Perspective

Flipping the Script

By Wendy McDowell

“I hope you have not been leading a double life, pretending to be wicked and being good all the time. That would be hypocrisy.” —Oscar Wilde, The Importance of Being Earnest

Research reveals that most of us have a high tolerance for hypocrisy in ourselves but a low tolerance for hypocrisy in others. We tend to be blind to our moral failures and to play up our moral achievements. And it goes deeper than this—we will distort or forget aspects of our wrongdoings “to return to the comfort of believing in our capacity for good” (a phenomenon known as “ethical amnesia”).1 So, not only do we fail to predict our own moral behavior accurately, we can believe we behaved ethically even when we didn’t!

We shouldn’t need experiments to know this about ourselves, should we? Past and present realities of genocide, endemic sexual assault and child abuse, internment or banishment of marginalized groups, human trafficking, mass incarceration, environmental degradation, and militarization of borders show us how easily human beings can slide into immorality, cruelty, and violence.2

When I first moved to New York City in the early 1990s, it struck me right away how a homeless person was mostly treated with a mixture of indifference, disgust, and social distancing, as if he was a duffel bag stuffed with rags lying on the subway seat (or park bench or sidewalk) and not a breathing man. I noticed this collective behavior, my conscience “pinged,” and yet I fell right in line. Soon I was nonchalantly stepping over disheveled bodies and moving to the other end of a subway car to avoid their stench. I so wanted “to be a New Yorker,” and this was how New Yorkers acted.

In this issue are models of courageous practices, scholarship, and creative work grounded in communities already practiced in the art of script-flipping.

One day, a homeless woman knocked on our door (we lived in an apartment building on 123rd street). In a shaky voice, she asked if she could come in to get warm. I’d heard her trying other doors in the building; I’d also heard the rude refusals and doors shutting in her face. By the time she made it to our door, she was trembling uncontrollably and looked like she might crumple to the floor. I asked if she was sick, and she said, “Yeah, I’m drug sick.” I was in the middle of making a stew, so I kept the door open and conferred with my partner. “We have enough stew to share,” I said. He agreed. I covered her with an afghan as she napped on our pull-out futon (also our bed). We woke her when dinner was ready, she ate a few bites with us, and then we called the shelter she liked best to ask if they had an open bed. We hailed a cab, gave the driver enough money to take her to the shelter, and said goodbye.

I only exchanged small talk with Mary (yes, Mary really was her name!), and I never saw her again. But after this encounter, the script was flipped. I started sitting near the disheveled man on the train when others moved away, no matter if he reeked. My disgust was no longer aimed at vulnerable, often addicted, people living on the edge, but toward those of us (myself included) who exhibit “the ability to be smug about terror.”3

This is one of the more challenging issues of the Bulletin in recent years, because many of the authors are doing, in one way or another, “script-flipping work.” I am indebted for this term to Thelathia “Nikki” Young, who explains that black queer ethics “has the audacity and rage to do this script-flipping kind of work,” while it also articulates a “substance of things hoped for.” Young situates Black Panther as both “speculative fiction and ethical action” that “allows one to confront the lie of one’s own nonexistence” and “makes room for the un/making and then remaking of subjectivity and selfhood for black folks.”

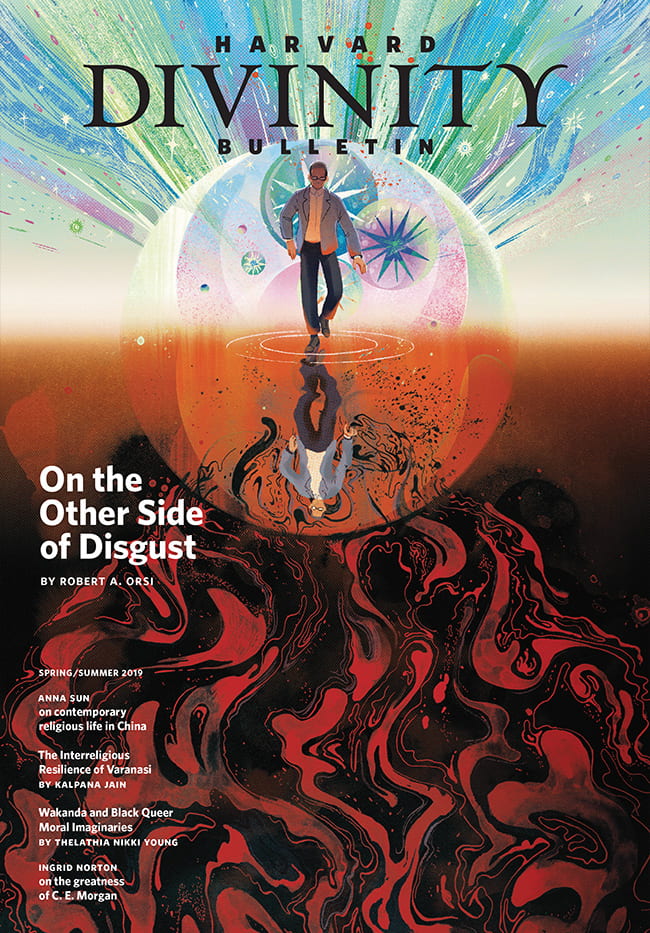

Other authors here are not afraid to take on controversial—even taboo—topics and tension points, and to flip the script. Robert A. Orsi’s response to the crimes and cover-ups of sexually predatory priests does this in multiple ways: by turning on its head the notion that there is a “crisis” at this moment in Catholic history, by showing how the “fall[ing] back on the good religion/bad religion distinction” diverts us from “the painful truth of religion in human life,” and by “proposing to take disgust itself away from the powerful and use it against them.”

Linda Dittmar’s memoir of two trips to Caesarea views the vistas of her native Israel from a perspective of destruction and absence. Once she becomes attuned to seeing the minarets and mosques in the landscape, “loom[ing] as a spectral witness to the Palestinian village that used to be here before the Nakba,” she finds she can’t go back. Recognizing her inherited position of dominion, she must confront the “willed blindness” in herself and her peers, as she realizes “how comfortable we are with oblivion.”

Here also are models of courageous practices, scholarship, and creative work grounded in communities already practiced in the art of script-flipping. LeRhonda S. Manigault-Bryant directs us to visual media projects that allow black women “the opportunity to tell our own stories—of our bodies and our faiths—and . . . dismantle the bodily fictions that would diminish the positive ways we see ourselves.” Celene Ibrahim, Kalpana Jain, and John Gifford focus on the actions of ordinary people, religious leaders, activists, and chaplains to get to know and nourish others, nothing less than the day-to-day work of interreligious bridge-building and peacekeeping.

Anna Sun encourages us to break out of “the institutional and identity-based framework of an unacknowledged monotheism” and to instead look at contemporary religious life in terms of a “ritual rationality” that allows for multivalent, practice-oriented, fluid realities. And what better models do we have than the faith-based public intellectuals in the Cornel West/Jonathan Walton course, whose lives exemplify the humanity-validating work of freedom, fugitivity, and love that expands our moral imaginaries.

Whether opening up intellectual, artistic, political, or ritual spaces, the stakes are communal and intergenerational. It’s not a contest over how “woke” we are, but about what we generate and pass down. As Jain and Young emphasize, the stories we tell and the worlds we imagine write the scripts for future generations. “What kinds of souls, bodies, and lives are we making possible?” Young asks.

Notes:

- This quote, and the study results, are from Jared Piazza’s “Why We Are All Moral Hypocrites—and What We Can Do about It,” The Conversation, October 11, 2016, theconversation.com. Other research has shown how susceptible we are to authority figures, social influence, and persuasive techniques, how we are less inclined to act ethically in a group due to pluralistic ignorance and diffusion of responsibility, and how our decisions and actions are driven by our biases (explicit and implicit).

- James Waller’s book Becoming Evil: How Ordinary People Commit Genocide and Mass Killing (Oxford, 2002) is insightful about the conditions that can lead to genocide, and how easily “intelligent and cultured” people can be persuaded to participate in atrocities. Two mechanisms stood out to me in Becoming Evil: how our beliefs start to conform to our behaviors (we tend to think it only goes in the other direction, that our behaviors conform to our beliefs), and how perpetrators will go along with what they think are “tiny things,” only to discover that they are soon being asked to engage in explicitly violent actions. Both points made me realize that once you’ve put yourself on the slide into cruelty, it becomes that much harder to back up on the slide, and only too easy to accelerate downward.

- Ernest Becker, The Denial of Death (Simon & Schuster, 1973), 59. As I changed my own behavior, I began noticing other New Yorkers who were resisting the social construction of cruelty against street people. It is not an achievement to finally acknowledge the humanity of another person; this should be normal. My shame about only too quickly conforming to a dehumanizing script made me realize I needed to be more vigilant, to live by a stricter moral code. Still, I continue to face my own “willed blindness” as a white, cisgender, U.S. citizen.

Wendy McDowell is editor in chief of the Bulletin.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.