what Agamben here calls the “Kingdom,” surrounded by a “Government” of enforcers. The distinction between “kingdom” and “government” is captured by what the twentieth-century political philosopher Carl Schmitt calls the “notorious formula”: le roi regne, mais il ne gouverne pas, “The King reigns but does not govern.”7 In other words, the sovereign center exists precisely so as to be a vacuum, a void or “empty throne” that requires encircling phalanxes of governors, bureaucrats, messengers, and enforcers to mask its fundamental impotence. These exist not only to govern the masses but to glorify the hole at the center of it all. Agamben sees contemporary politics as essentially an endless and acephalous administration.

There is something vaguely compelling about this political diagnosis, but it was never what most intrigued me about Agamben. The originality of The Kingdom and the Glory consists not in this diagnosis (which is very much derivative of Michel Foucault), but in his claim that the modern rupture between “kingdom” and “government” can be traced back to classical Trinitarian theology. For Agamben, the early Christian debates about the relationship between God the Father and the Son anticipate this “providential machine.” Much of the first half of the book is given over to an extended genealogy, a survey of how Christians understood oikonomia, both God’s economy ad intra (among the three persons of the Triune God) and God’s economy ad extra (God’s providential relationship to creation, principally in the incarnation). Frustrated by modern theologians’ efforts to tackle these topics separately, Agamben insists that there is only one divine economy in classical Trinitarian theology, that in both ad intra and ad extra we see the same structure: God the Father retreats from messy interaction with the world in favor of an impotent sovereignty, ceding his place to the Son or Word, who creates and saves, establishes and governs.

Marshalling an impressive array of ancient sources from the Greek and Latin fathers of the church, Agamben buries the reader in an overwhelming deposit of learning. The result is rather numbing, even for me, who has a fair amount of experience reading these source texts. If the reader maintains vigilance, however, and tries to follow Agamben’s narrative closely, the thread of the argument begins to disintegrate. On nearly every page is a forced or tendentious interpretation, an important omission or elision.

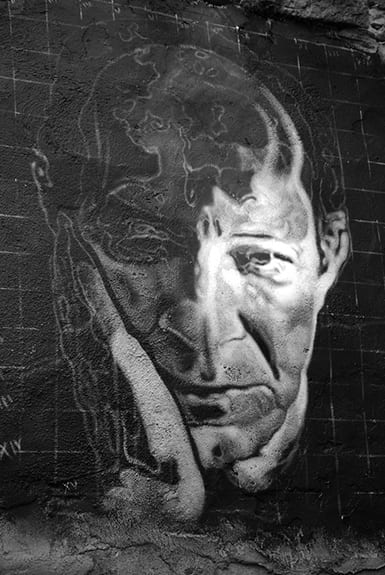

Giorgio Agamben, Abode of Chaos, Saint-Romain-au-Mont-D’or. Thierry Ehrmann via Flickr, CC by 2.0

Out of frustration with The Kingdom and the Glory, I took up The Signature of All Things I wondered whether I was perhaps judging its genealogy by the wrong criteria. Although The Signature of All Things appeared in English well before The Kingdom and the Glory, it was written after. It amounts to a pause in the Homo Sacer series, an opportunity for Agamben to reflect on his methodology under three broad rubrics (paradigms, the science of signatures, and philosophical archaeology), especially as it relates to Michel Foucault’s. One thing is clear: Agamben, like Michel Foucault before him, does not intend his genealogy to deliver “something like a cause or a historical origin.” Trinitarian oikonomia is not the historical source for the modern political division of kingdom from government; one cannot trace the uninterrupted development of Trinitarian oikonomia from the fourth and fifth centuries to the emergence of the “providential machine” in early modernity. Rather, Agamben insists, Trinitarian oikonomia is a “paradigm” “whose aim was to make intelligible series of phenomena whose kinship had eluded or could elude the historian’s gaze.”8 When you press on this claim, however, the book doesn’t offer a very precise or satisfying account of either intelligibility or kinship, leaving the impression that the “paradigm” of Trinitarian oikonomia operates on the level of a grand analogy. The modern political structure of kingdom divorced from government, with only glory serving as the glue, is somehow like Trinitarian oikonomia. But the “somehow” remains frustratingly opaque.

Dissatisfied with this genealogy, I returned to The Church and the Kingdom and its central provocation: deaf to its messianic vocation, its parochial welcoming of the kingdom on offer in every moment, the church has settled into katoikia, that is, how a citizen of an earthly kingdom dwells—very much at home, complacent, complicit. In other words, for Agamben, the church has chosen one kingdom over another (despite Jesus’s explicit imperative to render unto Caesar only what is Caesar’s). Here, then, is Agamben’s tetrarchy: two churches and two kingdoms. One church, deserving of the name, that (in the words of “O Come, O Come, Emmanuel”) “mourns in lonely exile here,” preparing for the messianic kingdom of the now, a church that perhaps never arrived, but has certainly since departed; another church, or “church,” cozying up with another, impotent “kingdom” and its glorifying and governing ranks, a “church” that puts down roots, settling in for the long wait on a Messiah who will never come, not because the Messiah is a myth, but because he is no longer welcome, not now at least.

At the same time as these books of Agamben’s appeared, Simon Critchley, the Hans Jonas Professor of Philosophy at the New School for Social Research in New York City, published The Faith of the Faithless, a companion volume to his 2007 Infinitely Demanding.9 Critchley remarks that very often at the very end of Agamben’s books—even on the last page—Agamben offers an opening, a way out of the prison of the “providential machine,” that is, the collusion of the “church” and the “kingdom” in the second, debased sense. In the very last sentence of The Kingdom and the Glory, Agamben delivers: “Establishing whether . . . glory covers and captures in the guise of ‘eternal life’ that particular praxis of man as living being that we have defined as inoperativity . . . is the task for a future investigation.”10 The key word here is captures. The collusion of “church” and “kingdom” threatens to choke out life, or anything other than the barest of life. Agamben leaves us with the question: is there a way for life to escape the vacuous economy, the collusion of “church” and “kingdom”?

Yes, perhaps, but only by way of “inoperativity,” Agamben’s translation of the Greek word katargêsis. According to him, our fragile freedom lies herein. The verb katargein is one of the apostle Paul’s favorites (of the 27 instances in the New Testament, 25 are in Paul’s epistles). Its most famous appearance, and one that has garnered a lot of attention from philosophers, is 1 Corinthians 1:28: “God chose what is low and despised in the world, even things that are not, to bring to nothing [katargêsêi, or “to render inoperative”] things that are.” For Agamben, Christ comes, “low and despised,” calling “the refuse of the world, the offscouring of all things” (1 Cor 4:13)—what Critchley colorfully characterizes as “the human dregs and nail clippings of the world—the shit of the earth.”11 This lowly coming and calling effects our katargêsis, our negation, understood as our being rendered “inoperative.” What Christ does is to say “no” to our place in the work of the world, makes us useless for its purposes. When, in 1 Cor 7:29–31, Paul speaks of the moment (kairos) having “contracted” (sunestalmenos), he advises his charges to be “as not” (hôs mê)—not husbands or wives, not mourners or rejoicers, not buyers or sellers. Only by being rendered “as not,” “inoperative,” or useless can we recover our new use: “if you can become free, make use of it” (1 Cor 7:21). To put a new spin on Carl Schmitt, you could say that we need to enter a “state of exception”—exception from the callings and claims of the worldly “kingdom”—in order to enter a state of inception, to welcome the Messiah in the moment as Paul did (think of Galatians 2:20: “it is no longer I, but Christ who lives in me”).

This notion of katargêsis, or “inoperativity,” was the second feature of Agamben’s provocation that sparked my imagination and renewed my call to ordained ministry. To my mind, he named a crucial aspect of Paul’s insight into Christ’s coming: that the Christ event arrests us, stops us in our tracks, renders us useless so as to be put to another use; and that, apart from this “inoperativity,” we enjoy only an illusion of freedom. Combined with the distinction between temporalities—paroikia versus katoikia, sojourning versus dwelling—this meant that the Christ event was also meant to arrest us in time, to negate our complacent and complicit temporality, and usher us into a new time. But if the church is really meant to prepare for the messianic kingdom of the now, how does it render the members of its body “inoperative”? And if the church is not living up to its annulling vocation—the call to be “as not”—then how can we help do so?

Critchley regards “inoperativity”—this state of exception for the purposes of inception—as essentially escapist. For Agamben, life seems to have the fragile possibility of exempting itself from the domain of law, from the kingdom and its government. Messianism is a sharp rebuke of the law—not just Jewish law, but all law. Life is possible only as lawlessness, what Critchley calls Agamben’s “radical antinomianism.”12 His first critique is that Agamben, following Harnack (and, curiously, Heidegger), is a pseudo-Marcionite. Marcion was a second-century Christian who regarded the God whom Jesus proclaimed to be an “alien God,” a God who stood above and apart from the God whose notorious exploits and capricious demands are recorded in the Hebrew Bible.13 His was a vision of Christianity shorn entirely of Judaism; his Bible was a whitewashed version of the Gospel of Luke, along with 10 letters of Paul. What makes Agamben a Marcionite, Critchley contends, is his “emphasis on a radically antinomian conception of faith.”14

What sort of community can such a lawlessness sustain? This is Critchley’s second and main criticism of Agamben, that his pure messianism of the moment cannot admit of political associations or actions: “At its most extreme it encourages a politics of secession from a terminally corrupt world.”15 This too, for Critchley, smacks of Marcionism. He reminds us of Harnack’s claim that Marcion “calls us, not out of an alien existence in which we have gone astray and into our true home, but out of the dreadful homeland to which we belong into a blessed alien life.”16 Curiously, in his first book to appear in English, in 1993, The Coming Community, Agamben does give an example of a salutary political community, namely, the protests in Tiananmen Square. But as if to underscore the fragility of any messianic lawlessness, he reminds us that “sooner or later, the tanks will appear.”17 A dreadful homeland indeed.

Critchley stands apart from Agamben for having faith in the politics of resistance.

Critchley stands apart from Agamben for having faith in the politics of resistance. He has sharp words not only for Agamben, but also for his contemporaries Alain Badiou and especially Slavoj Žižek, for indulging in what he regards as paralytic political defeatism. He shares Agamben’s bleak outlook on contemporary world politics: liberal democracy is a self-deluding crust, thinly protecting the plutocratic elite from the reality of the plight of everyone else, at home and abroad. But what is needed is not to wait on the great revolutionary gesture, as Žižek would have us do, but rather “the creation of interstitial distance within the state and the cultivation of forms of cooperation and mutuality”—in other words, a kind of anarchic communitarianism.18

Two strands of Christianity contribute to Critchley’s imagination of what these new “forms of cooperation and mutuality” might be. The first goes under the name of “mystical anarchism”: Critchley has a romantic fondness for the self-annihilating ethics of Marguerite Porete, the twelfth-century Beguine who was burned at the stake for heresy on the basis of her book, The Mirror of Simple Souls. For Critchley, Porete’s “auto-theism,” or deification through annihilation of the self, holds out hope for “the creation of new forms of life at a distance from the order of the state,” the “possibility for a life of cooperation and solidarity with others.” The second strand is Paul’s fragile communities of faith, what he calls “a politics of the remnant, where the off-cuttings of humanity are the basis for a new political articulation.”19 Again, just as with Agamben, Critchley regards the danger of both Porete’s mystical anarchism and Paul’s radical politics of faith (as opposed to law) to be “a politics of secession,” a form of political association that does not stand in critical tension with the state but pretends to exempt itself entirely.

Agamben seems keen to avoid the secessionist temptation, at least when he speaks in front of bishops. He concludes The Church and the Kingdom by speaking of two opposing forces of history: of the first, what he calls “Law” or “State” (that is, the partnership between “Kingdom” and “Government”), he is certainly critical, here but especially elsewhere; the second, the messianism of church and kingdom (in the first and proper sense), is precisely what he wishes to recover. Whereas in most of his other books, the former force is figured as the prison incarcerating the second, the law that chokes out life, here he rather surprisingly recommends a “dialectical tension” between the two, insisting that such a tension “is the only way that a community can form and last.” “This tension . . . seems today to have disappeared”: the ellipse with two foci has collapsed into a circle with a single center, leaving a “hypertrophy of the law.”20 We have been rendering only unto Caesar because there is no longer any way to render unto God.

But this concluding recommendation of a dialectical tension between church and state hardly seems the radical revolutionary gesture of secession Critchley warns us of. Rather, it appears as a conciliatory call for the return of the church: only a church that sojourns rather than dwells can stand up to the force of the state. In Paul’s logic, the church’s “power is made perfect in weakness” (2 Cor 12:9). This leaves us with the pious conclusion, however, that our political salvation lies squarely in the hands of the church: the parousia depends on paroikia. Without the church, we cannot but suffer under the “hypertrophy of the law.”

What strikes me most about The Church and the Kingdom, then, is not only its conciliatory tone, or even its unexpected piety, but rather how deeply Roman Catholic it is. Ironically, Critchley claims that in forwarding a radically antinomian faith, Agamben is carrying on the Protestant project of Luther, Harnack, and Heidegger. But Agamben seems to have none of Critchley’s enthusiasm for what we might call “cellular” Christianity: small, “interstitial” forms of religious association that might somehow successfully resist the state. On the contrary, he addresses the church in Paris, although it could equally well be in Rome: only this church, the very “church” that has settled into katoikia, can recover its messianic vocation of paroikia and save us. It is almost as if Agamben believes in apostolic succession and the throne of Peter: only the church that first had the messianic vocation could then lose it. But whether the church that arrives (or perhaps returns), emerging from within the “church,” will bear any resemblance to that present placeholder is a question left open, as open as the question of whether the parousia of the Messiah will bear any resemblance to Jesus of Nazareth.

I suppose, in retrospect, Agamben helped reawaken my call to ordained ministry because he articulated an aspiration to help birth the church from within the “church,” to resist the “kingdom” by learning how to prepare for the kingdom. It helped me make sense of my own calling, and that of many dear friends who had devoted their lives to the church. I too wanted to embark on a ministry of time, to explore temporalities other than dwelling in empire, or its late modern descendent, consumer capitalism.

But then why have I stepped away from ordination, and even more, from the faith? There’s no single answer to that question, of course, but once again my only sense of an answer hinges on time and temporality. There is much in Agamben’s account of messianic time that still resonates deeply with my sense of what the gospel is about: how to sojourn rather than dwell, and the freedom of uselessness and inoperativity. I suppose, if I am honest with myself, I have shed—like scales from my eyes—the dialectics of church and kingdom that have framed these temporal possibilities. And I have grown impatient with what I perceive as the limited temporality on offer in Agamben’s messianic vocation, in which there are two, or maybe three, kinds of time. According to him, there is 1) chronological time—the time we live in “before” the Messiah; there is 2) eternity—the end of time, “after” the return of the Messiah; and there is 3) messianic time—“the time that remains” (the title of perhaps Agamben’s most famous book), the time we live in now, the time it takes for time to come to an end.

In The Time That Remains, Agamben renders these as A, B, C (or A, C, and B, as I have laid them out) and offers different diagrams for explaining their relationship.21 In The Church and the Kingdom, he says of messianic time that it “is not the end of time but the time of the end. What is messianic is not the end of time but the relation of every moment, every kairos, to the end of time and to eternity . . . the time that remains between time and its end”; “what is at issue is a time that pulses and moves within chronological time, that transforms chronological time from within.”22 That’s it: there’s time and eternity, and the time that remains in which every moment in time can somehow relate to eternity. No doubt someone will tell me that I have misunderstood Agamben’s messianism, and perhaps I have. But I am left wanting precisely more pulse, more movement, more transformation than this tripartite temporality offers.

These temporal options now strike me as limited by an all-too-human frame.

These temporal options now strike me as limited by an all-too-human frame. In this frame, we imagine ourselves part of a narrative history, unfolding in time, in which we humans are at the center, led along by a God, and his Messiah, who are also disturbingly human in their outline; that the significance of this narrative lies somehow in its culmination, its end, and perhaps our own; and maybe, maybe, that the end of this narrative can somehow be experienced as it is still running its course, that the end can break into the time that remains. I want more options from whatever it is we call time, and I think that time can accommodate that request—indeed, that time eagerly waits on us, as it were, offering us much more, a much wider array of temporality. I don’t presume to know what that “more” is yet, never mind how to put it in words. But I have glimpsed it, just, and not through human history, or by imagining its end. But rather, in recent years, by tarrying with what is not human, what is more than human and all around us.

I realize now that I have not only left the “church,” but perhaps also the church (if it was ever here), and I have even given up on waiting on the messianic kingdom of the now. It is almost as if that Easter morning in Jerusalem was a harbinger of a resurrection I misunderstood then, and also for years after. Yes, I was fleeing the walls of the “church” and its limited teaching about time, fleeing for my life—for life, including my own. But not, as I came to think with Agamben’s help, so as to be able to enter it again, and help it learn to sojourn rather than dwell, be a tent rather than a temple. Rather, I was fleeing the walls of the “church” so as to seek new teachers of time and temporality. There, I found myself, in the garden, basking in the morning sun, feet resting on ancient stones, addressed by late spring flowers and the soil that held them. I was amid what Antoine de Saint-Exupéry celebrated as Terre des hommes: terre, “earth,” amid what his English translator rendered as “wind, sand, and stars.” I am now more drawn to the language and rhythms of wind, sand, and stars than those of messianism. These are my new teachers of time. And like Saint-Exupéry, who in addition to being a writer was also a pilot, I want to explore.

Notes:

- Alfred Loisy, The Gospel and the Church, trans. Christopher Home (Isbister & Co., 1903); published first as L’Évangile et l’Église (Picard, 1902).

- Loisy, The Gospel and the Church, 166. Quoted in Agamben, The Church and the Kingdom, 27. The quote attributed to this “French theologian” reads, “Christ announced the coming of the Kingdom, and what arrived was the Church.”

- Alfred Loisy, Autour d’un petit livre (Alphonse Picard et fils, 1903), 159: “l’Évangile et l’Église sont dans un rapport identique avec le royaume: ils le préparent immédiatement.”

- Agamben, The Church and the Kingdom, 41.

- Ibid, 26.

- As quoted in ibid., 5.

- Carl Schmitt, Political Theology II: The Myth of the Closure of Any Political Theology (Polity Press, 2008), 67; as quoted in Agamben, The Kingdom and the Glory, 72.

- Giorgio Agamben, The Signature of All Things, trans. Luca D’Isanto and Kevin Attell (Zone Books, 2009), 31.

- Simon Critchley, Infinitely Demanding: Ethics of Commitment, Politics of Resistance (Verson, 2007).

- Agamben, The Kingdom and the Glory, 259.

- Critchley, The Faith of the Faithless, 159.

- Ibid., 15.

- See Adolf von Harnack, Marcion: The Gospel of the Alien God, trans. J. E. Steely and L. D. Bierma (Labyrinth, 1990). For a more recent appraisal of Marcion, see Judith Lieu, Marcion and the Making of a Heretic: God and Scripture in the Second Century (Cambridge University Press, 2015).

- Critchley, The Faith of the Faithless, 199.

- Ibid, 202.

- Harnack, Marcion, 139; quoted in Critchley, The Faith of the Faithless, 202.

- Giorgio Agamben, The Coming Community, trans. Michael Hardt (University of Minnesota Press, 1993), 86.7.

- Critchley, The Faith of the Faithless, 17.

- Ibid, 143, 159.

- Agamben, The Church and the Kingdom, 35, 40.

- Giorgio Agamben, The Time That Remains: A Commentary on the Letter to the Romans, trans. Patricia Dailey (Stanford University Press, 2005), 63–64.

- Agamben, The Church and the Kingdom, 8, 12.

Charles M. Stang, Professor of Early Christian Thought and the director of the Center for the Study of World Religions at Harvard Divinity School, focuses on the development of asceticism, monasticism, and mysticism in Eastern Christianity. His most recent book is Our Divine Double (Harvard University Press, 2016).

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.

Hello,

Your article provided a great explication of Agamben’s work and goals through your comparative understanding of Agamben and similar scholars. I particularly enjoyed how these works seem to have come just at the right time in your life. I think because of that, you connected with the material on a very vulnerable level and wrote this beautiful culmination of ideas. I admire your journey, and I wish you the best.

Stay well,

O