Convocation Keynote

Challenges for a Third Century

Harvard Divinity School should build on its core strengths.

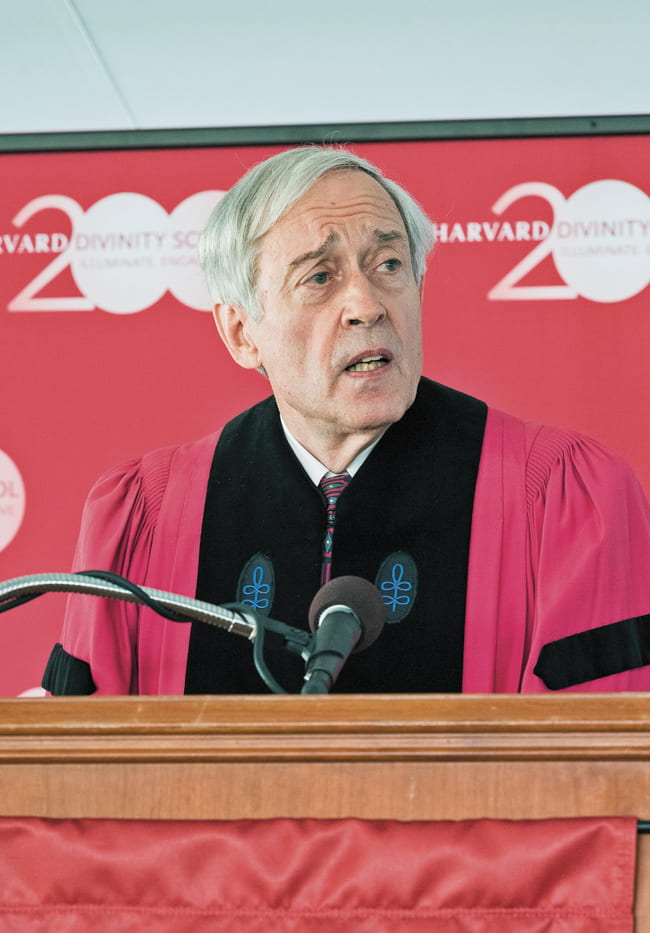

George Rupp speaking at Convocation on August 30, 2016. Photo by Justin Knight

By George Rupp

It would be wonderful if we could gather here simply to celebrate the magnetic power of Harvard Divinity School. . . . But we all know that theological education and the study of religion are under enormous pressure from powerful secular trends and also from a variety of religious movements. For that reason, we must wrestle with the challenge of generating the energy required for HDS to continue to be vigorous and influential.

. . . The crucial goal must be to focus on the core identity of the institution and to build on the central features of that identity—to make the institution more itself rather than to succumb to the temptation of imitating some other institution. That is our challenge for HDS as we move into a third century.

I propose that there are three sets of strengths on which we should focus:

First: the capacity to ground students of all ages in the core traditions of their own communities, including respectful comparisons to other traditions sympathetically understood.

Harvard has extremely impressive resources for grounding students of all ages in particular cultures. . . . There is of course instruction in the full range of European tongues. We also have access to the languages for precious texts and for understanding across lines of conflict or ethnic differences: to name only a few examples, Arabic as well as Hebrew; Sanskrit and Hindi, and also Urdu and Telugu and Tamil; Mandarin and also Yue and Uighur.

Access to a remarkable range of language instruction represents the fact that students can pursue deep understanding of their own traditions and of the language and culture of other communities. This enormous capacity, built up over generations, offers the Divinity School a resource that few of its peers can come even close to matching. The resource belongs to the University as a whole, but the Divinity School must continue to cultivate its own commitment to it. Every student should develop a deep engagement with at least one religious tradition and, in most cases, a sympathetic awareness of at least one further tradition that allows a comparative dimension to his or her studies.

Second: a commitment not only to the descriptive study of multiple traditions but also to normative appraisals. . . . As we all know, there have been times when the emphasis of the academy has been almost exclusively on its crucial descriptive role: to understand and report what has happened in the past and the dynamics of current interactions. The Divinity School certainly shares this emphasis, as its study of particular traditions illustrates. But at its best, HDS has also pressed for engaging the issues of adequacy, of values, yes, of truth. Judgments on such issues are no doubt relative, which is what warrants our apprehension about absolute or unqualified claims for any specific interpretation. Still, the Divinity School has a proud tradition of pursuing normative questions even when the setting of the academy clearly prefers to resist such inquiry.

This normative dimension is most explicit in such traditional fields as systematic theology and ethics. Its implications are also evident in applied parts of the curriculum—fieldwork, for example, and shared worship experiences. Across the range of studies at HDS, there can and should be a persistent awareness of the ways in which claims about values and truth are intrinsic to religious traditions. But they are also at least implicitly present in the impact that religious commitments have on the broader society. It is therefore not only appropriate but required that such claims be subjected to appraisal as to relative adequacy. . . .

Third: a concern to prepare leaders both for particular religious communities and for engaging the dimension of ethics and values in societies around the world.

We are celebrating the bicentennial of HDS. . . . But it is also the 380th anniversary of the founding of Harvard in 1636 as an institution dedicated to the preparation of religious leaders. . . .

In an institution that is intentionally multireligious and insistent on comparative study and normative appraisal that does not take any one authority as self-evident, preparing religious leaders is challenging. Yet professionals who can lead in such complex settings are precisely what our world and our religious traditions desperately need. . . .

Those who study here need not aspire to be—and certainly will not all become—leaders of particular religious communities. But some will, to the benefit of those communities and the whole of our civic life. Of those who pursue other paths, many will help all of us to discern and appraise and develop the religious dimension of the broader culture, including its incipiently global dimensions. Whether in the academy, or in other social, political, economic, and artistic realms, leadership . . . will demand the attention to particular traditions, including comparative dimensions and normative concerns, that characterize the education and research at HDS. It is therefore crucial that this broadly professional role remain salient in the years and decades and centuries ahead.

George Rupp was Dean of HDS from 1979 to 1985.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.