Featured

Echoes of a Legendary Queen

Contemporary women writers revise and recreate Sheba/Bilqīs.

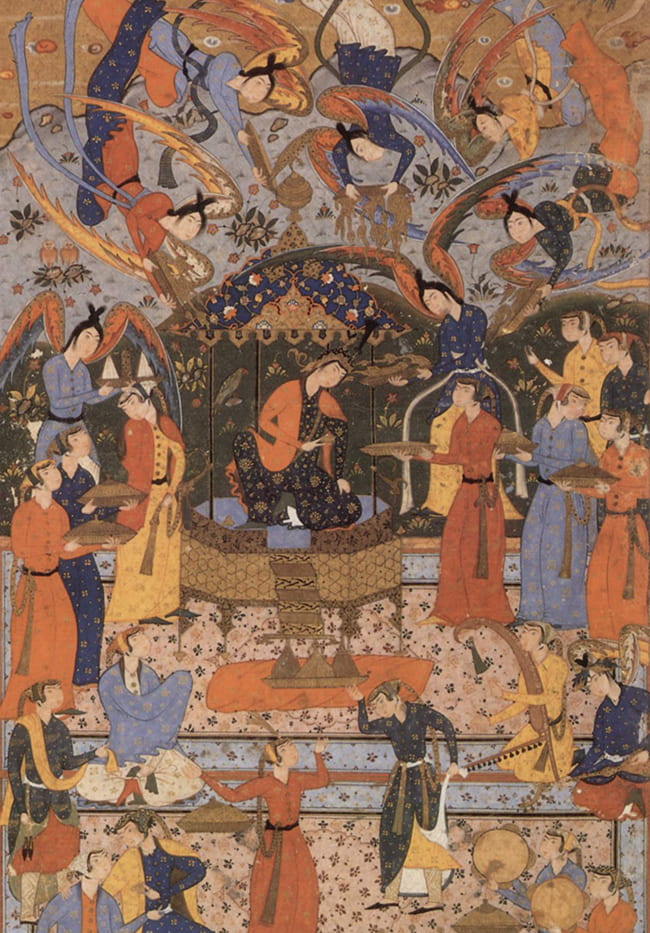

Schahnama des Firdausi, Queen of Sheba (16th century). The Yorck Project, Wikimedia Commons, PD

By Wafaa Abdulaali

A fair land and an oft-Forgiving Lord.

—Qur’an, Saba’, 34:15

The Queen of Sheba is one of the very few female figures who appear in the sacred texts of all three Abrahamic faiths: Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. In the Jewish and in many Christian traditions, she is known by her land’s name, Sheba, or the south, referring to the area now known as Yemen. Both the land and queen were also known as Bilqīs, from balmaqa, meaning moon worshiper.1 In Ethiopian Coptic legends, she is Makeda. The Hebrew Bible recounts:

When the queen of Sheba heard about the fame of Solomon and his relation to the name of the lord, she came to test him with hard questions. Arriving at Jerusalem with a very great caravan—with camels carrying spices, large quantities of gold, and precious stones—she came to Solomon and talked with him about all that she had on her mind. (1 Kings 10:1–2)

In the New Testament, she is the woman who Jesus foretells will rise up and condemn the unbelievers: “The Queen of the South will rise at the judgment with this generation and condemn it; for she came from the ends of the earth to listen to Solomon’s wisdom, and now one greater than Solomon is here” (Matthew 12:42; also Luke 11:31).

In Islam, she is the wise, democratic queen who searches for truth, finds it with Solomon, and abandons sun worship in favor of the one God. In the Qur’anic chapter “The Ants” (sūrat an-naml), the hoopoe, a member of the Conference of Birds subject to King Solomon’s power, informs the king about the rich and prosperous land of Saba’ (Arabic for Sheba), whose queen and her people worship the sun instead of God. Solomon sends the hoopoe with a message to Sheba that reads: “In the name of God, the Compassionate, the Merciful; be ye not arrogant against me, but come in submission (to the true religion)” (Qur’an 27:30–31). In response, the queen sets out on the long trip north to Jerusalem, where Solomon rules. Her caravans carry all kinds of precious gifts: gold, gems, spices, myrrh, and frankincense. She comes to test Solomon with riddles, and he answers them wisely.

Folktales and apocryphal accounts from the Jewish rabbinic tradition, the Coptic Christian tradition in the Ethiopian book Glory of Kings (Kebra Nagast), and the Arab Yemeni tradition have elaborated on the scriptural tales to give Sheba a jinni mother, goat or donkey hooves, and hairy legs. In the Bible, hair is associated with physical and intellectual strength, as in the story of Samson: “If my head were shaved, my strength would leave me, and I would become as weak as any other man” (Judges 16:17). But male tellers of traditional tales have associated women’s hairy legs with the devil or with lesbianism to limit women’s access to political power.

Pre-Islamic and Islamic Arabic traditions describe Bilqīs as the daughter of Hudhad, the Arab king of Himyar in Yemen, who ruled during the eighth century BCE. He was believed to have once saved an ibex from a wolf; after this act of bravery, the animal turned into a beautiful jinni woman whose father, in gratitude, gave her to Hudhad in marriage. From this union, Bilqīs was born. She later inherited her father’s kingdom.

The narrators of Bilqīs’s story emphasize the symbols surrounding her differently, depending on which message they wish to convey. Three animals play significant roles in weaving together the disparate threads of the plot. The first, the hoopoe emissary between Solomon and the queen, is a symbol of loyalty and a good omen. Carolyn Han’s From the Land of Sheba: Yemeni Folk Tales, tells how, in Yemen, the bird is associated with the awaited spring and rains; its presence is a sign for the farmers to begin plowing. The second animal linked to Sheba, the ibex, is associated with worship of the moon, the prime deity of South Arabia—and so Sheba is as well. The third, the ass, connects Bilqīs with the demonic, as the donkey was culturally associated with the devil.

The story of Bilqīs’s jinni mother was also later used to demonize her. Classical Arabic sources claimed that Bilqīs had donkey hooves and hairy legs. She was said to have used the help of the jinn to build her great dams, including the Ma’rib Dam, an account which deflated her capabilities and achievements as a woman. Not only that, but the hairy legs, distasteful to men, needed to be depilated in these accounts, a symbol of overpowering the queen and seizing her kingdom (again, with parallels to the Samson story). Sheba has also been described as a lesbian, with hundreds of women among her entourage, though Arab historians have distinguished this Bilqīs from the queen mentioned in the Qur’an.2

All three religions agree that the queen of Sheba converts to the “true” religion of Solomon and that she is a pious convert. They differ as to which part of her encounter with Solomon they emphasize, particularly in the initial confrontation between Solomon and Sheba. In rabbinic accounts, Solomon is said to have tricked the queen into lifting up her skirts upon entering his palace hall. In the Qur’an, however, the story of the queen baring her legs implies something quite different. She bares her legs only after being confused by the nature of the surface of the royal hall where Solomon receives her. She mistakenly thinks it is made of water, and only after lifting her skirts and cautiously trying to dip her legs in what she thinks to be a pool does she realize it is actually a glass floor. Solomon also presents Bilqīs with a disguised, but even more resplendent, version of her own throne in order to test her belief, but she passes the test.

The biblical narration of Sheba’s conversion depicts her as a woman of materialism, in love with wealth, thereby diminishing her as a legendary woman figure. In the Bible, Sheba converts for three reasons: Solomon’s wealth, his wisdom, and God’s love for the people of Israel. She recounts:

In wisdom and wealth you have exceeded the report I heard. How many your men must be! How happy your officials, who continually stand before you and hear your wisdom! Praise be to the lord your God, who has delighted in you and placed you on the throne of Israel. Because of the lord’s eternal love for Israel, he has made you king, to maintain justice and righteousness. (1 Kings 10:7–9)

The Qur’an has a different slant on her conversion. Both Solomon and Bilqīs are presented as equals in wealth and wisdom. Each behaves wisely, courteously, and respectfully toward the other; each addresses the other as royalty. Both are given an abundance of everything (Qur’an 27:18–23). The Qur’an, moreover, chronicles the logic of the queen’s conversion, showing her to be thoughtful and dignified. Bilqīs’s readiness to believe in Solomon’s message has made her a respected and highly dignified woman in the Islamic tradition. Arab traditions do not agree about whether or not Bilqīs married Solomon (their marriage is not mentioned in the Qur’an), but she certainly is believed to have had no former husbands. The Qur’anic account ends with her and Solomon as two elders in the history of belief in God.

The focal point in the biblical Solomon-Sheba story is Solomon’s greatness and the magnificence of his state compared to the humble realm of Saba’. In the Islamic and Arab traditions, quite differently, the story emphasizes the greatness of Saba’ and the wisdom of the queen who rules it. This greatness is reflected in Islamic literature: the Sufi mystic Ibn ‘Arabi (1165–1240), for example, describes the Qur’anic Bilqīs as an icon of knowledge and honorable hard work. In a powerful poem in Tarjuman el-Ashwāq, he portrays her as a person possessing both jinni and human qualities.3

Contemporary women writers have resurrected Sheba, in various versions that reflect the cultures and dilemmas in which they live, and the texts upon which they draw. English and Arabic women’s contemporary adaptations of Sheba’s story differ widely in their vision, and in the revisions and re-creations of this legendary female character and her shrewd matriarchy. They highlight her queenship and empowerment, depicting her as a historical icon. The critic and poet Alicia Ostriker suggests, in Stealing the Language: The Emergence of Women’s Poetry in America, that mythical and historical figures like Sheba or Sappho have “a double power”; they exist objectively in the “high” culture and privately or subjectively in the psyche (213). Ostriker explores women poets’ revisionist mythmaking and maintains that by re-creating such legends or myths, these women poets try to subvert male discourse and lead men’s ears to listen to their language, which destroys “the male hegemony” over language; hence, they redefine both woman and culture (211–212).

Because of the Qur’an’s respectful and solemn image of Sheba, Arab Muslim women writers in general write positively about her as a source of inspiration, seeking in her a maternal lineage or seeing her as a way to deal with male threats. Like their Jewish, Christian, and English peers, Arab Muslim women writers revive her story to highlight Solomon’s hegemony and to take on what they see as “his bullying masculinity.”

Arab women in particular identify with Sheba/Bilqīs for her resistance to abuses of power and violations of dignity. The Lebanese poet Joumana Haddad4 passionately demolishes the image of a queen vanquished by Solomon and insists that Sheba return to give Solomon “his ring / and take back my throne.” In this, Haddad equates Sheba with Lilith, Adam’s original wife, who refused to acknowledge his mastery and insisted on equality—including sexual equality. In the mystical poem “Insight-inspired Kingship,”5 another Lebanese poet, Houda al-Na’mani, portrays the Ma’rib Dam in Yemen, built during Bilqīs’s rule, as a mirror reflecting not only wisdom and knowledge, but also the divine intellect:

If the waters’ path is the birds,

the horse reins follow them.

But the Ma’rib is a mirror,

on which gardens and vines fix their gaze.

Innovatively merging mysticism with politics,6 al-Na’mani mulls over all the conflict on this earth, which she blames on the extremism of the three faiths and on each one’s claim to be the sole carrier of God’s message. She searches for interfaith reconciliation to save humanity from mutual destruction. She takes the story of Solomon and Sheba as an example of reconciliation and surrender to the one word of God, which is immune to difference or discord.

In “Bilqīs’s Riches,”7 the Saudi poet ‘Anūd Arrudhan, reimagines the Qur’anic story of Sheba. She identifies with Bilqīs to resist the traditional view of women and the tribalism that smothers her femininity, curbs her creativity, and devours both her soul and the realm which she has made of “doves, grain, and prayers.” Bilqīs, or the Saudi woman, yearns for a voice and for freedom, for a gender-marked language of her own that can overwhelm the world:

Bilqīs was endowed with all riches . . .

and from my papers, a veil of feeling.

In the morning, I saw her . . . on her throne, building cities of doves, grain, and prayers,

offerings to those heading westward,

from the fear of departure

in the windows of her heart!

In the two poems “Bilqīs’s Sorrows” and “Instincts of the Universe,” the Iraqi poet Bushra al-Bustani also deconstructs the traditional interpretation of the Qur’anic Sheba narrative. In “Bilqīs’s Sorrows” (my English translation appeared in Harvard Divinity Bulletin, Winter/Spring 2010), al-Bustani identifies with Bilqīs and bestows upon her the features of a suffering Iraqi woman who grieves the loss of her country’s glories and wealth under coercion, dictatorship, and war. Bilqīs’s voice roars:

Missiles, alas!

In the serenity of my heart,

the waters retreat.

Wheatfields burn their crops,

the poem breaks its meters,

and the country’s borders blur.

Let your eyes’ tears trickle down into my healing wound.

Give the streams back their shade

and their jubilant secrets.

Take me to the sea, I will search

for my flowers in the rushes

and invite the bounty of your hands to rest on my shoulders.

In “Instincts of the Universe,”8 al-Bustani portrays the queen as passive, having capitulated to Solomon, who sought to neutralize the power of a rival and to dominate her. Al-Bustani calls for the truth to come out and asks historically acclaimed women to stage a revolution against hiding it. Referring to the story of Zulaykha (a married woman who tries to seduce her servant, the prophet Yusuf—Joseph in the Hebrew Bible), the poet commends Zulaykha for treading a no-woman zone in her love for Yusuf:

The historical women revolutionaries wrestle with the ordeal,

chide Sheba for surrendering her throne to a huntsman.

They wave the Zulaykha flag.

It is the truth, bare, in the truth’s enclosure.

The breakthrough truth al-Bustani describes is a woman’s surrender to her feelings and desires, to trusting her own instincts.

The British Pakistani writer Shahrukh Husain assembles a panoply of eight mythical, fiendish women, among them Lilith, Lamia, and Sheba, in her collection Temptresses: The Virago Book of Evil Women. She retells their stories with a focus on the power struggles between these women and the men who try to reduce their roles to those of wives and mothers. She calls Sheba “the greatest femme fatale of all time” (x). However, in her vision of Sheba as a matriarchal figure, she muses on a female monarch synonymous with peace, plenty, and progress for all her people, in contrast to the bully Solomon’s “blustery, bombastic” manner (53). Solomon yells at the hoopoe messengers: “How can a mere woman achieve what you claim? It’s a fantasy! A fabrication! A glamour to deceive and enchant us” (58). Husain analyzes Solomon psychologically, presenting him as a person who has developed complexes because of being cut off “from the love of both parents” (75).

Husain draws from both Arabic folk tales and the Qur’an in her version of the story. Sheba, the daughter of a demoness and a Sabaean king, was “schooled in the ways of sovereignty” (68) and “became mistress of immense wisdom” (67). Husain presents Sheba as “the royal virgin, the widow-queen” (52), worshiper of “Mother Moon” (56). “Unselfconscious about her disfigured foot” (50), in the full bloom of feminine youth, she rules over a lush, green, fabulous kingdom, “the land of peace and plenty” that knows “no war,” where men and women “are highly skilled in the arts and sciences” (57). Sabaean women are “too sophisticated, too urbane, too scientifically aware in this day and age in Sheba, to let themselves undergo [housewife’s] drudgery” (50). Most of the women lost their virginity years ago, but Sheba won’t give in to a man

until the moment when desire was at its peak and her wisdom in full flower and her power at its height. And this would only happen when she had the perfect partner standing before her, who reciprocated her yearning with his mind and body and soul. (52)

A flock of her lovely hoopoes tells her about an insulting message from King Solomon brought by the west wind. She wonders: “Why does he always make war?”—especially “for love of his God. What kind of a god was he . . . who constantly wanted him to fight and kill and then fight some more?” (53–54). A merchant attributes Solomon’s stance to his “attitude to women,” saying, for Solomon, “women were unreliable, immoral and inferior” (72). In deciding not to take offense, Sheba reflects:

. . . When kings attack countries, they leave behind a trail of destruction and death. War releases the lowest instincts in the noblest men. Worse of all, no one wins a war—the cost of both winning and losing is too high. So instead of fighting, I’ll send envoys with gifts of peace and friendship. My next decision will depend on Solomon’s response. (73)

When they meet, Solomon and Sheba test each other with riddles, which both answer correctly. They impress each other and exchange compliments. Solomon brings up Sheba’s hairy legs, saying they puzzle him. He connects hairy legs to the burden of crown and country, a burden he considers unnatural for women to bear. He asks if she “is adapting [her body] to the maleness of the task,” and asks her to depilate in order to “restore the manhood to [her] men” (83).

The encounter moves to a marriage-like consummation, and a child is conceived. Sheba chooses to leave for her country. She believes that, if she stays with Solomon, “there can only be war” (91). She criticizes him for his failure to take any of his hundreds of wives as equal partners. Solomon, for his part, accuses her of exploiting his love and casting him aside “like a useless shell” (90). She finally declares, “We were never meant to remain together, only to transform each other by exchanging wisdom” (91).

In her reimagination of Jewish biblical stories, The Nakedness of the Fathers: Biblical Visions and Revisions, Alicia Ostriker, like many contemporary Western women writers, seeks to redress the disempowerment of Sheba. In “Wisdom of Solomon,” Ostriker gives Sheba a strong voice, creating a powerful conversation between her and Solomon, who appears smitten with Sheba’s charms, mind, and grace. Ostriker puts Sheba at the center of a highly erotic scene where her speech prevails—hence rewriting Solomon’s “Song of Songs” in a female language and trading his linguistic domination for a feminine one. “Sheba’s Proverbs” (a section in “Wisdom of Solomon”) echo those of the Bible, but with a twist: they criticize patriarchy and sneer at what Sheba sees as its folly, concluding with a call for peace:

Some people don’t have the brain God gave a pigeon.

. . . .

A confident man is unafraid of an intelligent woman.

. . . .

Are you nostalgic for matriarchy? A woman ruler can be crueler.

. . . .

A ruler who cannot feed his people invents a holy war.

. . . .

Join the army, travel to exotic places, meet interesting new people and kill them.

. . . .

No joy is like the joy when a tyrant falls.

Make trade not war.

. . . .

Damn prisons! Bless playgrounds! (209–210)

Solomon’s speech seems mournful and reflective; he “lets [his suffering] come up from his feet to his eyes” and broods on his parents, whom he hates. But, Sheba “is bored. She is not so fond of being lectured to” (212). Foreshadowing the Hebrew Bible’s story of Solomon’s abandonment of God (1 Kings 11:4–8), Solomon emerges as skeptical about God and questions his message, including the building of the temple, which he starts to see as too much trouble. Sheba asks the polygamist Solomon to give his one thousand wives and concubines freedom of faith, since he already seems to believe that pluralism and polytheism enrich his kingdom.

African American poets Nikki Giovanni and Maya Angelou envision Sheba as an African woman, beyond borders. Nikki Giovanni’s “Poem for Flora” hinges on the Ethiopian Coptic version of the parable, which Africanizes Sheba. With a play on phrasing from the Song of Songs (1:5), Giovanni claims Sheba as both “Black and comely,” and writes that she wants “to be like that.” In Angelou’s book-length poem, Now Sheba Sings the Song, each stanza faces a drawing by Tom Feelings of black Sheba at different times of her life, from childhood to old age. The poem and the drawings present the shameful history of slavery. The violation of the black woman in body and soul is ever scratched on Sheba’s memory:

Centuries have recorded my features, in Cafes and

Cathedrals, along the water’s edge.

I awaited the arrival of the ships of freedom

On the selling stage as men proved their power in a

handful of my thigh.

Ruth Fainlight, in the eighteen-poem sequence “Sheba and Solomon,” renarrates the story from a woman’s viewpoint using all versions available to her: biblical, Qur’anic, rabbinic, and Ethiopian. The poem starts with a modern young woman reading the Song of Songs; she identifies with Sheba as she encounters her own sexuality. That poem echoes across time and its sources, as does the poem “Sheba and the Trees”: “They say that Sheba was the link between / Adam and Jesus.” As Sheba arrives in Jerusalem and comes close to the bridge across the river, she realizes that it is made of the wood upon which Jesus will be crucified. She bows, weeps, and worships.

“In the Sweat of Horses” refers to a rabbinic version of the story, in which the first riddle Sheba poses to Solomon asks what water comes from neither earth nor sky. Fainlight gives the answer, “the tears of women,” which differs from Solomon’s answer, the sweat of horses. By ending the poem with “Sheba never wept for Solomon,” Fainlight shows that the queen refused to be a commodity for Solomon. In “Their Meeting,” Solomon tricks Sheba into lifting the hem of her skirts, confirming the rumor of her hairy legs. Upon seeing them, he corrects her: “‘You’re beautiful,’ he said / ’but this is wrong. Here in my kingdom, / women and men must be different.'” And in “Legends of Sheba,” the queen links the three faiths: “A pagan, yet she foretold / Islam’s triumph. She acknowledged / Solomon’s true wisdom.”

In “Another Version,” Fainlight weaves in the tale of Sheba/Makeda of Ethiopia. In this Rastafarian knitting of the story, Menelik, the son of Solomon and Sheba, is to revive Solomon’s kingdom, establishing the second Kingdom of Judah in Ethiopia. Solomon now is a “devious” king, and Sheba has come to his court with her son Menelik, “his replica and image.” Menelik steals the Ark of the Covenant and persuades twelve young Israelites

to follow him across the desert and

beyond the mountains to Ethiopia:

a rebellious farewell. His kingdom

would become the second Zion,

and he, Makeda’s cub, be Judah’s lion.

The Rastafarian emperor of Ethiopia prohibited the cutting of hair and stressed the culture and identity of the black race. In the final poem of the series, “Hair,” Fainlight celebrates Sheba’s hairy legs: back home in Ethiopia, “She preferred her legs like this.”

In one of the stories in her collection The Mermaids in the Basement, the British writer Marina Warner retells Sheba’s story from diverse sources using hyperbole, irony, and understatement. She recreates the images of Solomon and Sheba in a secular light, depicting them as flawed and vulnerable human beings. Warner identifies with Sheba as a woman overpowered in the face of male domination and tackles some of the dynamics of male-female relationships, urging women not to succumb to men like Solomon: “Fight back, I said to myself. Resist the longing. Ass’s hooves are fine. Hairy legs are fine. Don’t let yourself hear the song. And don’t listen, when you do” (160). But her demythicization of both Solomon and Sheba is no less political than the other retellings, since she connects Sheba’s visit with her own visit to Jerusalem. Incorporating the reality of contemporary life there, with its absurd security measures, she includes a scene in which the queen’s child attendants are taken aside and frisked by Solomon’s security agents.

In her title poem, “The Queen of Sheba,” in which Sheba visits Scotland with her caravan, the Scottish poet Kathleen Jamie uses Sheba to invoke a contrast between her fantasy of Arabia as an exotic land and Scotland as a shabby, dim land, a place of poverty. She describes Sheba as the epitome of elegance and privileged upbringing, while the Scottish are boorish and uncultured. Jamie gives her neighbor the animal features traditionally attributed to Sheba—tails and hooves—but with affection. Unlike the dignified, wealthy, warm, vivacious Sheba, Jamie’s people and country are dismal and unenlightened. She contrasts elements of contemporary life—cars, prostitutes, police, chlorinated swimming pools, and cheap housing projects—with Sheba’s affluent procession, which includes camels and spices. Sheba is scouring “Scotland for a Solomon!” so that she may ask him some difficult questions. The Scottish men, too ignorant to recognize her splendor, growl, “Whae do you think y’ur?” In jubilation, the Scottish women and Sheba’s female attendants shout, in a collective voice, “THE QUEEN OF SHEBA!” Women understand who she is and are proud of her.

In Stealing the Language, Ostriker writes that the women narrators of myth, whether the writers themselves or the female speakers in the stories, keep “the name but change the game, and here is where revisionist mythology comes in.” She calls the revisionist myth-making poems “corrections; they are representations of what women find divine and demonic in themselves; they are retrieved images of what women have collectively and historically suffered; in some cases they are instructions for survival” (215).

Sheba has an allegorical presence and, as an inspirational force for these writers, bestows power upon them. They understand who she is, and they are proud. For the black poets, she is the incarnation of the African race; for the Iraqi poet, she is the suffering woman carrying the burden of horrendous circumstances. For all, she is a cultural icon and, as such, is used to comment on national identity, gender, and race. For these contemporary women writers, the queen of Sheba also acts to crystallize their views of women’s power in their spiritual and religious traditions.

Notes:

- Archaeological discoveries have indicated that people in the land of Sheba worshiped a trinity of sun, moon, and Venus. See Zaid Mona, Bilqīs: Emra’atul alghāz wa Shayţanatul Jins (Bilqīs: A Story of Riddles and Satanism) (Riadh el-Rayyes Books, 1997), 65–66. Much of the following material about traditional Arab tales is drawn from Mona.

- Interestingly, Mona investigates four versions of the story of Sheba, including the claim of being half jinni, and traces that to deliberate antiwoman narrations, though some dropped this claim and insisted instead on her “hairy legs” to foster scorn of her femininity; Mona, Bilqīs, 86.

- Ibn ‘Arabi, Tarjuman el-Ashwāq, cited in Mona, Bilqīs, 95.

- Joumana Haddad, Al-Nimra al-Makhbū’ā ‘Enda Masqat el-Kaffain (The Panther Hidden at the Base of Her Shoulders) (al-Dār el-‘arabiya, 2007), 20.

- Houda al-Na’mani, Liman el-Ardh Limanellah (Whose Earth Is It? Whose God Is It?) (Dār Huda al-Na’māni, 2006), 74–78.

- See my “Poetics of Sufism and Politics: A Reading in al-Na’mani’s Collection Whose Earth Is It? Whose God Is It?” Journal of Ādāb arr-Rafidain 56 (2010): 87–110.

- ‘Anūd Arrudhan, Wa’ūtiyat Bilqīs (Bilqīs’s Riches) (Dār el-khayyal, 2008), 38–39.

- Bushra al-Bustani, “Ghara’iz al-Kawn” (“Instincts of the Universe”), bbustani.wordpress.com.

Wafaa Abdulaali currently teaches English poetry and translation at the University of Mosul, Iraq. She was a fellow at Harvard Divinity School in 2008–09.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.

Currently obsessed w Makeda’s tale. Ngl, been my this years’ best read yet