In Review

Bhakti across the Colonial Divide

A Storm of Songs: India and the Idea of the Bhakti Movement, by John Stratton Hawley

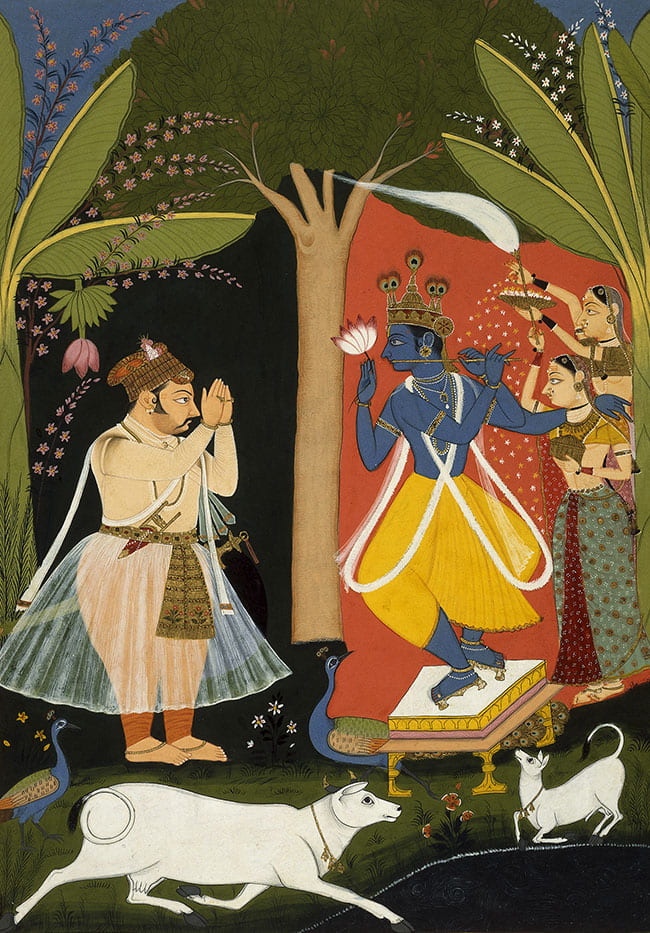

A Rajput king worshipping Krishna (1690–1700). The Trustees of the British Museum / Art Resource, NY

By Anne Monius

A Storm of Songs by John Stratton Hawley (PhD, ’77, Committee on the Study of Religion) marks a significant, wide-ranging, erudite, and beautifully written intervention in the study of South Asian bhakti, or devotion—a word that “implies direct divine encounter, experienced in the lives of individual people” (2). Loosely framed by the religious violence that has dominated global headlines from India over the past two decades, A Storm of Songs examines the popular concept of bhakti as a “movement” (bhakti āndolan in Hindi) that coalesced, in tandem with

India’s struggle for independence, as a narrative of national integration, highlighting vernacular song, the mutual companionship of poet-saints, social inclusion, and personal experience (6–7). Focusing on “the idea of the bhakti movement . . . itself [as] a product of history,” Hawley poses a set of fascinating, interrelated questions (9): “How did the idea of the bhakti movement become such an important intellectual force? Where did it come from? When? Under what circumstances, political and otherwise? In what languages and owing to the efforts of what groups and individuals?”

In seven chapters, Hawley lays out the development of the idea of bhakti as a protodemocratic movement of people, ideas, and institutions from its early modern roots through the twentieth century, paying particular attention to the complex interweaving of concerns both religious and political from the Mughal state through the newly independent Indian nation. Chapter one, “The Bhakti Movement and Its Discontents,” examines in detail the renowned Sanskritist V. Raghavan and his 1964 Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel Memorial Lectures delivered in New Delhi, the “high point in twentieth-century articulations of the bhakti movement idea” (29). Raghavan’s “wide-tent vision” of the bhakti movement (25) included not only Hindus but all of India’s religious minority communities in a sweeping movement from the fifth-century ce south, up the western coast, across to Krishna’s sacred land of Brindavan, further east to Bengal, and down the eastern coast to the south once again (see maps, 21–22). This narrative of bhakti as a movement dominated Indian textbooks, the national imagination, and scholarly discourse, at least until the violence of 1992, when Hindu nationalists tore down a mosque in the north Indian town of Ayodhya, and so tried to “pry apart Muslim and Hindu sides of the story” (285).

A Storm of Songs

Chapter two, “The Transit of Bhakti,” begins the lengthy examination of the late medieval/early modern roots of bhakti as āndolan, or movement, that constitutes the bulk of the volume. Front and center in this particular section is the celebrated passage from the Bhāgavata Māhātmya—known to every Indian citizen and scholar of Indian religious history as the centerpiece of the bhakti-as-movement narrative—where Bhakti personified speaks herself: “I was born in Dravida, / grew mature in Karnataka, / Went here and there in Maharashtra, / then in Gujarat became old and worn. . . . / But on reaching Brindavan I was renewed, . . .” (58).

Arguing that the Māhātmya is itself a northern text looking southward (to Dravida, or “southern” country) for legitimacy (69), Hawley then turns in the next chapter, “The Four Sampradāys and the Commonwealth of Love,” to consider the emergence of another critical organizing rubric alongside the Māhātmya‘s vision of Bhakti-on-the-move: the four sampradāys, or traditions of teaching and reception, all of them Vaiṣṇava (related to the worship of Viṣṇu) and all with roots variously located in the deep south, first clearly expressed in the late sixteenth- or early seventeenth-century hagiography of Nābhādās, the Bhaktamāl. Hawley attends carefully to the close alliance between the religious institutions at Galtā (in Rajas-than, where Nābhādās presumably wrote the Bhaktamāl) and the Kachvaha court at Āmer (112). Priyādās’s commentary on the Bhaktamāl in particular perpetuates the notion of the four sampradāys as an organizing principle for bhakti rooted in the south and spread across the north (146–147), although Hawley is clear that “the idea of the four sampradāys, capacious as it is, fails to take in the full web of connective bhakti tissue that was actually being assembled in north India in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries” (127).

In “The View from Brindavan,” Hawley considers the significant early modern developments at Brindavan, the constructed homeland of Krishna, through the cosmopolitan interventions of Kachvaha rulers, Mughal kings and ministers, and a variety of teachers from more southern locations. Also of note here are the competitive interactions of two rival sectarian Vaiṣṇava groups, the Gauḍīyas (followers of Caitanya) and the Vallabhites (followers of Vallabha), and the historical processes by which both communities formulated identities in the generations following the death of their respective teachers.

Chapter five, “Victory in the Cities of Victory,” strikes me as the real core of the book, arguing that a “trio of expressions of imperial power—Vijayanagara with its Seluva rulers, Brindavan with it Mughal-Kachvaha patrons, and the distinct Kachvaha domain at Jaipur . . . worked in different ways to take the idea of the four sampradāys to a new level of cogency and influence” (190–191). In other words, the wedding of bhakti as a coherent religious movement to the political ambitions of a nascent nationalism in the early twentieth century clearly had its precedents. In eighteenth-century Jaipur, for example, the ruler, Jaisingh II, “lent the considerable force of state sponsorship and state censorship to the notion that the historical movement of bhakti had been channeled in clearly identifiable institutional forms, all of them Vaishnava. . . . It played a part in Jaisingh’s remarkable effort to align his practice of kingship with Vedic ideals . . .” (196). Yet, unlike the Hindu nationalist narratives that yielded the violence of 1992 and the riots in Gujarat of 2002, it was the “Mughal ecumene [that] made it possible for the bhaktamāl genre, where the idea of the four sampradāys first emerged and where there was an explicit sense of a shared bhakti tradition, to bleed over into the world of the takirā, the principal Persian genre of poetic memory” (225). The colonial inheritance of this early modern political nurturance of bhaktias a movement and of the four sampradāys comes into clearer focus again in chapter six, where Hawley returns to Hazariprasad Dvivedi (first introduced in chapter one), another key figure in the making of the modern notion of the four sampradāys (230–234). He follows this with attention to Rabindranath Tagore and the circle of intellectuals at Shantiniketan University (235–245) and to other Bengali intellectuals, including Kshitimohan Sen (245–267), as well as to the murals depicting medieval saints on the walls of Shantiniketan’s Hindi Bhavan (275–284).

Hawley’s final chapter, “What Should the Bhakti Movement Be?” returns to questions first raised in the opening pages, and to significant problems so seldom addressed head-on in the analysis of critical categories in the study of South Asian religions: “Does an awareness of the historical contingencies that have produced the idea of the bhakti movement mean we have to consign it to the dustbins of history, or can we take that very historical embeddedness as a sign that this is a concept worth saving?” (12). Having examined in detail the historical processes by which “a master narrative of India’s religious past emerged” (295)—processes extending from the Bhāgavata Māhātmya and the Bhaktamāl through the Kachvaha court, the Mughal state, and the nationalist aspirations of Tagore and Indira Gandhi—Hawley suggests that the notion of a bhakti “network” (296 and following) might be more fruitfully productive than bhaktias āndolan, or movement. While he admits that “network” captures something of a “crazy quilt” (310), he hopefully suggests that “a far-reaching bhakti network as an alternative” to the idea of a movement perhaps liberates the study of bhakti from nationalist narratives and political ambitions, as it cannot do “the historical heavy lifting that the idea of the bhakti movement was intended to perform” (312).

A Storm of Songs presents the complex and contingent history of an idea so naturalized, so taken for granted over the past half-century or so, that it has until now wholly avoided the critical analysis ushered in by the first publication of Edward Said’s Orientalism in 1978 (as Hawley notes on pages 32–36, Krishna Sharma’s 1987 Bhakti and the Bhakti Movement is an exception). In laying out so clearly the processes that generated the four sampradāys and the notion of bhakti as movement, Hawley sets a new and very high standard for such critical scholarship. The scope—in terms of languages, histories, geographies, and subjects—is masterfully sweeping, as is the nuanced treatment of religious concerns in relation to political ambitions and contexts. Hawley resists making an easy generic critique of colonial European constructions or Indian intellectual collaborators. Instead, he artfully weaves a narrative extending back to the late sixteenth century, naming specific agents, locations, and religio-political circumstances generative of particular ideas and iterations, from Nābhādās and his commentator to Jaisingh II, Grierson (the British linguist), Tagore, Dvivedi, and Raghavan. As Hawley himself puts it, “India, Indians, and Indian languages turn out to be at least as important as England, Englishmen, and English in the generation, maintenance, and marketing of this major idea of cultural and religious history” (58). In such a context, the advent of European colonial rule seems less a sharp cultural break than an occasion for realigning older ideas with newly articulated ends.

One of the most refreshing elements of Hawley’s analysis lies in his attentiveness to the inclusions and exclusions of bhakti as a movement, pointing out on his final page that “the idea of the bhakti movement carries a message of simultaneous acclaim and subjugation,” one that initially endeavored to include all religious communities and regions of the new nation but that also “proved to have a smothering aspect too, one that many southerners and Dalits and Muslims have reframed or rejected” (341). Through A Storm of Songs, one comes to see clearly the work that the bhakti-as-movement idea has done, and continues to do, in history.

My scholarly work lies in the Tamil-speaking region of southeastern India—where the graffiti slogan “Hindi never, English ever” is often seen scrawled on walls and sidewalks, where the Hindi-language narratives of bhaktiāndolan are accorded no proper place in government schools or university curricula, and where mention of the four Vaiṣṇava sampradāys is most likely to elicit “a blank expression” (116). A Storm of Songs analyzes a narrative that has come to dominate Hindi-language materials not in wide circulation in Tamilnadu, one in which “the south was an ideal . . . an imagined entity, far more a mirror than a quarry” (228). Yet, despite its geographic and linguistic specificity, Hawley’s compelling work demands that similar questions be raised concerning all narratives of bhakti (as “movements” or otherwise) and the work that they do for regional and national identities. One measure of the success of Hawley’s book is the sheer number of questions and productive avenues for future research it raises for a scholar whose Hindi is entirely limited to āp kaise haiṅ (“How are you?”).

Despite the now voluminous scholarship on South Indian, Tamil-speaking bhakti, the kind of critical analysis that Hawley offers here has never been applied to the southern variations on the narrative, all with equally deep historical roots. First, one might consider carefully the terms—like Hindi āndolan—used in colonial and postcolonial scholarship to describe the rise of bhakti in the seventh through ninth centuries in the Tamil-speaking south. What terms were used in Tamil, and with what range of connotations? Who were the primary colonial architects of bhakti-as-movement narratives, and on what historical resources did they primarily draw? Who is included in the rise of Tamil bhakti, and which religious communities, institutions, and agents are excluded? How have monastic institutions in the region contributed to this narrative? What was going on in the Tamil region regarding bhakti in the early modern period so central to A Storm of Songs?

Hawley’s A Storm of Songs, in short, marks a major intervention, long overdue, in the study of South Asian religions that will no doubt generate lively discussion and new research projects for many years to come.

Anne Monius is Professor of South Asian Religions at HDS and author of the book Imagining a Place for Buddhism: Literary Culture and Religious Community in Tamil-Speaking South India.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.