Dialogue

Dying in America

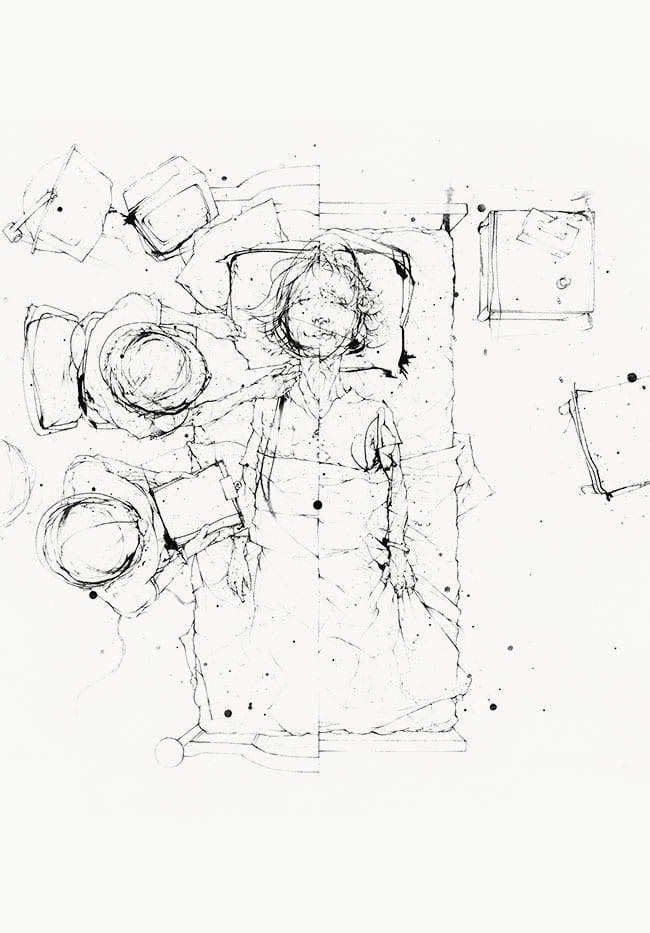

Illustration by Andrew Zbihlyj

By Ann Neumann

Storytelling is inherently hopeful. We tell stories because we hope they will leave an impression, and perhaps even cause our readers to take action. For the past six years I have been writing the stories of the dying—of the patients I encounter as a hospice volunteer, of the doctors and nurses I’ve befriended, and of my own dying loved ones.

This has been the project of a number of writers over the past few years. A national conversation about how Americans die is finally under way.1 As we follow the narrative arc of one human life span, we not only encounter a person’s family history and the well-worn stories the person tells, but we also must confront that person’s bodily decline, the effects of medication, the food desired (or not), the abilities that slip away, the decisions for treatment. We have no choice but to assess how death comes for our loved ones, and we cannot help but consider how it will come for us. We find ourselves comparing the way we die now to how we died even fifty years ago, before the process of death was hidden behind hospital curtains.

Endings aren’t so good for many Americans these days. The social, medical—and, I would argue, moral—backdrop to this conversation is nothing short of a pending national crisis. It is projected that the population over sixty-five will double by 2050, reaching a projected 83.7 million (up from 43.1 million in 2012).2 And, while life expecancy has increased by thirty years in the past century, many of those added years, particularly among economic and racial minority groups, will be spent in faltering or failing health. Because of an innovative—and in many ways beneficial—array of medical treatments, the dying process has been elongated, resulting in a series of treatments that don’t cure and operations that can never be recovered from. The end of life is stretched out to the point where many have begun to ask if there are indeed some things worse than death.

Two women have taught me about the staggering disparities in end-of-life care: good endings are reserved for a privileged few, while caretakers are often underpaid and underappreciated.

Then there is the economic challenge of meeting the health needs of elders. Entire life savings are being spent on nursing homes, medications, medical equipment, and home health aides. And that’s the families lucky enough to have savings. In a country where more than thirty million still lack health care coverage, our resources are increasingly rationed by class.

Four years ago I met two women who taught me much of what there is to know about the staggering disparities in how we deliver end-of-life care. The women have very little in common, but both are intimately engaged in one exhausting task: taking care of a dying body. Their stories demonstrate how quality care and good endings are reserved for a privileged few, and how that care often comes from those who are underpaid and underappreciated.

Evelyn is poised, intelligent, and lives on Central Park West in Manhattan. She was born into a wealthy family, attended private school, became a medical doctor, and then a practicing psychiatrist. When she was diagnosed with lung cancer at the age of seventy-eight, she decided to forego chemotherapy and to enroll in hospice. I met her when the agency I volunteer for suggested that I pay her a visit to see if we got on. Now, every Sunday afternoon, I travel from Brooklyn to Manhattan to visit with Evelyn.

About two months into my visits, Evelyn asked if I would stay and help her interview a new caretaker. Her husband, Melvin, was in the hospital and she was struggling to keep up with the household and her declining health. Maria arrived at the house in the middle of a summer downpour, and she quickly assessed what Evelyn’s needs were. Evelyn hired her on the spot.

Maria is warm, steady, and quick to laugh. Her specialty is one of the most difficult jobs there is: providing whatever a person needs to die. “I do everything,” she told me over lunch one afternoon a few years later. Everything means everything: the shopping, cleaning, bill paying, cooking, medicating, bathing. But Maria also comforts her patients. She is the person most present in their lives. She communicates with their doctors and family. She understands that when they’re irritable or combative, they’re probably physically or emotionally in pain. Maria doesn’t pass judgment and says that this work has made her more patient. “I could never have done this when I was younger,” she tells me. Each night she thanks God for the strength that got her through the day.

Maria is sixty-nine and was born in Panama. She married and raised two children there, working first as an executive secretary and then as an international phone operator, a job that required her bilingual skills. Her brother had moved to the United States and encouraged her to do the same, but she remained in Panama until twelve years ago, caring first for her father and then her mother until they died. When she finally moved to the United States, she enrolled in a training program to become a home health aide. Because the program was attached to an agency, Maria was quickly employed. But she immediately learned that her new field was hobbled by the health care conditions of her new country. The agency charged clients $165 a day but paid employees only $65—under the table. This meant that Maria would have no health insurance, sick days, job security, grief counseling, or opportunities for advancement. When a journalist reported the agency to the U.S. government for employment violations, the Jamaican owner closed it, leaving Maria to rely on her network of Panamanian friends to find a new client. She found Evelyn.

In many ways, Maria’s story is the story of millions of formal and informal caregivers in the United States. Family structures have changed drastically over the past several decades, with generations tending to be far flung across the country. Elders often lack nearby family members as their physical and cognitive abilities decline. Because many elders wish to die at home—and the costs of living in an elder facility make institutional care inaccessible for so many—home caregivers are the fastest growing workforce in the country.3

Though the demand for caregivers is great, their work conditions are dire. When Maria was hired, her role was to do light household chores like grocery shopping, fixing snacks, and washing dishes. She would assist the hospice caregiver, who comes to the house for four hours each day (the amount of time covered by Medicare), with Evelyn’s bathing, medication, and use of the toilet. As Evelyn’s health declined and Melvin came home from the hospital, the couple expected Maria to take on the caregiving for both of them, without an increase in pay. Soon she was asked to cook meals for guests, to clean up bathroom accidents, and to tolerate fits fueled by frustration, depression, and loss of vitality. “She makes me cry all the time,” Maria tells me. “I go to the kitchen and cry and cry and cry.”

As Evelyn lost control of her bowels, her eyesight, and her household, she made up for it by controlling Maria, turning down a fresh glass of water, then requesting it two minutes later, calling her in from the kitchen for no reason, then dismissing her. Evelyn’s behavior is not uncommon in dying patients—who can suffer anxiety, loneliness, pain, and other mood-altering symptoms—but it is exacerbated by her disregard for Maria.

Domestic work, whether it is tending children, caring for elders, or performing household tasks, has always been seen as women’s work, and therefore as less worthy of pay and regulation than types of work that take place outside the home. “Often these individual employment arrangements involve no written contracts, and neither the employer/client nor the worker has clarity around hours, safety standards, responsibilities, and rights,” Ai-Jen Poo, co-founder of Domestic Workers United, writes in The Age of Dignity. “In fact, many individual employers don’t consider themselves formal employers at all—they just think of themselves as paying for ‘a little help.’ “4 In Evelyn’s case, that diminished view of Maria’s employment is compounded by prejudices that are common to her socioeconomic class. Maria and those like her are invisible, their lives unseen, their labor undervalued, their stories unheard.

Why does Maria not protest? Ask for a raise? Refuse to work long, inconsistent hours? Why doesn’t she quit? In part, she is professional enough in her skills to recognize that dying patients are struggling with all kinds of loss that can sometimes be enacted on those around them. At the same time, she can little afford to push back.

“I’m scared. I don’t want to say something and get in trouble,” Maria confides to me. She desperately wants to keep her job. Like many domestic care workers, she is not a legal citizen. Poo writes that one-quarter of all domestic caregivers were born outside the United States, and 50 percent of this group are undocumented.5 When Maria began working with Evelyn, she was paid $13 an hour in cash. Four years later she is paid the same amount but by check, an arrangement that she worries will get her in another kind of trouble.

But when I ask Maria for the primary reason she has stayed with Evelyn and Melvin, she tells me, “I’ve never left a patient. I love what I do.” Maria describes her work as redeeming, a higher calling, and she takes great pride in her patience and tolerance. This is evident when she talks about her prior patient, Rocco. “When I met him he was so skinny,” she says. “He was dirty, he had feces all in his fingers and I was like . . .” She pauses to make a repulsed face. “But then I saw he needed me.” He had no other family. Rocco died in Maria’s arms.

I often wonder: who will care for Maria? She has begun to experience signs of poor health herself. Some tasks, like lifting Evelyn, have become difficult. Each Sunday, when she opens the door for me, we hug and kiss and she whispers updates of each new doctor’s appointment in my ear. Last week she texted me: “Hi Dear. Got through with my tests yesterday and today thank God. I only have one more. They’re gonna put the camera through my nose to look at my throat.” Maria is approaching seventy, she is uninsured, undocumented, and far from her family. She’s in relatively good health now—should her tests come out negative—but what do the next five, ten, or twenty years look like for her?

We know that, even after the Affordable Care Act, there are millions of Americans who still lack basic health insurance—a state of living that often hinders prevention, routine treatment, and even early detection of disease. The greatest deterrents to health care coverage are lack of citizenship, high costs, and lack of access via a state exchange program (particularly in the South where many states do not participate in the ACA). We know that many doctors delay discussions about end-of-life plans with patients—because those discussions are difficult and lengthy and because not all doctors are trained on how to have them. We know that the professionalization and institutionalization of death has removed it from family homes and the public view. We know that the absence of a robust discussion within the general culture about death and dying has prevented elders and the ill from better knowing their options for end-of-life care.

We also know that some minority groups have a long history of distrusting the medical community. Medicine’s cruel history of forced sterilization and unethical research experiments have made some African Americans, for instance, wary of end-of-life discussions and hospice.6 African Americans experience a higher proportional rate of cancer diagnoses but use hospice nearly 5 percent less than whites.7 Others fear they will be deported if they seek care. Still others simply can’t afford it.

Poor education, incarceration, un- or under- employment, pay inequality, food insecurity, inadequate disease prevention, unsafe environments, undocumented status. As these factors play out in our culture, it is very difficult to separate race from class. Overlay all of this inequality and injustice with the state of dying in the United States today: a general lack of knowledge of the dying process, limited or no access to health care, too few forthcoming end-of-life conversations, and a pervasive mistrust, particularly among minority groups, of the medical industry’s intentions—and these factors combine to create a space that is filled by denial, fear, doubt, distrust, and grief. In short, they create all of the conditions for generating hope.

Hope is very present around the deathbed. It can allow the sick to ignore their symptoms and prevent them from seeking help or voicing their wishes. Hope can encourage patients to try one more round of chemotherapy, though its efficacy may be null. Hope desperately pushes families to agree to respirators and feeding tubes that will often only prolong death, not life. One can hope for a miraculous recovery, for the slim odds to be damned, for the disease to disappear, or one can simply hope for more time.

Since Aristotle, we’ve attributed what scholar Adrienne M. Martin has called “a special sustaining power” to hope.8 Health care providers are also susceptible to such hopes. Dr. Ira Byock has said that “doctors’ hopes for their patients” may cause them to overestimate life expectancy.9 Legislators are not immune to hope, either. Since 2014, at least twenty states have introduced “right to try” legislation that allows terminal patients to access experimental drugs before FDA approval—a hopeful gamble that typically fails to deliver. Our current system of health care delivery fails to balance hope for longer, better lives—and better deaths—with the present economic and racial disparities that block millions of people from the care they need.

What Evelyn hoped for was to not die in a hospital. As a former doctor, she understood her diagnosis. She knew she had the money to pay for twenty-four-hour care at home. Evelyn can afford the kind of long death she is having. That knowledge, that hope, and those resources are rare. But even for Evelyn, paying Maria for daily care is an enormous expense, one that our society has not yet addressed. Maria deserves better working conditions, higher pay, sick leave, and all the other benefits that come with legal, structured employment. But we have not yet figured out how to pay for the kind of end-of-life care that Maria and others provide.

To guarantee a good death that is not reliant on privilege, that accommodates patients’ hopes even as it recognizes physical, statistical, and medical limitations, is the ideal. To support the care workers who make that ideal possible should be our goal. Maria hopes some day to retire and receive the kind of care she is now providing for Evelyn. But currently, a good death—as most of us would define it: at home, with attentive and professional caregivers, in relative comfort—is still an anomaly.

Notes:

- Recent books include Katy Butler’s beautiful Knocking on Heaven’s Door, about her unsuccessful attempts to stop her father’s pacemaker, and Atul Gawande’s bestseller Being Mortal, which describes his father’s long decline and death.

- Jennifer M. Ortman, Victoria A. Velkoff, and Howard Hogan, “An Aging Nation: The Older Population in the United States,” a U.S. Census Bureau report, May 2014.

- Ai-Jen Poo, The Age of Dignity: Preparing for the Elder Boom in a Changing America (The New Press, 2015), 160.

- Ibid., 86.

- Ibid., 4.

- Perhaps the best-known example is the U.S. Public Health Service’s long-running Tuskegee syphilis experiment (1932–1972), which tested but did not treat black sharecroppers for their illness.

- See Angela D. Spruill, Deborah K. Mayer, and Jill B. Hamilton, “Barriers in Hospice Use among African Americans with Cancer,” Journal of Hospice and Palliative Nursing 15, no. 3 (2013): 136–44.

- Adrienne M. Martin, How We Hope: A Moral Psychology (Princeton University Press, 2013).

- Amber Bauer, “Talking with Your Doctor about Prognosis,” an interview with Dr. Ira Byock, Cancer.Net Blog, August 14, 2014.

Ann Neumann has written for The New York Times, Bookforum, Guernica, and other publications. Her monthly column, “The Patient Body,” appears in The Revealer, a publication of the Center for Religion and Media at New York University, where she is a visiting scholar. Her book, The Good Death: An Exploration of Dying in America, will be published by Beacon Press in February 2016.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.