Perspective

Connection

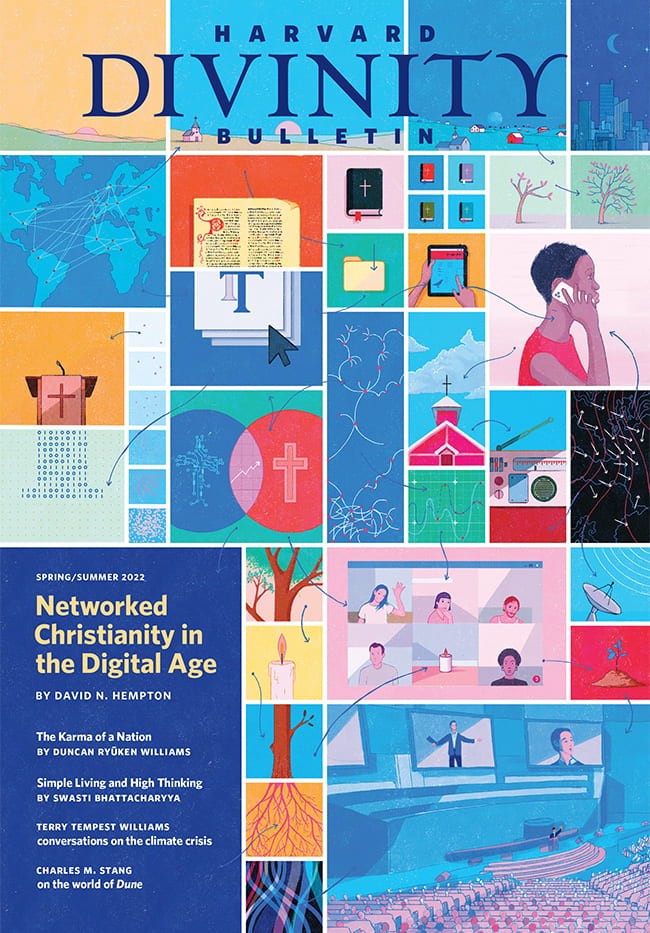

Cover art by Daniel Liévano. Cover design by Point Five Design.

By Gordon Hardy

In March 2020, as the novel coronavirus pandemic spread across the globe, houses of worship faced a difficult reality. In-person religious gatherings, so vital to the lives and spiritual nourishment of billions of people, were also breeding grounds for the deadly new virus. Churches, mosques, synagogues, temples, and other institutions decided (or were obliged by authorities) to stop meeting in person. It was a staggering change to how and where people experienced their religious practices.

My own church, a 180-year-old Unitarian Universalist congregation in New England, was no exception. We’d just moved back into the church after a laborious two-year renovation, and our new spaces suddenly went dark. What we did have, though, was collaboration software; and overnight, we switched to online church. We gathered in our homes each Sunday, opened our computers, and watched as our screens filled with familiar faces watching from their own living rooms. We heard a bit of recorded music and listened as our minister and other worship leaders conducted services online. It took a bit of experimentation, and a lot of effort on the part of the church staff, but over a few months we adapted to the rhythm of this new reality. We even had a social hour after services through Zoom’s “breakout rooms.” The whole experience was different, and not always successful, but we kept our community together through the long two-plus years it took for vaccines to be developed, for safe gathering practices to be refined, and for us to cautiously gather again.

The bonds we so naturally formed in years of in-person fellowship were precious to us, and like people everywhere, we wanted to stay connected to each other in this unknown and, to the modern world, unprecedented time.

Reflecting on that time, I feel that what my fellow parishioners and I worked so hard to preserve was both simple and profound: connection. The bonds we so naturally formed in years of in-person fellowship were precious to us, and like people everywhere, we wanted to stay connected to each other in this unknown and, to the modern world, unprecedented time. It had its costs: the strain on our ministers and staff, the technical glitches that sometimes interfered, the sheer surreal sense of connecting by seeing one another only online. At the same time, there were unexpected benefits: former church members who had moved away could now join us again; new people found us online and started to attend regularly; services were recorded and could be enjoyed online anytime. And as the pandemic began to ease, the joy of seeing one another in person again genuinely lifted our spirits.

Also during the pandemic, by coincidence, Harvard Divinity School’s Dean David Hempton was preparing his Gifford Lectures. The lectureship, named for Adam Lord Gifford, is widely regarded as among the most prestigious and important addresses, designed to “promote and diffuse the study of Natural Theology in the widest sense of the term—in other words, the knowledge of God.” Dean Hempton’s six lectures, titled “Networks, Nodes, and Nuclei in the History of Christianity, c. 1500–2020,” are an extraordinary analysis designed to address the question: What difference would it make to re-imagine the history of Christianity in terms of transnational networks, nodal junction boxes of encounter and transmission, and a greater sense of the core memes and messages of religious traditions and expressions?

In this issue, we present Hempton’s sixth and final lecture: “Only Connect: Networked Christianity in the Digital Age.” It is a careful examination of the dramatic ways the Internet and digital life have engaged and interacted with the whole world of Christian organizations, communities, beliefs, and practices. Like the invention of print, digital tools promise to shape religion in unexpected and previously impossible ways.

“Connection” is a theme running through this issue of the Bulletin. In “The Karma of a Nation,” Duncan Ryūken Williams details the extraordinary determination and persistence of Japanese American Buddhists to practice their traditions while imprisoned in the infamous World War II–era American concentration camps. Swasti Bhattacharyya offers us an insightful account of shared connection and purpose at a women’s ashram in India in “Simple Living and High Thinking.” In the review section, Charles M. Stang considers his connection to the Frank Herbert novel Dune, while Matthew Ichihashi Potts’s Lenten sermon considers our own response to this troubled world. Courtney Sender explores the multi-dimensions of lost connections in Susanna Clarke’s Piranesi, finding that the novel “couples an ethic of caring for the human dead with an ethic of caring for other species’ new life.” We explore in conversation Todne Thomas’s new book, Kincraft, where she asserts that “Making kin is a survival strategy.” And Stephanie Paulsell’s syllabus describes a remarkable class where students read each book twice, in order to “find out what the books have to say to each other.”

This issue’s Dialogue section is unusual for us in presenting a set of conversations from a single series. In fall 2021, noted conservationist Terry Tempest Williams convened a wide-ranging program of online discussions at HDS. Centered on the theme of climate change, “Weather Reports” included brilliant, sometimes heartbreaking perspectives on the recent raging wildfires in the American West; the grief so many experience at the threats to our fragile world; a projection of how humans respond to a near-future climate collapse; and the deep bonds between Indigenous activists, climate, and caribou in the threatened lands of far-north Alaska. Some of it makes for hard reading but leaves room to feel the hope and indomitable spirit of those working passionately to turn us away from planetary destruction.

At this writing, as we continue to tiptoe back into the world outside our living rooms and furtive grocery-store runs, it’s important to remember all we have lost—and all we have gained—through this time. Our shared digital experience opens up new opportunities to connect. And all that we have lost in the pandemic years perhaps, just perhaps, gives us a deepened appreciation for our fragile, beautiful world.

Gordon Hardy is director of communications at Harvard Divinity School.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.