Dialogue

Beyond Vengeance

Human rights are best fulfilled by building legal infrastructure.

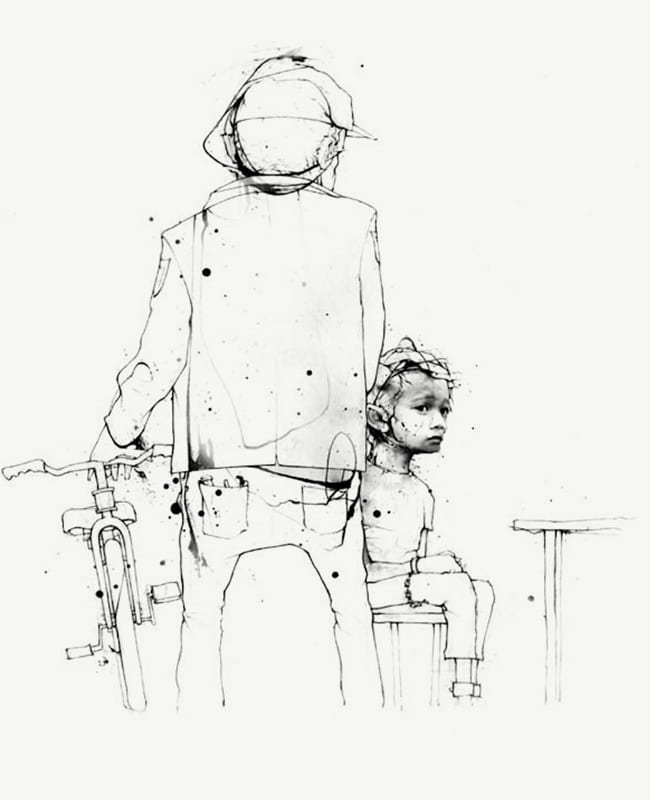

Illustration by Andrew Zbihlyj

By Karen Tse

About 25 years ago, when I graduated from college, I heard about the death squads in El Salvador and Guatemala, Ferdinand Marcos in the Philippines, and just terrifying stories about life in the hands of dictatorships, authoritarian and closed government regimes throughout the world. I remember thinking: “My gosh, this is terrible. What can I do?” All this suffering, torture, and death, and all I could do at that time was to write a few letters on behalf of political prisoners to Amnesty International and other groups.

Ten years later, as an attorney working for the U.N. Center for Human Rights in Cambodia, I walked into a Cambodian prison and came face to face with a 12-year-old boy who had been tortured and denied access to counsel simply because he had stolen a bicycle. As I looked into his frightened eyes, I realized that no one would ever write a letter for this helpless boy. At another prison in Cambodia, I met mothers who said that they had been there for more than a decade, for crimes their husbands had committed—husbands who had fled and could not be found. These were not important political prisoners; these were citizens who had become prisoners of the system.

The great irony of situations such as those of the Cambodian prisoners is: like thousands of people in this world who are tortured everyday, they were people that their government doesn’t really care about. The government might say, “Yes, we are focused on our political prisoners. Don’t touch those 5 percent. But you want to help a 12-year-old boy? Go right ahead.”

Lacking legal infrastructure and resources, few human rights laws are actually implemented in many countries, leaving their citizens particularly vulnerable to abuse.

We have an immediate and urgent opportunity to act. Twenty-five years ago there might have been precious little we could do to help those who might be tortured. But today those dictatorships, authoritarian and closed government systems have become emerging democracies and more open communist systems with laws designed to protect their people. Of the 113 developing, transitional, post-conflict countries that torture, 93 of these countries have all passed laws on the books that say that individuals have the right to a lawyer, and a right not to be tortured. But little of the dream is realized. Lacking legal infrastructure and resources, few of these laws are actually implemented, leaving their citizens particularly vulnerable to abuse. The ghosts of the past remain as vestiges of old systems despite new laws.

I believe that a lot of work that our human rights community does is overly weighted to-ward vengeance. We have an opportunity to move beyond punitive measures and instead actively support countries in the implementation of their own domestic laws consistent with human rights. While I fully agree that we must reconcile with the past in order to build an ethical future, this must be balanced with the need to work side by side with those in the country to build the legal infrastructure to protect today’s citizens from current abuse and torture. In Cambodia, $56 million is going into prosecuting 10 members of the Khmer Rouge. Over the last decade, courageous defenders have established the first 10 legal aid centers in 10 of Cambodia’s 24 provinces. In these 10 provinces, torture has been dramatically reduced by the presence of defense lawyers. For $200,000 we could build legal aid centers in the remaining provinces that have none. Unfortunately, the slow goal of building legal aid centers is not sexy to the international community.

Helping to fulfill basic rights on a daily level, implementing laws that are already on the books, such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which says anyone has the right not to be tortured and has the right to a lawyer—this is how we can work side by side with the communities of those being tortured—helping in the spaces in between and building structural and generational changes.

Torture, as people most often see it, is a political issue; and it is, for about 5 percent of the people being tortured in this world. But for the other 95 percent of the people being tortured around the world, they are being tortured because it is the cheapest form of investigation. In these countries, torture has become an economic resource issue, but the human rights community is often told that it will be impossible to work with these governments. In our work in countries including China, Vietnam, Cambodia, Burundi, Rwanda, Zimbabwe and India, I haven’t found this to be true. And I believe we can hold fast to the hope for at least the remaining 93 countries as well.

When I first visited Cambodia, in 1994, there were fewer than 10 attorneys who had survived the Khmer Rouge. Within just a few years, however, people started to shift their consciousness in regard to torture confessions. By working with countries such as Cambodia, helping them implement their own domestic laws in a way that is consistent with human rights, we can help reduce the number of torture victims.

Volunteering at an orphanage in Cambodia once, I spoke with a woman named Sister Rose, a missionary of charity who has no law background. I said, “Okay, what would you suggest I do for human rights?” And Sister Rose answered: “It’s very easy. There is only one thing you need to remember. You should look for the Christ or the Buddha in each person.”

Karen Tse, who received a master of divinity degree from HDS in 2000, is a former public defender and founder of International Bridges to Justice. She was recently named by U.S. News and World Report as one of “America’s Best Leaders.” These words are adapted from a talk presented at the “Reporting Global Conflict” conference, which was sponsored by the Nieman Foundation for Journalism, with HDS, held on May 9-10, 2008.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.